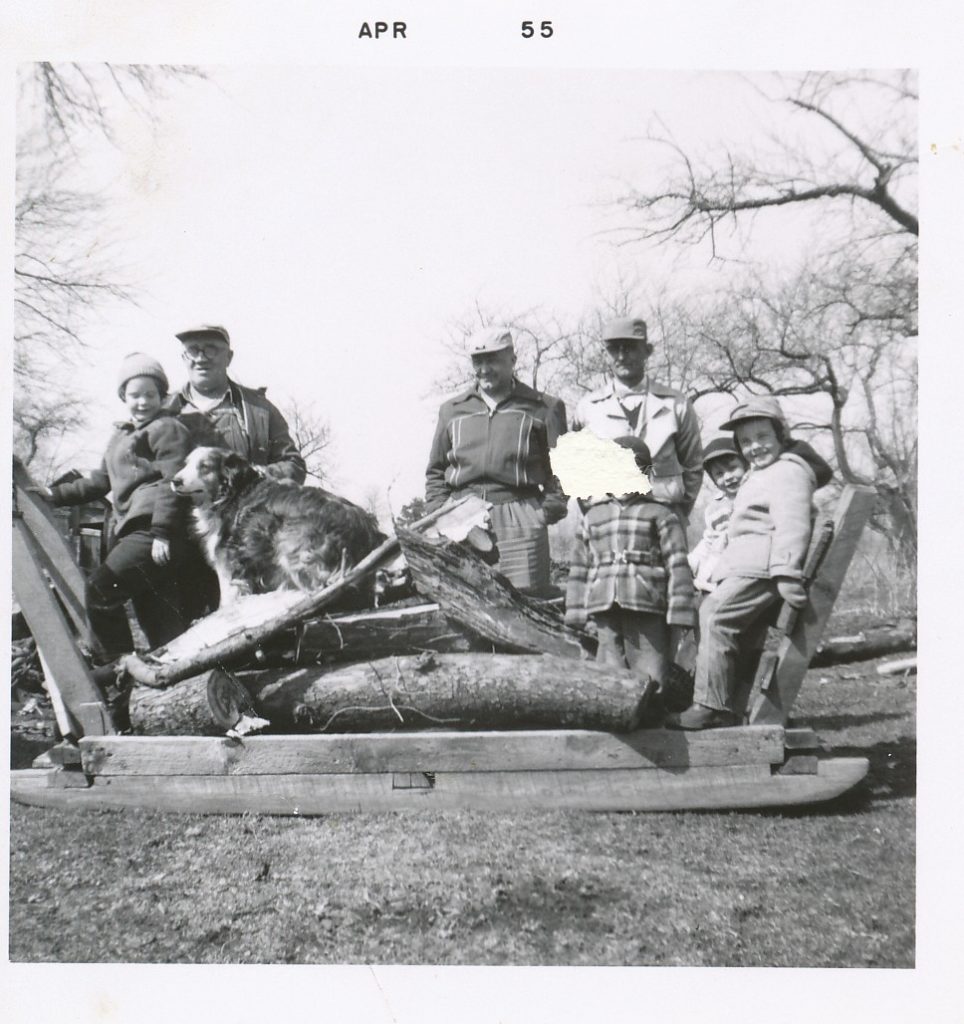

Woodcutter…the farm

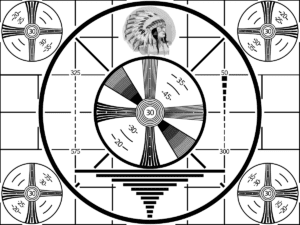

In the 1950s, everything was black and white, at least it seemed to be to me. TV was black and white; the test pattern on our television comes to mind, a black and white dartboard-like image, akin to a 45 rpm record encased in a 75 rpm record picture. The Indian-headed (why?) test-card was used, I now know, to calibrate black and white television sets. It seemed to stay on until programming resumed each day. It looked like this:

Life choices seemed to be more black and white. One of the aspects of my life that radiated in the colour of warmth was my time spent on my grandparents’ farm near Simcoe, Ontario. Nowhere was the feeling of being on the farm more richly described than in these lines from Dylan Thomas’s famous poem, Fern Hill:

And as I was green and carefree, famous among the barns

About the happy yard and singing as the farm was home,

In the sun that is young once only,

Time let me play and be

Golden in the mercy of his means,

When I first read that poem in high school, I understood it immediately and empathetically just from that second stanza alone. The farm, our farm was magic, my grandparents exceptionally common-folk and commonly exceptional human beings. Going to the farm was an adventure for my sisters and me. During what seemed like interminably long drives from our home to the farm, my older sister and I tried to out-search each other for the clue we were almost there – the red barn at the southeast junction of Highway 3 and the Turkey Point Road. Once sited, it meant we were mere minutes away. Looking back today, from a place of privilege and abundance, the farm was basic and yet, though we may not have had everything we wanted, we certainly had everything we needed.

There was no running water; two metal pumps in the kitchen had to be primed with a glass of water, replenished for each subsequent prime, and then pumped to produce water. Warm water came from a pot suspended above the stove always ready to be dipped into the cistern (its aqueous content too had to be replenished regularly from the pumps) on the wood stove, and the latter was the only cooking appliance. The toilet was either a chamber-pot under our beds for night use or the two-seater outhouse about 40 feet from the east side of the wood-shed. Beside and a few feet away from the outhouse and mirroring its structure in size was another shed where ashes from the stove were dumped and then used for soil enrichment, rose-bush growth, and I think for making candles. And the wood-shed had to be stocked with logs brought in from the adjacent small woodlands via the sled depicted in the image at the top of this blog. One of my jobs was stock-piling split-logs in the woodbox beside the stove, a daily chore that was just natural, part of the farm-mystique; the technique was to load as many logs as possible onto one bent arm, hold the top-most log with the other hand and then, climbing the precarious steps, to open the screen door into the kitchen without dropping any logs. Two large, round metal tubs and a wash-board were used for doing laundry; one of those containers served as bath-tub, set up in the middle of the kitchen on bath-night, always Saturday.

At the farm, we ate like royalty, or so every meal tasted like to me. Entrenched in my memory is one staple dinner meal, noodle soup whose stock came from the slow simmering of a chicken carcass, the remaining meat and fat eventually falling into the broth. The actual noodles were made from flour and eggs, the concoction rolling-pinned by Gram into a large flat, kind of doughy mass, then cut into strips and squares; the noodles were allowed to dry for some period of time and then were mixed into the broth and later served to us, liberally salted as I remember. Interestingly, all chickens we ate were ‘harvested’ live, that is, one was selected from the chicken coop, then killed with an axe chopping the head off at the neck on large block of wood used just for that purpose. I have distinct recollections of the headless chicken running a few steps before its nervous system quit working. We had to pluck the feathers and then wash the body. It never felt like anything but the way it was done, on the farm.

Not a very flattering photo of Gram…likely one from the late 1950s. A better one is this one in August 1967 on the occasion of my sister, Sandi’s wedding

My dad – as resplendent as I remember him – is on the far left and Gram is on Sandi’s right side

My grandmother was the epicentre of the farm. Affable, loving, kind, and extremely hard-working, it was she who made the meals, took care of my family and often my cousins for days, sometimes weeks at a time. In the summers, our most frequent visiting season, she tended the two huge gardens – one a flower garden planted with multi-coloured gladiolas or “glads,” as she called them, and a phalanx of other flowers which she sold to all kinds of people who just seemed to show up to buy them. The other garden was for fruits and vegetables. We picked strawberries for meals, served coated in sugar for desserts in a large glass bowl. And raspberries grew in cultivated bushes along the fence adjacent to the garden. Vegetables were harvested in what I now assume were large quantities; we carried bushel baskets of carrots, potatoes, turnips, and other “winter” vegetables into the kitchen to the adjacent pantry. In the latter room, on the floor near the far end, was a kind of trap-door, a full door, flat on the floor which, once-opened by lifting and propping it sideways perpendicular to the wall, lead to a dugout basement called the root cellar. In that dark, unheated, and kind of dank, muddy-smelling room, rectangular bins, angled downward back-to-front for easy access, were filled with the vegetables picked from the garden and kept stored for winter meals. All meals were prepared on Gram’s cast-iron stove – pictured below – constantly wood-fired (the wood stored in the wood-box to the right of the stove, replenished by grandchildren daily from the wood-shed) warmed water in the cistern on the right hand side. I cannot begin to imagine how much work it was for Gram to cook all meals on that stove, with no temperature gauge, do laundry (see the clothes’ rack and stacked, folded clothes behind her), prepare baths for us…no running water, amazing! In the summer, several streamers of sticky fly-paper hung from the kitchen ceiling to capture flies – imagine those yellow strips coated with dead flies…all normal to us. And well do I remember the patterned plate (lower left corner) and in my perception, the sumptuous meals we so enjoyed on that tableware.

Gram made us popsicles from Freshie or Kool-Aid poured into ice-cube trays; once semi-frozen, she stuck a toothpick in each cube to be used as a holding stick when finally frozen; if she forgot to do the toothpicks or remembered too late to insert them into the solid cubes, we used waxed paper to cradle the icy treats. Feral cats drank from grey-blotched, metal pie-pans of milk she left in the woodshed when she went out in the morning to feed those critters as well as to deliver bread-crumbs to the birds that she hailed with “here chicka-dee-dee-dee.” My grandmother’s husband, the man I called and knew until my teens as my grandfather, was Bruce Card. My genetic grandfather was killed in World War One – see more info about Lorance Thomas Morrow in my Re-membered blog. I didn’t make the connection that Bruce’s last name was not the same as ours; it likely never crossed my mind. We knew him by no other name than as ‘Stinky,’ not Grandpa or anything else, just Stinky and I know not the origin of that term of endearment. Stinky is the man at the far left of the woodcutter-sled image atop this blog. The sled itself was horse-drawn, by Dolly and Queen, the only barn-stable residents I recall. My father is the man in the centre and my Great-Uncle Louis, Gram’s brother is the other adult. I am the boy on the far right and the other 3 children are my first cousins. The dog, beloved among us, is Nipper (who slept always at the back of the stove). Below are Gram and Grandpa, perhaps on their wedding day…

A carpenter by trade, Stinky was a gentle man who spent endless hours with his grandchildren. We went with him in the early mornings when he taught us how to fetch eggs from under hens in the squawking chicken coop. Always clad in overalls, usually shod in high-cut leather bedroom slippers, and almost always smoking a self-rolled cigarette, I remember his calloused hands, some of his fingers bearing yellowed, hardened corns, likely from the pressure of constantly working with his hands. In the garage were his trade tools, hand-saws, hammers, folding wooden tape-measures riveted at various joints to extend or retract the length, screwdrivers, all manner of open tobacco-tins used to hold various sizes of nails or screws, and scraps of wood and sawdust everywhere. The garage had a Yale lock on it as did the newer garage at the back of the property; both locks were winter-protected, each with a piece of leather or rubber affixed to the door overhanging each lock. Stinky’s truck, a black Model T Ford, if memory serves, had self-crafted wooden boxes affixed to its sides, presumably for carrying his tools when he was contracted to build barns or tobacco kilns. He designed, fabricated, and colourfully painted small, decorative windmills shaped like cartoon characters or flowers and sold them to the same farm visitors as came for the ‘glads.’ And he took us for coveted rides on his Allis-Chalmers, orange tractor that had to be started – its engine “turned over” – with a hand-crank at the front of the machine, as ‘we’ ploughed or tilled the gardens or took bales of hay to the horses. Sometimes he even let us drive the tractor by holding the steering-wheel knob.

I remember the cement water-trough, seasonally decorated with huge spiders laying wait in their webs, and complete with its own pump, near the barn, the trough used by Queen and Dolly to drink and perhaps utilized by other farm animals as well. The barn too was special to us, the ground level a storage place for farm implements, sometimes boats owned by my uncle Lloyd, and the pièce de résistance, the hay-loft on the upper floor, a forbidden place to play and hide. My cousin and I spent hours playing make-up games on the farm, cowboys, Zorro, the Lone Ranger, or building high-jumps, rarely watching television though I do remember listening enraptured to music or stories – likely even hockey broadcasts in winter – at the large, dark brown, vertical radio box (Philco, I believe, about 3-4 feet high) complete with the finicky black knob we turned carefully to find stations displayed in the reddish-orange back-grounded window, something like this one…

If we were really good, my cousin and I got to go to Uncle Louis (my Gram’s brother, picture on the sled at the top of this blog) and Aunt Odetta’s – I can still taste her home-made, caramel fudge – house in nearby Tillsonburg. Aside from the candy, the allure was to get up very early in the morning to accompany Uncle Louis on his bread route, delivering loaves and buns for Lewis Bakeries to homes and small stores in the area. Though not my uncle’s truck – his was dark green with a Lewis bread log – this is pretty close to its 1950s vintage:

Two long porches flanked two sides of the farm-house, one on the south side, a screened-in room only and the other, at the front on the west face, encased in glass; each spanned almost the length and width of the house, respectively; the screen porch was closed in the Winter. In warmer months, we spent more time on the screen porch, trying to learn to drink coffee with Stinky or eating meals at the huge table. Our bedrooms were upstairs, blue-hued stripes with a flowered wallpaper pattern in the boys’ bedroom, pink in the girls’ across the hall. In the boys’ room, we could crouch down on the floor to listen, through a vent in the stove-pipe hole, to the grown-ups talk – the farm house was partially heated by an oil stove in winter. Outside of the south side of the house adjacent to the west end of the screen porch, there was a large, yellow (I think) oil tank that stored the fuel-oil for winter. And for some reason, my grandparents had 2 or 3 of these kerosene lamps, something like this one:

We had hydro so I assume this was used for darker areas at night – perhaps for the root cellar – and/or for power outages. Kerosene oil was a specialized oil used for lamps; the little handle on the side adjusted the height of the wick such that there was no smoke and just the right amount of light emanating from the lamp.

Down the hall from the upstairs bedrooms was the attic containing endless treasures of old clothing and chests sitting on the rickety, wobbly wide-boarded floor. There was even a sit-able porta potty, just a dark-stained box with a hole in the top and a hinged door at the front. Inside was a simple chamber-pot, or more likely a tin gallon pail, and we were told repeatedly, the commode was to be used only for ’emergency’ bowel movements at night, with the threat of having to carry the pot to the outhouse in the morning. We were all too scared, I think, to go into the dimly-lit (literally by a string-pull single light bulb) attic at night, let alone staying there to use that ‘thunder-mug,’ as we called it.

And there were special nights spent sleeping outside in make-shift tents of blankets thrown over one of the 3 lower clotheslines – located east of the woodshed, behind the vegetable garden – and anchored by rocks to make an upside down V-shape; distinctly I recollect lying prone in front of our tent, head held in my hands, staring at one of the three lightning rods – back-lighted by a full moon – atop the farm-house. And I swung on the tree-swing near the front or west side of the farm or, pendulum-like, standing on the bottom frame-bar of the huge metal farm-style gate that spanned the front of the driveway waiting for letters to arrive from my dad. On adventurous days, Gram would drive us in her Plymouth, equipped with a 3-speed, steering column-mounted gear shift with which she seemed to struggle in clutching, often muttering her favourite phrase of disgruntlement, “oh, sugar-tit!” We would visit her friend’s house where front and back doors were left wide open to allow her goats to roam freely through her home, or, Gram would take us into Simcoe, perhaps for grocery supplies and always for ice cream at Caswell’s dairy store before the trip home. Why is it that decades later, I still know the farm phone number, 426-4504?

Very likely, I and we were naughty or there were rainy days or interminably hot summers at the farm, but not imprinted on my mind’s eye. Sadly still, I remember watching Nipper, in failing health, be put down by a rifle by one of my uncles. And yet, and always, I tumble home, time and again to the wonder of that black and white farm, my Fern Hill, my grandparents, and a childhood of splendour in the country.

. . . 2022 addendum

Drawn by memories and a curiosity about my grandparents, in the Spring of 2018 I visited the Evergreen or Lynedoch Cemetery where they are buried.

I knew about the village of Lynedoch – about 15 km southwest of Simcoe – from the odd mention in conversations with my grandparents – decoration day (adorning grave sites with flowers or plants) was an important annual event to my grandparents. I may even have mowed the cemetery lawn there when I did mowing jobs with Stinky at other graveyards. Finding the cemetery took some sleuthing because I did not know it went by the name Evergreen. When I did learn the new name, I remember instantly thinking about and making a non-existent connection to Nicholas “Evergreen” Hughes, revered founder of the Montreal Snowshoe Club in 1843 (see my Tramps blog re Montreal snowshoeing stories and this entry in the Canadian Encyclopedia). Unexpectedly, my visit to the Lynedoch cemetery turned out to be a very inspiring experience for me.

I knew that both my grandfather, Bruce Card (1895-1962) and grandmother Mary (née Dawson then Morrow) Card (1897-1974) were interred in Lynedoch. I could not bring myself to attend either grandparent’s funeral and am sad now that I was not able to go. In 1962, Stinky died on the farm of a massive heart attack. It was in the Fall of 1962 just after we moved from Exeter to London and I started grade 9 at Beck Collegiate. My dad told me in the living room of our home in Dundas street; unable to speak, I just went up to my bedroom and lay down. As my cousin Rick related to me, apparently Stinky got out of bed early one morning, experiencing chest pains, said “sorry, Mary” and dropped dead. It must have been so devastating for Gram, outliving two husbands in her lifetime (her first husband, Lorance Thomas Morrow was killed at age 23 in the First World War – his story is told at my remembered blog). My grandmother went through dementia in the last few years of her life and died in 1974 when I was in Edmonton doing my doctorate. Rick honoured her by agreeing to be a pall-bearer. I wish now that I had the financial means to get home for her funeral. In truth, it took almost two decades after my mother’s death in 1957 before I was able to attend any funeral. My experience as an 8-year-old-boy of touching my mother in her coffin unaware that she would feel cold really, really impacted my ability to be with death and deceased persons. And I could not abide the smell of bouquets of flowers for many years, a fact I attributed to the overwhelming floral odours permeating the funeral home at my mom’s visitation (I could not go to her funeral…just couldn’t).

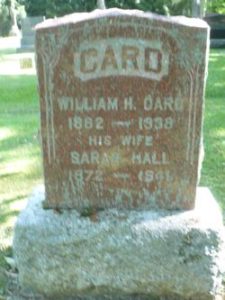

Thus, my trip to Lynedoch was one borne of a desire to pay my respects, to re-member my grandparents. There was no map or legend for finding grave-sites once I did manage to find the cemetery itself. It was a somewhat cool Spring day and I was surprised that Evergreen was fairly large for such a small community. Curiously, I found the ‘Card’ headstone within about 2 minutes, as though I were pulled to the site. The experience was eerie and palpable. I read the one side of the Card headstone, my Grandpa Card’s parents…

Within seconds, I realized the name of origin, “Hall,” was the last name of my Uncle Lloyd and Aunt Twila, owners of the first farm where I hung kiln in tobacco harvest. Their son, Brad, my cousin who often visited and played with Rick and me, was killed in a motorcycle accident in his late teens. I had never really connected the name Hall to Card and/or Morrow! And then I went around to the other side of the gravestone:

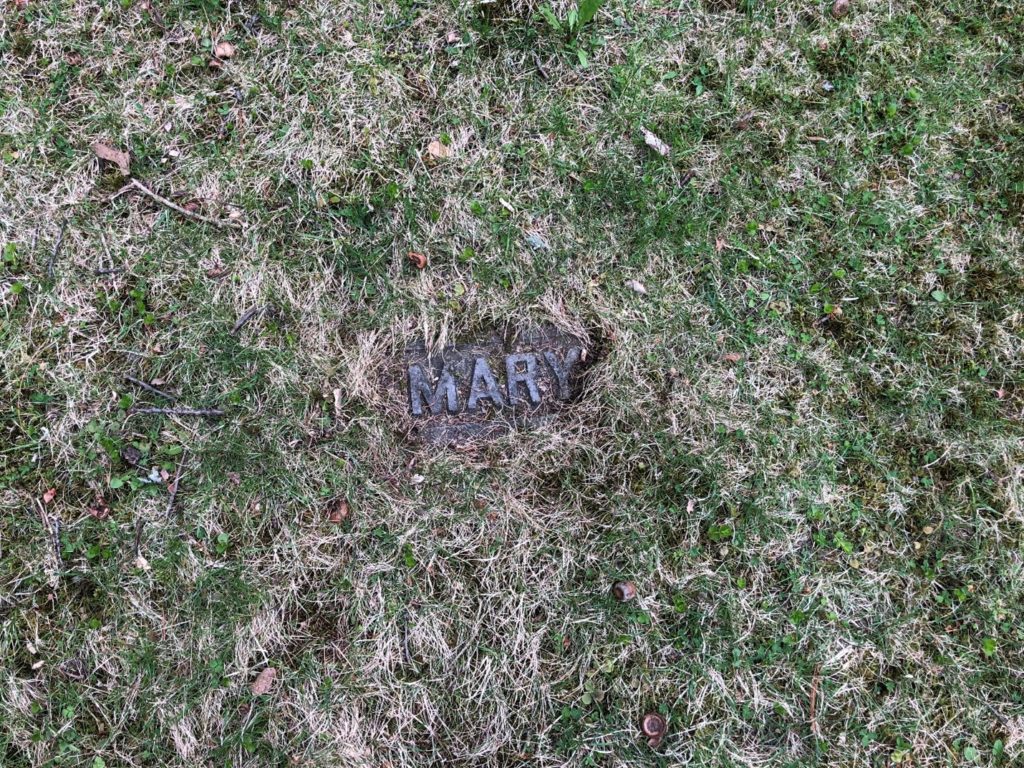

I found Gram’s grave marker…

but could not find Bruce’s anywhere. Then I just started to shake, as though I were chilled to the bone and I don’t get cold and it wasn’t that cold a day. It wasn’t scary or unbearable, just odd, a complete cold passing through me. Instantly, I thought of the legendary Sam MGee, in Robert Service’s famous, The Cremation of Sam McGee and the indescribable, intolerable cold Sam felt in the winter gold fields around Dawson City; I felt Sam’s cold. And, we, my grandparents and I used to go the “cold storage” at the small store about a mile south of the farm; you could walk into the freezer area to retrieve frozen meets (there was only a small fridge with a tiny, always frost-lined freezer at the fridge top on the farm) and the cold I felt at Lynedoch reminded me then and there of that cold storage, sort of dry-ice cold. As I stood there shaking, I was trying to take pictures and looked down to see what looked like a small stone in the ground. Turns out, I was standing on Bruce’s grave-marker…

It had completely overgrown with sod about 2 inches thick. So, I excavated it …

There was a gardener I met when I came into the cemetery but he didn’t know how to find particular head-stones. As I was leaving, he asked if I had found the Card headstone and I told him yes and showed him Bruce’s excavated marker picture and I asked if he would try to keep it uncovered. I said it might not seem like a big deal but to family, it was important and he said he understood and would look after keeping it uncovered. In my heart, I wanted their markers of life to be just that, visible markers of lives well-lived, of cherished family, man and woman who so warrant being remembered and honoured.

I left Lynedoch that day feeling connected, maybe re-connected to my grandparents in an almost sacred quest and experience. As I drove home, I thought about my years on the farm; harvests, both literal and metaphorical; Stinky-times; and the deep love I felt and still feel for both of them. I literally stumbled on their grave-markers and marvel at the stumble-tumblehome irony.

This Morrow family geneaology 2018 (added here in November 2022) provides documentation about the Morrow and Dawson family names, relatives, and ancestors. I don’t have the same information for the Card family.