Singing auditoriums

My high school, Sir Adam Beck Collegiate Institute in London, Ontario, was very special to me and to a host of students over many years. My family moved to the city from Exeter, after my father’s heart attack and retirement from the Air Force, just as I was entering grade 9. I remember he offered us, my 2 sisters and me, the choice of staying in Exeter or moving to the big city in order for him to join an independent, general insurance company. We chose the city. My delight in previous trips to London was going through the village of Arva on the sign for which someone had hand-painted a big ‘L’ before arva and I found that hilarious. We rented a home in east London, at 1305 Dundas Street right near its intersection with Highbury Avenue. The house is gone now, replaced by a post office; it was located on the south side of the street right across from Beck Public School and its adjacent Collegiate high school separated by a large tract of land in the centre of which were 3 fenced-in asphalt-based tennis courts.

Our home was huge with 4 bedrooms and a bathroom upstairs; another bedroom my dad occupied on the main floor and a small bathroom, a front room we called the drawing room because you could draw a large glass-panelled, pocket-door to enclose the room; full living room; small kitchen and then a rectangular, closed-in porch, encased by windows on the east and south sides, that we used year-round as our main eating area. One of my favourite memories is sitting in that room on very cold, stormy winter days watching cars coming down the Highbury hill, often way too fast for the road conditions, and getting into fender-bender, bumper-car-like accidents as they tried in vain to stop at the traffic light. For some reason, it just tickled my funny-bone, sort of like watching my own Keystone Cops movie reel but in real life. And, I retreated to that porch daily, as the point farthest from our drawing room wherein both my sisters practiced seemingly endless piano scales and skills on a very large, grey upright piano. For years, that instrument was tuned by a man who was blind, his sense of hearing, I assumed, heightened by his loss of sight – he too was fascinating to watch.

For me, living in that house meant that for most of my 5 years – high school went from grade 9 to 13 at the time – I was steps away from Beck, my nirvana. At the end of grade 11, we moved to 730 Sevilla Park Place (Adelaide and Huron area) and that meant using the London transit bus system in cold weather and my Yamaha 80 motorcycle in warmer weather – the new distance from Beck did nothing to dampen my allure to my high school. Beck was my place of complete peace and happiness. And my first day of grade 9 was memorable and did not forecast the upcoming contentment and joy I would encounter over those years. Shy and small, I was assigned a home room for 9A; when I found the room itself, I was the last student to get there because there was only one seat left. And that one-armed bandit-chair was in the middle of the second row from the far side of the room and right behind the most beautiful girl I had ever seen in my life! I was smitten and so nervous I couldn’t even speak, don’t even remember sitting down. Long auburn hair streamed down her back over her diaphanous white blouse and she seemed absorbed in reading a magazine she held up in front of her. Some students were talking but I did not know a soul. In the minutes leading up to the teacher’s arrival, I just sat transfixed and silent. My fear, that she would speak to me; my heartfelt desire, that she would speak to me. And she did and her words became indelibly imprinted on my psyche for decades. She turned her torso slightly to her right and backward partially to face me, pointed to an advertisement I never saw and said, deliberately, interrogatively but with very little intonation, “how would you like to drink a tall, cool glass of pus?” And she turned back to her magazine. Perhaps, from my now Jungian perspective, this was my first glaring encounter with the shadow side of the feminine. Below is my grade 9 picture; imagine the colours – yellow sweater with black accent-piping, my “bumblebee” sweater, as I called it then:

Despite my first day at Beck, what unfolded for me were vast opportunities. Without question, school for me was always magnetic in its allure of repeated and varied challenges; achievements consistently beckoned. In elementary schools, math quizzes, spelling bees, exams…anything that required my full attention were absolutely thrilling to me (I still watch spelling bee competitions on television). Getting badges in Cubs and Scouts (right up to obtaining Queen’s Scout status), or being awarded annual Robert Raikes’ medals for Sunday School attendance at various United churches were all part of my unrelenting quests for accomplishments. Beck was like a private school disguised within the public school board. Teachers were outstanding in their instructional capabilities, their expectations, and consistent commitment to students. One of my favourites was Dennis Groat, my Latin teacher. Impeccably attired in starched white, long-sleeve shirt and tie, Mr Groat delivered Latin to his charges armed with a wooden pointer which he utilized semi-emphatically to explain sentence parsing, verb conjugations, and even geographical areas of the ancient world. Learning a ‘dead’ language seemed no different to me than any other subject and it offered the same draw as any other branch of knowledge…learn, even memorize, excel on tests. To this day, I still claim Latin was fundamental, foundational, and important in getting a command of the English language, figuring out root-words, learning new languages, and understanding the derivation of anatomical structures and functions. And, I even skipped tennis games at lunch period to take optional Greek classes with Mr Groat.

There were many more teachers who impacted me as a person as well as my thirst for learning. Thelma Pittendreigh comes to mind as perhaps the most curiously named teacher I encountered; Mr Bartley, French teacher nonpareil from whose rendering of Albert Camus’ novel, L’Étranger (The Stranger), I came to appreciate French literature right through several university courses; Miss Waite to whom I am still grateful for taking an interest in my academic coasting in grade 11 and having the courage to call me on it in a way that drew me out and did not shame me. Most of all, I remember three male teachers – Bill Dunlop, Jake Barclay, and Michael Sharratt, all Physical Education teachers at Beck. Sport, I see now, was my mistress. Growing up on small air force bases in small towns, I knew but two season in life – baseball was summer, hockey was winter, the sequential, reverberating phases of my boyhood days. I had never seen a tennis court or basketball nets or a trampoline til arriving at Beck in the Fall of 1962.

Athletic by nature and experience, I spent every secondary school minute I could revelling in any sport or physical activity available to me – in the vernacular of that era, I was a gym rat. In seasonable weather, the long, looping driveway going into the school was superb for skate-boarding; and the asphalt parking area outside, the west-facing brick wall was a perfect rebound target for practising tennis strokes on my own. And those three PE teachers not only inspired me in classes but they organized both interscholastic sports – we were the Beck Spartans of green and white colours – and intramural sports, the latter with programs and activities that fostered both interest and widespread participation. From floor hockey and basketball to paddle-ball to badminton and tennis, any sport seemed my domain, and tournaments and competitions in all those activities abounded. Converse All-Star running shoes were coveted and special to me from what I knew of pro sport. At the same time, when first handed my own gym apparel in grade 9, I had no idea what the jock-strap contained within the apparel role was used for, let alone how to put it on.

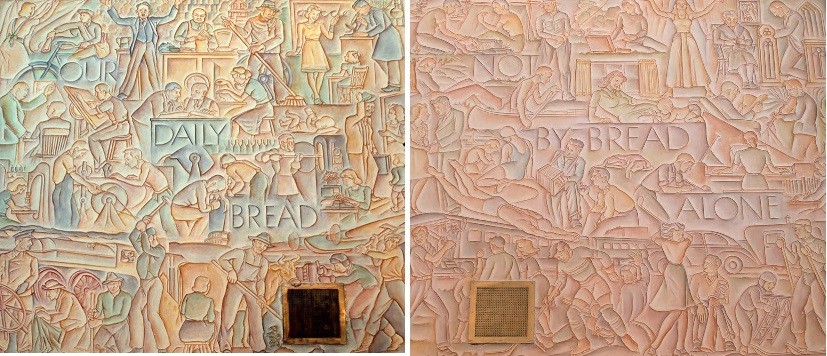

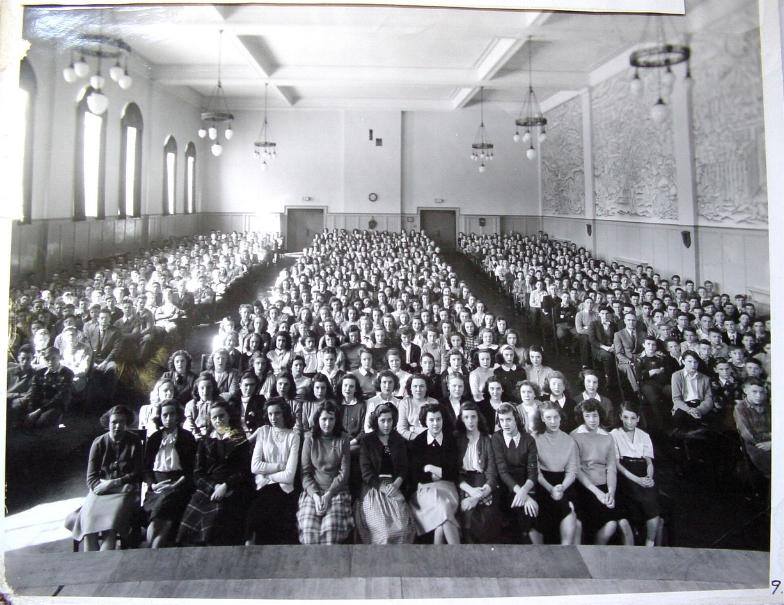

What made Beck so unique from what I came to learn then and over the years since my high school days, was its fostering of all dimensions in students. Athletics, despite the plethora of trophies in the front foyer, were no more important than music or drama or academic classes; the gestalt of Beck was that the whole school was very much more than the sum of its parts. Clubs abounded and I was a proud member of the Key Club, a kind of junior-Kiwanis service club for which we voluntarily cleaned up yards for those who couldn’t or attended different denominations of churches just to learn alternative perspectives on religion. In grades 12 and 13, I volunteered to be a prefect; wearing a green and white arm-band signified that I and my fellow prefects were authorized to patrol the hallways and look for misbehaving students; I don’t remember what we were able to do if we found any miscreants. Curiously, what united us all were singing auditoriums. The picture at the top of this blog is a depiction of Beck’s auditorium, a large, theatre-like room with fixed seating. The huge mural covering one length and width of the room was created by a former art teacher, Selwyn Dewdney (brief bio here) who taught at Beck from 1936 to 1945 when he resigned in protest at the demotion of a colleague. Apparently, some of Selwyn’s art students were involved in in the construction or mounting of some parts of the mural. At the front of the auditorium, the stage was sort of symbolically buttressed on either side by these two large panels:

The captions read, Our Daily Bread and Not by Bread Alone

They were curious, clustered representations of people and events from industry, agriculture, education, sports, and science, the characters some say were representations of Beck teachers in Dewdney’s time. At any rate, the images just seemed to envelop us in the auditorium. The stage was used for speech competitions, drama productions, award presentations, and even trampoline practice for me. However, every two weeks – if memory serves – on Fridays, periods were condensed, and in two, back-to-back assemblies (to accommodate all students), we came to the auditorium and sat in rows designated by singing voice – soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. On stage, the music teacher – even the principal, at one time, Carl Chapman, and a vision-impaired and beloved PE teacher, Will Rice, the latter always wearing sun glasses – Gerald Fagan during my tenure at Beck. They conducted us using a baton (I think) or very demonstrative arm movements, a piano, and a huge screen with an overhead projector to display songs like Autumn Leaves, No Man is an Island, You’ll Never Walk Alone, Alouette, 500 Miles, Christmas carols in season. And we all sang enraptured by the experience, lights dimmed…it was elegantly the timbre, resonance, and culture of the school.

Music, I confess openly was, euphemistically, not my forte. To be clear, I don’t hear a beat in music, carrying a tune nearly impossible, and my (tenor?) singing voice is only honed in the shower and when driving alone in a car. Perhaps my distaste for learning music stems from my Aunt Jean, at onetime a Supervisor of music for the London Board of Education, who chased me up the stairs of my Trenton home in mid elementary school years, saxophone menacingly clutched in her hand, literally demanding that I learn to play it while I refused in body and soul. In the same vein, in grade 9, one of my required subjects was Music Appreciation, a course taught by Mr Fagan – he of Singing Auditorium prowess mentioned above – who, at the time, was just beginning his teaching career. We knew him as Fingers Fagan because it was rumoured he wore gloves to play basketball in order to protect his hands for piano-playing. True or not, I liked the myth, one reinforced by another of his idiosyncrasies when in grade 10 English, his other academic area, leaning back in his chair feet up on his desk, he asked the class once if our teeth ever itched, as his did, presumably. His music class took place in the band practice room and I always sat at the back, disinterested in the topic completely and probably not subtle about my attitude. Part way into the course, as Mr Fagan was explaining some musical nuance, I was biding time in class, picked up some kind of wire brush and gently tapped what I now know was a ride cymbal. It made more noise than I expected and the next thing I knew, a white piece of chalk zipped past my ear and struck the wall behind me. I don’t remember what he said to me, but he had my attention for the remainder of the course.

And yet, despite my apparent resistance to music, these singing auditoriums were precious to me. In German class, in my last years of high school, “Friar Tuck,” as we called our language teacher (his last name was Tuck), had us sing O Tannenbaum (O Christmas Tree), in full-throated German and it seemed normal. I prepared for exams, memorizing poems, going over geometry formulas, sitting in an empty bath-tub at our home on Dundas Street all the while listening to rock music as I studied. We didn’t speak about singing or auditoriums, didn’t realize how unique they were; they were Beck. What I did glean musically after 5 years experiencing these semi-monthly gatherings was the vibration of music that appeals to me. Music that I appreciate actually vibrates, tuning-fork-like on my sternum; I just know what sounds good to me – Moon River, Bohemian Rhapsody, Unchained Melody, anything by Simon and Garfunkel, all reverberate on that chest bone. Lyrics fail me, refrains I remember sometimes but it is the sound under the music I hear; most of my doctoral dissertation was written listening through big, black, cushioned ear-phones to album after album of Nana Mouskouri’s songs. In the 1970s and 1980s, I watched my older sister, a high school vocal music teacher, conduct her choirs, oblivious to her skill but entranced by the sounds she and her choirs produced (like my favourite, the spirited Jump Down, Turn Around, Pick a Bale of Cotton or Goodnight Irene, in tribute to my dad’s favourite song). And when Mr Ford, Beck’s band leader/teacher stood on our auditorium stage and played Wonderland by Night on his trumpet, unaccompanied, the range and exquisiteness of the sounds and my admiration of his talent held me spellbound. I tumble home often to my years at Beck, semi-lured by calls for reunions that include recreating those singing auditoriums; I prefer to leave them tumbling in my memories.