Zen…in cc’s

I want to be fully transparent concerning the subject matter and inspiration for this blog. The title above comes from this precious work of fiction:

Pirsig’s book was published in 1974 and I read it – digested it – the following year. A concise description of the book’s content and focus of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance can be found at the online encyclopedia of information, Wikipedia at this link. The lure to me at the time stemmed from my penchant for motorcycle riding combined with a passion for reading and a deep curiosity regarding such an intriguing title. In 1966, at 16 years of age, I purchased my first motorcycle, a black Yamaha 80cc very similar in style and structure to this photo of the bike model (not my actual bike):

The bike featured is 100 cc but the model is exactly like my 80cc and the closest image I can find of the model. My best friend’s brother sold me the bike when he upgraded to a 250cc – I think – twin carburetor, dual exhaust, a much more powerful machine. If I asked my father for permission to purchase it, I don’t remember. I do recall that, as a pilot, he regarded motorcycles as “two-wheeled kiddy-karts” without any apparent concerns for their safety or mine. In fact, at the time, licensing was a simple matter of paper-work application with the Ontario Ministry of Transportation (you only needed a beginner’s permit – G1 now, I think – to drive a bike); insurance on bikes was very cheap; there was no rider-training required for owners; and most stunning of all, helmets were not mandatory in our province until the summer of 1967. In the latter regard, although I owned a white, sort of bucket-style helmet, I only wore it for highway driving before ’67, never for in-city commuting which comprised 95% of my bike use.

My fascination with and love for riding my Yamaha were very deep. I parked it at the side of our duplex at 730 Sevilla Park Place, London, and covered the machine with form-fitting tarp at night (no garage). For almost 3 years, it remained my main mode of transport – most certainly my preferred means of driving. Mostly, in grades 12 and 13, I drove it forth-and-back to my high school, Beck Collegiate, perhaps a 5 km, one-way commute via backstreets from the south to the east parts of the city. Once at the school, there was a designated parking spot for bikes – though not many students owned motorcycles – at the northwest side of the building near the playing fields. I wore a sort of oil-skinned rain coat for wet and cold weather protection though I vividly recollect arriving home or school with soaked shoes and pants. And I remember insurance covered bikes from May 1st to October 31st, regardless of weather; driving outside those dates was not permitted and everyone just seemed to comply. Certainly, as the son of a then insurance salesman, I was aware of the law and lack of coverage should an accident happen in the non-covered 6 months of each year.

I learned my riding skills and respect for my own vulnerability as a bike rider from my friend’s brother; Gary took me for riding lessons when I bought the bike from him, carefully instructing me how to ‘steer and weight and lean’ the bike from my hips. The handlebars literally turned the vehicle but balance and control came from subtle centre-of-gravity shifts at the hips. It is an indescribable feel of and for the bike when I learned the subtleties of hip control. I could sway the bike ever so slightly right and left while moving in a straight line. When making turns, riders always lean into the turning direction with your whole torso, something it often took considerable effort to teach first-time passengers. I was never into trail bike riding; for city road driving, I was taught never to take my foot off the toe support when leaning into a turn. Should that foot touch the pavement and any torque be applied at foot placement, the results could be broken bones. One of my colleague’s sons had to have his lower leg amputated because his foot and leg were so mangled from using his foot as a turning pivot and losing control of his bike. By far the Number One lesson I retained throughout my almost 50 years of motorcycle-riding is summed up in 3 words, trust no one. When that advice was shared with me, it felt on the surface as though it were such a negative way of thinking while enjoying the feeling of unfettered freedom that bike-riding engendered for me. And yet what it came to mean as a perpetual defensive driving mantra was, for example, looking in all directions at 2-way, 4-way, traffic light stops/intersections. Even with the right-of-way or green light in my favour, what if one car missed the stop sign or ran a red light with me in the intersection? If that accident were to happen, I might be the most mangled or dead person who was ‘in the right’ or not at fault. In the same vein, it became so habitual to check my side-view mirrors constantly and always to look behind me, not merely in the mirror, when changing lanes.

When riding, I was so aware of anticipating what was happening 4 or 5 or more car-lengths ahead of me, mindful, almost peripherally, of the vehicle and its behaviour immediately ahead of me. I was constantly panning my driving horizon, subconsciously collecting and sorting traffic information. Bikes, even small ones like my 80cc can accelerate very quickly; stopping, using both the handlebar, front wheel hand-brake and the foot-pedal rear brake worked well and needed lots of lead-time to reduce speed or stop when required. For decelerating with lots of lead-time, I often down-shifted, gradually going from higher to lower gears to let the engine do the work of braking the bike. Rain, leaves in autumn-riding, oil- and mud-slicks were all enemies of stopping. Only twice in all my years of riding different bikes did I have to “put the bike down.” That expression and its meaning were taught to me when I first learned to ride but it’s not a skill easily practised. It refers to the split-second decision a bike rider makes when s/he realizes it will be impossible to stop the motorcycle in time to avoid a collision.

It happened to me within a year of owning my first bike. I was riding on highway # 3, coming from Simcoe, Ontario into Delhi in light-rain conditions, mid- or late-July, very light traffic flow. It was dusk and as I entered the little, tobacco-industry-dominated town of Delhi, reducing my speed, the transport truck in front of me either swerved and/or applied the brakes very suddenly. It was two-lanes coming into Delhi and my reaction was to change lanes while gently applying both brakes; however, there was a vehicle in the other lane. With what seemed like no other thought, I applied my front brake and used my hips to bring the back end of the bike around to my side until it was perpendicular to my direction of travel. At the same time as the back pivoted, I over-leaned away from the direction of travel to let the whole bike land on its side while I simultaneously let go of the handlebars and foot-rests to land and slide on my left side on the road while the bike skidded toward the truck. It all happened in an instant. Luckily, there was no vehicle behind me or if there were, it managed to circumvent me and the bike; neither I or the bike came close to hitting the truck. My sense was I would not have been able to brake well enough to avoid collision and in putting the bike down at this relatively slow speed – maybe 15 miles per hour (we hadn’t converted to metric in 1967) – the only impact on me was mild shock and a slightly-torn sleeve at the shoulder of my rain jacket. My Yamaha, I later discovered, had one small scratch on each of the tool-pouch cover and gas tank; however, the immediate bike issue was a bent and mangled, unusable gear-shift handle, very likely the point of impact when the bike landed on the pavement. The latter issue seemed to occupy my thoughts – repair with a new handle was essential but how would I get to the only bike shop I knew, in Simcoe about 10 km distant? Turns out, I was able to use two fingers to pull the little metal tab on the end of the wire normally attached to the clutch-engaging-handle. There were no stoplights or stop signs until I got back into Simcoe so once the bike was in highway gear, I didn’t have to shift gears very much.

As I think back on it, the whole incident seemed so surreal – axiomatic in my mind and body. It didn’t deter me in any way from riding; instead, it seemed to confirm my bike-acquired slogan, trust no one. It was as though learning to ride the motorcycle safely and skilfully grounded me such that I was able to delight in the sheer joy of riding. Like most things in life that have brought me enjoyment, motorcycle riding just is, now was, fun. Odd as it may seem, I always felt very earth-bound, connected to the pavement beneath my wheels, my feet mere inches from that surface. I remember watching the Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper 1969 now-classic, if not iconic movie, Easy Rider. In the film, Wyatt and Billy, their personae, travel across the US astride their “choppers,” extended handlebars and all, in a kind of counterculture, spiritual quest…

Dennis Hopper is on the left, Peter Fonda on the right. As I recall, they did their own riding.

What attracted and continues to attract me to the movie is the titular adjective, “Easy.” It is the perfect, bike-riding/feeling descriptor. Riding feels in flow, in sync, just so easy. Though always so mindful of my environment and traffic, I was so aware of the freedom of riding and that feeling, to me, oozed from the cinematic screen in the bike scenes from Easy Rider. Shifting gears with left hand on the handlebar handle, left foot on the clutch lever (1st gear, one push down, the other 4 gears required the top of my shoe-toe to pull back), foot and body so softly and deftly aware of whether I need to up- or down-shift. From a full stop, even the smallest of bikes, like my 80cc, have stunning pickup and accelerative potential and I confess to smiling often as I sped away from vehicles after a traffic stand-still. And, I cannot leave this section that began with the mention of Easy Rider without a visual and auditory reminder of its fabulous theme song, Steppenwolf’s Born to be Wild:

Of related interest to me is Neil Parry’s video rendition wherein he vocally and accurately mimics the manner in which motorcycles sound just like their brand names:

So priceless and precisely true! Makes me smile every time I watch this video and I’ve watched it a lot. Bikes, like most vehicles have exhaust baffles inside their mufflers. Bikers, some of them at least, delight in taking out the baffle in order to accentuate the sound. I never did but the sound was loud and predictable, even in the putta-putta-putta vibration when idling, is distinctive and to some, annoying. My little Yamaha was a kick-start as opposed to key-in-the-ignition method. And there was something almost mystical for me in kick-starting the bike; in fact, people often watched as I did it. Always, once started, every bike rider has to rev the engine via the downward-rotating throttle on the right handlebar. Macho? Perhaps, and I read a statistic, that almost half of current new bike purchasers are female and they ‘throttle’ too.

As to literal motorcycle maintenance (ignoring for the moment, the Pirsig book title at the top of this blog) it was simple – at least, with my limited knowledge, I kept it simple. Not once did I take my bike to a store for maintenance and I knew exactly nothing about engines, motorcycle or otherwise. Uncharacteristically, I read the 80cc manual cover-to-cover and followed its prescriptions for maintenance quasi-religiously. I kept the oil topped up, checking it regularly, along with tire pressure although the latter seldom varied. At the base of the gas tank was a fuel valve (petcock, I think it is called). The manual said to turn the valve to off when finished riding for the day. Not sure why, but I did that every day. The best feature was a third setting on the petcock – after Open and Closed was Reserve. With no gas gauge on my bike, I could only approximate when I would run out of gas. Gas was cheap then and motorcycles use so little gas relative to larger vehicles. Gradually, I learned to remember how many city miles I could get between fill-ups. However, the beauty was this: if the tank emptied while riding, the bike would sputter audibly and decelerate. Recognized quickly, all one had to do was reach down to the valve and turn it to Reserve. I don’t remember how many miles that gave me but I was usually diligent in stopping to get gas as soon as I could once on reserve. I only had to remember to turn the valve back to Open after refuelling or risk the tank going right to empty if I were to ride it long enough and forget to re-set the valve.

My bike came with a sparse tool-kit, its pouch accessible with the handle-bar lock key (critical to prevent theft) inside a little triangular-shaped compartment under the left side of the seat. Regularly, I changed the spark plug having to first learn how to set the gap on the end of the plug for smooth engine-running. Tightening and oiling the chain was equally simple – I think I even put graphite on the chain once. Both the front wheel brake and back wheel brake were easy to adjust; from constant use, I knew when calibration was needed. The only maintenance hassle I remember was the necessity in the colder Spring and Fall weather to uninstall the battery located, without easy access, underneath the seat (about 4 inches square by 6 or 7 inches long, it required very occasional topping up with distilled water), and bring the battery into the house overnight. Not doing so usually meant not being able to start the bike. I didn’t have a battery-tender, just kept the battery at room temperature warmth near the back door to install just before I next rode the bike. If I forgot to bring in the battery, I learned that I could put the bike in first gear, hold in the gear-shift handle, then run awkwardly along beside the bike, both hands on the handlebars and when some speed was achieved, jump astride the bike at the same time as popping the gear-shift handle and it would kind of jump-start the bike. Very likely, the feat was amusing to watch; for me, it was just part of the ‘zen’ of motorcycle riding. Except for washing my motorcycle – something I loved doing, keeping it both clean and shiny – that was the extent of sustaining my Yamaha’s functional, ride-ready state.

The Yamaha 80 was too small for carrying a passenger, just weighted and slowed down the bike. I do distinctly recall the first person I ever took as a passenger – my younger sister, Marnie. She was terrified but I cajoled her into it and said I promised it would just be a short ride down to the end of our street and back; if she liked it, we could go farther. Sadly, I elected to turn around in a gravel driveway, completely unaccustomed to balancing the bike with a passenger. Too late or not with enough support, as we stopped, I delayed putting my foot down on the gravel and the bike slid out from under us, Marnie landing unceremoniously on the gravel. Uninjured, she was very angry, rightly so, and elected to walk back to our house. I felt awful for a long time and did apologize profusely; she never asked to ride with me again.

During my last summers working in tobacco harvest, my bike was my main mode of transportation from my grandmother’s apartment in Simcoe to the various farms where I worked. While I didn’t relish it, I had no qualms driving my bike on highway 401. By far my most adventurous and, in retrospect, probably dangerous and foolish trip on the bike was travelling from London to Sault Ste Marie via mostly Michigan highways. I had no idea if gas stations were open late, so I carried two quarts of gas in a gym bag perched across my thighs – that too, not the wisest strategy. I drove two-lane highways for the first half of the trip and thought all was going well until I was pulled over somewhere near Port Sanilac by a state trooper shortly after crossing the Canada/US border at Sarnia/Port Huron. It was dusk and the officer explained to me, shaking as I was with fear that I had committed some heinous crime, that my tail light was not working and he could only discern my front headlamp shining on the road and didn’t know what vehicle I was. Very kindly, he escorted me a few miles to a garage where I purchased a $2.29 light bulb and was back on my way. The whole trip took me 11 hours, the last 6 of which were done on Interstate 75 from Saginaw to the Upper Peninsula. The speed limit was 70 or 75 mph at the time; top end on my Yamaha was 47 mph, just 2 clicks over the minimum posted speed of 45. Driving over the unanticipated expansion joints of the Macinac bridge was terrifying.

My Yamaha 80 was such a thrill to ride, even a kind of companion to me – it was mine alone; it demanded respect and care; it offered a freedom in transportation; and it required physical, almost athletic skill to ride safely. I owned quite a few motorcycles over my decades of riding. The one I think I liked the most was a Yamaha 500 cc, like this one:

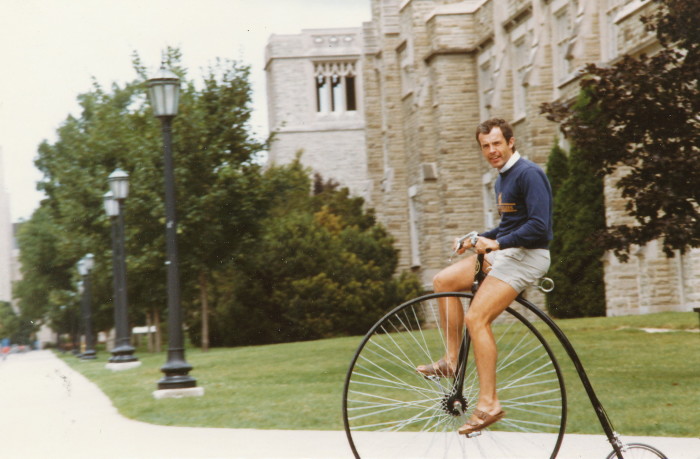

Mine was scarlet-red and purchased sometime around 1984 after nearly a decade of riding my 3-speed bicycle to work 12 months of the year. I’m not sure what it was about the 500 but it just felt comfortable. I remember taking each of my 3 sons riding on it over the years, seating them, one at a time, in front of me for what I felt was greater safety. The most unique ‘bike’ I ever owned was this Rideable Replica penny-farthing bicycle, purchased and shipped from Oakland, California in 1985:

Me demonstrating how to ride the farthing around the traffic circle near Thames Hall at Western

The farthing was an exact replica from those produced and ridden in the mid 1880s. Made of steel or metal tubing, with wheels of solid rubber, the rider was seated about 4 feet off the ground. There was a brake lever that compressed rubber pads to the diminutive rear wheel but it did little more than provide psychological comfort, virtually no contribution to slowing the vehicle. Riding it was easy; getting on and off it was the challenge. A little metal foot bar was located just above the back wheel on the main frame; with left foot on the bar and both hands on the handlebars, one kind of scooted the farthing with the right foot and once enough momentum was achieved, you stepped up and swung your right leg over the seat and then tried to catch the front wheel pedals that were already in motion, direct-drive like tricycle pedals. Getting off was the real skill. I had to time one pedal at the top of its arc, swing the other leg over the seat and as the pedal moved toward the ground, hop off the bike all the while holding the handlebars. The evolution of the bicycle had a tremendous impact on transportation, sport, and women’s fashion. Thus teaching sport history students seemed more alive if they could experience the farthing. Below is a student’s video of me teaching them to ride the bike in Thames Hall gymnasium around 2006:

The video doesn’t show the dismount but the art of getting on it and the ease of riding are readily apparent. Students loved riding the farthing although I was careful to have them sign a waiver before trying it out. We found that anyone under 5 feet 3 inches in height, had to push the pedals with alternate feet because their legs were too short for continuous pedal-motion. I rode the farthing in a few Santa Claus parades – pre-COVID-19 days – and even drove it to/from the university. However, the reaction of people on the streets was one of two extremes – they either ignored it, seemingly because they just weren’t sure what it was, or, they were so fascinated by it, they wanted me to stop and chat. Sometimes, car drivers, in the latter camp of enthrall, inadvertently steered toward me. I decided commuting was not very safe.

My last motorcycle was this Honda Shadow Spirit 750 cc that I bought for $2600 in 2006:

I had pretty much given up on riding motorcycles and sold my then last one in the late 1990s. But I missed the zen feel, that sense of calm attentiveness and ease, a place where my actions and decisions seemed more guided by intuition than conscious effort. Shadow: I think more than anything, it was the word itself – ‘shadow’ – that attracted me to purchase this specific vehicle. The word had psychological connotations and I had done a lot of work around the shadow aspect of my own being (one writer described the shadow or darker aspect of our persona as “the long bag we drag behind us“). My wife, Jen, was sort of peripherally involved in my decision-making process in that I had introduced her to the idea when we had been fortunate to inherit some money. I confess I took liberties with her listening to the concept. She was away for a few days during which time I bought the bike and had flowers of gratitude awaiting her arrival home coincident with the bike’s ensconcement in our garage. Graciously, she accepted my desire and need for the motorcycle. I was quick to point out I had also purchased 2, metal-padded motorcycle-specific riding jackets and promised to wear steel-toed shoes whenever I rode it, and most of all, to adhere to my learned dictum, trust no one.

And what a magnificent machine it was, so far removed from my Yamaha 80 with its electric start, gas gauge, oil indicator, windshield, and hard bags (visible over the back wheel in the image above) in which I could carry almost anything. The low-slung seat felt like I was closer to the ground than any other bike I’d driven and almost embedded in the vehicle. I distinctly recall picking up the brand new bike from Inglis Cycles in late Fall. It had been some years since I had driven a bike and I was a bit nervous. I rode it up and down the street in front of the Inglis store until I got the familiar in-my-bones feel of the bike. I rode it home beaming with excitement with just very light traces of snow in the air, but not on the roads. For 10 years, I rode and cherished that motorcycle, mostly to and from Western. Parking on campus for bikes meant you could park adjacent to almost any building. A few years after I had the bike and had moved my office to the new Health Sciences’ building, some of my friends with whom I play hockey weekly, decided that the concrete island on which I parked my motorcycle should be signified. For many years, ‘The Island of Dr Morrow,’ a quip on the H.G. Wells’ science fiction novel and companion film – The Island of Dr. Moreau – graced the bumper post on my parking island:

I arrive back to where I began this blog, at Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and my attempt to convey what motorcycle riding meant to me in my life. In 2016, just after my rotator cuff repair surgery to my right shoulder, I made the decision to sell my Shadow. It hurt, broke my heart ever so slightly (always loved and believed in Carly Simon’s vocal line, “there’s more room in a broken heart”). I felt that I might not be able to make the split-second decision to put the bike down out of unconscious desire to protect my healed shoulder. I would not ride with ease but in fear and that familiar riding ecstacy would evaporate. Thus, it seemed to me, my motorcycle “maintenance” was directly related to 50 years of ease and passionate riding; better it was, I felt and still feel, to maintain myself – trust no one came full circle to mean trust my intuition. There are many, many things I remember from Pirsig’s book and his ambitious subtitle, An Inquiry into Values. I think in 1974 when I first read the work, it was my initial exposure to just how significant values are in my life, our lives. They guide us, serve us as ‘north stars’ of what is right, true for each of us, and help us know what we feel. Of all the quotations I could recite from the book, this one speaks volumes to me in concert with what I learned from and about riding my motorcycles: “First you get the feeling, then you figure out why.” For me, the “cc’s” (cubic capacities) or engine level of power was never the why. And I have traded one ‘zen’ for another ‘zen:’

Regarding the motorcycle Zen book and the quotation above, I felt why and tumble home to my memories of motorcycle maintenance, and what I valued, inexpressible in many respects, from my decades of bike riding.