Whirly-glows

For me, Christmas pretty much always has been steeped in traditions, rituals, and kind of living tableaus of memories anchored in smells, tastes, sounds, and emotions. Growing up Protestant in the United Church of Canada, I did know what Christmas was supposed to mean in the Christian religion. And yet, during the 1950s Christmas was just chock full of secular, celebratory events that seemed to overshadow or subsume the religiosity of the annual event. Perhaps this word cloud encapsulates the admixtures of Christmas-time meanings….

It seemed to me as a boy that the richness of Christmas was akin to this word cloud in that there were so many layers to the word, the holiday, the busyness, the joy, singing, gathering, presents, trees, families, and most of all, a kindness of human spirit that grounded the exceptional circumstances of Christmas. As I recollect it now, without intention (at least for me), the event was so exclusive, or at least, not inclusive; we did not respect diversity or equity in celebrating Christmas, not out of intention but out of ignorance. In Centralia, in Trenton, in Exeter, the town epicentres of my 1950s existence, I just assumed everyone celebrated Christmas. We were, I was insulated, White, and privileged, captivated by everything attached to this holiday. Even John Lennon’s “And so this is Christmas” released in 1971, though wrapped in ‘the war is over’ meanings, tingles with its lyrics, children’s voices, and haunting rhythms, all masking, for the most part, what Lennon sought to portray. In the same vein, I cherish my favourite rock band, Queen’s 1984 Thank God it’s Christmas, particularly the 2019 animated film version. That song reverberates even as I listen to it and I hear it like a soft, pulsating ear-worm each Christmas.

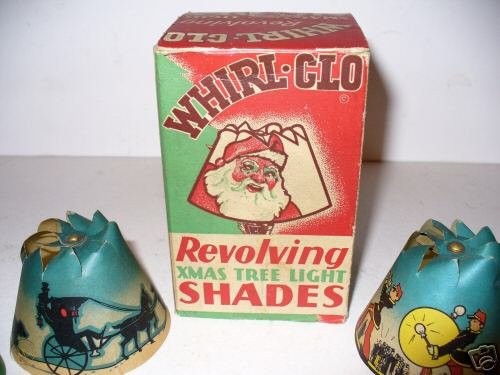

If I attach meaning to any single image from my boyhood era of Christmas times, it is cemented to one Christmas tree ornament we used each year – our whirly-glows. I’m sure that’s what we called them; turns out, they are Whirl-Glo by brand name…I prefer my boyhood nomenclature for them…

They were little paper lamp-shade-like structures, carousels, perhaps 2-3 inches in height and the same diameter. The top of each whirly-glow had a grommet into which the folds of the shade were collected. At the underside of that hub or centre was a small notch facing downward. That notch served as the point of insertion of paper cones or pin-caps – see the two pictured in front of the green box above – that fitted over a single Christmas tree light bulb. Each cap or cone had a straight pin pointing upward from the top of the cone; the carousel could be set at its centre-point on the cone pin-tip. Once the cone was set on a Christmas tree light – always Noma lights? – a deft finger swipe would rotate the carousel and when the lights were glowing, the carousels turned automatically from the heat radiating from each light bulb. Each carousel was decorated – reindeer and other images – that produced the illusion of movement as each mini-shade whirled slowly, the back-light giving visual relief to the moving images.

I don’t remember what images were on our whirly-glows; what I do recall is my absolute fascination with them watching them for minutes or just passing by the tree giving a furtive glance to the light-bulb circumnavigating shades. If a string of light bulbs were not working because of one bulb burning out thereby shutting down the current to all bulbs in the string, then the whirly-glows ceased to function. I considered it both a duty and personal triumph to find the offending bulb and reignite the string to reinvigorate the carousels.

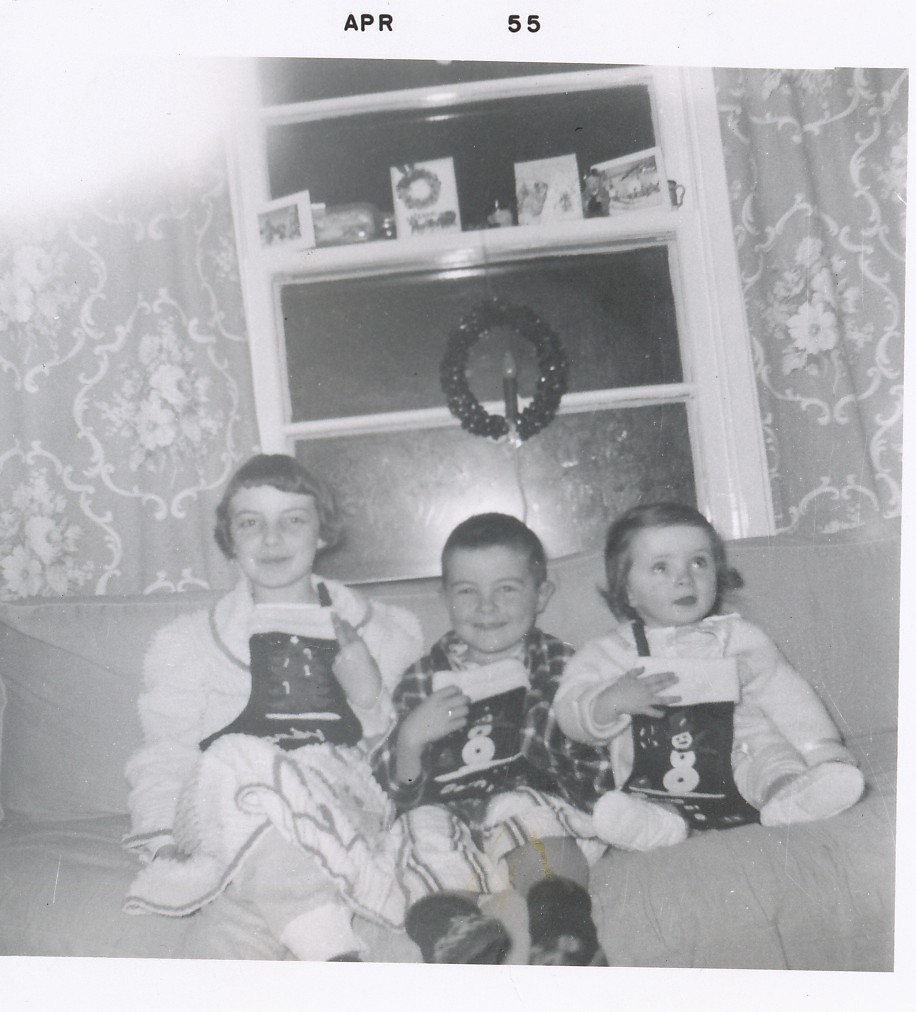

Our Christmas trees were always ‘real’ ones, lower branches removed, the trunk-bottoms sawed at a 45-degree angle to promote the tree absorbing water once set upright in the cast-iron stand, the stand, in turn, encompassed a bowl of water into which the sawed tree-bottom fit. Rarely, it seems did the stand support the tree fully; we had to wrap twine around the upper trunk and thumb-tack each end of the string to the wall or window frame to stabilize the tree. The earliest image I have of one of our trees are the two below with me on the left, my sisters Marnie and Sandi beside me. My best guess is it was 1954 and I was 5-and-a-half and we were living on the Air Force base in Centralia:

There were all manner of other decorations, pendant ones, balls, home-made ones from schools, decorative strings, reams of tinsel ‘icicles’ that I delighted in throwing at the tree in bunches over the more tedious one-icicle-at-a-time meticulous method, and probably an angel on the top but the whirly-glows just rendered the tree splendid.

So many elements became traditions around Christmas…stockings, for example, getting them out just before bedtime (I believe either my mother or her sister, my Aunt Jean made these stockings) – as in the image below of Christmas eve 1954 – and then hanging them for Santa Claus – I have always preferred the much more euphonious Kris Kringle – accompanied by cookies, carrots, and milk for him and his reindeer sustenance during his global, nocturnal revolution, the latter, an ultimate whirly-glow…

Even the window-suspended, electric wreath in the image above, a sorry decoration by contemporary standards but it was important in my childhood to my family. Christmas cards were omnipresent in our house, either on shelves, mantles, or mostly suspended by their folds on strings over bare walls or in doorways. Cards seemed to be the way in which families and friends, close or afar kept in touch annually in my parents’ generation via the brief card-greetings and ones containing annual family updates inserted onto or into the cards. Christmas presents were always dominant lures to the festive seasons. In my mind’s eye, I have a vivid recollection of one toy, a log cabin one like this:

It came, I think, in some kind of tube-container – from Lincoln Logs or Paul Bunyan Logs – not assembled and it seemed to suit my skills in fitting the blocks together right up to the green roof-top. Perhaps I linked it to the carpentry and building acumen of my grandfather, the roof of green reverberating the siding of the sheds on my grandparents’ farm – see my blog on Woodcutter..the farm.

It came, I think, in some kind of tube-container – from Lincoln Logs or Paul Bunyan Logs – not assembled and it seemed to suit my skills in fitting the blocks together right up to the green roof-top. Perhaps I linked it to the carpentry and building acumen of my grandfather, the roof of green reverberating the siding of the sheds on my grandparents’ farm – see my blog on Woodcutter..the farm.

Did we have relatives for Christmas? Probably. Did we eat turkey dinners, even more likely; I do smell-remember interminably long afternoons of dinner preparations, turkey bastings, peeling potatoes to be mashed. I think most of our actual Christmas days during the 1950s were spent at home; if we went to the farm in Simcoe, it would be after Christmas day. Sometimes, we went to my cousins at my Uncle Ted’s (a doctor, my mother’s brother) and Aunt Rita’s in Elmira. Aunt Rita specialized in making Russian toffee – a sweet mixture of butter, corn syrup, Eagle brand milk, and brown sugar – the recipe is here. When cooking, the candy, as it reached hard crack or whatever stage in the process, smelled like vomit for a short time, an odour I distinctly remember from my Elmira Christmas holidays. However, the taste was magnificent, a hard candy you sucked on until it could be chewed. Why “Russian” toffee? No idea but it seemed apt somehow. Many years later, I think, my father started to make his own Christmas candy, butter-almond-crunch, an addictive treat that was and remains far tastier than the Laura Secord version. For many years, I made it for my family; my sister Sandi still makes and gives away batches of it annually, having adapted Dad’s recipe slightly.

And so I remember my boyhood Christmases insulated by the simplicity of the black-and-white 1950s. These were times of light, literally, and lightness of being, the latter phrase I cannot use without ruminating on Milan Kundera’s sensuous novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being – except that mine was very much a bearable, cherished lightness of being, very likely embellished from 60 years’ passing after those days. Christmas remains a feeling or even more, an attitude of celebration, of giving, of receiving, of joy, of caroling, of festivity, and so much more – not an event, deeper somehow, more resplendent in its secular and spiritual aspects. And I cannot help but compare the feeling-times to Dylan Thomas’ first verse-stanza of Fern Hill:

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honoured among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daisies and barley

Down the rivers of the windfall light.

And today, older, I still feel the richness of those Christmas-y times and I tumble home to the revolutions of our whirly-glows, the epicentre of my memories of my own Dickensian ghosts of Christmases’ past and passed: