Dryden & The Game

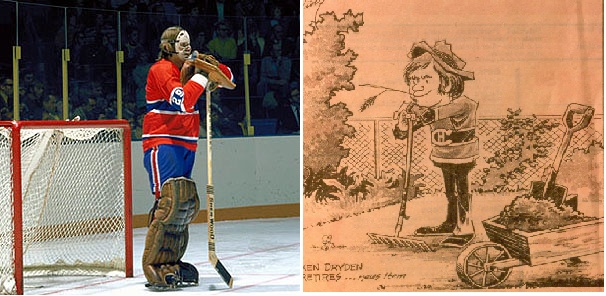

Ken Dryden, 1947-2025 – classic goalie pose on the left & fitting retirement-cartoon caricaturized by Ting

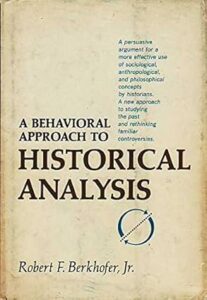

Ken Dryden died just a few days ago, on September 5th. Media and personal tributes abound and continue to do so for the affable gentleman who stood 6 feet, 4 inches in his prime. I admired his playing style and his skills as a goaltender for the Montreal Canadiens during the 1970s together with his role as goalie during the consummate 1972 Canada v Russia hockey series. As an academic, an historian of sport/s, two books stand out as the most inspirational to me. One was Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr.’s A Behavioral Approach to Historical Analysis:

My fascination with this work was Berkhofer’s insistence on the fact that we can never know what really happened in the past; historians create history, they do not re-create it. In one sense, history is the past but it’s unknowable in all its details, complexities. Historians interpret the past for us from the often fragments of artifacts and data that survive/d over time. As a historian, I tried to be conscious of this truism in anything I wrote, taught, and/or published. The other book that enchanted me was Dryden’s 1983 gem of a work, succinctly and poignantly entitled, The Game. I inhaled its contents and incorporated a lot of Dryden’s brilliant ideas in my sport literature and sport history university classes. In 2004, I began work on an analysis of The Game and ended up publishing my essay; its somewhat mellifluous title was, “Timelessness and Historicity of the game in Ken Dryden’s The Game.” As a kind of personal tribute and hockey hymn/him to Dryden, to honour him at the time of his passing, I choose to re-print my article here, updated and edited slightly and contextualized where appropriate. The numbers (green font encased in square brackets) are the Endnotes provided at the end of the blog’s text; these are not at all necessary to read but they are there just because I am an academic at heart and choose to document my facts and give due credit to sources. Some of the endnotes have additional content in them and some of that content might be of interest to readers.

In 2003, John Wiley Ltd. re-published Ken Dryden’s The Game as a special “20th Anniversary Edition.”[1] Originally published by Macmillan of Canada,[2] the 1983 work has become somewhat of a ‘classic’ piece of literature ostensibly concerning hockey, one of its most celebrated players, the Montreal Canadiens franchise, and an ‘insider-look’ at ice hockey à la Ken Dryden, five-time Vezina trophy winner as the National Hockey League’s best goaltender, and six-time member of Stanley Cup winning teams. Dryden states in his introductory paragraphs:

It was a book I couldn’t have written while I played [it was published 4 years after he retired from pro hockey in 1979]. It needed time. As it is with a game, I needed to wait for lifelong, career-long feelings to settle and sort themselves out. I needed to distance myself from things I had long since stopped seeing, to see them again. In the end, it turned out to be the kind of wonderful, awful, agonizing, boring, thrilling time others have described writing to be. One of those things we call “an experience.”[3]

It is my contention that the power and allure of what Dryden has written are derived from his perceptive, and in many ways, timeless insights into the whole concept of the game. Fittingly, it is his title. It is not, in fact, a book about hockey or a celebrated team in hockey or an era of hockey, or even any kind of autobiographical reminiscence of Dryden’s playing time (the 1970s) in the NHL. Instead, it is a rare and very sophisticated glimpse into the vibrant meaning of game as it is represented in one of game’s outer cloaks, the sport of ice hockey. The purpose of this paper then is to deconstruct The Game by using it as text for my analysis of the game concept. The book is, I believe, one of those subtle treatises that sneaks inside its readers’ bones because it speaks to one of life’s great metaphors, the game of life, compressed zip-file-like into one person’s learning/s from his experiences and introspections in and through a literal game. Think of all the ways the concept of game carries meaning – game of cards; game of chess; game of hide-and-seek; hopscotch and skipping rope; even playing lotteries is a form of game/gaming; in a hunt, wild game is about the chase, the thrill of the hunt. Sports’ games are but one form of game. It is in fact, the process of engaging with a game that enraptures, teases, tickles, tantalizes, infuriates, captivates, envelops, seizes participants – we suspend reality and give over to unnecessary obstacles. Solving a jigsaw puzzle is a game of engagement with sometimes thousands of pieces to the puzzle; we adapt to the convention and artificial ‘rules’ of jigsaw puzzling because of the allure to be in that process of solving the puzzle. The game is so much more than the activity itself – the people who play the game; the process of playing; the time between games; anticipating the game-playing etc. Thus, Dryden chose to write about his sport’s essence, its game, his game, the game of hockey, and the meaning it brought to Dryden’s whole life.

Concerning the significance of hockey in Canadian culture, there are two images I wish to discuss briefly to provide some context for Dryden’s text. First, there is the kind of Canadian imperative about ice hockey, the sport “invented” in Canada, eventually legislated federally as one of two national sports.[4] The first image is called Canadian Gothic and it is a stylized version of Grant Woods’ famous 1930 painting, American Gothic. The latter original artwork has been transformed electronically and otherwise into many variations including a parody of former US President Bill Clinton and his wife Hilary.[5] Just as American Gothic draws us to the ‘sour and dour’ couple, so too does Canadian Gothic draw us to the juxtaposition of the same facials against the backdrop of one of the most well know pieces of Canadian architecture, Maple Leaf Gardens, Anglophone Canada’s hockey shrine in Toronto. Instead of the original pitchfork implement, the old man in the picture carries an Easton hockey stick. It just seems such a perfect image to imply Canada’s hockey heraldry using an American classic[6] and it gets inside the viewer’s skin immediately.

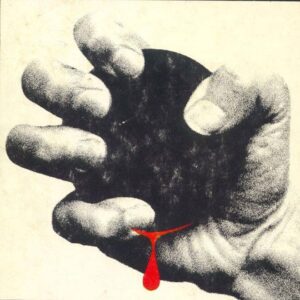

The second image is perhaps more obviously and directly germane to this analysis of Dryden’s book and its enduring message as a mollifiable paean to the game of hockey:

This is an image taken from the front jacket-cover of the book The Death of Hockey[7] published about 11 years before the original edition of Dryden’s The Game. It is difficult to imagine a more apropos and salient picture that so accurately embodies this book’s text. In the first chapter, entitled ‘The Canadian Specific,’ the authors proclaim that:

Like the ball games of the Mayan Indians of Mexico, worshipped because the arc of the kicked ball was thought to imitate the flight of the sun and moon across the heavens, hockey captures the essence of the Canadian experience in the New World. In a land so inescapably and so inhospitably cold, hockey is the dance of life, an affirmation that despite the deathly chill of winter we are alive.[8]

Following this first section, the authors turn their investigative and analytical attention to the ways and means that the Canadian life-blood has been squeezed out of hockey by such pernicious forces as the media, NHL player monopolies, commercialization to extremes, professionalization, and professional impact at all levels of the sport. The Death of Hockey and this haunting front cover image formed an important in-depth look at the factors inherent in reshaping the sport of hockey. Thus, Canadian Gothic and the blood-squeezed puck graphically symbolize the significance of the sport of hockey in the Canadian national imagination.[9]

Dryden’s book goes deeper into the fabric of hockey, I suggest, than any cultural representations, national enactments, or insightful analyses (such as The Death of Hockey or the more recent, Hockey Night in Canada: Sport, Identities and Cultural Politics[10]) of the sport. What Dryden does is take the reader outside of the “Canadian specific” and into the game itself. There is at least one important precedent to Dryden’s work, that of Jack London’s 1905 novel about boxing, The Game.[11]

London was an avid boxer and devout student of the sport; his book was first serialized in Metropolitan Magazine (April-May 1905). The story was heavily critiqued as unreal because its protagonist, Joe, is hit by a punch, falls to the canvas, and dies as a result of the fall. Regardless of its storyline, what is significant here is that London’s attention to the game of boxing foreshadows Dryden’s work. London’s ‘canvas’ is not that of boxing per se; instead, he writes to uncover the notion of the game. In the words of Joe’s lover, Genevieve, after she absorbs the shock of Joe’s death:

This, then, was the end of it all–of the carpets, and furniture, and the little rented house; of the meetings and walking out, the thrilling nights of starshine, the deliciousness of surrender, the loving and the being loved. She was stunned by the awful facts of this Game she did not understand–the grip it laid on men’s souls, its irony and faithlessness, its risks and hazards and fierce insurgences of the blood, making woman pitiful, not the be-all and end-all of man, but his toy and his pastime; to woman his mothering and caretaking, his moods and his moments, but to the Game his days and nights of striving, the tribute of his head and hand, his most patient toil and wildest effort, all the strain and the stress of his being–to the Game, his heart’s desire.[12]

London, of course, was a prolific author, perhaps best remembered for The Call of the Wild (1903). And clearly, his The Game is a novel whereas Dryden’s is more a treatise or a study. The parallel that I perceive is in Genevieve’s notion of the meaning of “the Game” to Joe, and by extension, to London who wrote passionately and prolifically about the great questions of life and death, the struggle to survive with dignity and integrity. That is, similar to Dryden, London sought to reveal the meaning behind the sport he loved, the game, [13] as he perceived it, which suffuses boxing and reverberates in “his [Joe’s] being.”

Dryden’s The Game received quite stunning acclaim. Consider some selected examples of the effusive popular praise:

~ “the sports book of the year, or maybe the decade, or maybe the century” ~ Globe and Mail

~ “a book about Ken Dryden, about Quebec, about the rest of Canada, and most of all, a loving book about a special sport” ~ New York Times

~ “one of the top 100 Best Sports Books of all time (# 9)” ~ Sports Illustrated

~ one of “the top 100 English-Canadian books of the 20th century” ~ University of Toronto Review

The Game was instantly likened to Jim Bouton’s trenchant examination of baseball, Ball Four.[14] In its more than 30-year existence, Bouton’s baseball exposé has sold more than five million copies, strong testament to its public appeal, “a book deep in the American vein, so deep in fact it is by no means a sports book,” as author David Halberstam proclaimed.[15] Ball Four was an insider’s view of the sport, an incisive look into the “corners,” sordid and otherwise, of baseball that was written during (or even ushered in) a period when ‘revelatory’ books on sport abounded.[16] Dryden’s book is quite singular and distinctly different from the exposé genre in that it goes more to the heart of hockey, its game-ness. In fact, in many ways, it failed to satisfy many hockey fans’ expectations because it was not about hockey.[17]

What is The Game about then? I suggest there are elements in the book that parallel words from a poem, A Dream, contained in Herman Hesse’s 1943 Nobel prize- winning work, Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game):

I traced once more the whole path of mankind,

And all that men have ever done and said

Disclosed its inner meaning to my mind.

I read, and saw those hieroglyphic forms

Couple and part, and coalesce in swarms,

Dance for a while together, separate,

Once more in newer patterns integrate,

A kaleidoscope of endless metaphors-

And each some vaster, fresher sense explores[18]

The book, loosely, is a story of an elite cult of intellectuals who occupy themselves with an elaborate game [ludi is the plural of ludus, the Latin word for game] that employs all of the cultural and scientific knowledge of the ages.[19] The master of the game – magister ludi – is Hesse’s Joseph Knecht, the narrator. I see distinct parallels in Dryden’s narration of his sense of ‘ludi’ in The Game. Somewhat obliquely, the “hieroglyphic forms’” expression in the poem is quite a sound, kaleidoscopic and metaphorical description of the motion in a game of ice hockey.

What is it that makes Dryden’s book so penetrating and so poignant an analysis of the game of hockey? One of the very clear factors is the quality of the writing and the writer. Thus, it is important to provide some context about Dryden himself. His years in the NHL and his championships have already been noted. One of the hallmarks of his own place in the pantheon of hockey is the fact that he is well remembered for his 4-game performance in the renowned Canada versus the USSR 1972 Summit Series[20]; in fact, that series and his performances in it really ushered him into his NHL career. Somewhat curiously, Dryden devotes very little attention to the 1972 series in The Game.[21] A graduate of both Cornell University[22] where he majored in History and of McGill University from which he earned his degree in Law, Dryden’s level of educational achievement, it seems logical to assume, goes beyond that of most NHL players.

Furthermore, as a trained historian, it is reasonable to assume that Dryden also wrote this book with a sense of time and place that would be rare for most athletes cum authors. In support of the latter assumption, Dryden’s sense of history and narrative are visibly and vividly apparent in his third book (Face-Off at the Summit, 1973, was his first), Home Game: Hockey and Life in Canada.[23] In the latter work, it was the stories about “people and places”[24] that compelled Dryden to collaborate on this book and simultaneously work on what became an award-winning television documentary series, also entitled Home Game.[25] And Dryden has published two more books,[26] neither directly relevant to this analysis. What is fundamental to my perspective herein is the fact that Dryden came to writing The Game replete with a distinguished career at the highest level of professional hockey; an enviable post secondary education that included historical training; an emergent sense of the place of hockey in his life, in Canadian (and North American) culture; and an intuitive knowing about the nature of the game itself.

Dryden retired from the NHL in 1979. This event prompted one cartoonist to capture the essence of the moment with this caricature (also used at the start of this blog):

The image[27] was/is especially indicative of Dryden’s trademark goalie posture and even more, his thoughtful and provocative gaze and evocative prose about the game. As he said about his retirement, “It is hockey that I’m leaving behind. It’s the game that I’ll miss.”[28] My perspective is that what magnetizes the reader to this book is not the hockey, not the lore of the locker room, not the tales of the players – it simply is not about hockey. Where Home Game (and the documentary) provides narratives for the Canadian hockey sporting metaphor, I contend that what Dryden underscores in The Game is the archetype that is the game – game time, our game, a game, game day, river game and so forth. By archetype, I mean more than prototype or pattern or original example; instead, I use the term almost in the Jungian sense as, “an inherited pattern of thought or symbolic imagery derived from the past collective experience and present in the individual unconscious.”[29] That is, the way Dryden uses the concept of game is as though it is a primary human impulse very much in the way that Huizingua, in Homo Ludens [Humankind the Game-Player], described the primary impulse of play.[30] There is something universal about the notion of game in human existence – we all know the meaning and feeling of game in whatever form we experience game/s – and it is this universality that Dryden portrays so skillfully as he perceived and felt it within his/the sphere of ice hockey.

Just as Jack London described about his boxing protagonist, “to the Game, his heart’s desire,”[31] Dryden ‘feels’ the game. Where Hesse’s Magister Ludi poem cited above suggests the nuance of his “kaleidoscope of endless metaphors,” Dryden’s work is a kaleidoscope of the game archetype. Bouton in Ball Four takes us into the locker room unabridged; Dryden takes us into the place we already know, into game-ness, a game, any game and even deeper into how the game is so alluring. The Game is seminal and important because, I believe, it grabs us like the mother-archetype – we know game as we know the universal concept of mother. The lens used by Dryden is the prism of hockey to see how we invent the game of life we play, hockey included. It is as though Dryden’s contemplative, trademark posture[32]

epitomizes his gaze[33] into the game, more akin to famed Canadian sculptor R. Tait McKenzie’s use of “athletic stasis” poses in his work – where the athlete is neither directly involved in the action and yet not uninvolved.[34] Indeed, the image forms the dominant part of the dust jacket for both editions[35] of The Game and it mirrors the subtitle of the book, “a reflective and thought-provoking look at a life in hockey.” Note that the last 4 words in that subtitle are not a hockey life but a life in hockey.

On the cover of the Canadian edition of the book, Dryden’s torso is encircled by the letter ‘G’ that starts the word ‘Game:’

The image here is the proverbial a-picture-is-worth-a-thousand-words. Dryden quite literally does go inside the game, through it and he takes the reader with him right from the lure of his first three well-chosen words, “I hear something….”[36] Structurally, there are ten chapters (nine of them titled after days of the week, from “Monday” through to the following “Tuesday” and an Epilogue chapter) to the book, plus a new “Overtime” chapter in the 2003 edition. The “days” are generic, emblematic of the game cycle; no day refers to a specific day anymore than the book refers specifically to hockey. Each chapter begins with at least one, often two epigraphs. For example, Dryden uses quotations from Brigitte Bardot (“I leave before being left. I decide”[37]) or Pierre-Jean de Béranger (“Our friends, the enemy”[38]) or William Butler Yeats (“O body swayed to music, O brightening glance / How can we know the dancer from the dance”[39]). The quotations do reflect the author’s eruditeness, without question; more significantly, they serve either as glimpses, almost compressed abstracts and/or they are woven into the meaning or theme of each chapter. The Yeats’ quotation prefaces chapter six, “Saturday,” which is a Montréal home “game-day.” Part I of that chapter focuses on the players (Yeats’ dancers) and their superstitions, their equipment, their moods, their “revving up,”[40] their routines; Part II is the dance, the game that “bogs deeper”[41] and the game that “warmed up in the dressing room and started in the middle.”[42] In short, the structure of the book matches its function, to get inside the game and make it manifest.

The image here is the proverbial a-picture-is-worth-a-thousand-words. Dryden quite literally does go inside the game, through it and he takes the reader with him right from the lure of his first three well-chosen words, “I hear something….”[36] Structurally, there are ten chapters (nine of them titled after days of the week, from “Monday” through to the following “Tuesday” and an Epilogue chapter) to the book, plus a new “Overtime” chapter in the 2003 edition. The “days” are generic, emblematic of the game cycle; no day refers to a specific day anymore than the book refers specifically to hockey. Each chapter begins with at least one, often two epigraphs. For example, Dryden uses quotations from Brigitte Bardot (“I leave before being left. I decide”[37]) or Pierre-Jean de Béranger (“Our friends, the enemy”[38]) or William Butler Yeats (“O body swayed to music, O brightening glance / How can we know the dancer from the dance”[39]). The quotations do reflect the author’s eruditeness, without question; more significantly, they serve either as glimpses, almost compressed abstracts and/or they are woven into the meaning or theme of each chapter. The Yeats’ quotation prefaces chapter six, “Saturday,” which is a Montréal home “game-day.” Part I of that chapter focuses on the players (Yeats’ dancers) and their superstitions, their equipment, their moods, their “revving up,”[40] their routines; Part II is the dance, the game that “bogs deeper”[41] and the game that “warmed up in the dressing room and started in the middle.”[42] In short, the structure of the book matches its function, to get inside the game and make it manifest.

More than anything, Dryden is so adept at letting the reader feel the game. Mere analysis or endless descriptions would have made the book tediously about hockey. The game gets inside Dryden’s skin and he constantly reminds us about the affective state of his consciousness concerning the game. Dryden’s feeling is both a sensation and an awareness of the game that moves around, within and through him. Ruminating on his post-game feelings as a player, when he was “still able to find joy in the game,” he states:

It is a different game from the one I played on a driveway twenty-five years ago, grown cluttered and complicated by the life around it, but guileless at its core and still recoverable from time to time.[43]

From his own affective awareness, he realizes that, “I like the feeling of moving”[44] and, as a goalie he can admit, “Yet I am often afraid”[45] and “you feel the sun slowly hemorrhaging away.”[46] And for elements connected to the game, such as the Canadiens’ dressing room, “it has the look and feel of a child’s bedroom.”[47] With respect to the feeling of a game, any game, he can convey the essence of the game in striking fashion. On the bus after the game, any bus after any game:

The bus starts up, the beer spills down, and words begin to flow. One by one, laser-like reading lights extinguish, one by one, tiny orange discs appear, glowing brightly with each languorous breath, as cigar smokers, with the world by its tail, settle into their mood. And slowly, as the bus turns from dusk to dark, the talk softens and runs out of steam. It is now when a game feels best, when bodies and minds clenched all day suddenly release and feelings gently wash over you. Lying back in my seat, my eyes wide open, I let it happen.[48]

The game is, in part, this affective component of and at its core. It is not confined to an/the actual game of hockey; it is beyond the arena boundaries and it can even be anticipatory, as it is for Dryden on Saturday, game day, during the first moments of the first period of play when, “the game that has occupied me all day is still far away.”[49]

Dryden almost personifies the game; to him it lives and breathes. He says, “the game will swing again, but not for long…it always swings back”[50] and, “I built slowly for the game…until the game and I became a fixation.”[51] There are a myriad of examples to illustrate his incarnation of the game:

~ “the game has grown up”[52]

~ “I couldn’t feel what the game felt like”[53]

~ “as it gets closer, my mind and body discover its rhythm and build with it toward game-time”[54]

~ “the game turns and moves to the center zone”[55]

~ “the game’s tempos, its moods”[56]

And it is not the purity of the game as a respiring or as an ethereal entity that preoccupies Dryden’s attention. He does realize quite clearly how the game can be taken out of its primordial existence and transmuted – debased, in may ways – to “an ad game, an image game, a celebrity game.”[57] And yet the game still lives and breathes beyond the pale of advertising attire or the egos that inhabit or better, infiltrate its realm.

What intrigues Dryden more than the mere athletic talents of its playing retinue, is the genius brought to enhance the game, that is, its “virtuoso” players such as Guy Lafleur or Bobby Orr. In the chapter, “Friday,” Dryden extrapolates a concept used by Italian soccer coaches, “inventa la partita,” loosely translated to “invent the game.”[58] Inventa la partita is used by those soccer coaches more as a lament, he says, for the loss of players who can create “something unfound in coaching manuals …continuously changing the game for others to aspire to.”[59] Dryden doesn’t quite go as far as lamenting the same state of affairs in hockey as he does explicating how “a special player has spent time with his game…he has experienced the game. He understands it.”[60] It is time spent with the game, time unencumbered, time unhurried, time to assimilate and invent the game compared to “mechanical devotion to packaged, processed, coaching-manual, hockey school skills.”[61] As he states, tersely, Maurice Richard “understood the game;”[62] he invented it in his era, according to Dryden’s game-perspective vantage point. What Dryden understands in his game lament is this:

A game we once played on rivers and ponds, later on streets and driveways and in backyards, we now play in arenas, in full team uniform, with coaches and referees, or to an ever-increasing extent we don’t play at all. For once a game is organized, unorganized games seem a wasteful use of time; and once a game moves indoors, it won’t move outdoors again. Hockey has become suburbanized, and as part of our suburban middle-class culture, it has changed.[63]

As if in personal quest to understand his game, Dryden took time out in Ottawa and, “on this day, I came to the Gatineau to find what a river of ice and a solitary feeling might mean to a game.”[64] Hockey changes through external forces; the game gets re-invented by its master players, its ‘magisteri ludi.’

In addition to his historical training and academic aptitude, Dryden had an obvious perspective vantage point on the game. His trademark posture aside, as a goalie, he had an advantage unlike any other playing position on the ice – the game quite literally unfolded before his eyes. It is tempting to extrapolate goal-tender to a more stereotypically feminine or protective-nurturing role[65] as a hockey goalie, and Dryden’s “feel” for the game has already been discussed. More importantly, Dryden understood his role in relationship to the game, “A goalie is simply there, tied to a net and to a game; the game acts, the goalie reacts.”[66] It is an apt parallel to his concept of a personified game, an entity on its own, even a quasi-animate entity that actually acts. Dryden also remarks that “goaltending is a remarkably aphysical activity” that required instead a mind “emotionally disciplined.”[67] Thus, once more, it seems that the latter requirement provided Dryden with yet another beneficial factor in discerning what he learned and wrote about the game. His on-ice role did gratify him:

… to catch a puck or a ball – it was the great joy of being a goalie….There is something quite magical about a hand that can follow a ball and find it so crisply and tidily every time, something solid and wonderfully reassuring about its muscular certainty and control.

And yet even more satisfying was his relationship within and to the game:

What I enjoy most about goaltending … is the game itself; feeling myself slowly immerse in it, finding its rhythm, anticipating it, getting there before it does, challenging it, controlling a play that should control me, making it go where I want it to go, moving easily, crushingly within myself, delivering a clear, confident message to the game. And at the same time to feel my body slowly act out that feeling, pushing up taller and straighter, thrusting itself forward, clenched, flexed, at game’s end released like an untied balloon, its feelings spewing in all directions….[68]

Likewise, Dryden provides a perspicacious sense of the landscape and geography of the game. The Montreal Forum with its then two enormous, crossed hockey stick-like escalators

was his game ‘shrine’ contrasted with his description of Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens as “a period piece – elegant, colonial Toronto.”[69] The Forum and the Gardens are the two most recognized, and historically renowned architectural structures that have enshrined and showcased the game of hockey. Within these two and other arenas are the sub-landscapes. For example, Dryden provides myriad examples of locker room banter, practical jokes, pep-talks and so forth. Equally prevalent are compact, terse expressions of landscapes connected to the seams of the game: bus talk, “get the fuck outa my seat;”[70] one-sided phone conversations with wives during away games;[71] even the game’s superstitions, its tangible mysticism, “don’t change the luck;”[72] and game day, pre-game routines eloquently echoed almost as a refrain in the book, “hurry up and wait.”[73] The latter is such a vivid compression of what it must be like to be a professional athlete, mostly waiting to play their game.

was his game ‘shrine’ contrasted with his description of Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens as “a period piece – elegant, colonial Toronto.”[69] The Forum and the Gardens are the two most recognized, and historically renowned architectural structures that have enshrined and showcased the game of hockey. Within these two and other arenas are the sub-landscapes. For example, Dryden provides myriad examples of locker room banter, practical jokes, pep-talks and so forth. Equally prevalent are compact, terse expressions of landscapes connected to the seams of the game: bus talk, “get the fuck outa my seat;”[70] one-sided phone conversations with wives during away games;[71] even the game’s superstitions, its tangible mysticism, “don’t change the luck;”[72] and game day, pre-game routines eloquently echoed almost as a refrain in the book, “hurry up and wait.”[73] The latter is such a vivid compression of what it must be like to be a professional athlete, mostly waiting to play their game.

Unquestionably, one of the elements that makes Dryden’s study of the game work in such compelling fashion is his diction. His ‘hurry up and wait’ is more fluidly conveyed with:

At home, in the rhythm of the road; on the road, needing to get home. Then home again, and wives, children, friends, lawyers, agents, eating, drinking, sleeping, competing in a kaleidoscopic [an echoed word in itself throughout the book] time-sprint, for thirty-six hours, or thirty-eight or fifty-four – and we’re on the road again. It is a high-energy life lived in two- or three-hour bursts….”[74]

And akin to Hesse’s “kaleidoscope of endless metaphors,” he compresses meaning into, “a kaleidoscope of scrambles, hotels, plane rides and feelings,”[75] all themselves metaphors inextricably linked to and within the game itself. Players “assembly-line in and out of the showers”[76] and they put “sugar in salt shakers, ketchup on shoes, shaving cream on our sleeping heads”[77] all in the name of the game’s “time to act stupid together.”[78] And if we miss the point of the game’s hold on the players’ psyches and we work too hard intellectually to ferret out the logic in what they do and how they behave, the author suggests, “watch their bodies, fluent and articulate, let them explain. They know.”[79]

As much as the game breathes, has its own landscapes, and virtuoso players, it also has the characters that make up the game at any given time in the game’s evolution. Simply put, people have impact on the game, and vice versa. How do hockey trainers connect to the game? One two-word exclamation from the author suffices, “the hours!”[80] Legendary shapers of the game’s diffusion, transmission agents like Foster Hewitt, Dryden characterized as “winding up”[81] in his own end while his representation for a wizard-like crafter and game player like Orr was, “from behind he could shape the game.”[82] About a large stature player for the Canadiens, Larry Robinson who was pressured in his game, Dryden wrote about those “Bunyanesque expectations”[83] whereas another physically big player, Phil Esposito, the game’s “clown,”[84] was painted as “ebullient and mercurial.”[85] And of his own nature as goalie (as one of the “ghoulies”[86]), Dryden simply said, “I was Johnny Bower”[87] in reference to his childhood days of playing goal while growing up in Toronto when Bower was the Leafs’ heralded goalie. Thus, there is a way in which Dryden provides a clarity and distinctness in his choice of words and phrases and expressions to get inside the game as he perceived it.

What is not in The Game, compared to other sport books written by athletes is an endless list of players’ names and highlights and endorsements. The game’s players in Dryden’s time are mentioned but he is just as likely to mention and does refer to Eliza Doolittle, Bob Beamon, Margaret Trudeau, Hugh MacLennan, Roger Khan and others, not to name-drop but to provide living, non-hockey context for the game. In the same vein, Dryden provides a framework for the game in his time and place by discussing the Québec referendum (the “goddam referendum”), Montréal culture, and the French Canadian dualism (“most of my work is alingual”[88]). And yet, every piece of context is second fiddle to explicating the game itself and its pulse, “it’s life in a revolving door.”[89]

The Game is an important book, not merely for the sport of ice hockey but more importantly for its virtuoso treatment of the concept of the game. Dryden understands it, has experienced it, and has felt it. He knows and reveals that the game is metaphor and archetype and that it morphs like the transition game (offense to defense) and that it simply is be-ing with and in the game. Dryden plays in the book and he feels inside the game, caressing its timeless nuances with words and phrases and insights that bring the reader inside the game. It is a consequential book for its literary value and for its stand-alone treatment of the concept of game by an inquiring, probing, and keen mind. In sharp contrast, The Game in its 2003 edition misses the mark and regresses to the sport of hockey per se in that edition’s added chapter, “Overtime.” In that chapter, Dryden mistakenly, I believe, for the nature and perspective of the book’s original virtues, tries to bring the game up to date since he left it as a player in the late 1970s and as a writer in the early 1980s. What he achieves is a modicum of success in explaining how statistics and “machinery” have overtaken or disrupted the game and how both the Russians and Wayne Gretzky effectively changed the sport, not the game. Overtime, in effect, snuffs the life out of the game as archetype; in literary fashion, Overtime does what the blood-squeezed puck image provided at the start of this blog exemplifies about the death of hockey – it drains the game. While it is an interesting perspective, it did not and does not add to the game, it detracts from it, in my view.

In 2004, almost a year after the twentieth anniversary edition of The Game was published, Dryden was honoured by St Mary’s University in Halifax when he was conferred with an honorary doctorate degree. His comments about hockey on that occasion are more reminiscent of the game message of the 1983 text. Most certainly, they salvage the Overtime chapter’s misalignment with the 1983 game-text:

Why do we feel about it [the game] the way we do? What makes millions of Canadians sit and watch tiny flickering images scores of nights a year? What makes grown men and women buy T-shirts and sweatshirts, coffee mugs, posters and key chains of favourite teams and favourite players and talk with passion about those teams and players as if they were family? Why do certain phrases continue to buckle our knees – “my first sweater,” “Foster Hewitt,” “the year we won the championship,” “1972”? What hold does hockey have on us? It doesn’t put food on our tables or roofs over our heads. It doesn’t cure the sick, raise the downtrodden, spark our minds to do great deeds and think great things. It is just a game. We are serious, ambitious people. We have kids and jobs and bombs to worry about. There are drugs on the streets. Isn’t this attention, this preoccupation, misplaced; this money, time, and energy misspent? Don’t we have our priorities wrong? Why does hockey matter? It matters because communities matter. Kids matter. Kids and parents and grandparents matter. Friends matter. Dreams, hopes, passions; common stories, common experiences, common memories; myths and legends; common imaginations; things that tell us about how we were, how we are, how we might be – they matter. Links, bonds, connections – things in common, things to share – they matter. That is why hockey matters.[90]

And I would add, modestly, the game matters. The attraction of ice hockey to Canadians is well documented. Many Canadians remember where they were when Paul Henderson scored the winning goal in the 1972 Summit Series or when Team Canada won Olympic gold in 2002. And on the occasion of the game’s greatest player trade, poet John B. Lee recollected,

“When Gretzky went to L.A. / my whole nation trembled / like hot water in a tea cup when a train goes by.”[91]

My contention here is that what Dryden does in The Game is much like what Roch Carrier does in The Hockey Sweater[92] – they remind us both what the game is and what it means. For that reason, The Game is important culturally and historically. With apologies to Herman Hesse, Magister Ludi-dryden might well concur with Hesse’s glass bead game metaphor as succinct encapsulation of a game in play:

I read, and saw those hieroglyphic forms

Couple and part, and coalesce in swarms,

Dance for a while together, separate,

Once more in newer patterns integrate,

A kaleidoscope of endless metaphors-

And each some vaster, fresher sense explores.

Afterword

8 days after his death, tributes continue to be published about Dryden, his significance as a writer, teacher, politician, lawyer, Canadian. Perhaps the most cogent – and most in sync with my game point of view – is this Patrick Corrigan caricature published in the Toronto Star 13 September 2025:

Endnotes

[1] Ken Dryden, The Game (Mississauga, Ontario: John Wiley & Sons Canada Ltd., 2003).

[2] Ken Dryden, The Game (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1983).

[3] The Game, vii.

[4] “An Act to recognize hockey and lacrosse as the national sports of Canada,” National Sports of Canada Act, Chapter N-16.7 (1994, c. 16). See https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/n-16.7/page-1.html , accessed September 2025.

[5] Parodies of American Gothic abound; see, http://cc.ysu.edu/~satingle/AmSt%202601/parodies.htm, for example. The parody of the Clintons is entitled American Pathetic; in it, Bill Clinton’s pitchfork skewers the Declaration of Independence. I mention this – and point out the number of parodies – to underscore the impact that the original American Gothic has had on popular culture. This is no less true of Canadian Gothic; it is poignant. Other intriguing parodies portray Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Kermit and Miss Piggy, and an array of Hollywood actors.

[6] And there are an increasing number of stylizations of Canadian hockey significance widely available on the Web. They vary from Tiger Woods finishing a punishing drive, his driver replaced by a hockey stick, to a familiar side-portrait painting of Jesus Christ with hockey goalie mask pushed back over his head and captioned, “Jesus Saves, but he didn’t win the Vezina.”

[7] Bruce Kidd and John Macfarlane, The Death of Hockey (Toronto: New Press, 1972). The jacket design is by Ralph Tibbles and John Eby

[8] The Death of Hockey, p. 4.

[9] Don Morrow and Kevin B. Wamsley, Sport in Canada: A History (Don Mills: Oxford University Press, 2005), see chapter 10, Sport and the National, for a discussion of this concept of the importance of sport in the national imagination.

[10] Richard Gruneau and David Whitson, Hockey Night in Canada: Sport, Identities and Cultural Politics (Toronto: Garamond Press, 1993).

[11] Jack London, The Game (New York: Macmillan, 1905). The book is reprinted in its entirety at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1160/pg1160-images.html accessed September 2025

[12] London, The Game, p.103.

[13] There are other works on sport that use the words “the game” in the title. For example, there is the tennis book by Jack Kramer with Frank Deford, The Game: My 40 Years in Tennis (New York: G.P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1979). However, it is really about Kramer and tennis and much less about the concept of the game.

[14] Jim Bouton, Ball Four:My Life and Times Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues, edited by Leonard Shecter (New York: World Publishing Company, 1970) . More recently, Keith Gessen wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times, “In Search of the Great American Hockey Novel” (19 February 2006). While Gessen proclaimed Dryden’s 1983 book as the “last great hockey book,” that piece was more about making a plea for more hockey literature using a purposely and thinly-veiled allusion to Philip Roth’s study of baseball as American metaphor in, The Great American Novel ( New York : Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973).

[15] http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0020306652/103-2264629-6036635?v=glance&n=283155, accessed November 2005. Halberstam’s statement is part of Amazon.com’s “editorial reviews” of the book.

[16] See, for example, Dave Meggyesy, Out of Their League (New York: Simon and Schuster,1970, recently re-published by University of Nebraska Press), or Leonard Shecter, The Jocks (New York The Bobbs-merrill Company, Inc. 1969), or even Peter Gent’s novel, North Dallas Forty (New York: Morrow Publishers, 1973). Interestingly, Dryden’s book uses a very similar structure to Gent’s novel in that each chapter is one of eight days/chapters. In addition, The Great American Novel contains revelatory undertones.

[17] For example, one reviewer stated, “I have to say that this book contains a little too much introspection and not enough details about hockey and the players in it to satisfy me. I am glad that I read it and I would recommend it to fans, but I kept waiting for a little something more and it never quite came. This man has some important things to say though about life in general and for that reason alone the book is worth reading.” http://www.bostonticketexchange.com/baseball-books-plain/0470833556.html, accessed September 2005.

[18] Herman Hesse, Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game) translated from the German Das Glasperlenspiel by Richard and Clara Winston (Toronto : Bantam Books, 1970), p. 438, emphasis mine.

[19] Contemporary analysts of Magister Ludi are quick to point out how the intellectual game in the book contains uncanny parallels the Internet.

[20] Series’ memorabilia include the then ubiquitous bobble head dolls. 5 players from the ’72 series: Phil Esposito, Paul Henderson, Serge Savard, Frank Mahovlich, and Ken Dryden were replicated in the ‘dolls,’ each retailing in 2005 for US $17.20. By comparison, one could purchase some 14 bobble heads representing members of the 2002 Canadian Olympic gold medal winning hockey team (each 2002 doll retails for just over US $10.00).

[21] What might account for his lack of focus on the series is the fact that he co-authored a 1973 book on the series, see Ken Dryden with Mark Mulovy, Face-off at the Summit (Boston: Little, Brown & Company (Canada) Ltd., 1973). The book is written in diary-fashion, basically journaling Dryden’s experiences and observations from 25 June to 1 October 1972. With minor exceptions, it is a hockey book first and foremost.

[22] At Cornell, he earned All American honors, three times, for his hockey prowess.

[23] Ken Dryden and Roy MacGregor, Home Game: Hockey and Life in Canada (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Inc., 1989).

[24] Home Game, p. 10, “Hockey is, after all, people and places.”

[25] For example, it was nominated in 1990 for two Gemini awards for best documentary series and best host/interviewer.

[26] They are The Moved and the Shaken: the Story of One Man’s Life (Toronto: Penguin-Putnam, 1993) and In School: Our Kid, Our Teachers, Our Classrooms (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1995). Dryden’s business and political career were well sketched by Wikipedia Encyclopedia, “He served as Ontario’s first Youth Commissioner from 1984 to 1986. Dryden worked as a television hockey commentator at the 1980, 1984 and 1988 Winter Olympics. He served as a color commentator alongside play-by-play man Al Michaels for the American Broadcasting Company’s coverage of the famous Miracle on Ice. He became president of the Toronto Maple Leafs hockey club in 1997, remaining at that post until 2004. In the Canadian federal election of June 2004, Dryden, as a candidate of the Liberal Party of Canada, was elected to the Canadian House of Commons as the Member of Parliament for the Toronto riding of York Centre. Dryden had been selected by Prime Minister Paul Martin as a “star candidate” in what is considered a safe Liberal riding. After the election, Dryden was named to the Cabinet, despite never having held elected office before. He was re-elected in the 2006 federal election. There were rumors that Dryden eveb considered a run for the leadership of the Liberal Party. A group of supporters established a draft Dryden campaign Dryden in Wikipedia, first accessed October 2005. Dryden’s federal Cabinet post was as Minister of Social Services, a post for which cartoonists exalted in pun that he was “protecting the social safety net.” For Dryden’s goaltending prowess and continued career connections with ice hockey, see the NHL Legends of Hockey web page accessed September 2025.

[27]The London Free Press, 11 July 1979. Ting was the cartoonist.

[28]The Game, p. 261, emphasis mine.

[29] The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Houghton Mifflin, 2004, fourth edition), ‘archetype.’

[30] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955).

[31] London, The Game, p. 103; the quotation is given in full above.

[32] Some hockey enthusiasts erroneously proclaim that Canadian artist Ken Danby’s famous painting, At the Crease, used Dryden as a model.

[33] I use the term gaze in the way it is used in an aesthetic sense, a perspective with a point of view. See, Matthew H. Edney, Mapping an Empire: The Geographical Construction of British India, 1765-1843 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), p. 54 as cited in Greg Gillespie, ‘The Imperial Embrace: British Sportsmen and the Appropriation of Landscape in Nineteenth Century Canada,’ PhD dissertation (University of Western Ontario, 2001), pp. 38-39. Dryden’s pose has been the subject of much discussion, even of comparisons to hockey’s version of Auguste Rodin’s ‘The Thinker.’ In The Game’s original 1983 edition there are no pictures included in the text; in the 20th anniversary edition, there are eight pages of black and white hockey-action pictures between pages 183 and 185. In my estimation, these do nothing to enhance the game concept, rather they image Dryden during various phases of his career, underscoring his hockey experience, presumably to market the book twenty years later. Captions for these pictures are written in the third person (and I believe not by Dryden himself) including one about his leaning-on-the-stick posture, “Dryden says that leaning on his stick wasn’t a rest position, but a way to appear indifferent. After making a save, it said to players on the other team, ‘It wasn’t that hard a shot.’ If he let in a goal, to the fans it said, ‘You can’t get to me.’” (The Game, 2003, following page 183). While that might be the case, it seems to trivialize the posture to mere gamesmanship. I see it as more representative of his character and for the symbolism of his introspective perspective on the game.

[34] Christopher Hussey, Tait McKenzie: A Sculptor of Youth (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1930), p.22.

[35] The Game was simultaneously published by Times Books, a division of The New York Times Book Co., Inc., in New York, and by Macmillan of Canada, a division of Gage Publishing Limited. The dust jackets are slightly different for the two books – as described in the text of this paper. However, for all three editions to which I refer, the front cover image is the resting-on-the-stick picture.

[36] The Game, 2003 edition, p. 3. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations from the text of the book are taken from the 2003 edition.

[37] The Game, p. 3.

[38] The Game, p. 101.

[39] The Game, p. 185.

[40] The Game, p. 201.

[41] The Game, p. 206.

[42] The Game, p. 224.

[43] The Game, p. 5.

[44] The Game, p. 102.

[45] The Game, p. 130.

[46] The Game, p. 175.

[47] The Game, p. 9.

[48] The Game, pp. 139-140, emphasis mine.

[49] The Game, p. 204.

[50] The Game, p. 137.

[51] The Game, p. 50.

[52] The Game, p. 65.

[53] The Game, p. 82.

[54] The Game, p. 84.

[55] The Game, p. 91.

[56] The Game, p. 96.

[57]The Game, p. 181.

[58] The Game, p. 147.

[59] The Game, p. 147.

[60] The Game, p. 151, emphasis mine.

[61] The Game, p. 151.

[62] The Game, p. 155.

[63] The Game, p. 150.

[64] The Game, p. 149.

[65] I recall a decades-old, somewhat tongue-in-cheek article that looked at the nurturing role of the goal-tender and underscored the shape of the top of net from a bird’s eye view – it was shaped like the curves of the capital letter B, turned 90 degrees counterclockwise. The forced inference was that even the net was shaped like a woman’s bottom.

[66] The Game, p. 131.

[67] The Game, p. 133.

[68] The Game, p. 136.

[69] The Game, p. 70.

[70] The Game, p. 126.

[71] The Game, p. 123.

[72] The Game, p. 189.

[73] The Game, pages 79, 88, and 200.

[74] The Game, p. 23.

[75] The Game, p. 175.

[76] The Game, p. 70.

[77] The Game, p. 38.

[78] The Game, p. 103.

[79] The Game, p. 152.

[80] The Game, p. 44.

[81] The Game, p. 164.

[82] The Game, p. 116.

[83] The Game, p. 105.

[84] The Game, p. 113. Almost every Shakespearean play stresses the importance of a ‘clown’ or touchstone ‘fool.’ See, Don Morrow, ‘Sport as Metaphor: Shakespeare’s Use of Falconry in the Early Plays,’ Aethlon: The Journal of Sport Literature V:2 (Spring, 1988), 119-129.

[85] The Game, p. 114.

[86] The Game, p. 132.

[87] The Game, p. 63.

[88] The Game, p. 28.

[89] The Game, p. 104.

[90]The Times, St Mary’s University, Halifax, NS (May, 2004) Vol. 35, No.2, reproduced at http://www.smu.ca/thetimes/t2004-05/f3.html, accessed October 2005, brackets mine, emphasis mine.

[91] John B. Lee, ‘The Trade that shook the Hockey World’ in The Hockey Player Sonnets (Waterloo: Penumbra Press, 1991), p. 36.

[92] Roch Carrier, The Hockey Sweater (Chandail de hockey), translated by Sheila Fischman (Montreal, Tundra Books, 1984).

One Comment

RichardSmuts

Игровая платформа 1хБет начисляет каждому новому игроку стопроцентный бонус на первый депозит до 32 500 RUB (или эквивалент в другой валюте по актуальному курсу). Дополнительно, вас ожидает welcome-бонус в 1xBet казино до €1950 +150 фриспинов для использования в слотах и автоматах.

промокод 1xbet при регистрации 2025 Только с его помощью вы сможете получить бонус фрибет в размере 32500 рублей. Фрибет 1хБет 2025 предоставляет уникальную возможность игрокам получить бесплатную ставку и использовать ее без каких-либо вложений со своего счета.