dear chum

The first page of text in W.P. Kinsella’s pastoral, fantasy novel, Shoeless Joe, begins with two of the most well-chosen words relative to the theme of a novel, “My father….”

On the surface, the novel is about building a baseball diamond, in the middle of an Iowa cornfield and recapturing some of the players from the notorious Chicago Black Sox team of 1919, the year 8 members of that team were convicted of trying to fix the world series’ outcome. One of the 8 men was renowned athlete, ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson, so named after he removed his ill-fitting cleats to play in his baseball stockings early in his career. Voices in the novel tell us, “if you build it, he will come” and we are lead to believe the primary “he” is Shoeless Joe, titled on and image-silhouetted or water-marked in the book jacket above. In many respects, that foreshadowing is accurate but on another level, the “he” refers to the main character, Ray’s father. If Ray were to build the diamond, his father might come. And there is a kind of allusion in the “my father” opening two words in the novel to the Christian Lord’s prayer’s first two words, “Our Father….” Regardless, there is an incantation-like quality to the opening words of the story – magic about to happen, a story about life, about meeting one’s father much more than it is merely about baseball and some legendary fantasy. Ray’s father, Johnny, a former catcher in Class B baseball, named by the game announcer, joins the phantom Black Sox team on Ray’s baseball field and Ray, sitting in the bleachers, quite late in the story, says, “My father. My dream has been fulfilled, my request granted.” Indeed, the movie version of the story became the very popular Field of Dreams; the latter starred Kevin Costner and Susan Sarandon and is the third highest grossing baseball movie of all time. However, the movie is more romance and baseball nostalgia than thematic re the father aspect of Shoeless Joe.

In the novel, Ray has the opportunity to see his father in person and at his baseball best, long before Ray is even born. For me, having taught this novel in university sport literature classes, literally dozens of times since the mid 1980s, I have been intrigued by the whole fiction since first reading the story and always moved by those first two words. In my soaring imagination – what would it be like to know my father, to see him in his prime? Who among us can ever know another person fully and completely? I lived in the same house as my father, Lawrence (Larry) Donald Morrow for almost 2 decades and knew him into my mid-forties when he died. In an earlier, shorter blog, Spitfire, I wrote about his Air Force background and my connection to that way of life. What I write about here is what I think I know was the person my father was, a kind of literary, ruminant walk around him from my experiences, my memories, a reflection, maybe even a hymn to him, my love for him, and his impact on me. Shoeless Joe the novel is filled, over-filled some might say, with similes – comparisons that begin with ‘like’ or ‘as.’ Here, in this blog, I ask my Self, what was my father like?

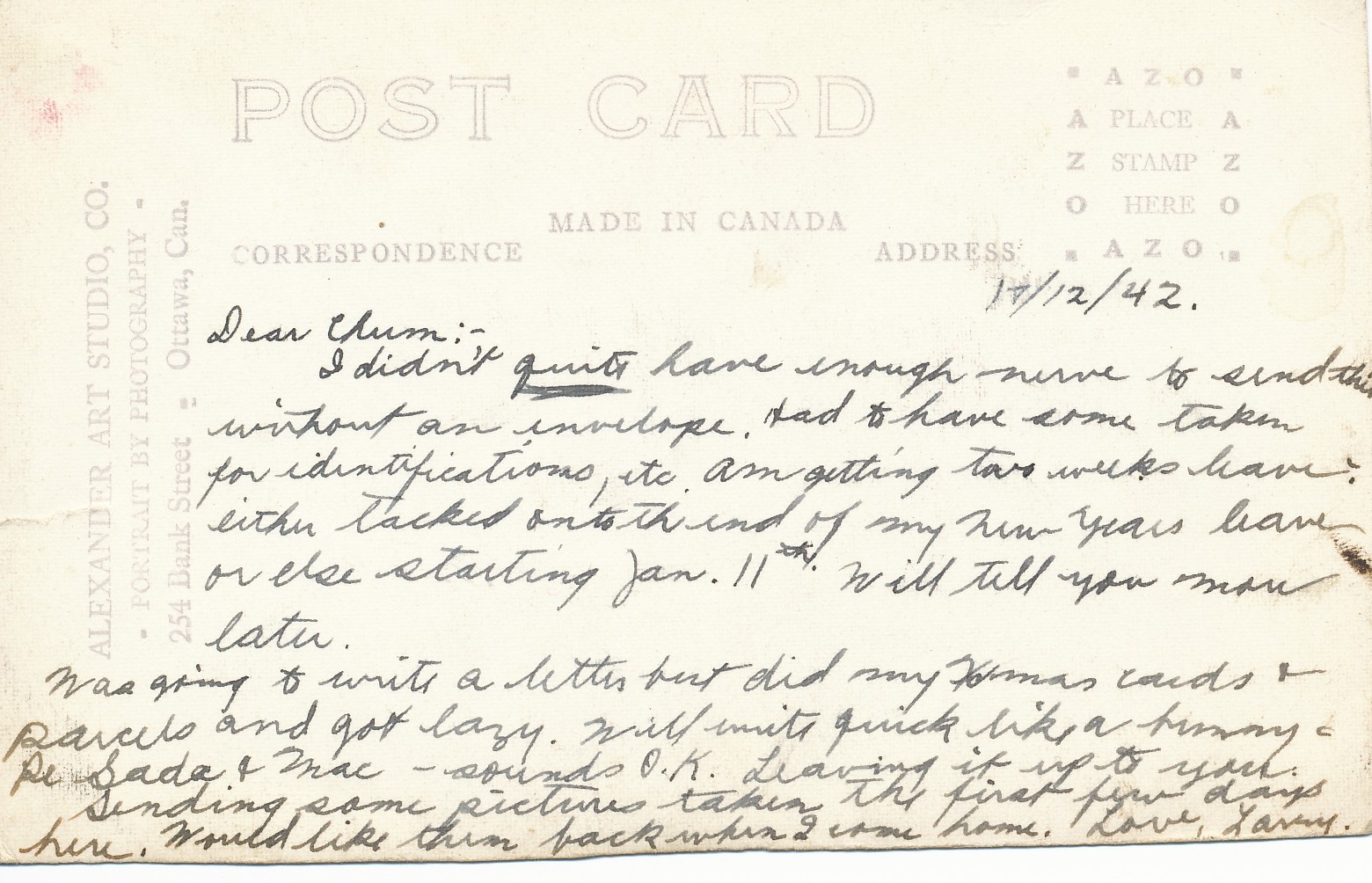

My father wrote Dear Chum in his poscard salutation to my mother on the 17th of December, 1942. Dad’s handwriting is distinctive; when I was young and working on my grandparents’ farm, he and I exchanged letters often. This card is alluring to me for lots of reasons, primarily that he called my mom, “Chum.” I don’t remember him ever calling her that in my presence and when he referred to her after her death – as infrequent as it was – in 1957, it was either Marion or your mother. Were they ‘chums’? What was their relationship like, in this case, some 18 months before they married? Was he courting her when he penned the card? When did he start calling her that? Did she call him by that name? His humility in the first sentence derives from the fact that the picture on the obverse side of the card is of him, in uniform; it seems the Air Force was preparing identification papers and he must have found out he could have a post-card made from one of the military ID pictures. Both sides of the card are displayed below:

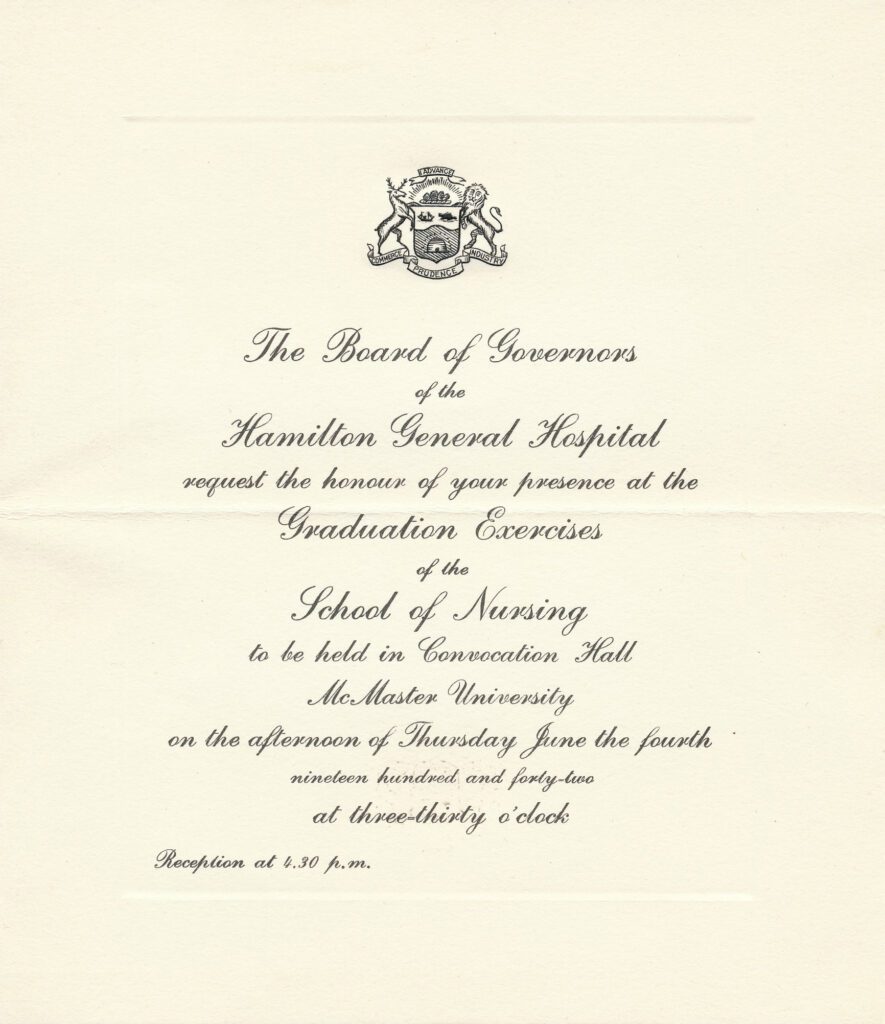

He mailed the post-card from Ottawa where he must have been doing some Air Force training related to the War. He wrote about an upcoming two weeks of leave either on New Year’s or 10 days later – where would they have met to reunite? At the time, my mother was doing her Nursing training at the Hamilton (Ontario) General Hospital affiliated with McMaster University’s School of Nursing with her graduation from that program some 6 months away. Mom’s Hamilton General Hospital and McMaster Nursing School graduation invitation is below, just because I found it only recently and it’s important to me to preserve its record:

Back to the Chum-postcard. My dad apologized for being “lazy” in not writing a letter choosing, he said, to do Christmas cards and wrapping gifts for the holiday. My father always wrote Christmas cards and was delighted to receive the same from family and friends; he would hang cards sent to him/us on strings whose ends were taped or maybe thumb-tacked to the mantle or to doorjambs in our homes. And wrapping gifts was an art-form as he did it and taught me, insisting on straight edged cuts and crisp folding and taping of the ends of the wrapping paper on every gift. In the postcard photo – he at 25 years of age – there is a serenity about his visage, his narrow, observant eyes, soft smile, and the pronounced dimple in his chin. He had been overseas by this time. What had he seen and done in the War? My father was meticulous, disciplined, and my inference from this postcard, very much in love with his chum.

Dad’s growing years and what he chose to do and how to be very much reveal what it was like to be him. One of the things he told me that always astounded me was that he grew up during the Great Depression. He said he really didn’t feel the Depression or know much about it until it was over because his family lived in such modest means. Compelling to me and connecting to the allure of Shoeless Joe described above, is one of the talents my father honed in his youth, mostly during the Depression – he was a softball pitcher, a good one from everything his brother, my uncle Roy (himself a baseball catcher until polio struck him in his mid-20s) told me.

To the best of my recollection, if we ever played catch, I don’t remember and I find it odd now that we didn’t – don’t most fathers play catch with their sons and daughters? I only shared his sport playing softball at elementary school recess, preferring to play hardball or what is more commonly referred to as just baseball. Though I fancied myself a pitcher, more commonly I played outfield on competitive teams. Dad came to watch my games on occasion, often teasing me about how far it was from home plate to first base in hardball versus softball, some 30 feet further or half the total distance from home to first in softball. The inference of his taunt, to me, was that hardball was slower and somehow then, not quite as challenging as his game. Would that I were able to ask him, seated on the bottom right in the image below, about the bright white sneakers he wore and the kind of impish or wry grin and arm-awkward pose:

My father told me anecdotes about the most famous softball pitcher of all time, Eddie Feigner, he whose electric pitch was deemed to be faster than any professional baseball player’s fastball. Feigner created the barnstorming team, the King and his Court, four players who challenged all other softball nine-player teams in some 4000 games over decades of performances. Eddie, the lynch-pin of the quartet, struck out good batters pitching not just from the mound but also from second base and at times, on his knees. Watching videos such as this one even now I marvel at Feigner’s incredible gifts. What I knew in my dad’s era, from pictures – or maybe even newsreels – of Feigner was that his delivery was round-house, a full 360 degree, windmill motion. From watching my father pitch for Air Force teams like the one he played for in Trenton, Ontario, I knew his delivery was more of a three-quarter wind-up wherein, it seemed to me, he kind of reverse cork-screwed his body into a contortion and then, unwinding, pitched starting from a momentarily paused point high above his head, not in the full circle style that Eddie used.

Struck, I assume, by dad’s belittling of my baseball compared to his softball and having seen his, to me, weird delivery style, I must have attempted to one-up him by ridiculing his pitching form. If he tried to defend himself verbally from my rhetoric, I don’t remember; what I will never forget was his demonstrative retort to my jibes. Living in London, early in my high school years, he came home from work, selling insurance, one day, years after he played his last game of baseball, carrying a brand new softball. Nonchalantly, he invited me to put on my then-prized ‘trapper’ or catcher’s baseball mitt and come out to the backyard. He told me to stand near the back wall of our house in Dundas Street and he paced off some distance he didn’t share with me. He turned and asked if I thought I could catch a ball from him if he threw it as if he were pitching. I scoffed, probably laughed and said, of course. There followed that self-coiled wind-up, the still-point at the top, then his pendulum-like release and I don’t remember even seeing the ball that smacked into my glove faster and harder and with more spin than any projectile I had ever seen. My hand burned instantly, my eyes watered from the sting. My father walked into the house, not even glancing at me, not saying a word; we never spoke about it. I got to feel my father from his baseball prime.

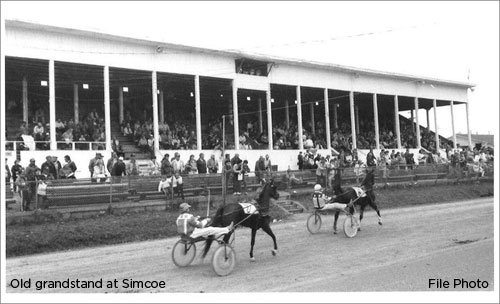

Dad’s other major sport was track, specifically the quarter mile or 440-yard race. While most tracks, until very recently were built as quarter-mile ovals, the contemporary version is the 400-metre sprint. I don’t know what my father’s performance times were in the event; however, I do know that for most of my years with him, I was acutely aware of the lithe and defined musculature of his quads and calf muscles, wrought, I assume from his years of training and racing. The tracks on which he ran were cinder and he trained, for some reason, on a primarily horse-racing dirt track, half-mile in distance, at the Norfolk County fairgrounds in the south end of Simcoe. This is the grandstand portion of the track likely from the 1940s or 1950s:

My best guess is he used the longer track to do interval and overload training and I assume his high school, Simcoe Composite School had a cinder track. Dad told me his coach had him drink several milk shakes every day, in an effort to “put meat on my bones.” I gather they thought this was a way to add weight using the then unquestioned wholesomeness of milk and whatever else went into the beverages.

My father must have had a genetic predisposition to more dominant fast-twitch muscle fibers in his legs; that is, the major muscle groups used in his 440 event contained a significant proportion of those rapid-fire fibers enabling him to generate significant speed and power. The 440 is regarded as a very tactical race in that the sprinter has to run right at the edge of their maximum speed over the quarter mile, being careful not to run at a 100-metre pace thereby depleting muscle energy too quickly to sustain performance. As for me, I seem to have inherited exactly none of my dad’s sprint-talents or his muscle fibre composition; in fact, I have a preponderance of slow-twitch muscle fibres. From lab testing, I also know I did inherit a very high maximum oxygen uptake meaning that I have an ability to sustain aerobic sporting events, like running, over long periods of time – I have a high endurance capacity. Where my father sprinted, try as I might have in school to be a fast short-distance runner, I just did not have that ability. I could perform well in racket sports but I attribute that to hand-eye body coordination and agility, not to any movement velocity capabilities.

So, I wonder what it was like to move as fast as my father. What did he feel like during the quarter mile, to run across his own speed and measure himself against others? Did he enjoy training? Did he revel in how his body felt when he ran? Did he own spikes? What did he regard as his racing triumphs and his disasters and did he treat those imposters – triumph and disaster – the same? When I knew him in my childhood, I knew he loved to move fast when he walked; as a young boy, I always felt like he was pulling me when we walked together. He held me by one wrist and always seemed to be dragging me. After his heart attack in his early 40s, medically he was advised to walk for exercise and often when I saw him on his walks, it looked like he was race-walking in almost a military marching motion.

When I took up marathon training and running in my late 20s, he taunted me in a fashion reminiscent of his baseball running to first base goading. He wanted to know what was the point of running at the same speed for hours instead of running as fast as possible. He tried to understand what someone blessed with slow-twitch muscle fibers was doing measuring his speed over miles of terrain. Once, he asked me if I ever drank “those sport beverages, like Gatorade.” Disgruntled at even the thought of doing so, I said no, just water and that to me, during a run, sport drinks tasted like horse piss. Pausing and in his subtle but inimitable fashion, he said, “Oh, interesting…how would you know that taste?” It never occurred to me to ask him why he ran the 440 and not the much shorter 110-yard race. Wouldn’t he have done the same kind of thing as me, relatively speaking, in pacing or controlling his speed over a distance 4 times as long as the classic, premier sprint event? My father and I shared a passion for running; we each felt what it was like to move our bodies as fast as we could even if in very different ways.

I know very little about my father’s years as a child; he showed us the house he lived in as a boy, on Highway 3 just outside of Simcoe; that may have been the Dawson (my paternal grandmother’s name of origin) family farm where dad was raised. The earliest picture I have of him is the one on the right above, with him seated in front of his older brother Roy and his mother, Mary (Myrtle Dawson); perhaps he is 4 or 5 – the solemnity in their faces is striking. On the left is my mom, Marion, and my father – best guess would be sometime in the early to mid-1940s. Mom looks elegant to me, poised, the space between her front teeth is something I do remember and share to an extent. Very likely this is a studio portrait; my mother’s lips clearly lipsticked and carefully coiffed hair. I have many photos of my father as an adult and in this one, more than any other, I see and sense his happiness, the light in his eyes, the curls in his hair, the contentment in his face; his beloved chum, radiant, beside him, he wearing his earned air force pilot wings, and the pronounced dimple in his chin – nicked often while shaving with his Gillette razor – a feature I always noticed about his face. Did my mother admire his dimple? She must have done so. I feel my father as a man, in his prime, reflected in that photograph. In the photo beside, I see the boy that became the man, little Lawrence’s hands – strikingly foreshadowing the same hand-arm positions in the softball picture above – and feet uniquely posed, with soft eyes and lightly pursed lips. I have to think that their names penned on the photo, Roy, Mary Morrow (one last name misspelled and scratched out), and Lawrence, the latter barely discernible at the bottom, were in my grandmother’s hand-writing.

I often wonder what my dad’s relationship with my mother was like. As I have noted elsewhere I remember virtually nothing about mom. As I know now, her nursing training resulted in making sure her children had regular bowel movements – milk of magnesia was a daily staple, enemas frequently. Mercurochrome and iodine were in abundance in our medicine cabinets, both essentials for antiseptic use. I remember her tinkling her drinking glass with her fingernails, perhaps a nervous habit. Both she and my father spanked me – Dr Spock reigned supreme – with a wooden spoon or my dad’s belt. When we lived in Centralia, for some reason I use to get boils on my bottom and I vaguely remember Mom using a warmed bottle top and probably a needle to break and drain the pus. Dad made liver and onions as a favoured meal and I remember mom loved Velveeta cheese, a processed cheese spread that came in large rectangular packages. Did she cook our meals? Did she ever get to practice nursing, marrying in 1943 (on June 26th) and having their first child, Sandra Carol, just over a year later? There was an angst about her and perhaps I make that up in my mind and my vague memories of her. My dad told me several times that mom and I had a special relationship, a strong connection, he said, and if so, I have no sense of that bond. I do recall many instances of her anger at me – I used to pull out my eyelashes, not sure why, and she got very cross at me. I remain perplexed about why I remember those things and not more of who she was, what she valued, and how she behaved, especially in her relationship to my father, her chum. Stored in our basement rafters in one of our rented homes, I recollect seeing 2 sets of very wide, wooden Alpine skis. Where would they have skied? The sport was never mentioned to me by my dad. Once, very late in his life, dad shared that mom asked him to teach her how to shoot a hunting rifle. He obliged and taught her on his mom’s farm. He said she held the gun awkwardly, sighting down the barrel at a lightning rod on a barn, my father certain she would never hit it. She did and when he told me this story, he said “kapow” to mimic the rifle retort, clapped his hands hard (to indicate the shattered bulb sound) at the same time, and laughed heartily recalling the lesson in his mind’s eye and her first-time skill.

My father did at least some of his service and pilot training in Dunnville, Ontario. My research tells me he also would have learned advanced techniques like formation flying, low flying, bombing and gunnery, night flying, instrument flying, radio work, and become familiar with the administration and procedures associated with operating and maintaining military aircraft – mostly Harvard and Anson planes. Shortly after graduating in 1941, if an account in the Simcoe Reformer newspaper is accurate, dad met Queen Elizabeth, wife of King George VI. The press clipping reports that he spent 5 minutes chatting with her while on leave and visiting at an armed service’s club in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was Sept 22nd and in a letter to his mother, dad said she was dressed in pale blue and that the King followed her, not speaking. My father and the Queen discussed the popularity of Scotland for Canadians and, “she discussed our work a bit, being very careful not to ask any questions that we shouldn’t answer.” Interestingly, he related to his mom that he wasn’t “the least bit nervous – the Queen makes you feel perfectly natural.”

He was a very private man and yet one who very much enjoyed socializing, an introvert with extroverted qualities, the latter serving him well in sales’ fields like those he chose in retail clothing and insurance. Even if she had asked, my father would have said nothing to the Queen about his war training or work. As an insurance agent later in his life, there were many times when he cautioned me never to reveal the names of his clients, personal or commercial and certainly never disclose our family’s financial situation. I learned respect from my father, respect for people and their privacy, regardless of their station in life.

There was, in my view, an enigmatic quality to my father. As kind and affable as he was, like everyone, he had his darker side. Never able to empathize with my fear of heights, for example, he would rock vigorously a shared ferris-wheel seat when at its apex of the ride, laughing as I screamed and begged him to stop. Knees quaking, on another occasion, I stood high up an extension ladder picking cherries and dad took great delight in shaking the bottom of the ladder incredulous that I was in abject fear. Aside from spankings, I recall once he was furious at me for teasing my younger sister and twisted my arm up behind my back while he scolded me. To him, police officers on motorcycles were “boogie men on two-wheeled kiddy-cars.” When at the end of grade 11, I bought my first motorcycle, a Yamaha 80 belt-drive, he reminded me often of his derisive kiddy-car phrase. If he were angry at some international political faction, his solution was a pronounced “shoot the bastards.”

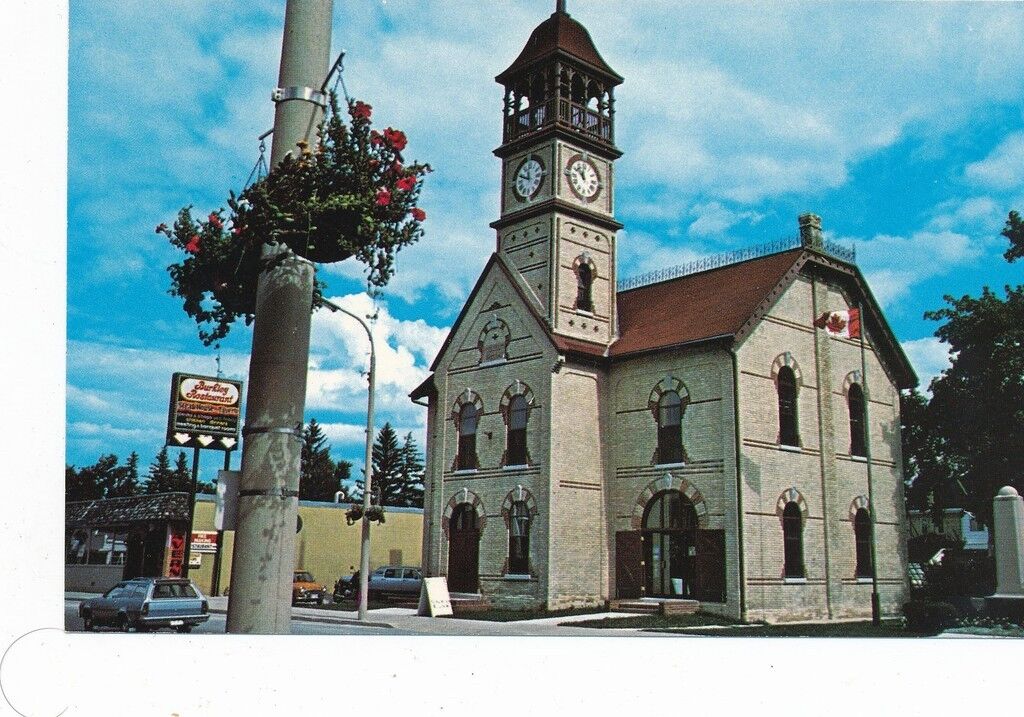

He could not or would not talk about his war experiences or my mother. Oddly, he owned a German luger pistol and he had a short, sheathed sword with a bone handle; at its hilt was an embossed swastika – what the story was behind those two items, I will never know. Talking about mom in anything but a passing reference he said was just too difficult. Children had to have jobs when they were young. And so, starting in grade 6, I delivered newspapers, first the Star Weekly and then the daily Toronto Globe and Mail. From my Star job, I saved up to buy a beautiful set of binoculars; when they came in the mail, in a strapped leather case, to our home in Simcoe Street, Exeter, I promptly took them up to the top of a windmill located in the farmer’s (Louis Day was his name) field behind our home. Curiously, it was not a height issue and I suspect my motivation was to get a better view. Seconds after I pulled them out, I dropped them into the murky, spider-surrounded and deep well beneath the windmill. My father was furious at me for losing them. For the Globe delivery, in grades 7 and 8, I had to get up and be at the Exeter town hall by 6:00 am, most times, it seemed, waiting for the truck delivery of my paper batch and then peddling them in distribution around the town, then doing cash subscription collections every Saturday. My dad seemed confident this was great training for life, perhaps it was. This was the Exeter town hall circa 1960s with my beloved Berkeley Restaurant situated next door, a venue where I spent my paper route money to drink many a cherry coke and eat French fries:

At the same time, my dad had so many idiosyncracies and qualities and behaviours that drew me to him in admiration, sometimes awe, and love. He found the televised Mr Magoo, a fictional, myopic, millionaire cartoon character and his family antics just hilarious; ‘oh Magoo…you’ve done it again,’ dad would echo. We shared a remarkable connection in watching Danish comedian/pianist Victor Borge do his phonetic punctuation routines; the first essay I ever did in elementary school was on Mr Borge. An inveterate reader, dad read all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason series of detective stories and was disconsolate when he finished the last Louis L’Amour western novel. If anyone burped, he retorted, “Oh!…if that comes up again, we’ll vote on it.” Among his many expressions, his most frequent one was “whoop tilt,” for something unexpected that happened and the quirkiest to me was “heavens to murgatroyd,” applied as a mild exclamation to seemingly anything. Every Saturday, he did our family laundry on a wringer washing machine, drying everything by hanging our garments (my ‘chore’ often) on outdoor clotheslines. His refrain for laundering out bedding was ‘bottom sheet goes in the wash, top sheet goes on the bottom, get a clean top sheet.’ The inside of our homes had to be kept clean – what if company dropped by? And to me, company never dropped by. Dinner always had to be at 5:30 pm, just the way it needed to be, the Air Force in the man. Sundays were ‘get-your-own’ dinner, each of us, my two sisters, my dad, and I made our own individual dinners – French fries cooked in oil in our deep-fryer was my staple.

At the same time, my dad had so many idiosyncracies and qualities and behaviours that drew me to him in admiration, sometimes awe, and love. He found the televised Mr Magoo, a fictional, myopic, millionaire cartoon character and his family antics just hilarious; ‘oh Magoo…you’ve done it again,’ dad would echo. We shared a remarkable connection in watching Danish comedian/pianist Victor Borge do his phonetic punctuation routines; the first essay I ever did in elementary school was on Mr Borge. An inveterate reader, dad read all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason series of detective stories and was disconsolate when he finished the last Louis L’Amour western novel. If anyone burped, he retorted, “Oh!…if that comes up again, we’ll vote on it.” Among his many expressions, his most frequent one was “whoop tilt,” for something unexpected that happened and the quirkiest to me was “heavens to murgatroyd,” applied as a mild exclamation to seemingly anything. Every Saturday, he did our family laundry on a wringer washing machine, drying everything by hanging our garments (my ‘chore’ often) on outdoor clotheslines. His refrain for laundering out bedding was ‘bottom sheet goes in the wash, top sheet goes on the bottom, get a clean top sheet.’ The inside of our homes had to be kept clean – what if company dropped by? And to me, company never dropped by. Dinner always had to be at 5:30 pm, just the way it needed to be, the Air Force in the man. Sundays were ‘get-your-own’ dinner, each of us, my two sisters, my dad, and I made our own individual dinners – French fries cooked in oil in our deep-fryer was my staple.

When he did some of the house cleaning, he always included a sit-down at the piano and played, with two hands, something he called “chicken tracks.” It was the only piece he ever played. He loved listening to singer Teresa Brewer and Good Night Irene seemed to be his favourite song along with K-K-K Katy, the popular World War One era song about a stuttering, awkward soldier lovesick over “beautiful Katy.” My dad appeared to be just thrilled doing the stammering, hard consonant sounds from that song’s lyrics. He was a good singer himself, a choir member, a tenor, I believe, when he was growing up. He flooded rinks in our backyard, himself never having even tried to skate. Adept at running, flying, and baseball, he just could not swim – he did the sidestroke with great effort, seeming to drag his torso that sank like a proverbial stone. In contrast, he did tell me my mother could “swim like a fish,” and I have a vague recollection of her with us swimming at Port Franks, a Lake Huron beach. During the 1950s, when dad did prospective pilot-trainings out West or East, he always brought his children presents from wherever he had been (see my Spitfire blog re his pilot exploits).

Dad devoured and spouted Dale Carnegie’s writings, especially his How to Win Friends and Influence People. To this day, I believe my father was a master at teaching. Clearly, he was adept at training pilots but it was in day-to-day things that he just seemed to have a way of conveying how to do or how to learn something. He taught me how to drive a car – our 1954 Meteor that he had painted black because I wanted a black car (we still had it in 1967 when I acquired my license) – either before commercial driving schools or just because he could do it; every time I parallel park, rarely having to do any adjusting, I remember the vector cues he taught me. He was a bit of a wizard at doing mathematics and he passed that on to me through his examples of geometry and algebra. Physics, like Bernoulli’s principle and centrifugal force I learned from him before I was 12 years old. My father was smart in school, narrowly missing a university scholarship when he graduated high school; not getting the funding meant he could not afford further education, a learning experience I think he would have loved.

An adept bridge player, he often tried to lure me from euchre and hearts to his game; I resisted until my university days. For me, his lessons about little things, like unplugging a toaster before trying to pry bread out of it with a utensil, or carrying sharp implements with care, or tending strawberries in our gardens, were and remain embedded in my memory. He explained parachuting technique to me as a boy; he said it was like jumping off a 17-foot structure re the impact and as soon as you landed, you “just” turned both knees to one side and rolled onto your side. Naturally, I longed to try it and for a jump-off point, I selected the bandstand roof – I adjudged it as 17 feet – at a park in Kincardine, my mother’s hometown. The resultant sprain was severe and I suspect my father felt his parachute pedagogy had, at best, an unintended consequence.

My father had a pious quality about him that was revealed patently when he went to church. We were Protestant, United church goers – although my mother grew up in the Presbyterian church, her father an ordained minister (Reverend Thomas Davidson McCullough who died in 1938 when my mom would have been in her late teens) – and in high school whenever we went and we almost always went, he would sit down in the pew, edge forward on the seat and rest his forehead on his upturned fists, praying with a physical reverence, I assumed. Devoted to his children, the vagaries of life had not been kind to him; both women he loved – my mother and a woman he dated many years later – died of very similar health issues and for some reason, his ritualized church prayer seemed to me to be his acquiescence to things he could not understand or control.

My dad smoked cigarettes – du Maurier was his brand – and loved the habit; it was a way of being both with himself and with others; he would sit in his favourite chair for hours tapping his cigarette ashes in a huge, upright, black-bowled ash-tray, notched to rest his cigarettes. Convinced I could somehow impact his habit, I once asked him, “dad, don’t you know if you quit smoking you’d live longerr?” Immediately and definitively he replied, “No, it would only seem longer.” And I got it, even though I disagreed with and did not ever share his habit, he loved everything about smoking. He took up golf later in his life, probably in the mid 1960s, a few years after his major coronary. The walking suited him and he could figure out the game, swing changes, hitting percentage shots, watching Palmer and Nicklaus, and playing with friends. As an insurance salesman, he didn’t start his work-day until late morning so he played 9 holes early most mornings. When high school was out for the summer, before I went to work in tobacco harvests each year, he convinced me to go with him. I loathed the game, still do, but I went with my father and tried to listen to his golf tips and stroke corrections. He had a way of being annoyingly direct in his golf stroke feedback to me. For example, when I shanked a ball or missed my target widely, he would point out, in what seemed a cavalier fashion, “well Son, the ball went right where you were aiming with your stance.” Probably true, but devoid of empathy for how ticked off I was at myself. I think now I was just too competitive in that he always out-scored me and was far more deft with his clubs than I ever was. Sadly, he was forced to give up golf when in the early 1980s, he had to have his left leg amputated just below the knee, due to the ravages of smoking on his circulatory system – the venous return vessels had shut down in his toes. I often think about his immediate post-op hospital bed recovery; he was in such pain and I held his hand and remember him saying, “you must think your old man’s a suck.” I had no such thought but I wept for his agony and his loss of limb. With his prosthesis, he tried modified golf swings but it just wasn’t the same and I remember him declaring to me that he was giving up golf because of “this cussed leg thing.”

My father was father, husband, grandfather, son, athlete, teacher, flyer, and so much more. He was affable, witty, family-devoted, smart intellectually and practically, disciplined, and lovingly touched and hit hard by life. Mostly, my father was pilot, literally and figuratively. What was my father like? Writing from my memories, I feel the fullness of Kinsella’s simile in Shoeless Joe in that this particular blog-writing process – revealing and reveling in my father’s life – has been akin to watching a cloud “uncover[ed] the moon, like a magician peeling his silk handkerchief off an orange.” Just as Ray remarks in the novel, the “cosmic tumblers” of the universe were such that Ray was able to create the ball-field and see his father in his prime, so too do I appreciate the privilege of being able to tumble home to my father choosing to remember him and feel him figuratively as he must have felt, for example, stepping excitedly, proudly, and confidently into or out of the cockpit of an airplane, parachute attached…

Judging from his face and shorter hair, slightly overweight perhaps, I’d guess this picture was from the late 1950s, maybe in Centralia.