Jack

Throughout my life, I have been so fortunate to have so many mentors, people who taught me, guided me, supported me, constructively (mostly) criticized me, and greatest of all, inspired me. One of my earliest preceptors had a profound impact on my academic motivation, my career, and my burgeoning squash skills – John Russell Fairs, Jack, as we all know him. So much has been written about him in terms of his immense contributions to many sports, especially to the game of squash. Perhaps the best overall introduction to Jack is this video:

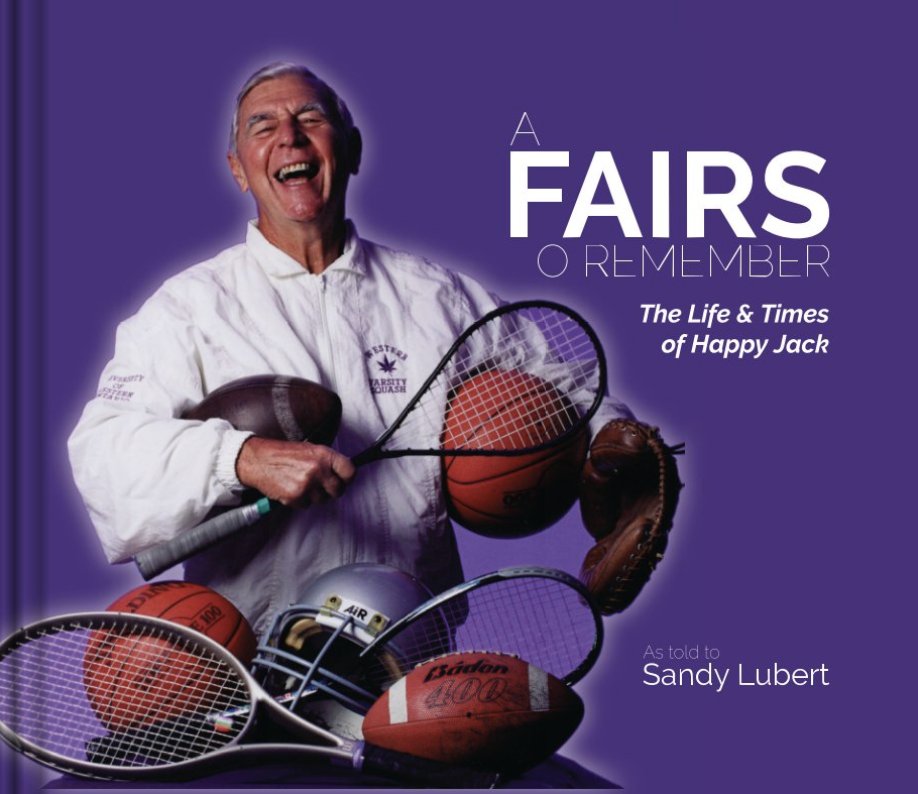

So very apropos of the mastery aspect of Jack’s impeccable skill as a true student and teacher of sport is the first image in the video. In the early 1970s, Jack was invited to bring a fishing team to the US eastern seaboard’s NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) deep sea fishing tournament. Not a sport at Western, Jack obliged, recruited some of his squash team members, travelled to the States, was loaned a boat and gear. Lo and behold, his team caught the biggest fish (tuna? marlin?) and won the trophy! In the broadest sense, he ‘gets’ sport, loves competition, and was devoted to his players and to delving deeply into the strategies, tactics, and skills of every game he knew. Perhaps this image that graces the front cover of the recently published, A Fairs to Remember: The Life and Times of Happy Jack (as told to Sandy Lubert) encapsulates Jack’s all-encompassing, electric and eclectic passion for sport:

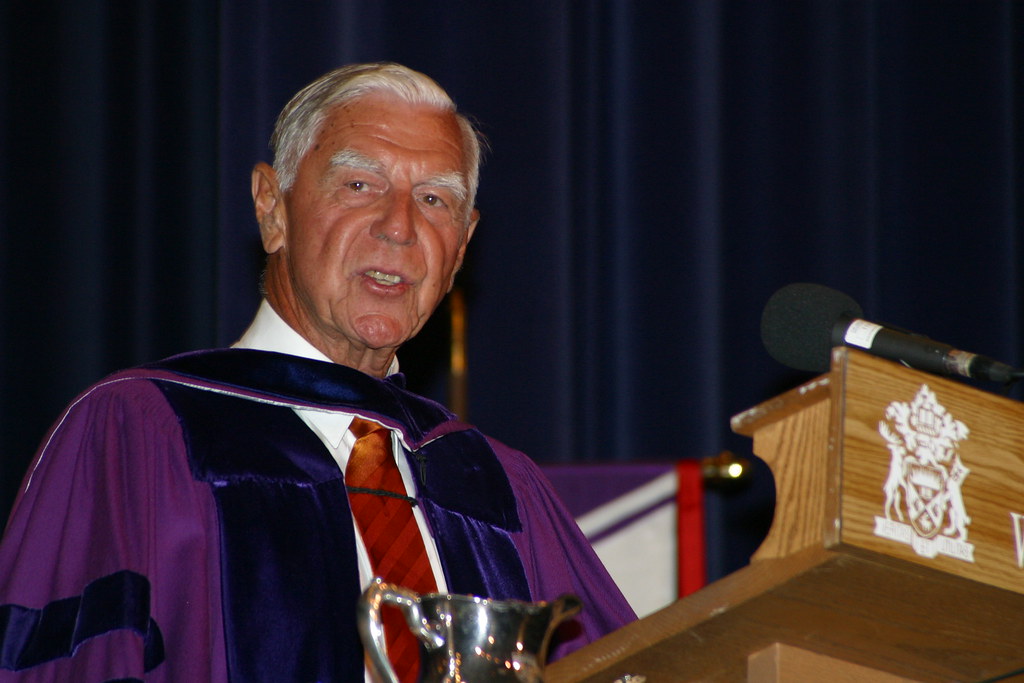

I met Jack at Beck Collegiate’s tennis courts in the mid 1960s (see my blog, courts…fives to pickleball) when he and his colleague, Dutch Decker came to watch some of us playing tennis on Beck’s outdoor, asphalt courts. Jack was looking for high school athletes with racket skills for potential development as squash players and Dutch was looking for badminton players – both for Western teams in those two sports. Fortunately for me, I seemed to meld with their expectations and I was recruited to come to Western during the last two years of high school to learn squash and play badminton with the university teams’ members. No one had ever coached me in any racket sport; I sort of picked up those sports by athletic osmosis. Jack was unwavering in his patience in teaching me the nuances of squash; we spent hours and hours drilling and learning its skills – the forehand, the success of which was entirely dependent on racket preparation; the backhand that had to be hit much farther in front of the lead foot than the forehand; the lob serve, Jack’s forte; the drop shot and cupping the ball to keep the bounce low; the double boast….And all the language he attached to the game – “hit that baby (the ball) like a sensen pill” (I had no idea what a sensen pill was but assumed it was something hit fast and hard); on the serve, lift the ball to “caress” the sidewall. He loaned me books on squash and later shared articles he wrote about different aspects of the game, controlling the ‘T’ (centre of the court), stroke mechanics, using the serve offensively instead of just putting the ball in play (“A Portrait of the Phlegmatic Server,” he titled the article adroitly), and holding shots for deception. Jack captivated me, captured my imagination, and certainly challenged my skills as a rackets’ player. His impact has never left me. In 2008, at Western’s Spring Convocation, I was honoured, deeply so, to introduce Jack on the occasion of Western conferring on him an Honorary doctorate degree – my speech – in prose form – is available here and the image below is Jack addressing Convocation on that occasion:

Modest about his athletic accomplishments in baseball, football, and basketball, he preferred to tell stories about those sports, the people with whom he played, the adventures he had. To me, Jack was dashing, witty, with mischievous eyes, an infectious laugh, and an unfathomable vocabulary. What is rarely noted about Jack is his intellectual gift, his incredible insights into culture/s, meanings given to the body, to physical culture, and to sport over millennia, and his ability to comb prodigious amounts of books, articles, artifacts, and then interpret those tomes into his teaching. In my estimation, Jack was a true scholar, perhaps one of the earliest intellectual academicians in the burgeoning field of Physical Education. He possessed an impeccable ability to understand philosophies, educational trends, and educators’ impacts and then teach classes of Undergraduate and Graduate students. The kind of catch-22 for me in this blog is that of trying to reveal and explain a person’s intellect, in this case, Jack’s gifts, his repertoire of knowledge, and his very unique methods of teaching an intellectual history of the body in western culture whilst endeavouring to do justice to what he knew and what he did.

As a young Physical Education (now, Kinesiology) student, I was deleriously happy pursuing my Undergraduate studies, playing two intercollegiate sports (badminton and squash), and learning everything I could about all sports, training, exercise physiology, human development…all in my then-assumed track to Medicine (organic chemistry was to be my gargantuan, ultimately impenetrable barrier). And then, in my 3rd year, I enrolled in Jack’s technically 2nd-year PE class, Physical & Health Education (P.H.E. 258), “A History of Physical Education.” Oddly, at the time, I had no idea he taught an Undergraduate theory course, or, if I did, I assumed it was a sidelight to what I could learn from Jack on the court.

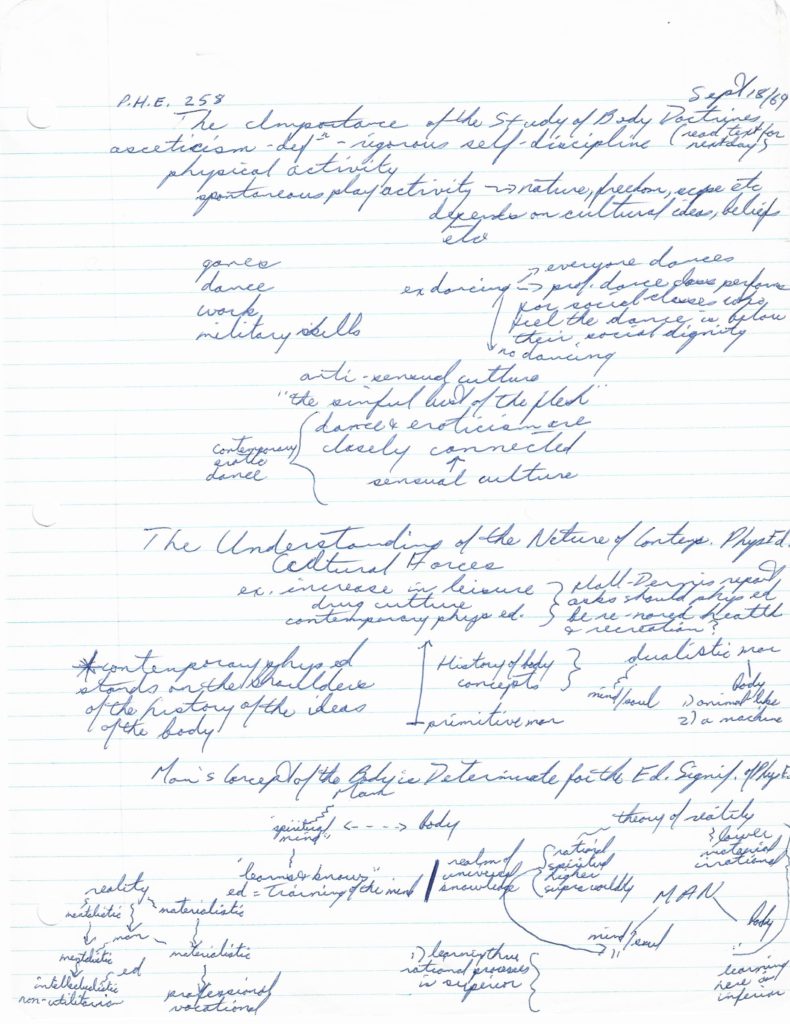

The 258 course was, as most courses were at the time (Fall, 1969), a full year (both terms’) course; that meant most theory courses covered a lot of material, had multiple tests, and final exams that typically included at least two-thirds of course content. There were about 60 students in the class, a mixture of 2nd, 3rd, and even some 4th year students. We were packed like sardines into wooden, one-arm bandit seats in room 114 Thames Hall, the PE building. It was, in retrospect, a terrible room for teaching though it didn’t seem so to us. The front and longer wall of the rectangular area had a dark oak, wood-framed double blackboard; overhead projectors were in use but mostly in Science courses. Jack filled the bladkboards with his lecture notes before every class and often wheeled in two portable blackboards, equally resplendent with his impeccable straight-lined and carefully crafted penmanship, and placed them along the width of the room. I don’t recall specific instructions from him but it was crystal clear we were just expected to copy the notes verbatim and doing so often took the whole one-hour class.

To state that Jack’s teaching style was unique is a proverbial understatement. He didn’t repeat was written on the boards; instead, he stayed at the front of the room, often leaning on the elegant, dark-oak in hue, wooden lectern, grinning with enthusiasm. From that place, he told stories, tales about his football coaching days, his experiences as a baseball catcher or a vignette about some particular athlete, almost anthing but course-content related. Those stories were peppered by his perfunctory declarations that “we” should get back to the course content; often his self-prompt to content focus was just a bridge to the next story. He knew many of us by name and would punctuate his narratives seemingly seeking affirmation by telling the story and then wryly looking at one of us, gently pointing his index finger, and saying, “…right, Don,” or “…you know…right, George.” If named, we nodded, frantically continuing to copy the notes. If someone weren’t paying full attention, then that was the person Jack selected for his pseudo-confirmation of the storyline. For myself, I loved the stories and still remember many of them, at least snippets of them. To the best of my recollection, Jack’s in-class narrations were just that, monologues from his mind and memories; unless rhetorical, I don’t remember him asking a single question of us nor do I recall any student ever asking a question.

Perhaps less engaged than me, some students quickly caught onto Jack’s pedagogical approach and took turns getting each other to “take the notes” so that they could skip class and rotate the note-taking. Jack knew it was happening and he exuded such an affable manner in handling the situation. He didn’t know everyone by name but he had an incredible memory for faces. When a student returned for his/her turn at note-taking, Jack would greet the attendance-offending student at one of the two doors to the room, extend his hand to the student and in a kind, easily heard, almost melodic voice say, “Hi, welcome back, Jack Fairs, course instructor.” Just as often, he’d wait until he was 10 minutes into class time to walk right up to the student’s desk to share his recognition greeting with them. And we snickered at his wit and at our centred-out classmate. Classes were small enough and we all knew each other well enough that receiving Jack’s overt I-know-you-haven’t-been-here acknowledgement was embarrassing and we likely made up that such instructor-noticed lack of attendance could affect our grade so the note-taking schemes fizzled quite quickly.

And all of the foregoing class context is just that, the environment in which Jack worked and his personal magnetism and mannerisms as a professor. It was, to me, window-dressing to the content of what Jack actually taught and the meanings I attached to his course content. Simply put, Jack Fairs was erudite and an absolute forerunner in what he taught in this course and in its/his Graduate course counterpart. Most extant, developing history of PE courses’ content was kind of one-damn-fact-after-another rote learning about different nationalistic systems of physical education, pioneers who founded those systems, and different approaches to modern sport such as the British public school ‘games’ ethic – the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton – or the ancient and modern Olympic Games’ movements. The omnipresent text used in the field was this 1953 World History of Physical Education:

I don’t know if Jack ever used it as a primary text but I do remember we had assigned chapters to read occasionally. If he did use it in earlier years of teaching his course, he quickly moved away from it stimulated, I suspect by his own unquenchable scholarly curiosity and vast – I now discern – knowledge about culture/s. He adopted a unique method to studying human movement, sport, PE, recreation etc using a cultural and ideological approach to analyzing cultural attitudes toward the body. Interestingly, Jack’s post secondary education was in the Sciences; he held an MSc degree from Columbia University with very little training, if any, in History and/or the Social Sciences. Until I read the recent A Fairs to Remember book about Jack, I did not know he has never read a novel in his life. I found that fact, if true, astounding because his reading of books from such fields as Anthropology, History, Science, Philosophy, Religion, Education, and many other academic fields was prodigious and laser-like in his discernment of meanings and implications. It was as though he possessed some personal periscope of perspectives as a lens through which he harvested meanings that cultures attached to the human body. For me, his impact was more akin to sharing a kaleidoscope of innovative ways to understand cultural views on everything from idolation and respect for the physical body to outright degradation of our corporeal beings. Singlehandedly, Jack funneled my intellectual curiosity and interests toward this form of cultural history of meanings.

I still have my notes from PHRE 258 encased in the original, dilapadated, legal-sized, manila file folder, significantly, the only set of notes I retained from my Undergraduate and Graduate education. At some point during the 1960s, Jack discovered this machine:

It was called by various names – a spirit duplicator or Rexograph but most commonly it known as the Ditto machine, precursor to the photocopier. Users, like Jack, created a waxed ‘master’ from a hand-written or typed document. Then, that master was attached to the drum and by feeding paper into the machine, the master created copies using the hand crank to press the master writing into the blank pages, one page at a time. The alcohol-based ink-smell was strong, very potent and we could tell how recently Jack had created ditto-machine notes by the odor retained on the pages as he distributed them in class. These handouts either amplified the blackboard notes or they provided greater context for the topic under discussion. My strategy was to make my in-class notes from the board, reference the ditto-handouts for studying purposes and eventually writing all over the ditto pages and underlining and/or highlighting what I felt was emphasized by Jack. Below is the lead-page of the first set of content notes I took in Jack’s class, 18 September 1969…

What is missing in this representation is what I felt after I left that first class. I had an immediate comprehension of how cultural forces had shaped western thought re the ascribed importance of the mind/soul over the body. It was so significant to me that learning/education/religions placed the mind on a pedastal and reduced the body to subservient learning and even to sin and lust, somehow inferior to the mind. It was an explosion of meaning for me, an Aha-moment that stood me up straight, hit the tuning fork of my values re contextualizing my experience from both realms of existence, mind and body.

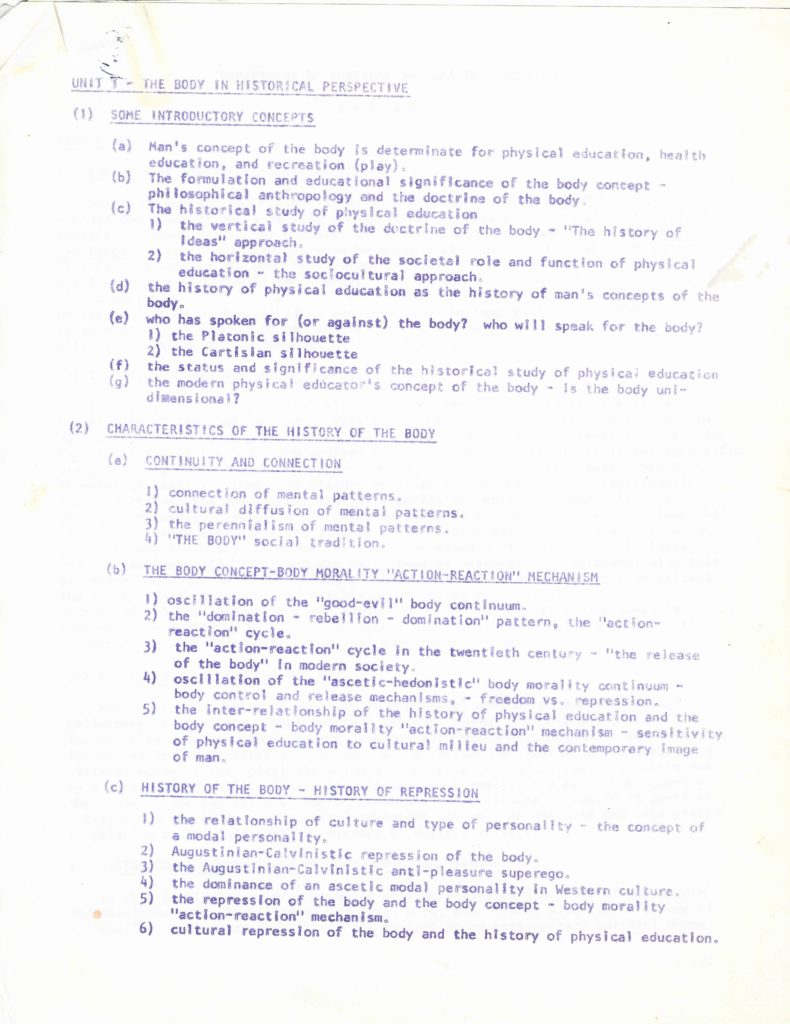

One of the earliest ditto-handouts we received in the course was a kind of synthesis of where we were going regarding course content…Unit I – The Body in Historial Perspective:

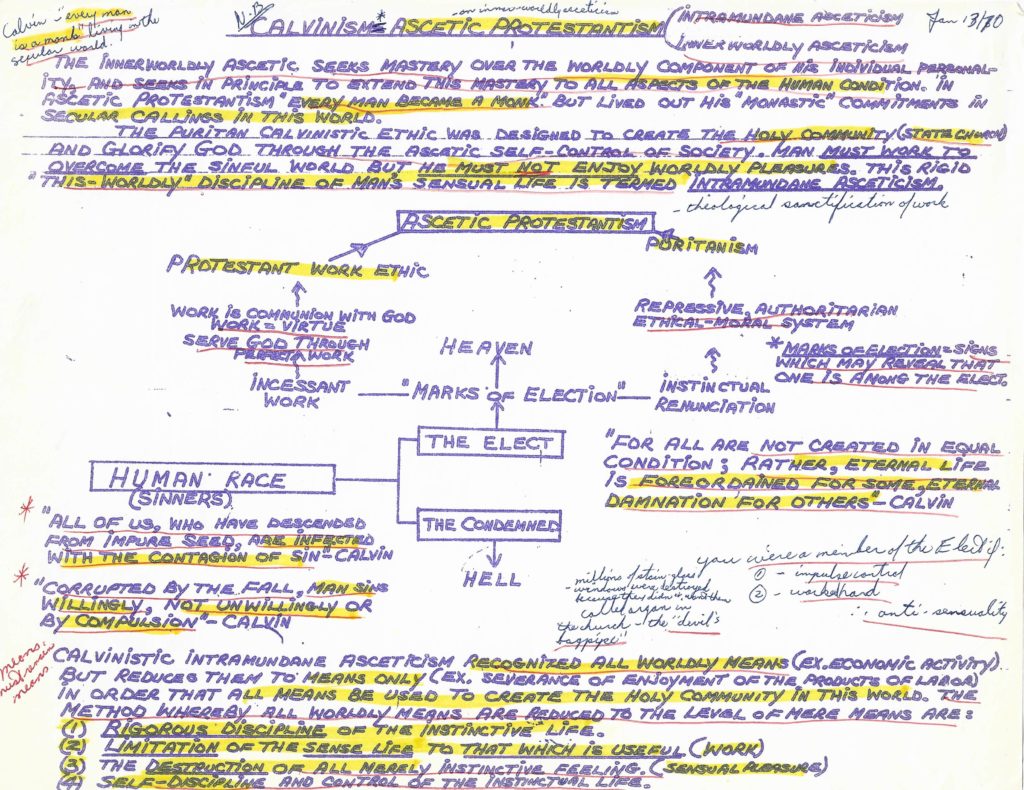

Jack’s dittos were always in blue ink; this one, typed (by a secretary – no professors typed at the time) – is typical of the kind of detail and focus on ideation or intellectual ideals inherent and/or developed in cultures. Even more representative of Jack’s thought and content-delivery process are these two diagramatic charts, the first one on Calvanism or Ascetic Protestantism…

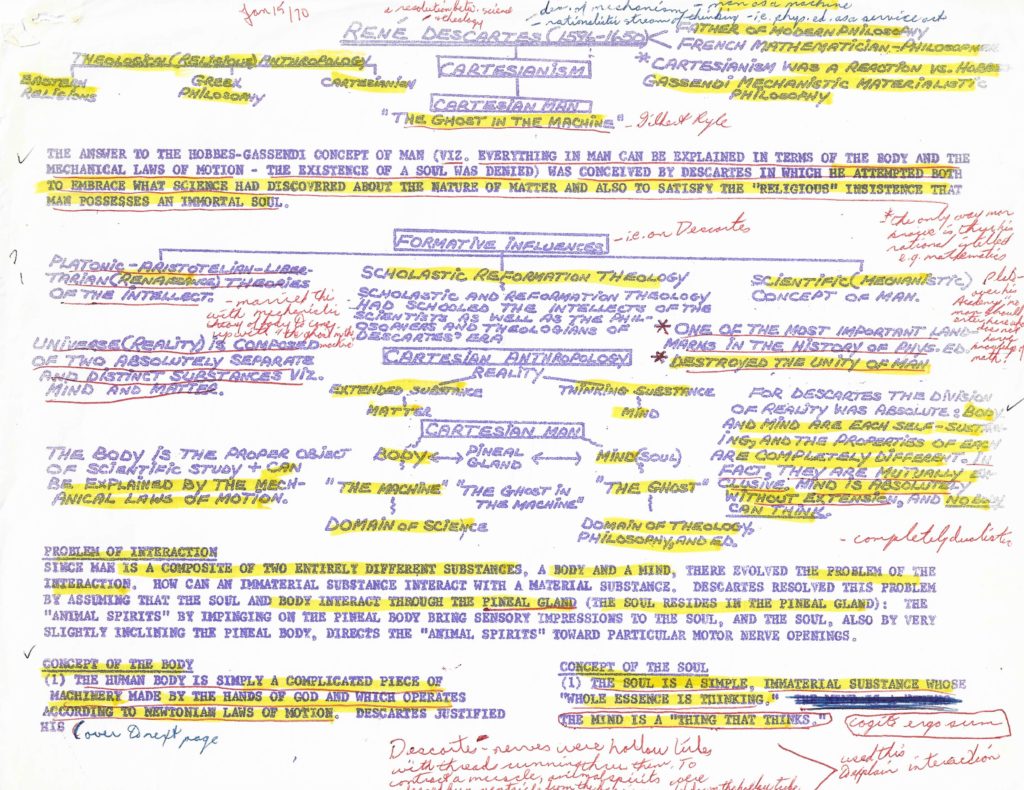

and this one on Cartesian dualism:

The inscribed notes are my scribblings. Growing up in the United Church, I was imbued with Protestantism as a system of belief. Like most Christian religions, Protestantism preached the doctrine of “original sin.” Humans were born into sin and needed to spend their lives constantly endeavouring to be ‘good’ by, for example “renouncing the flesh” (instinctual renunciation, as Jack called it), perceiving sensuality as evil, working very hard – the Protestant Work Ethic, itself a sanctification of work – in deference to play or being idle or enjoying bodily movement for its own sake. Personally, I just never bought the original sin Kool-Aid in my church’s teachings; very quickly, the Bible, especially its Old Testament became allegorical for me. How could anything my body did that brought so much pleasure in movement be deemed inherently evil. Years later, I imbibed – and eventually taught continuing education courses directly from – Catholic church excommunicated priest Matthew Fox’s eloquent book, Original Blessing; in it, the maverick theologian extols the sacredness of creation, its joy, our original blessing, the diametric opposite of original sin. Thus, Jack’s ascriptions to concepts like the Protestant credo about our need to gain “marks of election,” that is, doing good deeds, avoiding anything pleasure-ful from the senses actually were means to build up merit points/marks so that when your body died, you had a better chance of being elected to get into heaven. John Calvin was a French theologian and architect of the Protestant Reformation and that religion’s break from the Catholic Church. I liked Jack’s encapsulation of Calvin, “that dour and profoundly unhappy divine whose greatest fear was someone, somewhere might be having a good time.” Thus, Jack’s teachings were beacons enlightening what I believe I already knew. Certainly, the intellectual ideals he taught about Calvinistic and Protestant influences resonated deeply within me.

The second chart pertains to another formative French influencer, René Descartes, the “father” of modern philosophy. Cartesian dualism was and remains a profoundly impactful cultural ideal; its assertion is that the mind is completely separate from the body, mutually exlusive, without extension into either entity, as though humans are basically cut off at the neck.To this day, I remember Jack quoting educational historian, R Freeman Butts who stated, “we have come through 2000 years of higher education based on the notion that [hu]man[s] is[are] essentially a soul imprisoned for mysterious, accidental reasons in a body.” Butts’s assertion, to me, was profound and I still think of all manner of ways higher education enobles the mind over the body. Learning through the physical is a relatively recent product of the play and kindergarten movements, Montesssori schools, the leisure movement etc. Professional athletes, masters of their bodies’ functions are often demeaned as anti-intellectuals, “jocks” who operate in some kind of toyworld universe, quite separate from the “real” world of important work.

We looked at ancient cultures in Jack’s course, learning about cultural ideals from the pre-Christian Athenian Greeks – at least those in the aristocratic class (ancient Greece was a slave culture) – and their ideals and cocomitant practices such as

~ arete ~ or all-round development, of body, mind, and soul, exemplified in Greek educational systems that enobled learning of music, drama, arts, sports and exercise as on par with learning philosophy or any other academic subject; the ancient Olympics were religious festivals in which sport was merely one component;

~kalos kagathos ~ the ideal of beauty and goodness in all aspects of life, from art to sport to daily life; moderation in all things in life, or, nothing in excess;

~ eudaemonism ~ living the good or blessed or happy life.

Perhaps the most heralded phrase from ancient cultures is the well known, ‘a sound mind in a sound body’ (mens sana in corprore sano, as the Roman poet, Juvenal first coined the phrase), an ideal that epitomizes Jack’s teachings and one that became somewhat of a north star for PE/Kinesiology as a discipline. Jack was careful in his writings and teachings to note the origins and dualities of culture. For example, we spent considerable time learning about Plato and his diametrically opposite views of nature. Plato, Jack felt and revealed was often perceived as a founder and supporter of ideals enobling the body. For example, over the door of his Academy were inscribed these words, “let no one ignorant of geometry enter,” a clear endorsement of the mind. Plato purportedly also opined, “sweat is the doorstep to manly virtue,’ an accreditation to the physical body. He taught us about what he called the cultural action < > reaction mechanism, pendulum-like swings of belief like asceticism, that adherence to severe self discipline and avoidance of all forms of indulgence stemming from the Middle Ages, an ideal that rebounded into the more hedonistic Reformation and Renaissance ideals of beauty in art, education, and daily life. Books that Jack read and introduced to us – and they were legion in number – were often mind- and imagination-challenging just in their titles, as was G Rattray Taylor’s, Sex in History. If he deemed any work of writing to be particularly important, Jack would say, “it’s a dandy!” Some phrases he used were priceless; one religious zealot was said to have proclaimed, “syphillis was created to keep man’s nose to the grindstone.” Interestingly, in the whole course, not once did Jack mention an athlete or a sport or daily life example – his course was truly a history of ideals, ideologies, intellectual trends, and cultural shifts.

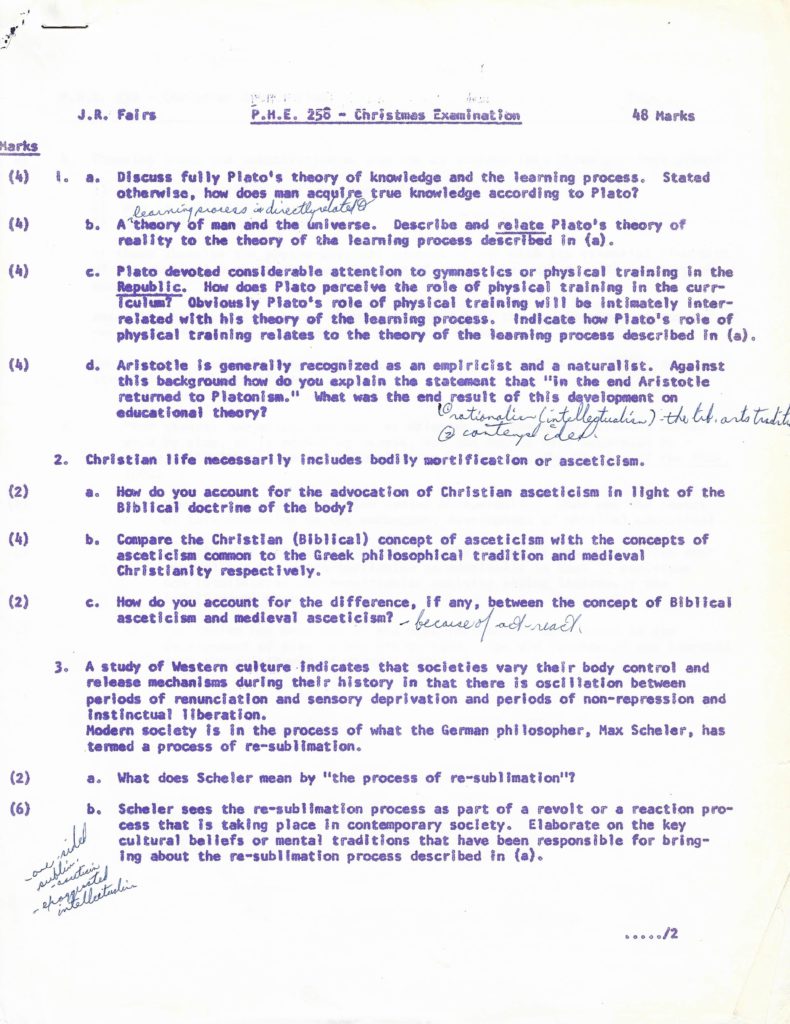

Jack’s tests and exams mirrored both his teaching style and course content; all were short-answer and essay style questions and he graded all exams, no teaching assistants were assigned at the time. A quick glance over his Christmas exam 1969 exemplifies his approach to the examination performance/learning process as well as the nature of his erudite approach to the subject matter:

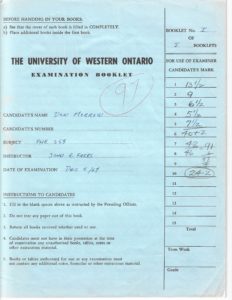

For me, exams in any course brought out my competitive nature, doing well was a challenge and in Jack’s course, I felt at-home with the content and I wanted to do well just because it was Jack. Apparently, I exemplified a good grasp of the material on that Christmas exam and I remember being quite proud of my grade:

In mentioning this blog to a friend and former class-mate, he said, “I remember Jack handing back an exam in class letting everyone know he had to send my exam over to the Med School ECG [electrocardiogram] readers to read my writing.” Apparently, my friend’s writing was so scrawled that Jack struggled to read it and couldn’t resist the Med School quip – vintage Jack Fairs in the classroom!

Jack wrote scholarly, in my view, very cultivated, theoretical, conceptual articles, mostly on ancient Greece ideals of the body – “When was the Golden Age of the Body?” was perhaps his most well known piece. And he wrote about the developement and role of athletics/sport in higher education. Mostly, he wrote for teaching, shunning academic conferences, devoting his energies to the classroom, to coaching the sports he loved, to spending time just talking with students and student-athletes. He was effervescent, always smiling, always jocular, and ever-masterful at instilling skills in his athletes. Jack co-taught an undergraduate and graduate course in Strategy and Tactics and I regret not taking the opportunity to sit in on some of those classes. What propelled me into pursuing a PhD in sport history was Jack’s P.H.E. 258 class, its content, and especially his teaching. I can’t begin to imagine the number of hours he spent in Western’s library, ferreting out the books from all manner of disciplines to build his course content. I do know that he had his library privileges suspended several times because he “forgot” to return books on time. Consequently, when we became collleagues, he borrowed my library card and other faculty members’ cards in his unrelenting quest for information, knowledge, and works that buttressed his beliefs about the history of the body/PE in western culture.

Jack’s impact on my career went well beyond him being one of my influential Undergraduate course profs. It was he who guided me toward doctoral work with Dr Peter Lindsay at the Unversity of Alberta and concomitantly encouraged me to read and study Robert F. Berkhofer Jr.’s brilliant book, A Behavioral Approach to Historial Analysis, probably the single most impactful book I have ever read (at least 10 times) and utilized during my career; he who took me aside early in my academic career to advise me strongly about the importance of publishing pre-tenure; he who defended and lauded my work in continuing appointments; he who wrote a marvellous letter supporting my case for tenure and promotion, among many other forms of professional and personal support. And still, I maintain Jack’s Undergraduate course teaching was the single most important determinant in my career choice and path. Jack retired from Western in the mid-1980s when mandatory retirement at age 65 was the law. In his late 90s now, still vivacious, still looking younger than he really is, still devoted to sport, John Russell Fairs remains one of the earliest intellectuals (possessing, as one friend put it, “a majesty of intellect”), ironically gifted in both mind and body, within the field of Physical Education/Kinesiology. Sometime in the late 1980s, I found the beautiful oak lectern piled unceremoniously in the garbage area of the Thames Hall loading dock. To me, it was the pulpit from which Jack taught me and others so much about culture, humanity, and the body. I retrieved it and for years, it sat in my office with a huge Merriam Webster dictionary resting on its surface, its pages open to the word ‘dualism,’ my way of honouring Jack. Often, so often, I tumble home to my memories of Jack, as coach, as mentor, and particularly as the intellectually gifted mentor-teacher he was and remains to me.

Addendum 31 August 2021

Jack Fairs died yesterday, having just celebrated his 98th birthday. I am so glad I was able to share this blog with Jack; his family read it to him just after I published it and Jack called me to thank me. We had such a lovely chat and he was as sharp as ever. I am privileged indeed to have known him and spent so much time with him, he as mentor, teacher, coach, colleague, and friend. The local London newspaper ran this memorial tribute to Jack. And former squash players on Jack’s teams made this picture/video slide-show tribute to Jack. What a delightful human being was Jack Fairs. This was his obituary as published in the Toronto Globe:

JOHN “JACK” RUSSELL FAIRS August 22, 1923 – August 30, 2021 Passed away peacefully, surrounded by his loving family, at University Hospital, in London, Ontario, on Monday, August 30, 2021. Survived by his loving wife of 60 years, Peigi; daughters, Nancie Fairs-Dickie (Ron), Kim Fairs-Cosens (Tony); and his son, John Fairs (Sally); grandchildren: Scott Dickie (Cassidy), Marshall (Kristen) and Kelsey Cosens, Jack Jr. and Andrew Fairs; and great-grandson, Zander Dickie. Jack attended the University of Western Ontario and graduated with an Honours Chemistry degree. After attending Columbia University in the City of New York for his master’s degree, Jack returned to London to help establish the newly formed PHRE at UWO, and fulfill his passion to teach and coach. Jack retired from teaching in 1989, and coaching in 2003. Funeral arrangements are being made for a private family service with a larger Celebration of Life to take place at a later date. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to Western University – Men’s Squash Team, ensuring Jack’s legacy continues.

Jack’s hometown newspaper , The London Free Press was a bit more effusive in its tribute to him after listing his surviving family members:

A native of Tillsonburg, Ontario, Jack was a naturally gifted, self-taught athlete. His lack of ever having a coach or mentor growing up led to and kindled his desire to fill this void for others, especially in tennis and baseball in London and Chatham. Jack attended the University of Western Ontario and graduated with an Honours Chemistry degree. At this time, there was no faculty of Physical Education at Western. After attending Columbia University in the City of New York for his master’s degree, Jack returned to London to help establish the newly formed PHRE at UWO, and fulfill his passion to teach and coach hence his designation as an “original builder.” This led to a lifetime of teaching, coaching and mentoring until he retired from teaching in 1989, and coaching in 2003. Jack never really retired, spending his Professor Emeritus years continuing to coach and mentor his successor(s). In true “Jack” fashion he would want everyone to celebrate his legacy, rather than mourn his passing. Funeral arrangements are being made for a private family service with a larger Celebration of Life to take place at a later date. Special thanks to all the doctors, nurses and PSWs at University, Victoria and Parkwood Hospitals. In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to Western University – Men’s Squash Team, ensuring Jack’s legacy continues. “Somewhere in your busy lives’ journey, I hope you consider expanding your experiences through a commitment to others in a way that suits your special needs and talents. You will feel most fully alive and will come to be your Best Self when you are working with others for the sake of a shared ideal” – Jack Fairs