Wrestling John Irving

Reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic (the three ‘Rs’) have been my companions throughout most of my life. Arithmetic or math fascinated me as a subject for most of my elementary and high school years. Above the blackboards in my classrroms were both alphabet cards – with letters in print and writing – and number cards in dots, 1 dot for the number 1; two dots side-by-side for 2; 3 dots in triangle shape for 3 etc; I actually did addition picturing and finger-imitating those dots…still do, sometimes.The dot-number-representations looked like the top two rows in this workbook:

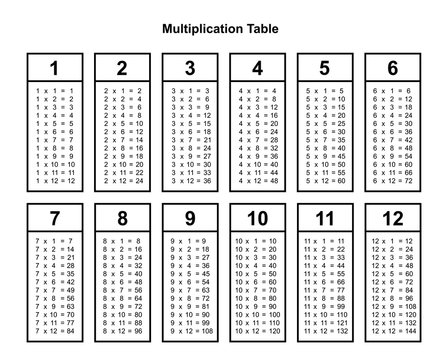

Proudly, I mastered the arithmetic “times’ tables” from sheer memory work – what’s 8 times 12? and the answer was immediate – and even loved that the back cover (always brown, in my memory) of most of my public school, page-lined workbooks featured the multiplication tables, like this:

I suspect memorizing/learning these has disappeared from contemporary curricula in deference to portable calculators, cell phone apps etc. Thanks to my father’s shared skill with numbers, I could ‘do’ math – addition, subtraction, division, multiplication – readily and easily in my head. Geometry ‘problems’ were challenges I could not resist. My math, as a school subject, passion was squelched in grade 11 by one math teacher, Mr Letts, Eddie Letts, bald, dour, and imposing – my venom has a memory – to me. Throughout my secondary school years, I worked in tobacco harvests on farms near Simcoe – see my Hanging Kiln blog – and those harvests lasted well into the third week of September. I felt committed to the farmers with whom I worked to finish the harvest and the wages were superb. Thus, I came back to school 2-3 weeks ‘late.’ In the Fall of 1964, my grade 11 year, math changed from being arithmetic, trigonometry, geometry etc.; in its stead was what I came to know as “the new math.” When I arrived in Mr Letts’ class, the new math he taught was literally a foreign concept to me; I had no idea what was going on, could not fathom what he was teaching. As was my wont, when I asked him for help, he derided me for coming back to school late and expecting ‘everyone,’ especially teachers, in his view, to help me and how very inconsiderate that expectation of entitlement was. He said it was my job, not his, to get caught up. In class, he’d deliberately ask me questions during lessons knowing full well that I had no ability to answer them/him; he belittled me in front of my peers and I felt shame. I failed the first tests miserably, never having failed anything in school in my life. With my friends’ guidance and assistance, I managed to pass grade 11 math, just barely. However, I gave up that kind of ‘rithmetic as a subject and turned my academic attention to the humanities, languages (French, German, and Latin) and especially to English literature – ‘reading and ‘riting.

With respect to reading, among many authors that have inspired me in their novel-writing, John Irving’s novels seemed to magnetize me for most of the mid 1970s to late 1990s. To date, his 15 novels are:

Setting Free the Bears 1968

The Water-Method Man 1972

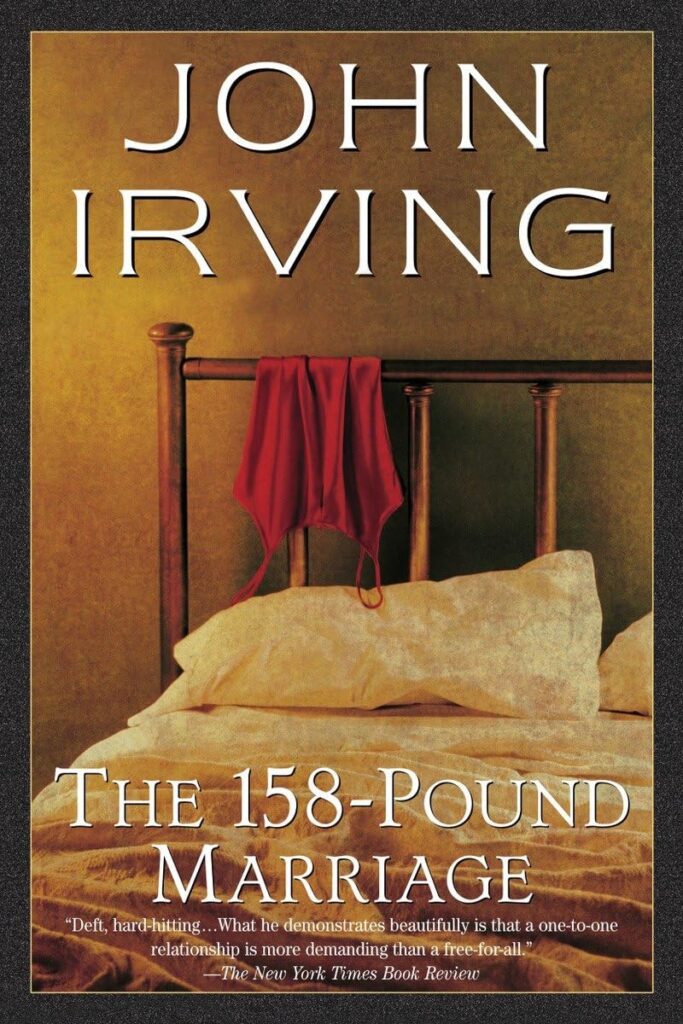

The 158-Pound Marriage 1974

The World According to Garp 1978

The Hotel New Hampshire 1981

The Cider House Rules 1985

A Prayer for Owen Meany 1989

A Son of the Circus 1994

A Widow for One Year 1998

The Fourth Hand 2001

Until I Find You 2005

Last Night in Twisted River 2009

In One Person 2012

Avenue of Mysteries 2015

The Last Chairlift 2022

I read every one from Setting Free the Bears through to The Fourth Hand and then kind of lost interest. The publication of John Irving’s The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir (1996) confirmed a long-standing perception that a wrestling motif underpins, wrestling pun intended, most, if not all of John Irving’s novels. ‘Restling – a 4th ‘R’ – never interested me as much as my lifelong captivation with ‘r’acket – a 5th ‘R’ – sports – see my courts…fives to pickleball blog. In high school, we did a couple of units of wrestling in PE class, just as we did in an activity in Undergraduate Kinesiology. Yet it seemed more a skill set or a sport for others, just not for me. Irving’s literary cast on wrestling brought a kind of intellectual interest in the sport.

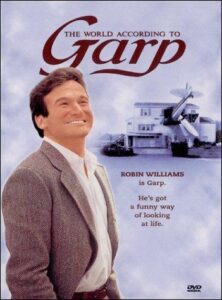

Of his eight novels published between 1968 and 1994, all make at least some mention of wrestling; several of them rely on wrestling as a dominant part of the story and as a significant and pervasive metaphor. For example, in The World According to Garp (hereafter, Garp), by far his most popular novel with millions of copies sold, wrestling activity, wrestling terminology, wrestling rooms infuse and inform Garp’s character. In passing, the 1982-released movie version starring the inimitable Robin Williams was a superb version of The World According to Garp and its dark exploration of gender and sexuality:

Back to Irving’s books. What provokes the discerning imagination is the very fact that wrestling could be made to work in good literature. After all, in wrestling, we have the most elemental of physical contests, the most classic (and Classical) of ancient Greek sports, this strigil-scraping, palaestra-centred [palaestrae were literally Greek wrestling schools, the ruins of which abound still], body-oiling, sand-rolling, and so basically sweaty sport – undertaken by men and boys in the nude – from 4th and 5th century B.C. (or earlier) Greece and from the oldest literature known to western civilization (Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey) and even from eastern cultures pre-dating those epic works. These palaestrae were just large, outdoor squares surrounded on all 4 sides by columns supporting roofed areas, like this preserved palaestra in contemporary Pompeii – the surface would have been sand, not grass and likely devoid of trees in the interior:

A strigil – mentioned above – was curved, metal body-scraper used by the wrestlers to smooth the oil and sand with which they anointed themselves all over; it looked like this:

There are some marvellous pieces of statuary that depict wrestling in ancient Greece, like this one that now rests in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy:

In the Old Testament or Hebrew book of Genesis (32: 22-32), the patriarch Jacob wrestles all night with an angel, presumed to be representative of God. All manner of art exists that images this contest, one that often is associated with the founding of the Jewish nation:

And yet today, wrestling, true wrestling is only popular in western culture in selected countries or in pockets of interest areas. In North America, so-called “professional” wrestling, choreographed, faked, hyped, and staged, has supplanted public interest in and knowledge about true wrestling.

Therefore, it seems logical to conclude that it would take considerable skill on Irving’s part to make wrestling work for a relatively naïve, North American audience. Wrestling is used so subtly in D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love when Gerald and Rupert wrestle naked – significant in Lawrence’s literal depiction of homoeroticism – in the drawing room reflected in, arguably, the novel’s most famous passage:

So the two men entwined and wrestled with each other, working nearer and nearer. Both were white and clear, but Gerald flushed smart red where he was touched, and Birkin remained white and tense. He seemed to penetrate into Gerald’s more solid, more diffuse bulk, to interfuse his body through the body of the other, as if to bring it subtly into subjection, always seizing with some rapid necromantic fore-knowledge every motion of the other flesh, converting and counteracting it, playing upon the limbs and trunk of Gerald like some hard wind. It was as if Birkin’s whole physical intelligence interpenetrated into Gerald’s body, as if his fine, sublimated energy entered into the flesh of the fuller man, like some potency, casting a fine net, a prison, through the muscles into the very depths of Gerald’s physical being.

Though written half a century before Irving’s writings, Lawrence’s wrestling depiction lacks, in my view, the richness of wrestling terminology and nuances that Irving uses so adeptly. Pointedly, the sport looms within and is central to Irving’s novels. In a 1979 issue of Rolling Stone magazine, the author himself stated:

Surely much more important to my life than it ever was to Garp’s was the wrestling….My wrestling coach really got me through the place. Wrestling became more and more important – metaphorically too. I was not a very good wrestler, but I did well: that is, I beat a lot of people who were better than I was.

Indeed, Irving makes a declaration near the very end of what is less a “memoir” than a book about the significance of wrestling in his personal life, The Imaginary Girlfriend:

I want you [the reader] to understand that the distance between my writing and my wrestling is never great. (p. 138, brackets mine)

In fact, after a relatively unheralded high school wrestling career, Irving attended several American universities (and one European university) whereat he felt he “learned more from wrestling than from Creative Writing classes” (p. 128). He opines:

…good writing means rewriting and good wrestling is a matter of redoing – repetition without cease is obligatory, until the moves become second nature….What I am is a good rewriter; I never got anything right the first time – I just know how to revise and revise. (P. 128)

And even more focused toward the intersection of wrestling and writing:

My life in wrestling was one-eighth talent and seven-eighths discipline. I believe that my life as a writer consists of one-eighth talent and seven-eighths discipline too. (p. 126)

These inferences about the parallels between WR-estl/it-ING were not apparent to Irving as a university student when he felt the two mixed about as well as the proverbial oil and water. Yet his passion for the sport resulted in a coaching career that lasted until he was 47 and in his election to the National Wrestling Hall of Fame, albeit by the “back door,” as he confesses in The Imaginary Girlfriend (p. 136). One of Irving’s sons, Brendan won the New England Class ‘A’ wrestling title, an achievement about which John Irving gushes, “It was the happiest night of my life” (The Imaginary Girlfriend, p. 115).

Irving is equally sentimental in his writing and he feels it is a novelist’s primary responsibility to tell a story well. In that regard, he was heavily influenced by Dickens’ “feast of language” and story-telling skills along with those of Kurt Vonnegut with whom he studied for their Master of Fine Arts’ degrees at the University of Iowa. Primarily, Irving’s art of writing is engagement; he engages his reader just as one engages, literally, an opponent in wrestling. To “wrestle” John Irving is to grapple with his balance of building imaginative constructs on top of a groundwork use of autobiography and history. Irving takes real stories, real incidents and makes them better with his fictional adroitness. The key to engaging Irving, in turn, is to realize that the characters are enmeshed in themselves and the reader is drawn into them and their stories.

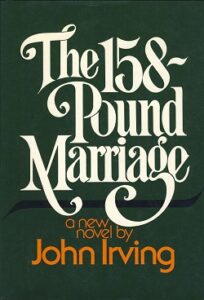

One critic has written that Irving’s universe is largely governed by mishap, violence, and the irrational and his readers have to learn to deal with the chaos of those elements combined (for example, the penis bite or the Under Toad in Garp or “Sorrow Floats” – itself one of the most brilliant metaphors – albeit slightly overused – comparing thematically a taxidermied, family dog, Sorrow who literally floats to the resilient human emotion of sorrow – in all of Irving’s writings – in The Hotel New Hampshire). The lure to Irving is to witness how his characters combat – shamelessly, I underline wrestling terms that become double entendres in this blog – the chaos by the assertion of self – they learn to grapple with mishap, violence, evil, and the irrational. Fathoming John Irving is not like peeling back layers of onion skin to reveal meaning and significance; rather, it’s more like unravelling some kind of literary DNA only to discover circles within circles or double helixes of meaning. The “baroque” aspect of his novels is overwhelming in that they truly are fantastically over-decorated, gaudily ornate in detail with curved lines of plot and character development. My intent here is to examine how that richness is derived from the wrestling motif in what critics suggest is his “darkest” novel – a perception I don’t share – The 158-Pound Marriage (1974 – a first edition featuring the cover below, currently retails for $350 US on e-bay):

First, it is important to look at the structural elements in this novel. The title itself alludes to a middleweight weight class and to the central issue in the novel, the morality of mate-swapping intra-and extra-maritally. Chapter titles are important to the wrestling backdrop:

- The Angel Called “The Smile of Reims”

- Scouting Reports: Edith [126-pound Class]

- Scouting Reports: Utch [134-pound Class]

- Scouting Reports: Severin [158-pound Class]

- Preliminary Positions

- Who’s on Top? Where’s the Bottom?

- Carnival’s Quarrel with Lent

- The Wrestling-Room Lover

- The Runner-Up Syndrome

- Back to Vienna

Sandwiched thickly between the first and last chapter titles are eight chapters with direct or indirect implications from wrestling to sexuality to marriage, even chapter 7, although it is not readily apparent from the title. Three of the four main characters form the subjects of three of the early chapters, Edith, Utch, and Severin, the latter a college wrestling coach. The fourth character, the Narrator is one whose name we never learn and who tells the whole story from his (presumably male) singular and biased perspective. The “158-Pound” component of the book’s title refers to Severin’s weight class when he was a university-level wrestler as well as to his star athlete, George James Bender (note the name, a double entendre for wrestling and sexuality, as this paper reveals). Bender is an odds-on favourite for a national wrestling title. How “Marriage”, in the title, is in a 158-pound weight class is the central question of the novel and, in certain respects, this blog.

The structural perspective of the novel is quite simple: the Narrator is the sole voice of the book. All viewpoints come through him; we are left to filter any truth and meaning. The Narrator is husband to Utch(ka), father to their two sons, and an academic who is a writer of historical novels. His position on sport is made explicitly clear early in the novel: “Everyone says the academic life is one long prayer to detail, but it’s hard to match athletics for a life of endless, boring statistics” (p.27). Both frustrating and alluring is the fact that the Narrator’s perspective is the lens of the whole novel: it’s as though he drops in on some particular situation for one or all of the characters and unravels a bit of their personal/social-DNA, as he perceives it/them, and then moves on to some other strand of social behaviour or character study. All we know about him physically is: “I am tall and thin; even my beard is narrow” and “I was never an athlete” (page 87). His favourite word, he says, is ‘yield’ (p. 189) something antithetical, for the most part, to wrestling or even to asserting something of himself. For John Irving, having this Narrator-character who is so oblivious to the world of sport is a clever strategy. The Narrator becomes Irving’s devil’s advocate in that he is the opposite of Irving’s personal perspective on living, on growing and, in this case, on wrestling. To make the novel work, the reader almost has to dismiss the Narrator’s self-centred and biased viewpoints. And it does work. Neither critics of the novel or its readers admire the Narrator – he has no redeeming qualities and he learns nothing from the experimental foursome and its aftermath.

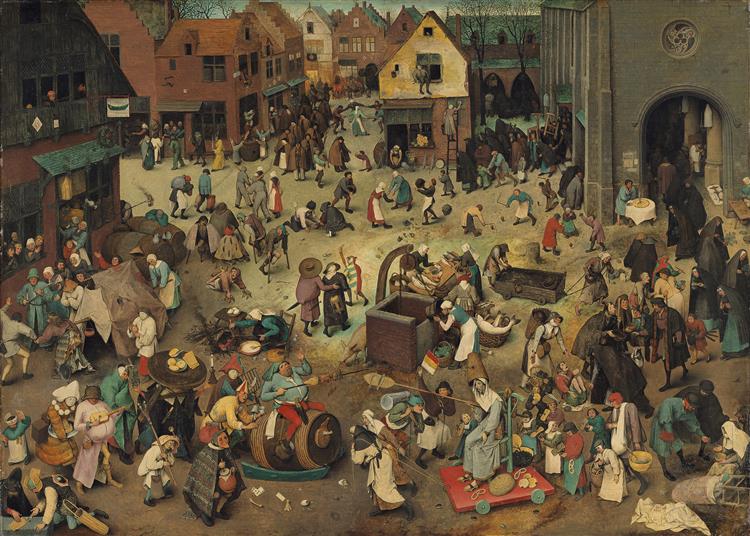

For the purpose of this analysis, the Narrator is critical to the significance of the book with respect to wrestling as a backdrop and metaphor. For one reason, Irving has to work hard to convince us how obtuse the Narrator is without going overboard. More fundamental to the structure of the novel – and this is something I found critics/analysts have missed about this piece of literature – the Narrator fantasizes constantly about writing a novel to be called The Quarrel Between Carnival and Lent. This explains the title of chapter seven; however, it also forces us to look at the thematic repercussions of the Narrator’s fantasy-allusion to Pieter Bruegel’s 1559 painting, “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent”:

Irving’s use of this painting is extremely clever and very apropos of the wrestling backdrop to the novel.

Bruegel’s painting is a coulage depicting conflicting values associated with the period in the Christian religion known as Shrovetide, the 3 days of celebration and excess culminating in Ash Wednesday which, in turn, precedes Lent or 40 weekdays of self-denial leading up to Easter. Carnaval is personified as a gluttonous male; he is bulbous and lusty, with full codpiece and rides astride a barrel, perhaps a keg. He is followed out of the Blue Ship tavern by his retinue who revel in strange foods such as pancakes, waffles, sausages, and eggs and who decorate their costumes. And Carnaval carries a ‘lance’ – jousting with lances would have been a widely known form of sport/quarrel during the 16th century of Bruegel’s era – skewering a suckling pig:

Carnival’s counterpart is the haggard, female embodiment of Lent whom he faces in joust-like preparation. Lent is austere, gaunt, unhappy, and streams with her commonly-dressed followers out of the church at the right of the painting. Her ‘lance’ is a baker’s paddle with two fish-herrings on it (the Christian symbolism is blatant) and her followers carry much simpler foods like pretzels, mussels, fish, and figs. What we have in the painting is a confrontation of values – excess versus moral-physical-spiritual purity; they are extreme values and the painting, it is important to notice, is frozen, as though pause were pushed on the action, in that the “quarrel” between Carnival and Lent is not resolved. Instead, we are left to consider the extremes and ponder the folly of either end of the spectrum. In parallel, Irving uses wrestling terms and confrontations as his ‘painting’ to force us to look at a moral issue of the 1960s and 1970s, sexual excess, in this case mate-swapping. Irving’s use of the literary allusion to Bruegel’s The Quarrel is quite clever and very apt.

The two female characters in the novel, Utch and Edith are, in many respects, Carnaval- and Lent-like in body type and in personality. Utch is five feet, six inches tall and “rounded, full-hipped, full-breasted, with a curve at her belly and muscular legs…[and she] had a rump a child could sit on when she was standing up, but she had no fat on her” (p.29). By contrast, Edith Fuller, daughter of the very wealthy “New York Fullers,” was, says the Narrator, “the classiest woman I’ve ever known…relaxed, tall, graceful woman with a sensuous mouth and the most convincing, mature movements in her boyish hips and long-fingered hands; she had slim, silky legs and was as small- and high-breasted as a young girl, and as careless with her hair” (p.24). Where Edith was prep-school privileged, Utch was lower class, European stock, live-stock in fact, when we consider the details of her “second birth.”

When Utch was seven and living in Austria, the Russians invaded the country raping and killing almost at will. In fear for her daughter, Utch’s mother took her to a cow-barn and slit the throat of the largest cow still in its milking hitch. When it was dead, she rolled the cow on its side, cut open its belly, pulled out the intestines and carved out the anus. Then she told Utch to lie down in the cavity between the cow’s ribs and stuffed as much of the cow’s innards around her daughter; the rest she put outside to attract flies. Closing the belly flaps around Utch, she told her daughter to breathe through the cow’s anus and gave her a long, slim wine bottle filled with camomile tea and honey to drink with a straw. Wrapping the rest of the fly-infested intestines around the cow’s head gave the animal the appearance of being dead a long time and the mother left her daughter with instructions, communicated through the rectum of the cow, not to move until someone found her. Irving is literally visceral in his extended description of this event (see pages 11-13) and it is reflective of the whole novel’s tone of bittersweet irony that the person who finds and ‘delivers’ Utch – her real name is Anna, but Utch is Russian for calf – is a Russian man, Kudashvili. How much more viscerally ironic could the name-ending -vili (villi are the finger-like, nutrient-absorbing projections that line the small intestine) – be!

Utch is as earthy and as lusty as any of Carnaval’s followers in Bruegel’s painting. She ‘has sex,’ she does not make love and her ideal revenge when finally rejected by Severin (with whom she thinks she has fallen in love) in the mate-swapping is to rape him in his motel room at the national wrestling championships. Over-riding her vengeance and a constant quest for her throughout her adult life is to “have orgasm.” As the Narrator informs us, “When she was cross, Utch was fond of reducing the world to an orgasm” (p.23). Her first quest following the break-up of the foursome is to cure her main problem – “I can’t come” – a deficiency she rectifies by taking her husband to Severin’s wrestling room and forcing him to have sex with her. Utch adores wrestlers, particularly wrestlers’ bodies; the body of one black wrestler, Tyrone Williams, a 134-pound student in the same weight class as her own, is one about which she fantasizes almost constantly. Thus, Utch is bawdy, lusty, Carnaval-like. And hers is the character critics of this novel single out as vacuous, unbelievable, and undeveloped by the author. Perhaps, but I think that Irving uses her just as both the Narrator and Severin use her – for sex – and I think that she foreshadows some of Irving’s more well-developed female characters in his later works. At the end of this novel, Utch alone takes steps to heal herself and her life.

Edith is more refined, more in the tradition of Lent. She is a would-be writer who is really a well-trained art historian. She too liked wrestlers’ bodies especially those “with no asses, with small legs. Severin was like that” (p.87). Independent and very intelligent, she is the perfect foil for Severin and she is very drawn to the Narrator, the successful novelist. Where Severin and Utch dive into unbridled sexual encounters in the tradition of Shrovetide excess, Edith and the Narrator spend hours talking about writing either before or instead of having sex. It is Edith who recognizes that this level of intimacy is “the worst kind of infidelity” (p.195), much more so than mere sexual trysts. In point of fact in the novel, the whole sexual-marital experiment of mate-swapping is engineered by Edith and willingly supported by Severin. The latter had an earlier intimate affair with a dancer, one Audrey Cannon and it is that betrayal of excess that leads to Edith’s edict to Severin, “I’m going to get a lover” (p.204) and her pronouncement, “But now I’ve got this leverage on you” (p.204, underlining mine). Revenge she gets when at the end of the novel, Edith tries to seduce George James Bender, Severin’s star wrestler at the nationals; however, Bender cannot achieve an erection and Severin walks in on them trying to solve that problem. Out of apparent humiliation and remorse, Bender loses the final match the next day and Severin resigns from coaching. Where Severin languished in his affair with the literally-crippled Audrey Cannon (she ran over her own foot with her own lawnmower), Edith figuratively cripples Severin’s best wrestler ever and his greatest chance of winning a national championship. She tells her husband: “Now we’re even, if you still think being even matters” (p.228). The irony is that Severin only went along with the mate-swapping in the false hope that this would allow Edith to get even for his affair. Such one-up-personship is fitting in his wrestling world.

Edith then, is less the pure Lenten embodiment of austerity than Utch is of Carnaval. It is as though there is something in Edith that wants out, as though Irving cannot accept the excess of Lent or pure restraint. Edith, comparable to Utch, is not very well developed in the novel. Her husband, Severin, by contrast is fully characterized by Irving. In fact, it is Severin who is the lynch-pin to the whole novel and its wrestling motif.

An associate professor of German, Severin continually defines himself with lines like, “Yes, I coach wrestling”. A runner-up in the 157-pound weight class in The Big-10 wrestling championships at Michigan State, he more or less inherited his college coaching position after the untimely death of his predecessor. Like Irving, Severin beat wrestlers much better than himself because, as his former coach stated: “But he was one of those who kept coming. He just kept coming at you, if you know what I mean” (p.19). And the sexual connotations of the word, “coming” are not lost on readers. Severin is a source of both revulsion and attraction for the Narrator who gives Severin the most thorough description of anyone, even more than Edith whom the Narrator adores:

[Severin was] a man whose shortness stunned you because of his width, or whose width stunned you because of his shortness. He was five feet eight inches tall and maybe twenty pounds over his old 157-pound class. The muscles in his chest seemed to be layered in slabs. His upper arms seemed thicker than Edith’s lovely thighs. His neck was a strain on the best-made shirt in the world. He fought against a small, almost inconspicuous belly, which I liked to poke him in because he was so conscious of it….He had a massive, helmet-shaped head with a thick, dark-brown rug of hair which sat on top of his head like a skier’s knit hat and spilled like a cropped manover his ears. One ear was cauliflowered and he liked to hide it (p.25).

The “cauliflowered” ear refers to the ubiquitous wrestling injury known as wrestler’s ear or perichondrial hematoma, is a deformity caused by blunt trauma to the outer ear. It occurs as blood accumulates in the pinna that can disrupt the blood supply of the healthy cartilage and culminates in a fibrosis. It looks like this:

Severin is an enigma to the Narrator who could make little sense of a man divided between wearing headphones to learn German in a language lab and earguards to spar on a wrestling mat. Severin is rest-less, a rest-less wrest-ler, sometimes inflicted with insomnia. He even moved “restlessly…with the grace and spring of a bizarrely muscled deer” (p.43) and he behaved and looked more like a friendly animal, a “baby bear” (said Edith) who could not keep his hands off anyone with whom he talked; he mauled people in conversation, men and women without any apparent sexual intention. Utterly unlike the Narrator, “Severin Winter would not yield to anything” (p.189). Instead, he confronted, he fought always needing to be the “driver” (as in drive to the mat), the controller in any activity. As Irving states in The Imaginary Girlfriend:

“Wrestling is not about knocking a man down – it’s about controlling him” (p.13)

Severin then, must be in control. Cocky, aggressive, egocentric – “a wrestler’s ego seems to stay in shape long after he’s out of his weight class” (p.19 of Marriage) – and explosive were the adjectives used to describe Severin by the Narrator. But when Edith catches Severin frolicking in the pool with Audrey Cannon late at night (p.200), she notes that Severin and Audrey were “graceful and playful as seals,” a side of Severin and of wrestling she and the Narrator do not know. Severin’s verbal refrain echoes throughout the novel, “I have to go to the wrestling room” and he is the “mother” in nurturing and caring for their two daughters. The Narrator can never quite resolve the paradox of Severin’s “thunkish aesthetics” and he keeps trying to jock-stereotype Severin with observations such as, “For a wrestler, Severin had a very weak handshake, as if he were trying to impress you with how gentle he was” (p.230). Of the four characters, Severin is least at quarrel between the Carnaval and Lent qualities in himself; he seems comfortable both at revelling in sexual and physical excesses and in abstaining, at least on his terms (control), especially if he could bring sex and life into the wrestling room.

All character development and the whole moral issue Irving forces us to confront centre on wrestling themes, metaphors, locations, expressions, and words. In the latter regard, the words “pinned” and “decision” reverberate throughout the novel in reference to wrestling, to sex, and to moral decision-making. Utch keeps telling and re-telling herself to have patience in the early rounds of her bout with learning the English language. We the readers are constantly reminded of the tag-team-like exchanges in the couple matches/matching. Severin labels everything by weight class; for example, a “118-pound novel” is only a mildly successful novel, not one of significant weight. When the Narrator chides, “it must be nice, Severin, to involve yourself in a field that’s changed one pound in ten years” (157 to 158), Severin quickly retorts, “What about history? How many pounds has civilization changed? I’d guess about four ounces since Jesus, about half an ounce since Marx” (p.27). These allusions to and metaphors about wrestling seem more an undercurrent than overdone, more like subliminal advertising continually carrying the plot and character development. So too the sexual-wrestling imagery where couples are described as “going to the mat together” (p.150). When Severin wrestles with himself about entering the wrestling building to make love with Audrey Cannon, the Narrator describes him outside the edifice where “he circled…he stood…he crouched” just as a wrestler might do in stalking and measuring his opponent in a match.

Not only does Irving himself love wrestling, his characters underscore his love for the whole process and ambiance of wrestlers and wrestling. Odious to the Narrator, Irving is graphic in his descriptions about the sport. In reference to one “leg wrestler” from Ohio State, we are told:

he was a black with a knuckle-hard head, bruise-blue palms and a pair of knees like mahogany doorknobs….When he rode you with a cross-body ride – your near leg scissored, your far arm hooked – Severin said Jones cut off your circulation somewhere near your spine (p.18)

The Narrator himself could encapsulate half-truths about the physical appearance of wrestlers:

I recognized their hipless, assless, bowlegged walk, and their shoulders crouched awkwardly alongside their ears like yokes on oxen. (p.209)

Wrestlers were “funny, stumpy-looking figures” and “when they finished exercising they’d make for the weight room, turn up the thermostat and roll around” (p.187). To the uninitiated, wrestlers are virtually impossible to comprehend; they defy convention and definition. To Edith:

How crazily committed all Severin’s wrestlers looked to her. They seemed hypnotized by themselves, drugged in ego, which unleashed the moment their physical frenzy was peaking. It was too loud, too serious, too intense. It was also more struggle than grace; though Severin insisted it was more like a dance than a fight, to her it was a fight (p.87)

Irving is tender in getting to the heart and the heat of wrestling. He has his Narrator describe wrestlers’ early season workouts:

They lumbered and rolled and carried each other around in an almost elderly fashion. Some of them, tired from running in the woods or straining against the weightlifting contraptions, actually slept. The came to this hot-house [sauna, usually, a place to try to shed pounds to make their weight class] wearing double layers of sweatshirts with towels around their heads, and even as they slept they kept a sweat running. Tight against the wall and in the corners of the room where they would not accidentally be rolled on, they lay in mounds like bears (p.180, brackets mine)

Severin declares that he loves the wrestling room, one of only very few times that I could find the word, “love” actually used in the novel. His was a room “glaringly lit with long fluorescent bulbs” with “two roaring blow-heaters and its own thermostat…walls padded in crimson matting and from wall to wall it was carpeted with crimson and white wrestling mats” (p.75). And how Carnaval-Lent-like was Severin’s wrestlers’ procession ritual through a long tunnel to the wrestling area for a meet. Severin

would take his wrestlers through the long connecting tunnel to the new gym….Everything echoed in the tunnel. Winter would kill the light as he went. An occasional squash player would holler, “Hey, what the fuck!?” and open his cell. The effect of the wrestlers in single file, solemn in their robes and hoods (Winter’s choice), was quieting. Timidly, the squash and handball players often came out of their cells and followed the procession. It was a rite.

At the end of the dark tunnel procession, the coach threw open the doors to the bright light and yelling fans. Critics have labelled the whole thing more trite than rite given its re-birthing connotations; however, it seems more in keeping with the carnavalesque procession from Bruegel’s painting and more an echo of that aspect of the novel than it does any re-birthing ritual. And the same echo reverberates later in the story when Severin lustily leads Utch through the same tunnel:

It was midnight when he led her through the dark corridors; he knew every turn. They dressed in clean wrestling robes, the crimson ones with the ominous hood. Like monks engaged in some midnight rite, they walked through the fabulous tunnel; he kissed her; he felt her under her robe (p. 76)

There follows three pages of description of their love-making all in wrestling terminology and even in match-format that is indeed erotic in effect.

Unaccustomed to the conventions of wrestling but still a mirror of the wrestling undercurrent, Edith and the Narrator are uncomfortable with having sex prone so Irving describes their sex in upright-wrestling format in the shower, often culminating in a free-fall ending on the shower floor. And the wrestling-sexual encounters draw us back into the Carnaval-Lent confrontation with the swapped partners’ food of choice: the Lenten-like Edith/Narrator include only wine and cigarettes in their austere rituals whereas Utch/Severin leave trails of apple cores, spines of pears, cheese rinds, salami skins, grape stems, and empty beer bottles more emblematic of the hedonism of the gluttonous Carnaval.

Ultimately, each person in the quaternion wrestles with him- or her- self with respect to the moral issue of mate-swapping, just as Irving forces each reader to debate its morality as the novel proceeds (the same imposed self-confrontation technique Bruegel uses in his famous painting). The 158-pound marriage among the four people never works because there is no relationship among the four people. “It was often awkward when all four of us tried to have a conversation,” the Narrator states. Thus, unlike wrestlers, they never really engage, they just kind of couple off in sexual-sparring. If anything, they cop out of facing the morality of the issue and just verbally quarrel-spar in pale reflection of September wrestlers. The four are really indulgers in a rare pentathlon of Carnaval excess – “cooking, eating, drinking, wrestling and fucking” (p.105). It was tag-team sex and very much like tag-team, faked pro wrestling, it was devoid of substance, a sham for presumed entertainment value.

Irving leaves the reader to ponder the healing process, post-season, from the 158-pound marriage: Utch achieves some measure of self-realization and takes her children back to Vienna to recoup; the Narrator tries to get Bender to tell all about Edith as “the best-looking piece of ass in all of Vienna”; Edith and Severin also return to their meeting place, Vienna, to establish, presumably, some kind of order in their lives. All the while, Irving placed dark contrasts to the physicality of wrestling and love-making with two sinister gangsters in Utch’s childhood retinue (along with a mysterious man with a gaping hole in his cheek). Severin was tutored in his childhood by two old “knights,” both Olympic wrestlers from the 1936 Games and he had a mother who posed nude in postures of masturbation for art-works which were later hung by Severin over his and Edith’s bed. The four children remain background figures like the children do in Bruegel’s painting until two of them are seriously injured when the shower door – the same door of Edith’s and the Narrator’s “wet love-nest” – shatters while the children are bathing and shards of glass are embedded in their skins. This we take to be Irving’s sharp reminder to shake the foursome back into some level of responsible morality. And finally, Bruegel’s cripples (in the painting) are invoked by Irving in a cider-press amputee who hobbles toward Utch in Vienna at the end of the novel like “a stumped puppet, an amputated acrobat”, a grim reminder of life’s less carnavalesque possibilities.

The wrestling motif, the images, metaphors, analogies, and allusions work very well but not outside the context of Bruegel’s painting. All of Irving’s first four novels contain these common elements: Vienna, a small New England college town, bears, marital infidelity, the protection of children, violence, death, and wrestling. Of these common elements, wrestling is the least explored and least appreciated for what it reveals about human nature and for what Irving unravels about wrestling-as-sport and wrestling-as-life-affirming and life-reflecting. I tumble home often to John Irving’s ‘riting and revel, in this case, in ‘reading and revealing what it’s like to w/’restle john irving.

Addendum

I wrote an academic article by the same title as this blog in the late 1990s and published it in the Journal of Sport Literature:

Morrow, Don (1997) Wrestling John Irving. Aethlon: The Journal of Sport Literature, 14:2, 41-51.

To my delight, the editors have selected this piece to be included in the 40th Anniversary issue of Aethlon due to be published later this year, 2024. And it just came out (July 2024; the journal itself is a year or so behind publication schedule so it is listed as Fall 2022 / Winter 2023 but it is the 40th anniversary issue). Here is the first page of the table of contents; lo and behold Wrestling John Irving is the # 1 featured article:

Uncharacteristically or uncommon among academic journals, authors own the copyright to their Aethlon-published articles. Thus, I was able to use my publication freely in composing this blog. For teaching purposes in my Sport in Literature class, I updated the article in 2000, a few years after Irving published his memoir, The Imaginary Girlfriend. Finally, the points of analysis, for the most part, are my own. General works I did consult were these ones:

Globe and Mail, Toronto, 20 April 1996, p. C29 (review of The Imaginary Girlfriend).

Irving, John. The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada Ltd., 1996.

Irving, John. The 158-Pound Marriage. New York: Ballantine Books, 1974.

Irving, John. The World According to Garp. New York: Ballantine Books, 1976.

Marijnissen, Roger H. and Seidel, M. Bruegel. New York: Harrison House, 1984.

Miller, Gabriel. John Irving. New York: Frederick Unger Publishing Company, 1982.

Reilly, E.C. Understanding John Irving. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1991.