Tramps

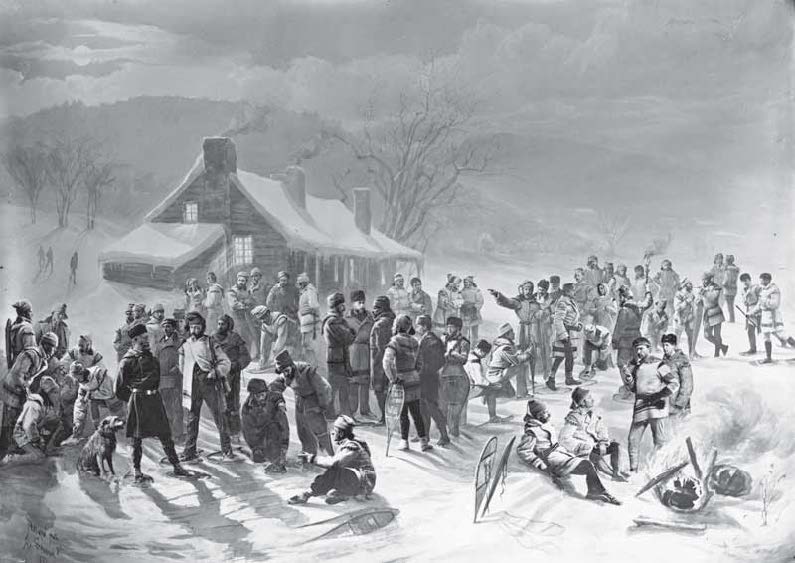

Softly, silently, like the snow flakes upon which they trod, with the peculiar roll of the shoulders and jogging of the hips went the band of athletes, the livid torches illuminating their picturesque costumes, their bright turbans, their fleecy bashilisks [coats], and their cerulean tuques. Tramp, tramp like the stroke of fate went their webbed foot-falls. ~ Montreal Gazette, 16 January 1873.

The idyllic, nocturnal snowshoeing picture above was duplicated and posted recently on Facebook as an indicator of a university professor’s notation to have his class study and discuss an article I wrote more than 30 years ago. As I start this blog, it’s early February, mid-winter 2021 – still shrouded in the Covid-19 pandemic – and I have been thinking about winter pastimes and following up on my desire to write less academically and more fluidly about narratives that interested me as an historian and continue to interest me for the richness of their meaning in lives lived in the past. Nineteenth century Montreal sport history was a passion for me and I remain especially fascinated by the pastime and sport of snowshoeing particularly as this activity manifested and grew in popularity within that city over a 50-year period. Montreal itself is a special city that exudes its history – the major metropolis of New France’s, British North America’s, and Canada’s vast and rich hinterland. I have spent many weeks and months in the city researching its sporting past and, whenever I could, taking my daily break to run the ‘snake’ or winding path, about 4 km, if my body-memory serves, twisting up to the cross atop Mount Royal and then back down to the Peel Street steps, my ascension point. As for snowshoeing, it was winter jollification relished just prior to team sports’ escalation in popularity. Note the almost reverent, pastoral characterization of the 1873 Gazette description under the picture title of the image above. This blog then represents my attempt to breathe reminiscent life into Montreal snowshoeing and snowshoers during the last half of the 19th century. While I utilize the article (linked in full above), the blog is much more informal and I hope more compelling to read and understand how this currently unheralded winter activity held such potent attraction over 100-150 years ago.

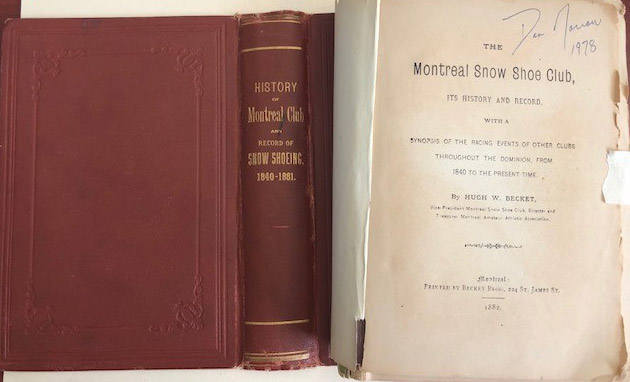

My primary or first-hand sources on Montreal snowshoeing come from a remarkably preserved set of documents on early sport clubs in Montreal, a fonds or collection that now resides in Canada’s national archives in Ottawa. I also utilized microfilm versions of civic newspapers and in particular, I relied on this little gem of a book…

Becket inscribed his book with these words: “to my comrades of the Montreal Snow Shoe Club, this work whose principal purpose is to relate the history of the old “Tuque Bleue,” is respectfully dedicated.” I found a copy of the 521-page tome gathering dust in an Ottawa second-hand bookstore in 1978. It remains a treasure-trove about early snowshoeing history. In fact, as of 2021, over 7,000 people viewed an online, pdf version of the book on a Pickafile website book-fileshare provider.

The origins of the snowshoe are very likely aboriginal and utilitarian – a means of winter transportation – although its country of origin is obscure but very likely somewhere in North America. Early ‘shoes’ must have been formed from hardwood, forged and bent into teardrop or beaver-tail shapes with the footing made with interlacing, woven leather or rawhide thongs and with similar material used to strap the devices to the feet. in the latter regard, it would be the toe that was bound to the snowshoe, leaving the heel free to lift as one would when walking normally not in snowshoes. My experience in trekking with modern snowshoes is that owing to the width of the shoe (the greater surface area of the stringing necessary to stay atop snow), initially at least, it feels like I imagine walking in a diaper must feel like – legs spread wider than ordinary walking, a bit clumsy and awkward compared to normal movement. Along with Native peoples, in New France and British North America, the fur traders – coureurs de bois and Nor’Westers – as well as military men and white men living/working in the bush must have found the snowshoe indispensable in winter months. There is no evidence of any widespread use of and/or sporting contests using snowshoes within urban areas prior to the 1840s; however, the absence of evidence is not necessarily the evidence of absence. It is easy to imagine hardy fur traders and Indigenous peoples having impromptu races and making boasts of prodigious distances travelled on snowshoes. One of my own beliefs about the origins of any sporting behaviour stems from a general principle of humankind’s impulse to play and the sporting corollary, ‘if it moves, why not race it.’

According to Becket’s account (in the book pictured and cited above), the earliest white ‘disciples’ of snowshoeing were drawn from relatively elite male members of Montreal society – men of privilege who likely took part in snowshoeing as much for the social, convivial aspects as for the athletic activity itself. Sometime around 1840, a group of 12 men ‘tramped’ regularly on Saturday afternoons and formally organized themselves into the Montreal Snow Shoe Club (MSSC) three years later. The word ‘tramp,’ as it quickly adhered to the snowshoeing fraternity, likely referred to the heavy, snow-crunching steps of the snowshoers. Tramp is wonderfully onomatopoeic in mimicking the sound of the leather-thong-woven devices impacting on fresh snow. And it seems to connote a continuous, deliberate tread of footfalls, even a march or trudge or walking excursion. The term is not only sound-expressive but carries a para-militaristic meaning in that tramps were conducted in a very orderly and disciplined fashion. Typically, snowshoers walked in single-file presumably for ease of movement as each ‘tramper’ used the packed snow of their companions and to set the pace for the tramp and for ease of movement on narrow trails as well as for using each person in front of each other as a wind-break in extremely cold conditions (a practice still called drafting in longer foot races). Leading the tramp was the highest-ranking club officer, as in president, secretary-treasurer etc. The last person in the line was the ‘whipper-in,’ a hunting-derived term that came to mean the person who kept the pack of trampers together on excursions, a prestigious role usually given to the most experienced snowshoer on each tramp.

The MSSC was the leading club in the city. Owing to the distinctive blue tuques worn by its members, the MSSC became known as the Tuque Bleue; as other clubs formed, they adopted their own distinction by selecting their colour…Tuque Rouge, Tuque Verte, Tuque Brune and so forth. By mid-century, the early clubs selected a rendezvous or meeting time with the Tuque Bleue members resolved to ‘muster’ – another military connotation – twice weekly at Dolly’s Chop House. There were no indoor facilities for most clubs; thus the winter pastime necessitated precision of place and time to meet. . .

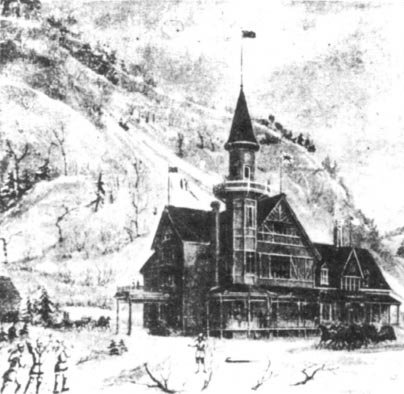

By the same token, the completion of a tramp was celebrated by a “repair” to a local tavern such as a famous café in St James Street wherein the snowshoers “stretched their pedal extremities under mine host Tetu’s mahogany” to consume food and drink. In later years, tramps either ended or were a halfway turning point at a club house in the Côte-Des-Neiges neighbourhood at the western side of Mount Royal: The Athletic Club House at Côte des Neiges on Mount Royal. This club house served as snowshoers’ social centre during the 1870s and 1880s. Some of the early images of snowshoeing were engravings, not camera pictures, hence the grainy quality of these images.

The Athletic Club House at Côte des Neiges on Mount Royal. This club house served as snowshoers’ social centre during the 1870s and 1880s. Some of the early images of snowshoeing were engravings, not camera pictures, hence the grainy quality of these images.

Treks or tramps often took place along the still-extant, winding trails of Mount Royal; therefore a meeting place on the mountain was appropriate. While eating and drinking were common so too was singing exemplified in the reflected glorious words and ‘manly’ incantations of this song penned in 1858:

Song of the Montreal Snow Shoe Club

By George Parys

Pass the bottle and fill your glasses,

Now that each has munched his “grub”,

We’ll drink success to the pretty lasses,

Whose lovers belong to the Snow Shoe Club.

Yes, to-night we’ll all unite

To drink success to the Snow Shoe Club.

At racing, we challenge all creation,

Let them be prepared for a very hard rub,

If among the picked men of any nation,

Some think they can beat the Snow Shoe Club.

Then to-night, with all our might,

We’ll drink success to the Snow Shoe Club.

All pretty girls take my advice,

On some vain fop don’t waste your “lub”,

But if you wish to hug something nice,

Why marry a boy of the Snow Shoe Club.

Then each night, with wild delight,

You’ll sing success to the Snow Shoe Club

~ Becket, MSSC History, pp. 44-45

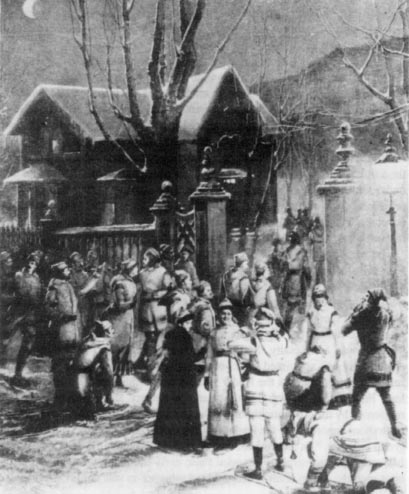

Gallant? Certainly suggestive – even sexist by contemporary standards – and boastful. From best evidence, women did not snowshoe until later in the century. Any descriptions, images, or sketches of women snowshoeing were quite passive, romanticizing both the landscape and their male counterparts as in this 1881 image:

Moonlight Tramp with the Snowshoe Club, Canadian Illustrated News 26 March 1881

On tramp evenings or afternoons, older club members would attend the social gatherings on the mountain and elsewhere by taking a sleigh conveyance to the venue. With a tinge of disparagement, such persons were referred to in press reports as “driving members,” ostensibly not as deserving or at least to be distinguished from those who did snowshoe to the locations. Even eating was ennobled as this brief 21 January 1860 colourful culinary description exudes:

The necks of all the turkeys, geese and chickens in the village had been twisted for

the occasion and a sirloin of beef weighing 100 pounds lay smoking on the table to

which the hungry snowshoers did ample justice.

Intriguingly, from a modern perspective, dancing took place often at the taverns and clubs. “Ladies’ nights” at these mountain or inner city gatherings were only inaugurated in the mid-1880s and even then were annual in frequency. Thus, the exaltations of manliness, ironically now, encompassed the all-male conviviality, “a little terpsichorean [= related to dancing] exercise was indulged in, those representing the fair sex doffing their blanket coats.” Cotillions, a precursor to square dancing, were the most common forms of dances and most newspaper descriptions underscored the female-imitative behaviour.

For some 20+ years since the inception of the first snowshoeing club, long distance tramps were the de rigeur form of the sport. Some excursions were 20 km or more, testimonies to the aerobic, athletic prowess of the hibernal activity’s devotees. In the same vein, competitive tramping events – if it moves why not race it – were often conducted as steeplechases, fashioned after the same-named country-side horseracing events using church steeples as directional, navigational landmarks. By the late 1860s and 1870s, snowshoers were distinctive and immortalized in such Notman photos as the one at the start of this blog and more characteristically like the one below:

The Snowshoers’ Halt on Mount Royal 1889. Note the torches and distinctive blanket

coats. Source: Dominion Illustrated Monthly, 1889.

The Notman photographs are interesting in that they are all composite photographs. For example, in the ‘Halt’ above, there just wasn’t the technology at the time to take such a picture in daylight let alone at night. Instead, the treed, mountainous back-gound was painted (in oils, perhaps); each snowshoer was posed as he would appear in the final product and photographed individually in the Notman Studios. The negatives from those individual pictures were hand-cut by “miniature artists,” sometimes, for more expensive commissions, they were hand-painted as well. Then the image was affixed to the painted background until all photographs were in place, scaled, with back-lighting and shading touch-ups and then the whole picture was re-photographed as a ‘composite’ picture. The final image was preserved as glass or lantern [projection system at the time] slides copies of which could be purchased with the larger, full versions often being framed for display on the walls of individual clubs like the MAAA or put on display, as many have been, at the McCord Museum in Montreal. Perhaps too stylized or too stiff to be called works of art and yet each composite took hours and hours of studio posing time, background painting endeavours, and completion of the end product. At the very least, the Notman composites are proofs – photography pun intended – of the popularity of snowshoeing by its devotees. And if royalty could be included in the portraits, such as the one below with Lord Dufferin, Canada’s Governor General, bearded and sporting the most luminous white coat at the front and centre, it added considerable felt and portrayed refinement to the snowshoeing fraternity in an imperial country…

Montreal Snow Shoe Club, Mount Royal 1877 Notman image featuring Lord Dufferin

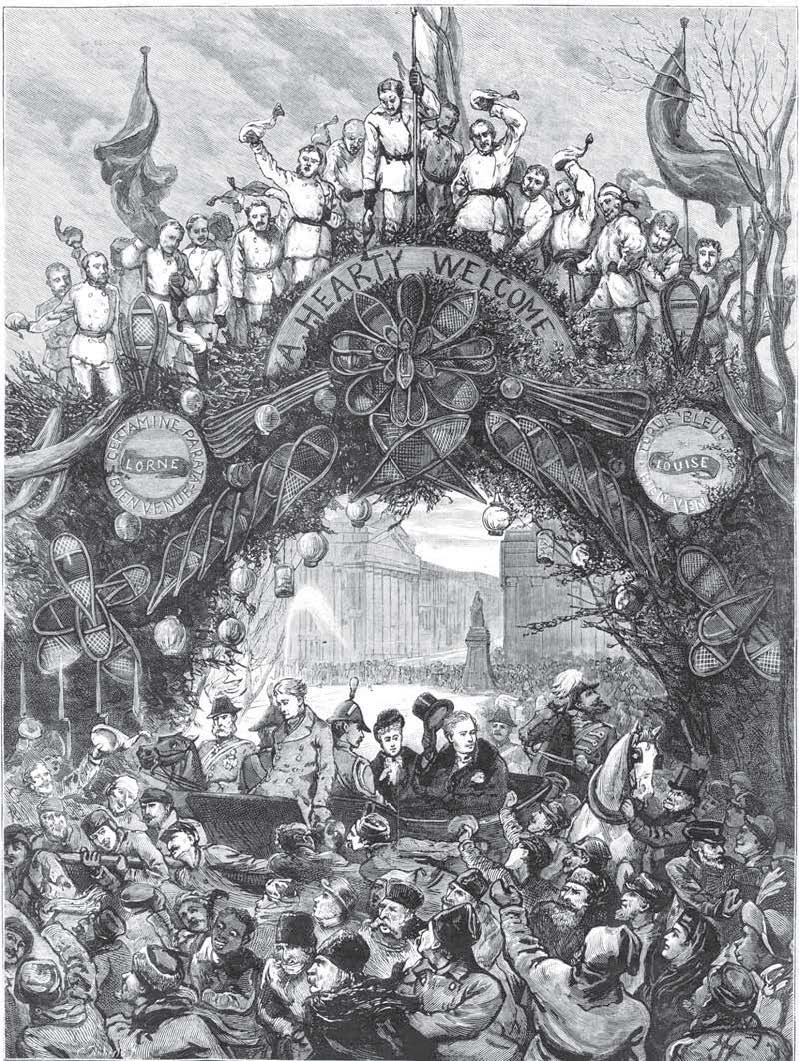

Prestige, politics, and patronage were all part of snowshoers’ perceived place of distinction in Montreal. When the newly-appointed governor-genearl of Canada, His Excellency the Marquis of Lorne and his wife, Her Royal Highness Princess Louise were paraded by royal carriage through downtown Montreal in November 1878, the MSSC built an elaborate arch for the occasion…

Such arches were not unique to the snowshoers for festive holiday parades or to welcome dignitaries. However, this 1878 arch is such puffery on the part of the MSSC. The arch was carefully constructed, festooned with green boughs, presumably invoking country evergreens on tramps, the centre arch buttressed by two towers with large welcoming decals atop each tower. A rosette of snowshoes can be seen top and centre, just below the words, “A Hearty Welcome” with dozens of snowshoes decorating the surface and the Union Jack and Red Ensign flags flew over the top. Unique in this street span was the posing of snowshoers atop the structure, clad in their blanket coats thereby creating a “living arch” cheering their welcome to the royal couple.

A special, celebratory and welcoming gesture inaugurated by the MSSC was “the bounce.” It was performed by a circle of snowshoers at the centre of which was a person lying prone across the linked arms of the men in the circle. At some signal the person – dignitary, new member, or race victor – was tossed in the air, caught, then repeated a few times while the men cheered. Below is a rather famous bounce depiction…

This Notman image was made in 1886; the person bounced is Lord Stanley of Preston, two years before he became governor general of Canada and 7 years before he bestowed his now-iconic hockey trophy, the Stanley Cup. The illustration underscores the snowshoers’ characteristic, adopted uniform, a white blanket-coat tied with a club-colour sash around the waist, with leggings, moccasins, and tuque all in matching club-colours. Even the epaulets – more militarism – often sewn on the coat shoulders were club-coloured. A more distinctive picture of the uniform and the nature of the snowshoes is this one taken in 1881…

George Beers, member of the St George Snow Shoe Club and zealous promoter of lacrosse. Beers was the codifier of field lacrosse rules, playing goaltender by the sport’s position, founder of the first national sport organization in Canada, the National Lacrosse Association; so tireless was he in promoting the sport and so resolved to make lacrosse Canada’s national sport that Beers was dubbed by historians as the “flaming lacrosse evangelist.”

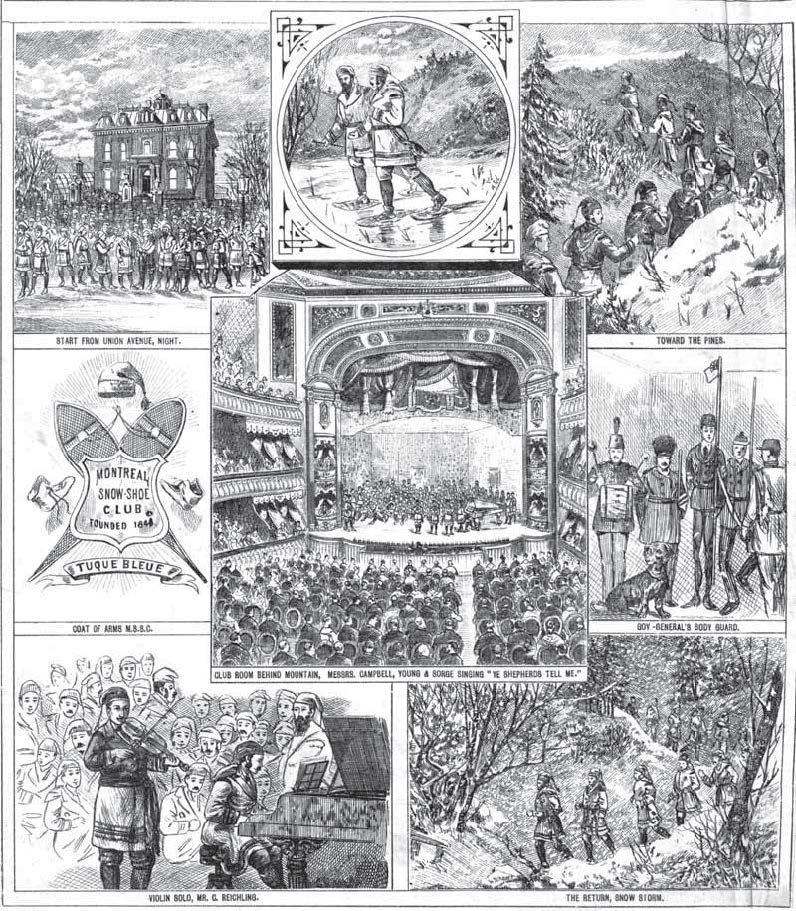

There was a pronounced altruism, an ethos endemic to the snowshoeing club members, particularly within the MSSC but eventually shared as part of all clubs. For example, in the early 1860s with the perceived threat of annexation posed by the American Civil War, resulted in praise showered on ‘fit’ snowshoers as ready recruits should conflict become reality. In fact, club musters were often cancelled to allow members to attend military drill sessions. At annual dinners, members rallied fiercely to the strains of God Save the Queen and Her Royal Highness Queen Victoria was toasted repeatedly amidst “raucous cheers.” Similarly, speeches at the gatherings proclaimed fine qualities such as perseverance and self-denial of snowshoers in “cultivating bodily superiority.” By the late 1860s, coincident with the rise in popularity of lacrosse, engineered in part by the latter sport’s champion, George W. Beers (described above), the number of snowshoe clubs grew rapidly among Anglophones in Montreal. There were French Canadian clubs, like Le Trappeur but there just wasn’t the active interest on the part of French-speaking Montrealers. The snowshoeing presence within the city was very pronounced and could best be highlighted by one example — many could be cited – of a ‘concert’ put on by the MSSC in 1878…

Grand Concert of the MSSC at the Academy of Music, Montreal, 25 January 1878. This illustration was published in the Canadian Illustrated News. Source: MAAA Scrapbook.

The Academy concert itself was organized as a series of living tableaux interspersed with songs, accompanied by piano and violin if the bottom left image is accurate, all rendered by MSSC members in an effort to show the public what a club tramp would look like. Clearly, it was stylized club-self promotion. And yet it does portray public interest in the sport as well as the perceived ethos of the snowshoe fraternity, a kind of Canadian-ized hearkening to the ideals of knights, almost mirroring the 12th century knights of King Arthur’s Round Table. Indeed, the circular table, deliberately constructed to symbolize every knight’s equality, reverberates in The Bounce – see above – the rite of welcoming and celebration performed by a circle of snowshoers. Because many tramps took place in the evening, this attribution of k/nights carries an apt and lovely double entendre. The seven outer frames of the Grand Concert illustration are self explanatory, inclusive of the governor general’s body guard alluding to the militaristic bent of the MSSC and British allegiance reified later the same year in the Snowshoers’ Arch noted previously. And, if the centre image showing the concert hall and concomitant press reports are indicative, this public display was very well attended and received by Montreal citizenry. Of passing interest, this tableau entertainment format was so well enjoyed that some 4-5 years after the MSSC Grand Concert at the Academy, the most famous athlete of the era, world champion oarsman, Canadian Ned Hanlan, mock-rowed a stationery rowing shell on the same stage to thunderous applause of the crowd. Literally, these events were theatres of sport in this period.

The other form of snowshoeing that really captured public imagination and promoted the growth in the number of snowshoe clubs across the city and elsewhere in Canada was snowshoe racing, the more competitive aspect of the sport. At first, in the mid-1840s, races were sort of long-distance ones when the snowshoers would halt 2 or 3 miles from their destination and a challenge would go up to be the first to get home. In an effort to attract public attention and to flaunt their athletic prowess, the Mile End (originally a limstone quarry area that became a vibrant city hub by the early 20th century) horse racing course in Old Montreal was used for the competitive events. Of considerable interest, these early races almost always included Native Canadians, very likely from the Mohawk or Kahnawake First Nations’ reserve on the south shore of the St Lawrence River. The nature of the events varied widely from sprints to several miles in length and prizes, at least in early races were often monetary; for example, an 1851 6-mile race carried a $30 first prize. By 1860, prizes for the mostly middle-class snowshoers were in the forms of silk sashes, belts, medals, and small cups as trophies. An early, circa 1875, informal race characterization:

The MSSC shifted its racing venue to the grounds of the Montreal Cricket Club and launched race events’ advertisements in the local papers coincident with the rising popularity of sport transmitted in the media. As an example, the following 1862 MSSC annual race “fixture” appeared in the Montreal Herald:

Montreal Snow-Shoe Club

ANNUAL RACES

To COME OFF on the GROUNDS of the

MONTREAL CRICKET CLUB, St. Catherine

Street on,

Saturday Afternoon next, 8th inst.,

at TWO o’clock punctually,

(Weather permitting)

INDIAN RACE OF FOUR MILES-Open to all, for a Purse of $20.

HURDLE RACE-Over Four Hurdles, 3 feet 4 inches high, open to all, for a

Prize Belt.

ONE MILE RACE-Open to all. Prize a Silver Medal.

RACE of 150 YARDS, in Heat-Open to all. Prize a Silver Medal.

GARRISON RACE of Half-a-Mile-Open to non-commissioned officers and

privates-Regulation Snow-shoes-Prizes, 1st $5, 2nd $4, 3rd $2

CLUB RACE OF TWO MILES-Open to Mem-[sic] only. Prize a Silver Cup.

HALF-MILE DASH-Open to all. Prize a Silver Medal.

No racing allowed with Snow-shoes under 10 inches width.

A list will be found at “Dolly’s,” where Entries can be made until 12 o’clock,

noon, on Saturday. Badges maybe obtained at Pickup’s and at Dolly’s,

PRICE OF ADMISSION-Ladies, free; Gentlemen, 25 cents; Sleighs, 50 cents

Honorary Steward;

Lieut-Gen. Sir W. F. Williams, K.C.B.

Stewards:

Col. MacKenzie, C. B., Edwd. M. Hopkins, Esq.,

Col. Kelly, C.B., Augustus Heward, Esq.,

Col. Connolly, D.A.G., C. J. Coursol, Esq.

I cite the full ad for may reasons. With some exceptions, it became the template for most racing events for the next few decades. Furthermore, the ad reveals a lot about the nature of these events. Note the first race, the “Indian race of 4 miles” was for money, was open “to all,” and was the longest event on the race card. With the exception of the garrison or military race – these were Civil War times – all races were shorter than the “Indian” race and all were contested for a belt, a medal, or a cup – materialistic prizes to be coveted and displayed. While white men could participate in the four-mile “Indian” race – hence the “open” designation – it was just understood that all other events were not open to Natives. Native racing skill was acknowledged and assumed to be heritage-related. Thus white competitors felt Natives would have a ‘natural’ advantage and did not want to be shown up by their perceived, sadly, social non equals. The event that has long intrigued me was the hurdle race or 2nd race on the card. Very likely, it arose from horseracing venues, was attempted and then inserted into racing matches…

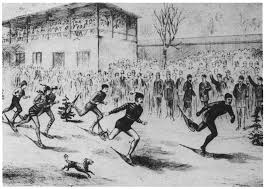

1892 MAAA Snowshoe Hurdle Race, likely at Westmount MAAA Grounds. Source: MAAA Scrapbook

This 1892 snowshoe-race hurdle image suggests the hurdle was fixed, could not be knocked over if inadvertantly touched; it looks like the lead racer has caught the toe of his ‘shoe,’ and is likely about to tumble. The art of snowshoe hurdling might have been to gently touch the tail of the lead snowshoe onto the front edge of the hurdle and then carry the back-foot snowshoe over the hurdle, not touching the wooden frame; snowshoeing “laws,” framed in 1878 stipulated that the competitor could not touch a hurdle with either snowshoe…it had to be cleared with a distinct jump. I surmise it was one of the more both skilled interesting events, the latter especially for the spectators – “ladies free, gentlement 25 cents, sleighs 50 cents,” in the 1862 ad above. Note the snowshoe width limitation in the same ad indicative perhaps of competitors trying to gain an equipment advantage, along with instructions about how/where to enter and finally, the listing of race “stewards,” the latter clearly reflecting social class and military (“Col.” or colonel) prestige.

Amplification of two snowshoe racing behaviours is warranted. One is gambling. If the adage, ‘if it moves why not race it’ was axiomatic in sport so too is its corollary, ‘if we can race it, let’s bet on it.’ A veritable explosion of interest in snowshoeing occurred just after Confederation in 1867 as clubs in the city had to restrict the number of new men seeking membership. Most pronounced was the influx of spectators at race events, as many as 5000 people were in attendance at races by the early 1870s. Police had to be hired by the MSSC for its annual races in order to keep spectators from spilling onto the track and interfering with the races. The major reason for the seemingly sudden spectatorial enthusiasm was because of gambling inclinations and opportunities. Racing, not the “tip-top jollifications” of tramping became the cynosure of the public eye and not just at the formal race venues. In 1868, the premier white snowshoe racer was an MSSC member, W.L. Maltby, later one of the founders of the MAAA. Maltby set out to break the half-mile race record by racing alone down Sherbrooke Street. Wagers were made openly in the press about Maltby completing the half mile in under 2 minutes, 50 seconds. When he did so, odds were immediately set for another race to be completed in even less time. In the following year, the press reflected pre-race betting interests for an annual race by declaring Maltby was “high in flesh” – meaning not fit – and gambling odds were set at 2 to 1 against him winning the mile event at the Dominion Snow Shoe Club races.

During the 1870s, clubs insisted on prospective competitors paying an entrance fee, not to cover race costs but to keep betting odds stable if favoured, talented racers did not show for events, thereby spoiling betting calculations among the public. Annually during the 1870s, the Montreal Gazette printed race cards complete with betting information – very similar to horserace cards – to cater to the public zeal for the sport and associated gambling interests. And, to enhance gambling odds and increase the lure of uncertainty of outcome, better competitors were ‘handicapped’ such that they had to start calculated yards behind the start-line. Thus the order of events at race meetings became standardized. In specific order, the card included a two mile Indian race, an open one mile, a hurdle race, a half-mile boy’s race, a 100 yards dash event, a garrison or open half mile race, the premier two mile club race (for each host club), and a final half-mile dash. Much like the 800-metre track race today, the half mile club race was regarded as the “experimentum crucis,” a scientific term meaning the decisive or crucial, determining experiment/race – the true test of stamina and racing superiority. Sprint events were conducted in heats and to win, the victor had to win two of his heats.

As commercial and betting interests escalated, tracks were cleared and prepared for the races with snow-packing and creating wider tracks along with hiring professional surveyors to set accurate distances – all in efforts to standardize the sport and equalize racing conditions, a hallmark of the transitions to modern, organized sport standardization. Race-starts were varied, drop of a hat, tap of a drum, verbal ‘go’ until a starting pistol was inaugurated and first reported – pun and double meaning of pistol report intended – in 1868. False starters were penalized one-yard back of the starting line for each false start. Prizes became elaborate with silver tankards (silver or pewter drinking mugs), crystal service sets, claret or wine jugs, dressing cases, sets of razors, writing cabinets, and the coveted “splendidly carved” meerschaum pipes (expensive smoking pipes made from the mineral sepiolite) that could be openly displayed and used at social occasions. Hotel proprietors donated special prizes in hopes of securing dinner patrons. Snowshoeing’s commercialization was cemented by all of these gambling and competition-enhancing elements. Concomitantly, prowess and skill were enhanced; 5 minute, 50 second mile times – enviable in foot race performances even by contemporary standards – were common in the 1870s. Notwithstanding the obvious pedal impediment to accelerate on the snowshoes in sprint events, the 100-yard record was 13.5 seconds, merely 3.5 seconds slower than the normal foot race track record at the time; however, athletic logic suggests to me that the snowshoe 100-yard race was from a running start up to the actual starting line when the start-time began.

The second behaviour endemic to snowshoeing during this era was the very pronounced discrimination against Natives. To the best of my knowledge, no Native was ever considered for membership in a snowshoe club. Performance times by Natives were superior to those of white racers. That ability was stereotypically perceived as innate and owing to their crowd = betting-drawing feature, the “Indian Race” was always the first one on almost every club’s race card. All other races were just known to be closed to Natives because whites regarded them as socially inferior and did not want to be ‘bettered’ by them in the races. Discrimination, even derision, and ridicule of Natives was common. All prizes for Native races were monetary, the assumption being that money would be a stronger incentive to Natives, thereby creating a more spectator-pleasing, competitive environment. Furthermore, the money was given in small silk purses right after the Native event while the other prizes often were given at social, club events following the race-meeting. Natives were not invited to such celebrations. Becket’s history of snowshoeing is replete with derogatory and racist terminology. “Novelty” races by the mid 1870s included a half mile event wherein each competitor dragged a toboggan in each of which a “young savage” was strapped. Similarly, 100-yard showshoe-potato races were conducted; each Native competitor had to pick up a potatoe placed at every yard along the stretch and return them one at a time to the starting line. The intent of such novelty events was for white ‘amusement’ with betting in the potato race centered on when each competitor would quit from exhaustion. The worst example of racism and just mean spiritidness in my view, was exemplified when a pair of Native females, overweight in the selective process, were induced to race each other, all for the ‘fun’ of gambling on the outcome and ridiculing the participants. In the same spirit of derision and perversion – though not perceived that way at the time – of entertainment, extra money was offered to Natives if the winner could beat any known event record. The only comparative mockery of white racers was reserved for military personnel, policemen, and firefighters, all presumably less adept at snowshoeing and therefore often put in events at the races for comedic and gambling prospects.

One glaring exception to the Native discrimination rule was accorded to the premier racer of the 19th Century, the Native man, Keraronwe, likely from the Caughnawaga area. He was without peer in the “Indian” races from 1868 to around 1880. Even Becket could not restrain his admiration for Keraronwe’s superior talent and yet he was very much the exception to the blatant racism attached to snowshoe events in this era.

Two sports served to buffer and even enhance snowshoeing’s popularity in Montreal. One was the accelerated rise of lacrosse and the creation of lacrosse clubs beginning in the late 1860s and lasting for more than 40 years. It seems that the summer sport attracted a similar participant-clientelle to the endurance, racing, and competitive aspects of snowshoeing. Perhaps the two sports were reciprocal, kind of fed each other during different seasons. The other sport or physical activity that, at the outset, threatened to engulf and displace snowshoeing was ice skating. Skating had been in existence for some years but just wasn’t popular until skate manufacturers and the patent process permitted skates to be more available. It might be too that snowshoeing modelled the potential for enjoying winter recreation. Whatever the case, throughout the 1860s and 1870s, a skating “mania” existed and extended geographically from the Gaspé peninsula to Sarnia (the western-most point of inhabited Ontario at the time). At the same time, skating’s popularity was mainly recreational and crossed most social classes. Ice-hockey, though in existence, did not become popular until the 1890s. For those in the upper classes, skating offered the opportunity for ostentatious social occasions in the form of skating carnivals:

1870 Skating Masquerade at Montreal’s Victoria Rink, Notman Studios, Source: MAAA Scrapbook

This colourful, magnificent Notman rendition of the skating ‘carnival’ highlights the interior of one of the first – built in 1862 – and by all accounts “finest” indoor skating rink in the world. One can only imagine the grandeur and sheer delight of preparing one’s costume for and then attending such an event, one that was repeated often in the 1870s and 1880s. Moreover, the day after such masquerades, the local English press published a complete list of all the skaters and their respective costumes, very likely of some self-reflective importance to the upper social class participants. Skating itself could be done anywhere and in Montreal, the St Lawrence River was a prime public location as were rinks built at cricket clubs and other sporting venues within the city. A revealing indicator of the blend with skating along with snowshoeing’s retained premier winter sport position in Montreal was the inclusion of a snowshoe contest at the skating races held at the Victoria Rink on 1 February 1873. It was a best of 3 heats covering 5 laps of the ice surface. My best guess is the racers used ‘spiked’ frames in their shoes, nails driven into the hardwood for traction. The initial intent may have been to capitalize on the sport’s popularity and thereby boost the draw to skating and/or to belittle the athletes with presumed equilibrium problems on the ice. In fact, snowshoe racers and race organizers often iced outdoor horserace tracks for snowshoe races; the format was not new. Whatever the motivation, the snowshoe races on ice captured public enthusiasm and the races became regular features on the race cards of many rinks, indoor and outdoor within the city. Coupled with enhanced commercial and organizational aspects of snowshoeing – the 1878 publishing of the “Laws of Snowshoeing,” for example – its gambling and spectatorial appeal meant the sport retained its immense popularity throughout the 1870s and 1880s. In fact, snowshoeing and its devotees showcased the sport and other winter sports to the world with the Montreal winter carnivals held between 1883 and 1889.

The whole concept of carnival – carnaval – is centuries-old. Pieter Bruegel’s 1559 painting masterpiece “The Fight Between Carnaval and Lent” illustrates the underlying theme of the carnival – especially its religious context – historically and in terms of human consciousness. This painting typifies a kind of template of the whole concept pervading carnival-as-special-event. The painting depicts Shrovetide, a time of celebration in the Christian calendar when three days of revelry and excessive festive behavior immediately precede Ash Wednesday and the ensuing forty weekdays of Lent leading up to Easter:

The depiction is busy with people, as were most of Bruegel’s works. Certain aspects of the image are pertinent to the carnaval-esque theme. Near the lower left is a lusty (full codpiece over his loins), gluttonous figure astride some kind of barrel and brandishing a lance carrying a suckling pig; this individual is Carnival. His followers all seem to be relishing foods of some description – pancakes, waffles, sausages, and eggs. By contrast, facing Carnival, in lanced opposition framing the ‘fight’ from the painting’s title, is the gaunt figure of Lent, a thin and haggard female. Her foods are more modest, pretzels, fish (her lance carries one), and figs while her followers are more supplicant and subdued than those of Carnival. Many of the traditions of the Christian church are inextricably bound in the solemn traditions of Lent beginning on Ashe Wednesday and culminating 6 weeks later on the night before Easter. Excess and austerity, celebration and denial, polar extremes of existence are so vividly captured in Bruegel’s art-work. Carnaval or the spirit of Carnival-esque festivities runs deep in western culture and carnivals are held all over the world, usually in warm geographical locations and seasons. The concept of carnaval as festive and festival is almost ethereal, as though the whole notion or feeling of carnival has a life of its own. Its pattern of processions, parades, revelry, and excess appear to be the essence of carnivals everywhere, all so well compressed into The Fight Between Carnaval and Lent. And so it was that Montreal established its frozen festivals of winter sport carnivals that reached a crescendo of popularity during the 1880s.

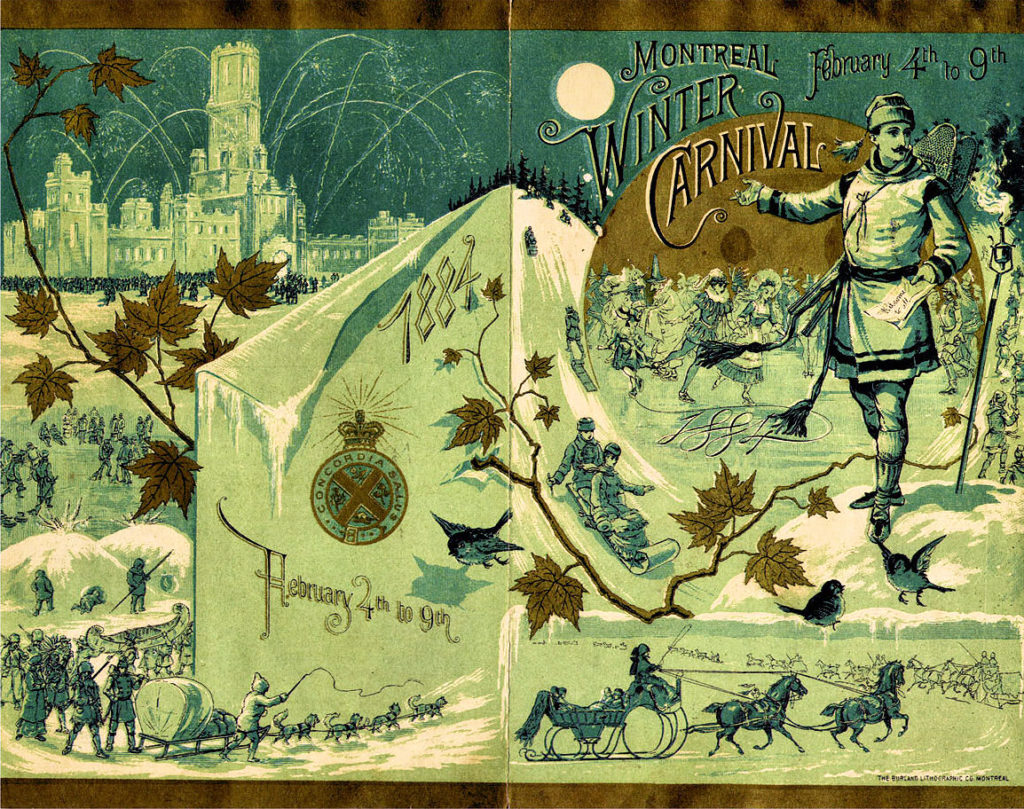

The Montreal winter carnivals ran annually – with two exceptions – from 1883-1889. It was the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association and in particular MSSC member R.D. McGibbon who conceived the idea of creating a theatre of Montreal winter sport in which snowshoeing and snowshoers would be featured components. At the time, Montreal sporting clubs were at the forefront of organizing sports with codified rules, governing bodies, championship events etc. That leadership seemed to lend itself to the creation of the frozen festivals, the winter carnivals of the decade. The week-long set of events was held in the last week of January or the first week of February each year. Of coincidence to the current pandemic and its impact on social events, the 1886 winter carnival was cancelled owing to a smallpox epidemic. For the proposed 1888 carnival, disputes among the railway companies largely responsible for bringing a huge influx of tourists along with the powerful MAAA who withdrew their financial and organizational support citing conflicts with city administrators all resulted in cancelling the event until the last one 1889.

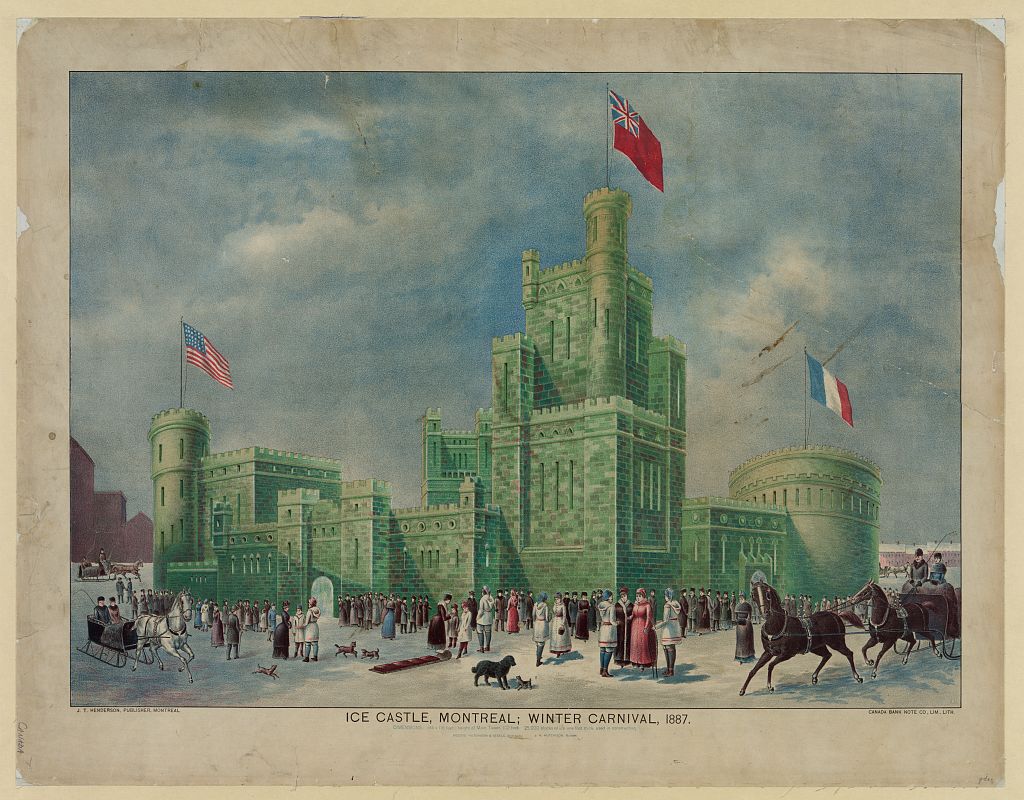

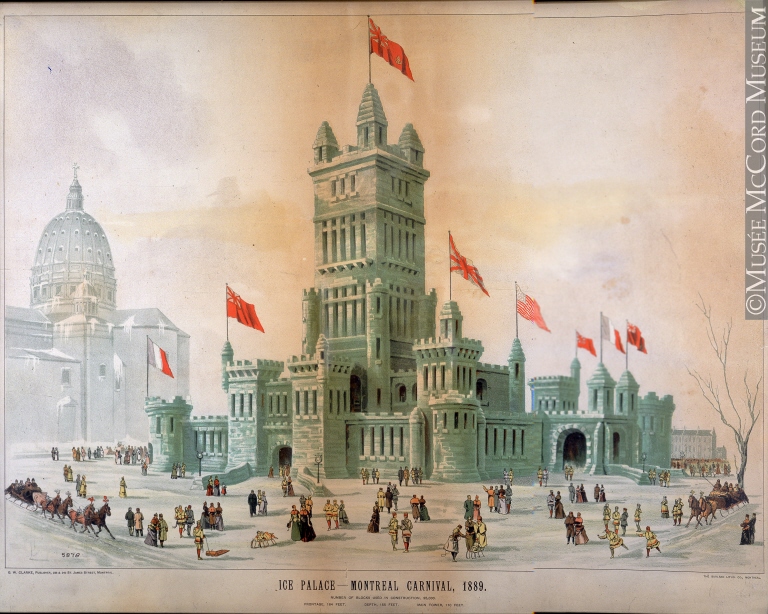

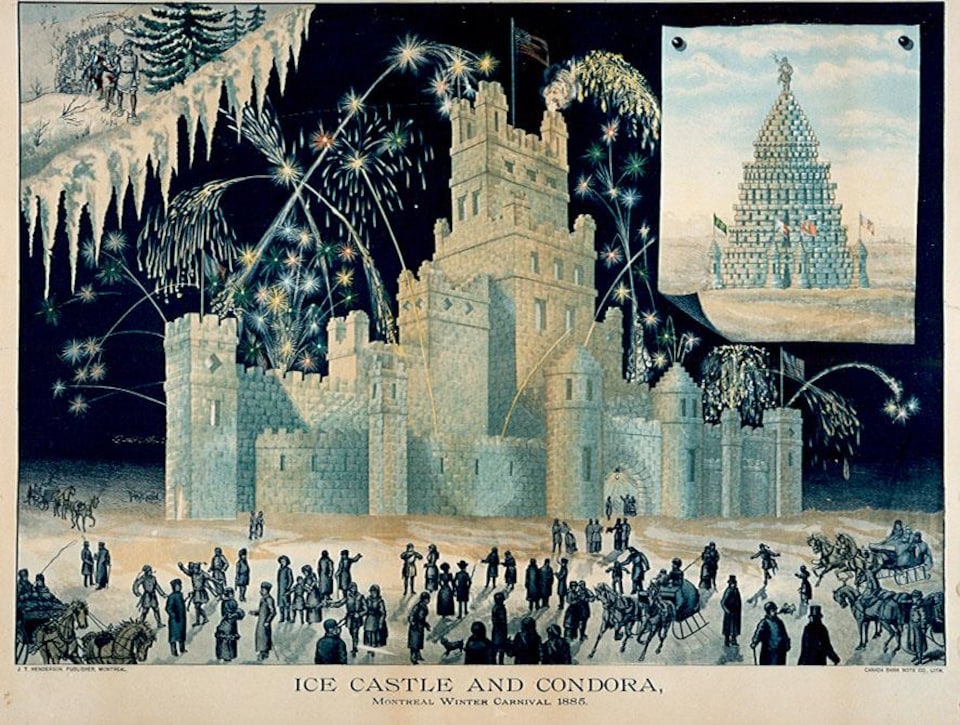

Structures erected as the “props” for this winter theatre of festivities varied little over the decade – the ice palace or central feature of the carnival; an ice condora and ice lion, and a living arch. These became the symbols and indicators that each carnival was in place and sanctified. Each year, centre stage for the Montreal carnival was the construction of the ice castle, always set on Dominion Square (Place du Canada) in the heart of the city and always under the auspices of an architectural firm. The cue, apparently, for constructing the castles came from St Petersburg, Russia where a magnificent ice palace was built in 1741 “for the amusement of royalty, the satisfaction of the curious, and the wonder of the world.” The St Petersburg edifice was hailed as an “ice phantasmagoria.” For the Montreal castles, ice was cut in 500-pound blocks from the Lachine canal on the St Lawrence River; the finished castles reached heights up to 130 feet. Images of 4 of the castles clearly illustrate their grandeur even by contemporary standards:

The first Montreal Ice Palace, 1883, evergreen boughs iced as roof domes, reprinted with permission

The first Montreal Ice Palace, 1883, evergreen boughs iced as roof domes, reprinted with permission

The 1884 Palace composed of some 16,000 blocks of ice, ‘welded’ together by water sprays that froze them in place. The presence of people gives a good sense of perspective on the size of the structures

A very stylized, likely lithograph card of the 1887 Castle

The 1889 Palace, reprinted with permission

Clearly, the palaces or castles became more elaborate over the decade. The interiors could be accessed through portals or gates; some were lit either by electric lights and/or by torches. ‘Windows’ were formed by very thin sheets of ice and cannons were mounted at select points along the walls. Each castle was always the centre piece of the carnival. There were two other ice structures erected, occasionally, during the event. An ice “condora” was situated in the Champs de Mars’ area of old Montreal. built from twelve thousand blocks of ice. In outline it was a stepped cone – a kind of iced Tower of Babel or leaning tower of Pisa, without the leaning – fifty feet in diameter, one hundred feet in height, and surmounted by a snow statue twenty-four feet in height, representing a white Canadian with snow-shoes. In its construction the condora was built of concentric walls increasing in height as the diameter decreased. It was approached from the interior, and during the times of celebration hundreds of the members of the snow shoe clubs could stand on the tiers encircling the condora. Symbolically, the 24-foot snowshoer was a mirror to snowshoe club’s dominance, a giant testimony to showshoeing. Ironically, the carnivals were the last hurrah for the sport’s dominance.

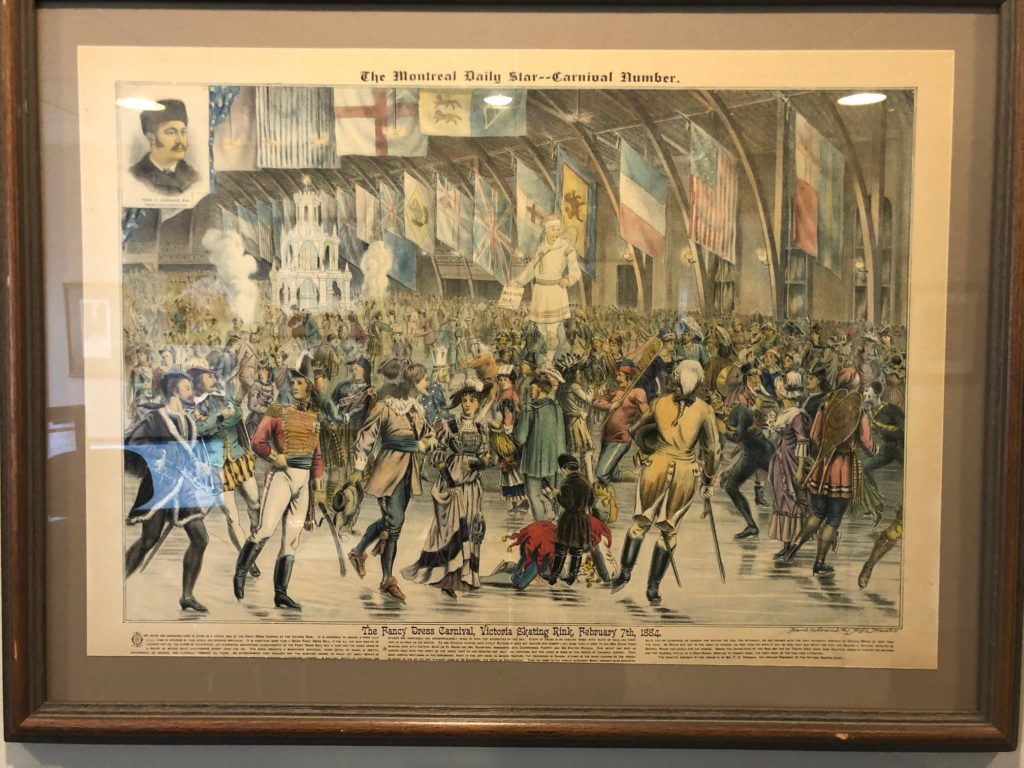

There was a third ice structure, a colossal statue of a lion set in the square at Place d’Armes facing the Notre-Dame Basilica. The pedestal for the replica was twenty feet high and surrounded by four buttresses, the main portion was hollow and illuminated by electric lights, which imparted a spectacular effect at night, similar to the ice palaces. All of the ice structures set the stage for the organizational frenzy that took place each year. For example, the Great North-Western Telegraph Company was hired to advertise the program for the carnivals across the New England states. Special invitations were sent to the mayors of major Canadian and American cities, to the federal cabinet ministers, and to the lieutenant governors of each province. Great care was taken in the little details, like standardizing “hackmen’s” (taxi-drivers of horse-drawn conveyances), soliciting the cooperation of the fire department to hose the ice structures and rink surfaces, and having the harbour commissioner procure a generator to run the electric lights at the various venues inclusive of the curling areas on the River. The Canadian Illustrated News carried images of the carnivals and the New York Herald ran articles about events, rules, and prizes. For each carnival, The Montreal Daily Star published a “carnival number,” with a double fold-out section that could be saved and hand-coloured like this one from 1884:

MDS Carnival Number, 7 February 1884. It is the actual newspaper printed, hand-coloured, and dry-mounted on a firm backing. I found it years ago in an antique store in St Mary’s, Ontario. For 25 years, the picture hung in my office at Western University and it still adorns one office wall at home.

The sports featured at the carnivals were snowshoeing, tobogganing, skating (figure and masquerades on skates), ice hockey, ice trotting (equestrian), and curling. Weather permitting, for some of the annual carnivals, a children’s carnival took place about 10 days before the main event, a kind of mini-rehearsal for the carnivals.

The real carnival was in the streets of activity, the landscape of the events. In the anglophone, west end of Montreal, the roads were described as “crowded with sleighs,” or “crawling” with people “bent” on enjoying

themselves in sliding, skating, or snowshoeing – a veritable Montreal mirror of Bruegel’s vision of mirth and celebration and activity illustrated in The Fight Between Carnival and Lent. At night, the ice palace had a red fire burning from inside the structure giving the appearance of huge blocks of ruby-like ice. People remarked on its alabaster columns, and the press was ecstatic in description: “The moon cast a silvery light over the landscape, bringing out the mountain in bold relief, and casting an additional charm over the scene.” The sporting events seemed almost secondary, even tertiary to the more carnival-esque feel or festive spirit surrounding the whole landscape, city-scape, and sport venues.

By far the most popular event of each carnival was the Wednesday evening mock-attack on the ice palace. A “seething, swaying, good humoured mass of humanity” gathered in thick lines or huddled in clusters anywhere within viewing distance of the ice palace. On cue – the whole “attack” was very carefully choreographed – hundreds of snowshoers, from all the local clubs, carrying lighted torches marched in procession from the heights of Mount Royal to Dominion Square, encircled the palace, and ignited roman candles while the interior of the building was illumined, in colorful response, by firework volleys of a “pyrotechnic storm.” Amidst great cheering and loud applause, the palace was declared open, and the ubiquitous Victoria Rifles band played the national anthem followed quickly by “Yankee Doodle” to amuse the coveted American guests. It was pure hibernal theatre, carnival and carnaval at its winter best. At one carnival, 4000 people came to the McGill College gates to witness the start of the snowshoe steeplechase race and to wager on the outcome.

The “attack” on the ice palace, 1885 Montreal Winter Carnival; the Condora structure is imaged top-right.

The Montreal winter carnivals up to the last one, were both kaleidoscopes of winter celebration and huge commercial successes. The crowning, in the Montreal elites’ perspective, were the masquerade skating ball at the Victoria Rink (one participant paid $250 for an Othello costume for the 1885 masquerade) and then the Grand Fancy Ball always held at the Windsor Hotel on the last night. The 1889 Carnival seemed dehydrated in comparison to the earlier ones. Interest seemed to fizzle or perhaps the tasks of organization and hosting became overwhelming. The last, 1889 ice castle attack was described in this manner by the press:

Merrily rang the chimes of the fairy-like but fated Ice Castle last night,

as the multitudes flocked to Dominion Square to see the siege of the

fortress by the army of the combined snowshoers of Montreal. . . .

For a moment, the batteries of the enemy were hushed. Goaded on,

nearer and nearer, by the very silence within, the enemy approached.

Now was the moment. In the twinkling of an eye … rocket responded

to rocket, torbilions hissed through the night air, and cosmetic gold

stars illumined the scene. ~ Montreal Daily Star, 7 February 1889

One intriguing element about the 1889 version of the Montreal winter carnivals occurred in the Montreal Daily Star, the main chronicler and supporter of the carnivals, on 5 February, the second day of the 1889 carnival proceedings. A series of what at first glance appeared to be grotesque cartoons were printed in detailed sketches along the top border of the first six pages of the eight-page edition. About five or six inches in height, the whole cartoon was a parade of carnival vehicles and characters led by a named and prominently-figured “King Carnival” seated on a four-horse sleigh, followed immediately by a smaller sleigh pulling Uncle Sam and then one filled with three clowns or fools pulled by a single black horse. It was as though carnaval was receding into textual format away from the commodified and dehydrated version of that year. The “inverted universe” of carnival was subverted to the press in cartoon-form. It is eerily reminiscent of Bruegel’s painting, at least of the Carnival-with-retinue rendering of his masterpiece. The inference is that the essence of carnaval is one of its own device, or, it is a kind of attitude of celebration that has a form of its own.

Overall, the ensemble of carnivals became too complex, too commodified, and lost its special appeal in deference to commercial and new sporting – ice hockey, in particular – interests. In effect, in many ways, the carnivals were hollow dramas of Montreal sporting myths. And part of that mythic rendering was the ebb of snowshoeing and its dominance as a Montreal sport. By 1885, at the height of the Carnival’s popularity, the MSSC alone numbered 1000 members and there were at least 25 clubs in the city. Furthermore, showshoe clubs were in existence from Terra Nova, Newfoundland to Winnipeg, Manitoba. However, public and participant interest moved more and more to the racing forms and their attendant gambling prospects. In point of fact, racing flourished and expanded too rapidly by the late 1880s in Montreal fuelled in part, perhaps by the Merchants’ Cup given in 1884 by Montreal merchants for an annual five-event competition. Similarly, the consummate sports promoter, New York city’s Richard K. Fox offered awards for a series of five mile races to become the championship of Canada. Tourist dollars wrought from the carnivals lead to this broad attempt to commercialize snowshoeing when the sport was actually waning in popularity. Tobogganing, especially on prepared, iced and banked chutes, ice-skating and its rapidly emerging derivative, ice-hockey, the latter popularized by the carnivals, captured public interest more fervently than walking or racing on “three feet long sieves.”

Tobogganing, Mt Royal slide-chutes circa 1885

The decline in snowshoeing’s prominence was as swift as had been its meteoric rise in the late 1860s and 1870s. The construction of skating rinks throughout the city inspired public participation in that sport over snowshoeing, the winter activity that necessitated more time to find a place to tramp than would be needed to get to a rink to skate. Furthermore, snowshoe club members themselves were lured more and more to play ice hockey as part of the emerging trend toward team sports. The MSSC tried to capitalize on skating’s popularity by holding their races in conjunction with skating races, to no avail in sustaining interest. The kind of death-knell to snowshoeing came with the results of the first Canadian snowshoe championships held in 1894 in Quebec City. Very little public or participant interest was associated with those races. The jubilee celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the MSSC in 1890 were filled, fittingly and prophetically, with reminiscences and nostalgia spoken and expressed about the good old tramping and racing days, days long gone.

About 25 years ago, a group entitled les amis de la montagne – trusted friends of mount royal revived the spirit of the Tuques Bleues as one of the elements of promoting and sustaining the viability of Mount Royal as a park of remarkable heritage in Montreal.

Upholding the Tuques Bleues’ Tradition 2021 website. The lantern is so reminiscent of the torches used by 19th century snowshoers.

Annually, with the exception of Covid-restricted 2020, these “friends” organize an evening, lantern event on the mountain…

In my view, it seems such a fitting tribute to the halcyon days of Montreal snowshoeing and the founding MSSC club. Snowshoeing remains a Canadian pastime as well as a competitive sport. Founded in 2010, the World Snowshoe Association (formerly the International Snowshoe Federation) is the international organization that oversees snowshoe racing. Canadian and international athletes participate in snowshoeing competitions in both the Special Olympics and Arctic Winter Games.

On Mount Royal itself, affixed to trees, signage guides today’s snowshoers along the Mount Royal trails – such a modern, stylized snowshoer…at the least the bleue hue reflects MSSC heritage…

While I can never understand or condone the racist and social class insulting that were part of the 19th century snowshoeing ethos, I cannot help but be in wonder of the trampers, their athleticism, their jollifications, celebrations, and contributions to the landscape of Canadian sport. Each time that I ran ‘the snake’ on the mountain, beginning in the 1970s, I was acutely aware of the historical richness of the topography. Always, I would reminisce and now I tumble home to the memories of those k/nights of the snowshoe, their blanket coats, their songs, racing prowess, social inclinations, racially discriminatory practices, and all attendant snowshoe-related behaviours – the carnaval of tramps and tramping.