44 X 20: Pickler, Pickled…

Over the last 4 years, I have become smitten, enchanted by a court sport, pickleball. Elsewhere in my blogs (here), I have traced my immersion in and involvement with court sports throughout my life. In this entry, I want to attempt to express what it is – in its totality and in my sense of plentitude – that captures a human – me – in a web of interest seemingly far out of proportion to the activity itself. As I think about how to put a vocabulary to something that is best experienced rather than described in words, I am reminded of essayist William Hazlitt’s profound 1828 tribute to the fives’ (handball was called fives at the time – presumably five fingers of the hand) player, John Cavanagh. Hazlitt had a fascination with what he called mechanical (versus intellectual) excellence and in his essay (full essay here), he delves into his observations about unparalleled skills of jugglers, tight-rope walkers, and the 18th/19th centuries fives’ aficionado, Mr. Cavanagh. The gist of the latter tribute I have quoted below, verbatim:

It is not likely that any one will now see the game of fives played in its perfection for many years to come – for Cavanagh is dead, and has not left his peer behind him. It may be said that there are things of more importance than striking a ball against a wall – there are things indeed which make more noise and do as little good, such as making war and peace, making speeches and answering them, making verses and blotting them; making money and throwing it away. But the game of fives is what no one despises who has ever played at it. It is the finest exercise for the body, and the best relaxation for the mind. The Roman poet said that “Care mounted behind the horseman and stuck to his skirts.” But this remark would not have applied to the fives-player. He who takes to playing at fives is twice young. He feels neither the past nor future “in the instant.” Debts, taxes, “domestic treason, foreign levy, nothing can touch him further.” He has no other wish, no other thought, from the moment the game begins, but that of striking the ball, of placing it, of making it! This Cavanagh was sure to do. Whenever he touched the ball, there was an end of the chase. His eye was certain, his hand fatal, his presence of mind complete. He could do what he pleased, and he always knew exactly what to do. He saw the whole game, and played it; took instant advantage of his adversary’s weakness, and recovered balls, as if by a miracle and from sudden thought, that every one gave for lost. He had equal power and skill, quickness, and judgment. He could either out-wit his antagonist by finesse, or beat him by main strength. Sometimes, when he seemed preparing to send the ball with the full swing of his arm, would by a slight turn of his wrist drop it within an inch of the line. In general, the ball came from his hand, as if from a racket, in a straight horizontal line; so that it was in vain to attempt to overtake or stop it. As it was said of a great orator that he never was at loss for a word, and for the properest word, so Cavanagh always could tell the degree of force necessary to be given to a ball, and the precise direction in which it should be sent. He did his work with greatest ease; never took more pains than was necessary; and while others were fagging themselves to death, was as cool and collected as if he had just entered the court. His style of play was as remarkable as his power of execution. He had no affectation, no trifling.

To me, the praise for and discernment into Cavanagh’s singular prowess is so deft and so insightful about the genius of one person’s immersion in a physical game, in this case, handball. I am certain there are equally apt descriptions of what it’s like to be a skilled musician or artist or trades-person, architect, chess-player, chef etc. What I want to do here, using words and images is to express my magnetic fascination with one modern court-game, pickleball. And in full transparency – I am nowhere near the level of physical skill of the ‘cavanaghs’ of any activity. The lens I bring is more from the inside of a player of a court game rather than Hazlitt’s outside-the-game perspective on one highly skilled athlete’s prowess in the game. Perhaps Hazlitt himself played fives, I don’t know; he seems more in kind of hyperbolic awe of Cavanagh. For myself, I am a relatively adept athlete who loves to play sports, particularly court sports. Further, my lure to the game is all-encompassing, that is, the court, its geometry, nuances of shots, decision-making, strategies, and so forth. Skill or skill-striving in playing the game is but one ingredient of my pickleball enchantment.

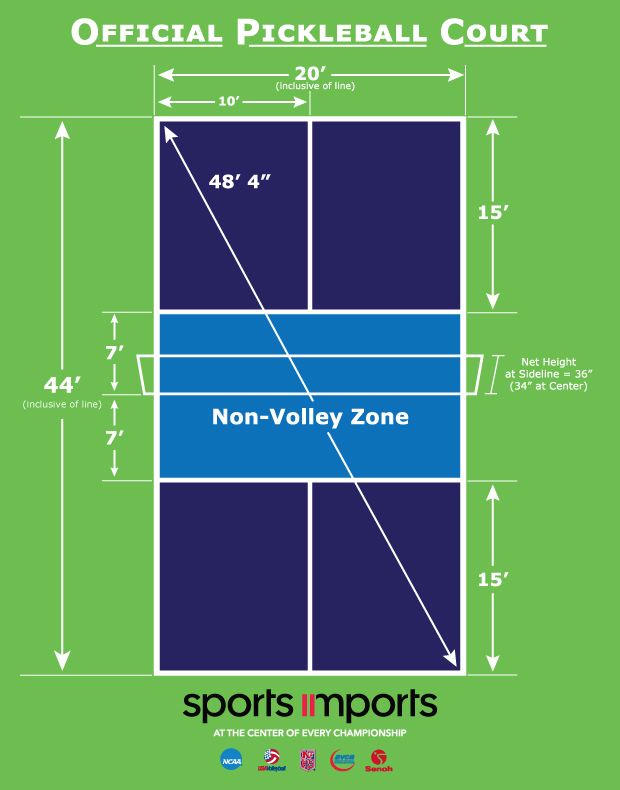

Some contextual information about the nature of pickleball – I’ll use PB and pickleball interchangeably – is an important prerequisite to describing my passion for the game. I’ll start with the court. The outside dimensions of the full playing area are 44 feet long by 20 feet wide, exactly the dimensions of a doubles’ badminton court (coincidence? I think not). By far, badminton was the court sport I played most often and the place I felt most at-home, for lack of a better expression. Though the badminton singles’ court is 17 by 44 feet, I think I am accustomed to that playing area in both badminton and pickleball; I believe I have a feel for playing racket sports in that spatial domain. Below is a schematic of the court showing all of its measurements, an important visual representation for my later discussion around the geography of the game itself:

Here is a bird’s eye view of an actual outdoor pickleball court:

I know not where this court is located but it is good depiction of the court and I love its name, “Wee Tri Court.” There are some basic things to know about the court to understand the game. In the photo above, the green area extends 7-feet from the net (on each side) toward the back of both sides of the court and that area is formally termed the non-volley zone but more commonly called the kitchen. The best explanation for the culinary attributive term is that it is taken from outdoor shuffleboard wherein the kitchen is the area behind the primary scoring zones; if your shuffleboard disc lands and remains in the kitchen, it is a deduction or penalty of 10 points. In pickleball, when you are about to hit a ball coming over the net, you cannot step into or have any part of your body physically touching the kitchen unless the ball bounces in the kitchen first, then you can step into the kitchen but only to play the ball that landed there, then you must step back out of the kitchen. The pickleball penalty for stepping on any part of the kitchen including the boundary lines around that area while striking the ball is loss of the point or loss of serve, depending on who served during the particular point or rally when the spatial transgression occurred.

From my experience, the kitchen is what makes pickleball so interesting to play; it is the geographical genius of the game. Its presence and impact lurks on every point. Unlike in tennis, players cannot stand right at the net to volley or cut shots off from their opponents. Most of the game, at least the most ‘touch’ shots in the game are played with opponents standing right at the 7-foot line hitting short drop or ‘dink’ shots just over the net toward the kitchen area or just beyond that territory. Aptly termed dinking or the dink game (in reality, short, well-placed, low-bounce drop shots), it demands patience in manoeuvring opponents laterally, mostly, thereby trying to force an error on their part, that is, hitting a dink shot into the net or outside the court boundary or too high over the net such that your opponent can smash the ball right at you or down toward your feet.

Pickleball can be played as singles, doubles, and cut-throat (3 players on the court) although competitive events are only in singles or doubles. In the outdoor court image above, the 4 blue quadrants are the service courts. Compare their location to tennis where the service courts extend from the net and end about 2/3 of the way into each half of the court. In PB, the service court area starts at the 7-foot line of the kitchen and extends to the baseline. To serve, the person has to be standing completely behind their own baseline and must serve underhand with no part of the paddle edge above their wrist line and ball contact below the hips.The general or basic idea behind the serve is to put the ball in play to start a rally although at higher levels of play and skill, players can hit with considerable pace and put spin on the ball all in efforts to force an error or weak return on the part of their opponent. My main point is that the PB serve is not the offensive weapon of sheer power as it is in tennis.

Before going into the feel of the game, its nuances, variations etc., I want to show a few pickleball court examples of what cultural geographer Karl Raitz calls the landscape ensembles of sport. The most definitive example I can conjure of a sporting “landscape ensemble” is hole #12 at the Augusta National golf course in Atlanta, Georgia, home of the annual Masters’ professional golf tournament:

The sheer beauty of this golf hole is incredible and so visible and palpable even if only viewed on television – it must be even more magnificent when experienced live. Almost any hole at Augusta could be selected to typify how much landscape surrounds and shapes play in this sport. There is history, prestige, and all kinds of meanings attached to, in this case, the Masters’ golf holes. I suspect players and spectators appreciate the beauty of the golf course and yet the seemingly incongruous goal of putting a tiny white ball in a very small hole with as few strokes as possible, with all manner of hindrances like sand-traps, trees, ponds or lakes – what some sport philosophers call a ‘willing suspension to unnecessary obstacles‘ that is just accepted in sport – is more or less subsumed within the landscape; the object of the tournament – to win – is enshrouded in the landscape. And, the televised-familiar Masters’ logo of a golf flag embedded at Atlanta’s location on a yellow US map (copyrighted logo so I can’t insert it here…just a link, subtle golf-term pun intended) is in itself a landscape replica as is the soft, almost mystical music played frequently during the tournament’s 4-day broadcasts, the latter uninterrupted by commercials. In passing, I have run the 18 holes of many golf courses, in many countries (including the famed St Andrews’ course in Scotland) as marathon training runs in the early dawn hours before golfers arrived at the links. The manicured softness of dew-dappled fairways often, at that time of day, littered with an orgasm of flat, circular spider webs and ground contours felt on my running feet were a welcome contrast to the paved roads of most of my longer runs.

The same can be said of a legion of sporting venues, all landscape ensembles that both encase and transcend the sports played at these venues. Some examples – Lord’s Cricket grounds in St. John’s Wood, London, England; Fenway Park (baseball), Boston with its Green Monster outfield wall; Wimbledon tennis grounds or Stade Roland Garros home of the French Open in tennis; the Rungrado 1st of May Stadium in Pyongyang, North Korea, the largest spectator-capacity (150,000) stadium in the world and therefore a profound ensemble just by virtue of its size; even the streets of Pamplona where the running of the bulls occurs annually during July – as repulsive as the concept is to me – has it landscape ambiance. And spectators too are a huge part of the landscape ensemble. I think of attending a University of Michigan football game in its 107,000-seat stadium and the tailgate parties and the Michigan fans decked out in their distinctive maize and blue colours, all an ensemble of meaning and pageantry and tradition and the game. When I ran the Boston marathon a few times in the 1980s (always held the 3rd Monday in April, Patriots’ Day in the city) the one million plus spectators strung out all along the 42 km route contributed immensely to the event as did the subtle whiffs of the Spring-blooming cherry blossom trees. At the same time, there are many stadia that are little more, in my opinion, than concrete doughnuts, devoid of any aesthetic component, more of a commercial container with meanings brought mostly by their fans. And the fondness for or familiarity toward any sporting venue doesn’t have to be attached to famous locales like the examples cited above. Often, our earliest gymnasia or arena – for me, the original indoor ice-rink in Exeter and even the river swimming hole in that town – or baseball diamond can have the same attachment of feeling, even an aesthetic sense just from playing, moving, and/or spectating in these spaces.

More and more, I experience the kind of understated elegance of PB courts. In its own right, 44 X 22-feet divided by a net 36 inches high at the posts and 34 inches high in the centre, is just a deserted pad, concrete, wood (see my note below re playing on wood-floor courts), and other surfaces, almost one-dimensional at first blush. And then you/I play and the game and people bring the court’s flatness into bold, more than 3 dimensional relief – almost reminiscent of cardboard pop-up features in children’s books. I want to display a few actual court images to add visual meaning to my lure to these places. My preference is to play on outdoor courts, likely, I think because during the ongoing pandemic for the last 3 years, it was safer to play/be outdoors than mingling with people in indoor facilities. And my hip osteoarthritis and full hip replacement surgery (for a description/story of the latter, see my Cycologist blog here) kept me off any PB court for 14-15 months during the ongoing pandemic. Back to landscape ensembles and pickleball courts, here is an outdoor court example:

I can almost feel its autumnal splendour and allure. My favourite court, bar none, indoors or outdoors, is this one:

This court is located at the home of Jacques Roy who lives in Talbotville, about a 25-minute commute from my home in Komoka. It is just so well constructed and the playing surface, colours, and arboreal, meadow-like surroundings combine to make it a superb facility. Roy, a former professional baseball player, constructed the court on his property circa 2019. It is Roy-described and surface-labelled as “King’s court,” with the ‘o’ in court cleverly stylized as a pickleball…

I’m not certain of the royal label, perhaps an Arthurian legend allusion but reminiscent to me of Eddie “The King” Feigner, famed softball pitcher who played over 10,000 games absolutely dominating full teams with his traveling 4-person team, The King and his Court (Jacques is a very skilled PB player). Maybe it’s just a self-attribute Jacques uses to add a character-stamp to his realm. In point of fact, Jacques just read this blog and shared that as a French Canadian, his last name – Roy – is fairly close to the French word ‘roi,’ meaning king – hence a one-letter play on the word to name the King’s Court. Lighted for night-play and equipped with shaded benches, the net is perfectly suspended and affixed – see the metal plate at the post above – to the court surface by my friend Peter Singleton’s son. Jacques insists that all players prior to using the court sign a waiver for liability reasons. He charges no fee and it seems as long as he knows your name and you play for fun, anyone can play on the King’s court:

Often, I have used the court just for self-practice with my ball machine (more on that little gem below) and and plethora of pickleballs:

Closer to home, I utilize outdoor tennis court facilities a lot. These courts – in Kilworth, Komoka, and Delaware – are public tennis courts maintained by the municipality. Within the last few years, pickleball court lines have been superimposed on the tennis courts. For example, here is a court at the Komoka Community Centre:

The PB lines are in yellow, tennis in white. For size comparisons, note that the PB baselines are just a little bit, maybe a foot longer than the white, rear service line on the tennis court. Tennis nets are just 2 inches higher in the centre than pickleball nets so they are relatively the same; at the very least, the extra height adds an adaptive challenge when doing dink shots on a tennis court. On such public courts, the kitchen is only marked by boundary lines, not coloured differently as the area is on specialized, pickleball-only courts. Again, this isn’t much of an issue to most players because it’s the 7-foot line that is ingrained in players’ awareness. The court where I often play and practice the most is in the park in Kilworth, 4 blocks from my home:

Resurfaced in the Summer of 2022, the blue-painted concrete provides great, visible contrast for the white tennis and yellow PB lines. The photo above was taken in December 2022 when the tennis nets had been removed for winter storage. I was able to bring my own net and set it to the correct centre- and post-heights. The newest courts – completed in 2022 – close to my home are the 2 courts in Mt Brydges, just behind the Legion. The surface was asphalt and the kitchen was not coloured distinctly but they were well built even if not a lot of space behind each baseline:

Recently, in July 2023, the Mt Brydges’ courts were resurfaced, texturized, and painted with a slightly different hue of blue in the non volley zones:

Although the two courts there slope decidedly from east to west (from the school end to the grass adjacent to the parking lot), they are great for playing and relatively undiscovered re use. In the Fall of 2024, we had a unique sun profile just south of these Mt Brydges’ courts:

Two other venues have served – another pun intended – me well re getting lessons from very skilled pickleball coaches. I go to these courts in St Thomas to work with Carolyn, an incredibly gifted PB player (5.0 ranking) and coach (the shaded court, lower right is my favourite in the hot summer months):

This facility was built about 5 years ago and features 8 PB and 8 tennis courts located within Pinafore Park. Sadly, the PB court foundations were not well laid such that most of the kitchen areas werecracking in the concrete, not dangerous or interfering with true ball bounce yet; in the summer of 2023, the municipality resurfaced the courts and there was some talk of ‘doming’ them to make them accessible all year (hasn’t come to fruition yet). This court level view gives a better perspective of the Pinafore courts at surface level, a court-scape ensemble:

Recently as well, the London Hunt and Country Club (private, primarily golf club (tennis as well) installed 6 pickleball courts, complete with windscreens on the perimeter fencing (common on public courts too) and the first I’ve seen with a wind-sock enabling players to gauge wind direction and velocity:

The other instructional, outdoor court facility I have utilized is located at the Dorchester Community Park, about a 35-minute drive from home. At one time, one of three outdoor tennis courts, the westernmost court was seconded to create 2 PB courts. These courts are back-to-back with a chain-link fence separating and surrounding the courts:

The other instructional, outdoor court facility I have utilized is located at the Dorchester Community Park, about a 35-minute drive from home. At one time, one of three outdoor tennis courts, the westernmost court was seconded to create 2 PB courts. These courts are back-to-back with a chain-link fence separating and surrounding the courts:

They have been reasonably well kempt, although a surface crack on the side of one court is becoming an issue. What makes the Dorchester courts so appealing is that on the western side there is a huge grove or double row of very tall evergreen trees running the length of the two courts. Wind is the enemy of outdoor pickleball play or practice because the plastic PB ball is so light, it is dramatically impacted by any noticeable wind. In my view, windy conditions are the same for all players; we switch ends every game so wind is just another challenge, I believe. On these Dorchester courts, the prevailing westerly wind is, for the most part, blocked by the trees. This is the court-of-choice for outdoor lessons from one of the best teachers I have encountered in any racket sport, Ralph Hackbarth.

Indoor, specialized PB facilities are relatively rare. Most community groups use gymnasia with all kinds of intersecting court markings – badminton, basketball, volleyball, pickleball etc – lining the wooden floors. Wood floors are kind of okay for PB; however, the ball can spin or skid unpredictably a lot more; window lighting can make it difficult, at times, to track the ball or determine if a ball landed inside or outside the court boundaries; and often, PB court baselines are quite close to the gym walls. We are very fortunate to have a superb, 8-court facility at the Greenhills Country Club (golf, tennis, and pickleball) located in Lambeth, a 15-minute commute from our home. Renovated in December 2022, here are the PB courts at Greenhills:

The only difference, to date, in recreational versus competitive courts are the stands for spectators:

And the professional game is spreading very rapidly in North America with the Professional Pickleball Association (PPA) and the very new Major League Pickleball or National Pickleball League with 24 sponsored teams and 96 players competing for a total of 5 million dollars; games are played most commonly outdoors in Arizona, California, Florida, and Georgia. There are two global organizations governing the sport, the International Pickleball Federation and the World Pickleball Federation. The pro game is in its infancy with average annual salaries of $47,500 US; equipment company sponsorship, demonstration events, and pro pickleball vacation packages (big name players, like Ben Johns, touted as the world’s best male player, host PB players in vacation locations like Croatia, Costa Rica etc through companies like Pickleball Getaways). Ben, his brother, Collin (also his doubles’ playing partner), and two other pros run Pickleball 360, a online site that features over 140 instructional videos available for a monthly subscription fee. I subscribe to a Spotify PB podcast called Pickleball Tips – 4.0 to Pro that features regular tips geared to my playing level. Professional tournaments’ videos are widely available on sites like youtube – a recent mixed doubles’ finals can be seen here.

And the professional game is spreading very rapidly in North America with the Professional Pickleball Association (PPA) and the very new Major League Pickleball or National Pickleball League with 24 sponsored teams and 96 players competing for a total of 5 million dollars; games are played most commonly outdoors in Arizona, California, Florida, and Georgia. There are two global organizations governing the sport, the International Pickleball Federation and the World Pickleball Federation. The pro game is in its infancy with average annual salaries of $47,500 US; equipment company sponsorship, demonstration events, and pro pickleball vacation packages (big name players, like Ben Johns, touted as the world’s best male player, host PB players in vacation locations like Croatia, Costa Rica etc through companies like Pickleball Getaways). Ben, his brother, Collin (also his doubles’ playing partner), and two other pros run Pickleball 360, a online site that features over 140 instructional videos available for a monthly subscription fee. I subscribe to a Spotify PB podcast called Pickleball Tips – 4.0 to Pro that features regular tips geared to my playing level. Professional tournaments’ videos are widely available on sites like youtube – a recent mixed doubles’ finals can be seen here.

In passing, one of the female players in the latter video is Anna Leigh Waters, currently, at 16 years of age regarded as the best female player in the sport. My main point about the pro PB game is that it is both a reflector of PB popularity and a key variable in the growth and dispersion of the game. It remains to be seen if live televised games will attract a significant audience; broadcasters of the pro games gradually are becoming more adept although currently, they spend a lot of time explaining basics of the game because it is so new and the audiences’ knowledge of the game might be very limited. At the same time, the quality of the visual broadcasts, for the most part, are superb in terms of being able to watch the game up-close, or see shot replays etc. The inevitable commercialization of the game is resplendent in the image of the currently ongoing 2023 US Open 7th annual championships below. Notice the ubiquitous sponsor signage on the court perimeter…

Some professional courts even feature large projection screens at the back of each end of the court, ones that can electronically blast out font-stylized messages like ‘WOW’ when a player hits a great shot. Such spectator-focused screens are common in stadiums and arenas in professional team sports. Personally, I think the signs and screens create a less than desirable landscape ensemble for the sport and yet, understandably, paying sponsors want their ads highly visible.

There are some 37 million pickleball players in the US alone, with 10,000 courts. In Canada, there are about a million active PB players, by some estimates this represents a 3-fold increase in just over a year. Devout players in Canada have to find community centres, churches, schools, and other venues during colder months whereas the southern states’ climate fosters year-round outdoor play. The vaunted title of pickleball capital of the world belongs to Naples, Florida where the East Naples Community Park boasts 60 outdoor courts with lights:

The southern US has a great number of multi-court, PB facilities like the one depicted at the SaddleBrooke Ranch – a 55+ contained community – located just north of Tuscon, Arizona:

Having year-round access to such facilities makes me salivate mentally. I know many players in Canada who travel to Florida, Arizona, and other states just to be able to play during Canadian winters.

My first taste of PB was about 5 years ago when I encountered Marcia, the wife of one of my Undergraduate classmate’s at a funeral reception, of all places. When I asked her about John and how he was doing, she responded, “he spends most of his time playing pickleball.” My response was, “what’s pickleball?” and her elegant response was an invitation to try it, with John’s help, at the gymnasium inside the Carling Heights Optimist Community Centre. Fittingly for me, the Centre is located on the site of the former Woselely Barracks’ gymnasium building. At one time, actually for many decades, the Barracks was a very active Canadian Forces’ base and is now a designated federal heritage building and a park area. Congruously then, I remember thinking, the Carling facility is the current iteration of one of the finest gyms (the one contained within the Wolseley Barracks’ grounds) in which I played badminton. What made Wolseley outstanding was its superb condition and the extraordinary height of the gym space. For singles’ badminton players, a high ceiling is a spatial nirvana for hitting lofty, arcing serves and deep, baseline-to-baseline “clear” shots. I practised at Wolseley quite often during my high school and university badminton-playing days. Thus, it was a kind of coming home to a remembered landscape ensemble in going to Carling to learn and play PB.

Reminiscent of my paddle-ball experiences in university and even my earliest wooden-paddle game experiences in high school (played as a singles’ game against a brick gym wall in noon-hour, intramural sport at Beck Collegiate), the game enchanted me almost immediately. John was a great teacher and the varied skill levels of the Carling players as well as their good-natured and welcoming affability were also drawing cards that lured me to play at Carling at least once a week. Occasionally, I played closer to home, in the 3-court gym at the Komoka Wellness Centre. Within my first year, I started playing at Total Tennis or what it is now called, Greenhills (see the indoor court image earlier in this blog). At the time, the Total Tennis facility was primarily one devoted to tennis but each tennis court could be converted to two PB courts by portable nets with pickleball court lines added to the tennis boundaries. The floor then and now is more like outdoor tennis courts and with no wind and the dark green walls as background contrast (no windows in the court area), it offered so much more consistency of play. Moreover, there were instructional clinics offered for every level of playing skill and I took advantage of those clinics and their excellent coaches. When Covid descended on the world early in 2020, I stopped playing indoors anywhere but maintained my annual membership at Total Tennis throughout the pandemic harbouring hope that its end or diminished impact would permit me to return.

My Covid and hip issue PB adaptations were many and varied. At first, in the Spring of 2020, I bought a 4 X 8 piece of 3/4 inch plywood, marked the net height on the board with bright red and weatherproof Tuck Tape and set it up vertically outdoors in front of my office window; there was enough space on the cement patio beside our hot tub to practice dink shots and even short service shots. Our neighbours got quite a kick out this slightly quirky activity. My interest in the sterile board-game waned quickly and I took to purchasing a few dozen pickleballs and a portable ball-carrier, the metal, basket-like device in this image:

The ball-carrier holds about 50 pickleballs and it is designed such that the legs can be swung upward 180 degrees so that the basket is at the bottom and the base of the basket’s cross-pieces are just far enough apart to be able to fit above one ball, then with downward pressure applied, the ball can be popped gently into the basket. As my hip became more and more painful, the basket’s ball-retrieval feature was so attractive. Alas, it turns out the basket was really designed for tennis and tennis balls compress and re-expand much more easily than plastic pickleballs and I found the balls were actually becoming mis-shapen by the pick-up process. I switched to buying and using a more efficient pickleball caddy (below) that does pick up balls easily, has wheels etc:

About the only thing I was able to do on the outdoor courts was work on serving and I could kind of self-set a ball within the court and hit to target areas – like the kitchen – for practice. However, my ability to do those simple shots became problematic pre-surgery. By mid-Summer of 2021, I could not even serve from a standing position because the very subtle shift or weight transfer hurt too much.

For most of the Spring, Summer, and Fall of 2020, my only live contact with other players was confined to taking lessons from Ralph Hackbarth at the Dorchester courts. As I mentioned above, Ralph is a superb athlete and coach. Doing drills and skills with him really increased my own skill level. What I lost in the process was transferring that learning into games. Like most sports or any skill learning activity of any kind, it’s very different learning and practicing skills without transitioning or bringing those skills into performance or game situations. That said, my lessons with Ralph kept me on the court safely from increased risks of Covid infection.

By early Fall 2021, I had to stop all pickleball activities; I could barely walk, let alone do ball skills with any kind of weight-bearing on my left leg. By the Spring of 2022, some six months after full, artificial hip replacement, I was back on my outdoor courts. I was able to secure a couple of friends – Sharon (Bucky, among her friends) and Veronica – who would do drills with me with all of us masked and/or maintaining careful social-distancing on the courts. One person, Brian Huston that I met before the pandemic at Total Tennis, has a penchant for inventions. He solved the tedious multi-ball retrieval process by using and adapting a 10-foot piece of 3-inches in diameter PVC (polyvinyl chloride, basically thick plastic tubing utilized mostly in plumbing applications) pipe. Brian cut his to a 6-foot length and I took his idea and design to make my own ball picker upper but I cut it to 7 feet (having measured its pending fit into our RAV4 vehicle). Using the 3-foot section, I cut off a half inch piece, subdivided it into 3 smaller pieces and took 2 of those pieces and affixed them inside the circumference of the ball retrieval end using PVC/ABS glue. Those little pieces make the opening just the right size such that when one pushes down on the pipe over a pickle ball, the ball is gently forced inside – without compressing the ball very much – and the balls cannot fall back out that end. Here is the just-finished product in our garage:

In tribute to Brian, I labelled it The Huston, in my inept but best handwritten script…

And I affixed an old suitcase strap to the pipe as a carrying handle. Unlike Brian’s, I selected PVC pipe with small holes – see the images below – which means I can see into the pipe as I retrieve balls to gauge how full the picker upper becomes; mine holds about 26 balls before I have to dump it out from the top end into my caddy (using the Huston is faster than the caddy for retrieval) or ball machine. A few months later, Brian contacted me with a modification idea. On hardwood floors or on special outdoor court surfaces like Jacques’ court, the PVC pipe end could scratch or mar the surface/flooring. So, with his instructions in-hand, I bought a 3-inch rubber coupler, adapted the diameter of the ball pick-up end of pipe itself and then affixed the rubber piece with PVC glue to the end, slightly overhanging the rubber edge beyond the pipe edge. To secure the rubber piece, we used a metal band-clamp. Here is the finished product viewed from the pick-up end:

And, from the side, you can see the PVC pipe holes that facilitate determining when the picker upper reaches full capacity of balls.

The Huston works amazingly well; it’s a bit heavy but for the number of balls I use for doing drills etc, it is terrific. There are commercially available light, transparent ball picker uppers but they are expensive – $80 compared to a grand total of $35 for my Huston – and they only hold about a dozen balls.

For almost 3 years, equipment loaded, I travelled to any outdoor court I could – even to Foxfield District Park located on Sunningdale Road north of my home. These 2 courts are great in that the nets stay up year round; however, there is no shade or wind protection so they tend to be anathema to my solo drills and skills’ sessions unless there is little wind and milder temperatures; however, unlike any other courts I’ve used, there is a large backboard on the baseline fence of one of the tennis courts – great for doing solo, rebound drills. Here is our RAV4 loaded and ready for any PB outing:

The cylindrical, open end of The Huston can be seen near the top right, one of its holes hooked (to prevent unwanted, potentially dangerous movement) by a short bungee cord to a metal clip affixed to the RAV. On the left, in the box is my collection of Franklin outdoor pickleballs, some 120 of them contained in the box and in the wire ball carrier just visible behind the box. My trusty back-pack containing my rackets, towel, arm-sleeves for sun-protection, sunscreen, water or G2 bottle, hand-sanitizer, wrist-bands, hat, carabiner clip for hanging the bag on chain-link fences, and small metal pill-cylinder containing 4, 300-mg aspirin tablets is leaning on the ball-box. The aspirin pills I carry because many of the folks with whom I drill or play are, like myself, seniors and aspirin is well documented for administering to anyone experiencing heart attack symptoms while awaiting medical attention.

In the centre of the image is my ball machine, brand-name, Pickleball Tutor Plus. Coach Carolyn introduced me to PB ball machines at the St Thomas courts. At the time, mid-Summer 2022, she was experiencing some hip problems and brought the machine to use as a teaching tool feeding me balls rather than she doing so. For some reason, I had pictured ball machines in any sport as larger and with some kind of tube out of which balls would be flung in an arc, kind of catapult style. Having used Carolyn’s machine, I decided to purchase one because I spend so much time alone on courts that the machine could and would serve (literally) me well. Turned out the best price – they are not cheap, about $2000.00 – was through Pickleball Depot with two stores in Kelowna and Vernon, British Columbia. At the time, Summer of 2022, both my coaches, Carolyn and Ralph were about to leave for vacations so I would be without them for at least a couple of months. Within 5 days of ordering it, my machine was delivered, free of shipping charges, to our home. I decided that my Tutor Plus needed a distinctive name in becoming my artificial tutor. Given Ralph had worked with me for years, my machine became The Ralph (see the image of the so-named machine in the back of our RAV4 above) both in honour of and tribute to his pedagogical prowess – Ralph is a master game strategist and he ‘sees’ the court and player positions with incredible acumen – and to remind me how fortunate I am to be able to have such a device in learning this magnificent game. In addition, I was pretty sure it wouldn’t be long before I was speaking to it and/or calling it other names when I mis-hit balls ejected from my mechanical tutor.

The Ralph looks larger in the RAV than it does on court:

One of my paddles is leaning on the machine with the device loaded with about 100 pickleballs. The wheels on the lower right are for ease of transportation with a front handle, The Ralph can be towed to the court. Underneath the machine, raising the whole box about an inch off the ground is a metal disc about 5-inches in diameter. That disc permits the machine to pivot, turntable-like via a button the control panel:

When the machine is turned on at the Power switch, on the top of the machine, another metal tray with four holes – somewhat resembling a poached egg tray – each hole slightly bigger than a PB ball spins counterclockwise slowly, each hole containing one pickleball. When one of the holes aligns with the open space in the machine, the ball drops into the machine to be spun and propelled out of the front while the 4-holed tray continues its orbit with a new ball dropping into the empty hole. In the image below, you can see the black tray with the visible holes and in the bottom right, a very sharp ulu-like fixed piece of metal that coaxes the ball into the drop-hole:

From the front as I would face the machine on the other side of the PB net…

It’s quite ingenious. The two visible wheels have a kind of sandpaper-grip finish by which they grip the ball as it descends into the cabinet and then spins the ball out the rectangular opening. On the control panel (above) I can ‘tell’ the machine to turn the wheels such that the ball will have either topspin or backspin. The elevation button is used to adjust the trajectory and distance of the delivered ball while the interval control sets the time, in seconds between each ball’s ejection. The speed dial can be set as high as 65 miles per hour, thereby imitating a hard drive shot at a speed few players would be able to replicate. The “oscillator” dial is a relatively new feature; when activated, The Ralph pivots side-to-side on the small disc under the machine. The oscillator can be set to deliver the balls alternately such that the first ball would go to one side of the court and the next one to the other in a predictable, continuous pattern. Or, it can be set at random so the player has to watch and be prepared to move to a delivery to either side of the court. Finally, there is a very small wireless remote that I can carry anywhere on both sides of the court’s net in order to stop the machine to rest, to fix a ball that is stuck, start/stop the oscillator feature, or to re-load the machine with balls. The battery lasts for about 4 hours of continuous use and there is an adapter that can be used to plug the machine into an electrical supply. To see the Tutor Plus in action and all its features explained, click here.

It might be apparent by now just how enamoured – addicted would not be too strong an adjective – I am of and with the game. It has hooked me escalating during the past 3 years into a kind of pandemic pickleball soliloquy of play. Below is a picture of me, masked at Greenhills’ indoor courts working on my serves:

Having a racket, in this case a paddle in my hand just feels like home to me; I know how to be and to move with a racket/paddle. About 15 inches long and 8 ounces in weight (though that can vary from 4-14 ounces). It is made from some combination of fibreglass, graphite, and/or carbon fibre often with some polymer surface embedding a honeycomb-structured core; the paddle is perhaps 3-4 cm in thickness. My current one is an Engage brand, Encore Pro:

There are all manner of recommended ways to grip the paddle and for me, it is no different than any other racket – turn the edge of the paddle face perpendicular to the ground, and then ‘shake hands’ with its grip, forefinger just slightly extended from the other fingers toward the paddle face. However the grip changes to a more western grip to impart over- or top-spin to the ball on the forehand. For the most part, the backhand grip is the shake-hands’ grip described above.

Strokes, grip pressure, and especially moving the body into position to hit the ball accurately are the essence of PB dexterity. Skill mastery, in whatever degree, has become a kind of obsessive quest for me, mindful as I am of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours of intensive practice to achieve mastery of complex skills (his Outliers‘ book) and football coach Vince Lombardi’s assertion that practice does not make perfect; rather, perfect practice makes perfect. The reality for me is that it’s not about achieving mastery or perfection, it is the process of striving to be better each time I practice and learn something new about playing.

Serving underhand has proven to be the wrinkle in my PB repertoire of developing competencies. Serving from the forehand side is a complex motion that starts with the feet about three feet apart and toes aligned in the diagonal direction toward the service court at which I aim. Using the western grip described previously, the ball is held below my hips, fingers cupped under – or over – the ball. The whole serving sequence begins by releasing my fingers to drop the ball (no toss) well out in front of my front leg while simultaneously initiating the paddle swing with the paddle held behind me and angled with the top edge of the face of the paddle slightly down toward the ground. That full- swing action is one of mostly shoulder-initiated movement, racket starting well behind my body elbow slightly bent. As I shift my body weight from back to front foot, keeping my core and diagonal body position stable, the racket comes down along the side of my body to contact the ball ideally at about 5 o’clock such that the top of the racket now faces the floor so that no part of the racket is above my wrist (or else it’s an illegal serve) and then, at contact, I continue to use light force to brush – that is the best word to describe how to hit almost any pickleball stroke…you brush the ball – the paddle over the ball to create top spin and follow through with my shoulders and hips rotating forcefully into the net and the paddle ending up in front and over my left shoulder, elbow bent at the culmination of the swing.

From the point of ball-contact, the action is a little like the same portion of a driver club golf swing at ball contact, just not as much follow through as a golfer might use. And a very key principle in both sports is to watch the ball right through follow-through rather than be in a hurry to see where the ball has gone. By accelerating arm and hip movement through the swing, I can alter the serve from slow pace, to moderate pace, and to fast-pace. My difficulty in learning to serve and all the “yips” I used to get making service errors stems from more than 5 decades of playing squash where almost all shots, including the serve were done with under-spin; in PB, most full strokes and most serves are hit with a top spin, brush-the-ball motion so that the ball clears the net easily and drops down into the court – under-spin tends to cause the ball to stay in the air longer and sail out too often.To get an idea of the complete serve, although he uses a bigger wind-up to his swing than I do, watch this video of world number 1 player, Ben Johns doing a power serve instructional video.

I provide all that detail here because it has only been in the last 6 months or so that I learned – meaning consistently performed – the proper mechanics of the forehand serve in lessons with Jay Francis, former squash pro at the London Squash Club where I was a member for decades. I took squash lessons from him and always got a lot out of his incredible ability to teach proper mechanics and to analyze my strokes and skills. Jay has become just as adept in his PB coaching, achieving pro status very quickly since taking up the game in the past few years. I want to ingrain and imprint what he has taught me about serving and one of the best ways for me to do that is to describe what I learned and I did that above.

The whole service technique is very different from any racket sport I’ve played. In badminton, the high serve is a very big underhand arc, pendulum-like with a lot of wrist and follow through toward the ceiling. In squash, the serve is done using a backhand stroke that is side-arm, mostly, because there is no wrist-below-the-racket rule and there is a step motion toward the court into which one is serving. I suspect my body has to un-learn my service habits from those two sports. Some PB players use an almost completely underhanded push type of pendulum-motion serve that eliminates a lot of potential mechanical errors; however, that style results in a very predictable, one-dimensional serve. In the service style I am trying to master, I can vary power, direction, depth, and even alter the swing with a subtle change of wrist motion to create side-spin. Rarely is a serve so effective that you ace opponents. What I seek is to be unpredictable about where the ball is going in my opponent’s court, what spin I use, and how hard I hit the ball, all in effort to elicit a return that is weak, short, poor, or even an error (ball out of the court and/or into the net) from opponents.

Returning a PB serve is quite prescribed. Because the service court extends to the PB court baseline, returning requires one to stand behind the baseline – for servers who are able to hit hard, a good 5-6 feet behind the baseline; you have to let the ball bounce before hitting it (just as you do in tennis). The serving team has to stay at their baseline after delivering their serve because another PB rule is that you cannot hit the ball out of the air, that is, volley it until the return of service shot has bounced and the serving team has, in turn, hit that service-return. Hitting a service-return shot is called the 3rd shot in pickleball. Once the third shot is hit, any shot can be made as long as you don’t step in the kitchen when hitting the ball out of the air or don’t let the ball bounce twice. Service returns are kind of my forte in that the strokes, forehand, and backhand are more like squash strokes although top-spin still reigns supreme for ball control.

The fundamental part of any PB stroke is footwork, getting to the ball and getting set to hit it without being caught still moving toward or away from the ball. As any ball is being hit, players need to be in a ready or what’s called an “athletic stance,” racket up in front of the chest – though there is an exception described below – with slightly bent elbows. torso facing the net, feet about shoulder width apart, knees bent, weight evenly distributed and mostly toward the balls of the feet. A lot of players even bounce on their feet ever so slightly as their opponent is about to hit the ball or do one bounce just before they move after the ball is struck by the opposing player. The whole idea is to be ready to move in any direction depending on where the ball is hit. The athletic position I learned a long time ago in badminton and from many years of “getting to the T” and in the ready position in squash. And yet, like everyone, I often get caught still moving, being late to get into the ready position, or, I kind of plant myself, rooted to one spot as though I were going to brace myself for full body contact more akin to what a wrestler might do.

Service and service returns are the bread-and-butter of the game, absolutely necessary skills. For me, PB becomes exponentially more interesting from the 3rd shot on into rallies, the latter can be 5, 10, 20 or more reciprocated shots dependent on players’ prowess. Even more intriguing to me is the fact that the game, especially its doubles format (I rarely play singles and if I do, I play a variation of it called skinny or half-court singles), requires so much court awareness, preparedness, and focus of thought. I read somewhere that creativity is intelligence at play and I find that so apt for PB games; in my view, pickleball requires focused awareness and making stroke decisions based on multiple factors – it is then, an intelligent game made more intriguing by players’ creativity.

Ball-tracking is an understated prerequisite; the ball looks like this:

Very much like scoop-ball balls, they are plastic, with 26 holes for indoor balls and 40 holes with thicker plastic for outdoor balls – yup, I counted the holes. The greater number of holes and thicker plastic is a design to try to lessen wind effects outdoors. There are all manner of different ball brands and they are easy to purchase in any quantity one desires. Unique to this court game is the sound made when the paddle strikes the ball; it’s a distinct percussive POP and the sound carries. In fact, noise complaints, even law suits in the US – see this current article – are becoming prevalent especially for outdoor courts in community areas that are close to residences. In hot, Summer weather, picklers prefer early morning, 7 or even 6 AM cooler temperatures and I sympathize with folks who live near outdoor courts and I will not play or drill before 8 in the morning.

The pickle ball is slippery to the touch, compared to say a tennis ball. That said, skilled players are able to apply all kinds of spin, side-, under-, top-spins all in efforts to make opponents make an error or hit a weak return. After the service return mentioned above, most players hit either a 3rd shot drop or 3rd shot drive. The former is a very specialized shot that takes a lot of practice. The idea is to contact the ball at its apex and with subtle but distinct weight transfer, hit a ‘touch’ shot that clears the net and lands within the kitchen such that opponents can’t volley it and are forced to hit a relatively neutral return. Thereafter, players get into what is termed a ‘dink’ or short drop-shot game where both teams stand just behind their respective non volley zone lines and hit touch or lighter shots in efforts to force errors by moving opponents side-to-side, up-and-back and even, on occasion, hitting lob shots over your opponents’ reach to land in the back of the court. Dink shots are just very controlled drop shots executed with lots of top- (commonly) or under-spin, clearing the net by 4-6 inches and landing lightly in the kitchen; that lightness of touch is made even finer by bending one’s knees in even more of a crouch position and then gently coming up, engaging your core, as you brush the ball with the paddle. If possible, players try to volley the ball rather than let it bounce. When it does bounce, the most effective drop shot is made when the ball reaches its rebound apex after the bounce; hitting it too soon or too close to the bounce-spot often pops the ball up too high over the net enabling the opposing players to smash it.

The dink or short drop shot game, played well is like watching a dance among 4 players. Each pair has to be aware of their partner’s court position; for example, if my partner on the forehand side of the court is drawn toward their sideline to retrieve a dink shot, I have to move just over the centre line, back about a foot from the kitchen boundary line, body turned slightly toward my partner to prevent an easy return shot made down the centre of the court (down the middle solves the riddle, as one of my PB friends often opines just because so many points are won on that shot). At the same time, while positioned to cover the middle, I have to be balanced in the ready position and able to move sideways back to my side of the court to cover dink returns after my partner has hit their shot. So, even when you are not actually returning the ball on your team, you kind of ghost-hit or get into position in concert with your playing partner as well as being aware of the court position of your opponents.

Many of my coaches call this dink-shot-dance a respect the X concept where the imaginary X-points connect the two players and the X-space between them expands and contracts with players’ conjoined positioning movements. For example, if my partner has to move laterally toward the side boundary of their side of the court, I have to move with them to cover the centre of the court against the potential of our opponents returning the dink shot to the opened up centre of the court. Dink shots are made from the shoulder, not the wrist and that took me some time to realize. Even more, your grip strength is less for playing the dink game. As I learned from Jay, if I hold the paddle as tight as I can with a cocked wrist, that would be a 10 grip; if let the paddle kind of dangle in my finger-tips, that would be a 0 or a 1 grip. Dinking is done with about a 5, or lighter, more relaxed grip in order to ‘feel’ the stroke more acutely and to keep dink balls relatively low to the net. A key component of dinking – and probably any stroke in PB – is remembering to breathe; it’s so easy to get tense, hunch one’s shoulders and thereby detract from making fluid, effective strokes.

The dance analogy in the dink game extends to players’ movements side-to-side. For the most part, to get to dink shots hit to the outside of the court, you side-step or shuffle sideways, kind of sideways, crab-like from the athletic position. Any cross-over step is done as the last reach for the ball, almost always on the backhand side, rarely on the forehand; as you do that cross-over step, the back foot pivots up either to one’s toes or onto the side of that foot in order to slightly turn one’s hips and maximize the player’s reach. That said, cross-over steps limit recovery time to get back into position for your opponents’ return shot – better in most cases, to pivot at the hips, get behind the ball with the paddle, and raise the trail foot without any cross-over step. For those readers now captivated by this blog – ahem – you can see a really good analysis of pros playing the dink game here. One other unique aspect of dinking is the art of hitting a backhand dink shot; it is done with the wrist cocked as though the top of the hand holding the paddle is perpendicular to the floor and the fingers farther forward than the wrist. The paddle is flat and the whole motion is from the shoulder and arm, no or very little wrist action. Doing it effectively in this manner is predicated on getting your body into position behind the ball, hips turned, trail leg’s foot on its side or up on the toes. Mastering this backhand-cocked-wrist-stroke for dinking means the player has optimal control of where to return the ball, by choice, rather than merely reacting to the ball in a hurried manner.

The whole dink game is predicated on a good, accurate third shot. Most third shots are hit diagonally to give the hitter time to move forward to get as close as possible to the kitchen line before the 3rd shot is returned. The more each team can stay at the kitchen and continue the dink game, the more that team is in control of the game offensively and they are not being forced to retreat or hit backward in the court or be forced into defensive shots like turning to run toward their baseline to retrieve a lob shot. This dink shot game, the dance-like movements, and the necessity for players to stay out of the kitchen unless the ball bounces first in that zone is what makes pickleball unique from other court sports where one can be right at the net or right at the front wall (tennis, badminton, squash, racquetball). Creative, well-timed, well-placed shots, and above all, lots of patience (waiting for the right time to try to make a winner rather than forcing or attempting a winning shot too soon) are the essence of good dink play. In the last few years, clubs have hosted ‘dinking-only’ tournamets, just for the sheer fun of doing so and for adding a competitive, skill element to dinking. At Greenhills, Sharon Scarfone (my very first pickleball coach) has orchestrated all manner of clinics, group events, social events. For example, in May 2023, she organized this dinking game event, Dinko de Mayo:

Notice how much Sharon emphasizes the fun aspect of the game. I think that three letter word – f-u-n – pretty much captures my raptures with the game in all its aspects. One writer calls pickleball the Goldilocks of racket sports – it just feels right.

The other third shot is the drive, executed with either forehand or backhand top-spin, usually, strokes wherein the paddle makes as much brushing-stroke contact with as much of the ball as possible, that is, bending low at the knees and contacting the ball at 5 o’clock (forehand) or 7 o’clock (backhand) and brushing up over the roundness of the ball facing your paddle. Top-spin, if hit correctly, results in being able to see your knuckles at the top and follow-through of the forehand and your finger nails at the top and follow-through of your backhand. Hitting the ball hard – driving it – right at your opponents, down the sidelines, or toward the centre of the court (the latter to induce hesitancy and perhaps an error from the your opponents trying to decide who should take the centre-shot drive), is a good tactic on the 3rd shot in that if done well – almost always with top-spin – it engenders a defensive and relatively harmless block-return from opponents. From that blocked shot return, your (now) 5th shot offers all manner of options depending on the quality and placement of the blocked return. Most often, among teams of equal strengths, the 5th shot is a drop into the kitchen, often toward either outside corner, and the dink game re-develops.

In terms of spatial movement, pickleball games proceed both laterally and from back-to-front (at times, front-to-back) in the court. Most of the up-and-back movement follows two situations. One, the person hitting the return of serve normally tries to return deep into the opponents’ court to give the returner time to move quickly toward the kitchen boundary or 7-foot line (their partner is already stationed at that line on their half of the court). Two, the serving team stays behind the baseline until one of them is about to hit the 3rd shot (from their opponents’ return of serve). Team movement on the 3rd shot is quite important; let’s call the team Player A and Player B. If player A is preparing to make the third shot (partner communication is important to make sure one player is going to take the shot especially if the return has come down the centre of the court; most teams arrange to say, “mine” or “you”), then player B creeps forward a few steps. If player A hits a good drop shot, then B moves quickly to the kitchen line. However, if player A hits the return too high or drives it, then B stays put in a modified paddle-ready position – see below – in an area of the court informally called the transition zone (TZ). The TZ is about 6-7 feet inside the baseline and it is the one area of the court where the TZ-positioned player holds their paddle lower, about knee height, rather than in front of their chest as they would at the kitchen or baseline. Most shots coming into the TZ will be low shots either soft ones the opposing team directs at the feet of the TZ player/s or the shot is hit down hard by the opposing team. In either case, having the paddle already lower toward the ground and more in between the feet creates a preparedness to make an effective return. Depending on the TZ player’s handling of any shot coming toward them, their team-mate either stays at the kitchen line (if the TZ player’s shot is a good one) or moves back to be in parallel with their partner to defend against mid-court shots.

As mentioned above, PB is a game of creativity – there is a mind-scape as well as a landscape to the game – and in terms of shot-making and creative decision-making (instantaneous or instinctual or conscious) about shots, it is also a game of geometry – of using and generating angles. In fact, one avid player, Daryl DeFord happens to be a math professor at Washington State University and he has created an online mini-book called Pickleball Diagrams in which he examines and illustrates, with cartoon court vector diagrams, different concepts and possibilities about shot angles. Part of the tactics (actual manoeuvres) and strategy/ies (overall game plans) involves using angles to create point-winning opportunities – hitting at the body of your opponent or hitting cross-court to maximize the distance and pace you can apply to a shot or hitting a cross-court dink very close to the net into the kitchen. Most PB shots are hit forehand or backhand and in addition to using angles for shot effectiveness, players apply spin to the ball. For example, at the 7-foot line, you can volley a ball even if it is below the top of the net when it gets to your paddle, if it’s within your reach; hitting that volley is often done by applying brush-like topspin to the ball as though ‘brushing’ over the ball from near the base or handle of the paddle down toward its tip. Applying that spin means that you keep the ball low and directed toward your opponents’ feet forcing them to make a neutral return rather than being able to attack a ball that is popped up above the net.

And there are specialized shots created from using angles. For example, in the dink game, often players will hit a really good angle shot such that the ball bounces very close to the sideline of the kitchen. Its trajectory might be such that after the bounce, the ball is actually sitting up and still moving well outside the court’s lateral boundary line. Adept players, by getting their body into position quickly behind the ball, can actually direct the ball low and hard around the net post and into their opponents’ court. That shot is called an ATP, Around-The-Post shot and is fairly common especially at the pro and more skilled playing levels. Another specialized shot is called an erne (er-knee). During the dink game, forcing your opponent to move back from the 7-foot line and toward their sideline often means their return will be straight back over the net toward the same sideline and often the returned ball might be a little higher over the net than usual and/or they might be slow in recovering to their kitchen line. In anticipation of that kind of higher-than-normal sideline return or late recovery, adept players jump over their kitchen corner area at the seven foot line and while still in the air, hits the ball hard, downward just after it comes over the net and then the player lands outside of the width court boundary so as not to step on any part of the kitchen – that is an erne shot in PB and for those interested, you can see it done at this link. In the same vein, players will often anticipate short, weak returns into the middle of the court and will “poach” or move quickly across the 7-foot line to cut off the return and volley it down hard at their opponents’ feet. Poaching is kind of a stealth-like move in that you don’t want your opponents to see you doing it until after they have committed to hitting the ball; done too quickly and the player poaching leaves too much empty court space available for an easy put-away shot from their opponents.

All human movement occurs in a series of complex (often) arcs. The action of hitting a PB ball involves all of the intersecting arcs of moving one’s body into position and then the actual arm/body action of hitting the ball. Timing then, in any movement endeavour comes down to the physics of movement, that is, getting the arcs to intersect at the most efficient spot in the movement sequence – the whole concept of timing boils down to this arc intersection at just the right time and place in the movement sequence. In pickleball, players need to be in the ready or athletic position, move to the ball, hit the ball, and then recover to the athletic and good court position to be ready for their opponents’ return. If you watch a PB game video, it all looks so efficient and effortless even with accelerated ball trajectories; advanced skills contribute, clearly, to that ease or flow of movement. There is an expression attributed to Navy Seal training that says, ‘smooth is slow and slow is fast.’ It means that often the quickest way to get any task done efficiently is to be deliberate, methodical, and apparently slow. This doesn’t mean all movement and shots in PB are slow; often, there are “firefights” (example video here) at the opposing 7-foot lines with the ball volleyed back and forth very hard, almost parallel to the floor until one team makes an error or is able to neutralize the power by blocking their return into the kitchen thereby (re)initiating the dink game. The seemingly slow aspect of learning the game also applies to letting a ball reach its apex before trying to hit it. The higher the ball is in its flight, the less chance there is of making an error. Too often, players try to hit the ball right after it bounces; doing so takes precise timing and a deftly-correct paddle angle because you are almost predicated to hit the ball too high or into the net from taking it too early.

Very likely, there was a tipping point (Gladwell again, his 2000 book, The Tipping Point) – the “critical juncture at which unstoppable change takes place” – for me that self-propelled me into my PB immersion, an obsession if I’m being honest. I don’t think it was any one element that tipped me, more a nexus of new skill allure (particularly the brushing-like stroke skill); the familiarity of court/racket/ball; the challenge of change in strategy related to the kitchen; and then the sheer jollification of playing the game. There is so much more I could explore and describe about this magical game; for example, stacking, a pickleball strategy that is used to keep each partner on a doubles pickleball team on their preferred side of the court – a more detailed explanation can be seen here. I suppose that overall, it is the game itself, playing the game that is so magnetic to me. And by game, I mean it in the sense of one of the finest explorations of what a sporting ‘game’ means and that is Ken Dryden’s, ostensibly hockey treatise, The Game (see my own analysis of that book here). Playing pickleball is to engage in a game that moves, breathes, contains, and envelops players, is never the same (like the proverbial you can never step in the same river twice, so too is each PB game its own ‘river’), and is always a pattern, a kaleidoscope of movement sequences, a dance with paddles, partners, and opponents. There is a numerical ranking system in PB, one that categorizes players from beginner (Level 1) to expert (Level 5); professionals are at least level 5 and something beyond that level. The levels are there to establish equality of competition in tournaments and they give players something for which to strive in their commitment to being better players. Unlike a lot of racket sports, almost anyone can enjoy pickleball from the first time they hit the ball with a paddle. It is often said about PB that it is easy to learn, difficult to master.

In its growth and dispersion, there is just so much by way of information, help, resources, tips, videos (youtube is replete with PB videos), podcasts like this ‘4.0 to Pro‘ one on Spotify, equipment brands – the trappings of the game – that are widely available. One can go right to hand-eye coordination basics as in this video drill or, as I have, find one really good PB book like Dunmeyer’s Pickleball 5.0: A Journey From 2.0 to 5.0:

Even The Ralph has evolved into the pickleball spin ultra Pickleball Tutor ball machine; using the “presets” and “drills,” you can ‘teach’ the machine to teach you by exact shot feeds:

I can create the same shots on The Ralph – dinks, lobs, third shot drops – I just can’t do it with pre-set functions; I have to set up the feed manually by adjusting the elevation and speed. Without question, pickleball is exploding in player popularity, in its professionalization and commercialization, in court and facility construction and so forth. Locally, I have been part of a planning team looking to create a Southwestern Ontario Pickleball & Squash Centre (SWOPS). About 8 or 10 of us met regularly over Zoom for about 8-10 months to conceptualize a multi-court pickleball, squash, and Padel (pronounce Pah-dell) sport facility. One of my tasks was to work with a logo designer to come up with a distinctive logo and we did that with this one:

The font on the logo letters is deliberately and subtly slanted to create a sense of motion; the ball is a hybrid of a squash and a pickle ball, true even to the colour of each ball, respectively. The stylized racket and paddle face-centred over the ball are meant to characterize or symbolize the sports promoted in the SWOPS Centre. Of fascination to me in working with the logo designer was knowing that they resided in a non North American company and had never seen either squash or pickleball being played. My role in the logo creation was to explain what we wanted represented in the logo and then keep re-drafting and re-shaping as the designer came up with different variations. After months of meetings, creating an online presence with a SWOPS website, we created a template a “vision [to] to build a centre that encourages all ages and skill levels to live a healthy lifestyle by playing pickleball and squash.” In essence, we envisioned a modern, professionally managed, affordable, and not-for-profit centre ecapsulating the three court sports and the marriage of 3 core values: fun, fitness, and friendship. Its features were to include a kitchen, dining area, licensed lounge, competitive quality courts with sliding glass sidewalls in order to use the floor space for other gym functions. And we added in Padel, a rapidly growing court game that is kind of a combination of squash and pickleball played in enclosed court. Right now, this vibrant concept sits quiescent, awaiting developer interests. Key to the Centre’s creation is funding. The champion – the engine and the energizer – behind this concept is Murray Shaw, a very skilled squash and picklebll player and very successful business person with a lot of entrepreneurial experience and expertise. With any luck and lots more work, some day the SWOPS Centre – or something like it – will come to fruition.

There are so many other aspects of playing pickleball that I could have described, believe it or not. Stacking, for example, comes to mind; stacking is a PB strategy that is used to keep each partner on a doubles team on their preferred side of the court and it takes time and excellent communication skills to learn – a more detailed explanation can be seen here. As of today, the best single online PB resource of which I am aware is a blog by ‘Pickler‘ – that blogger includes recent topical or thematic blogs as well as categorized links to just about every aspect of the game from rules, equipment, videos, and pickleball camps. In terms of my pickleball passion, the reality, for me it is the feel of the game; the balance of the paddle in my hand; the sound and reverberation of a shot well-hit; the joy of effort; and the “dance” of movements that I and my fellow players create every time we step onto a court and engage in PB play. I am reminded of W.B Yeats’ eternal question, how can we tell the dancer from the dance – how can we tell a PB player from the PB game – when there are so many creative ways to play this marvelous game, so many dancers, so many games, so many moments of sheer rapture that are possible. As with all sports – and probably many other activities in life – I believe the teachings, meanings, and implications of playing PB are not just contained within the physicality of the activity per se. I believe we, as players are offered multiple opportunities to learn communication, team-work, patience, cooperation, respect, fairness, equity, kindness…and so many other human qualities that reside within and around the ‘court’ of pickleball’s domain. Whether in my Covid solitude of play – me and my Shadow and/or me and The Ralph – or with other players, with gratitude, I tumble home to my new 44 X 20 court sport, pickleball and revel – become pickled pink from the neuro-physiology of enchantment – in all its splendour, gameness, and life lessons for this humble pickler.

Back on my outdoor courts: 11 April 2023, the Kilworth courts were just re-opened after being locked all Winter, nets installed, clear blue sky, 25 degrees, some wind…fabulous day in which to work on serves and drive shots from The Ralph:

Addendum 26 June 2023: I added another implement to my PB court equipment repertoire; it is a cart for carrying all my stuff: 130 PB balls; The Ralph; The Huston; my pack; and my newest serving PB caddy on the front of the cart (its arms swing down to put the caddy part at the top and it has wheels and it can pick up balls from the court by an easy push-down action):

I call this new device, my cart, very simply and elegantly à la – it might take a moment to realize the aptness of the name. Finally, in Jen’s 2023 vegetable garden, we utilized old pickleballs as an eye-safety device on top of the tomato stakes…

Kind of like old farmhouse/barn lightning rods, they add colour beyond their utilitarian function. And as the popularity of pickleball continues to skyrocket, whimsical cartoons abound, like this one from The New Yorker 5 June 2023:

And as Fall closes fast toward Winter 2023/24, my thoughts and imagination turn toward fanciful pickleball:

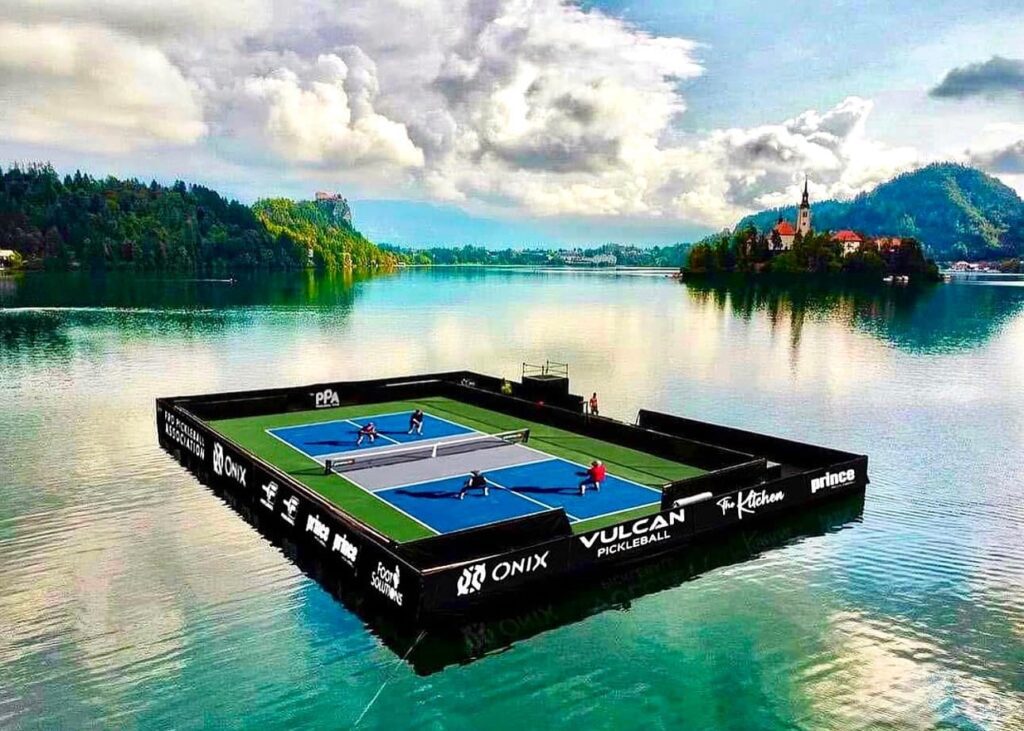

Not sure where this is but it’s not far off the mark for PB addicts like me…boots to crampons to skates, soon another Olympic sport! And then there is the floating court…

Or, on cruise ships: