Berries, Pins, & Copper Tees

As Summer 2022 blends delicately into Fall, I have been thinking back to all the jobs I had during my high school and university years. Most students experience the agony and the ecstasy of working at summer jobs. In reflection, I thought of those jobs as kind of in-between real life time with a view toward making as much money as possible to have during my secondary school academic years and to help pay tuition and attendant costs while doing university degree programs. Some of the summer jobs extended into the academic year; however, playing sports limited the amount of time I could commit to working during school time. I learned a lot doing those jobs, met some amazing people, and tried to approach those enterprises as I did and still do as tasks to be done well – kind of challenges borne of necessity and yet ones in which I could immerse myself. Thus, I choose to reminisce about my Summer jobs many decades having past since I did any of them. What do I remember about those jobs? What did I learn doing them? What remnants linger in my imagination about those salad days and months of hard work and yet so much joy of effort.

My very first job, outside of household chores as a boy, was delivering papers on a paper route in Exeter, Ontario. Those experiences have been described in my Riding History blog. Sometime during late elementary school, my Uncle Roy (my dad’s brother) and my dad decided their sons, me and Richard should pick strawberries. In passing, I want to acknowledge my Uncle Roy for all the life-lessons I learned from him. Stricken by polio in his twenties and relegated to walking with canes and all manner of braces and corsets for the rest of his life, his resilience and passion for life were just stunning. And having lived with the torment of hip osteoarthritis, minor by comparison, I cannot imagine the pain he endured daily. As a boy, my uncle seemed fierce, even mean. He had a deep voice and a scowl that, in tandem petrified me. He would chastise us as children for the smallest – it seemed to me – of misdemeanours such as not getting to sleep quietly or spilling a glass of milk. Often, he would raise his arm and hand in a preparatory slap-gesture, never actually hitting us. As I see him now, I truly believe he used every opportunity to teach us important lessons about life. Many, many times he said to Richard and me, “if a job is not worth doing well, it’s not worth doing at all.” I have never forgotten that aphorism and it became a belief and I think a practice of mine throughout my life. All of my uncle’s cars – do I remember correctly his yellow 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air – were custom-fitted with a hand-brake near the steering wheel due to the fact that Roy could not lift either leg without using one hand under his rear thigh.

My father held his brother in inestimable esteem; they were good friends and my family and I spent a lot of time in Simcoe with Roy, my Aunt Betty – one of the kindest human beings I ever met – and their four children during my boyhood years. My regret now is that I never took the time to know my Uncle Roy during my adult years and the loss is mine. How ironic and tragic that as I pen this blog, polio is rearing its infectious ugliness owing to lack of polio vaccinations not sustained during the Covid-19 pandemic; I can remember getting my polio vaccines in school during the 1950s, each time cognizant of my uncle’s affliction. I believe the polio vaccine was administered orally in little paper cups as depicted in this image:

Back to strawberry-picking. I suspect my sisters and I spent more and more time in Simcoe either at my aunt and uncle’s home or at my Grandmother’s farm some 7 miles west of the town owing to my mother’s illness in the mid-1950s and her eventual death in 1957 (see, my very first blog, in 2018, At Stake re my mom). Thus, some late Spring or early Summer in that time period, my Uncle decided it would be a good idea for Richard and I to earn money and launched us into strawberry picking…

I have no pictures of me or us picking berries but this lightly-tinted one reminds me poignantly of my experience harvesting my favourite fruit. Simply put, I hated it – the job, not the fruit itself. The disturbed wince-look on the boy’s face could easily be mine. I can still feel the papyrus-like texture of the wooden, quart-size, boxes, like these ones stacked upside down…

At first, bent over or sitting in the straw strewn between the interminable rows of berry plants and their interlaced runners, it seemed I had landed in snack-heaven and I know I ate so many, many berries kneeling or sitting in those patches. We were paid by the box though I cannot remember the going rate. At first, it was a challenge; eat only the shiniest, plumpest berries, save the rest in the box until 4 boxes were rounded-full in the carrier (see the wooden-handled-carrier cradled by the boy above) to be taken to and tallied by the farmer. Presumably, payment came at the end of the day. However, as the heat of the day increased, it seemed like the boxes took longer and longer to fill. Boredom set in quickly for me and the task became monotonous. After a few, what seemed like interminable days, I saw someone putting a box-bottom row of berries in their container, then rounding in a small mound of straw in the center of that row then placing berries around the straw to make it look like the box was full of just berries. I thought that was brilliant and an obvious way to beat the system, get paid, and who would ever know who did it! The fatal flow in the plan was the design of the quart boxes. With vertical air spaces on all four corners, it meant each box had to be shrewdly and ever so carefully packed with straw, the latter almost defiantly wanting to project its grainy tentacled-self into those spaces. I don’t know how long I was able to create my box-filling masquerade; however, I was all too quickly discovered and my transgressions reported to my father and my uncle.

And I don’t recall the exact conversations and chastising that must have eventuated when we were extracted permanently – and thankfully – from that job but I rather suspect it might have been one of the many times I heard my uncle’s retort, “if a job’s not worth doing well…” The immediate lesson to my boyhood mind at the time was this was not a job worth doing at all, never mind doing well. Strawberry Fields Forever, chanted the Beatles in 1967 and then as I do now, every time I hear that tune, my boy-body remembers just how forever it seemed to be in strawberry-picking fields. Years later, whenever I took my sons berry-picking at Millar’s Berry Farm in Lambeth, harvesting just enough for eating purposes at home, my mind flashed back to my very un-halcyonic childhood days of straw-deceit.

Happily, I think, my criminal-like strawberry adventures did not transfer into other jobs. While living in Exeter, Ontario in the late 1950s (amusingly, renting a house in Simcoe Street), one of my boyhood friends, Billy Farquhar’s father owned a bowling alley, Exeter Lanes, if memory serves. This current image of the facility does seem like the front of the lanes, very much as I remember it in terms of its size, the counter-areas etc…

The “Est 1945” beneath the Exeter Bowling Lanes inscription suggests this is the venue in its modern, candle-pin-popular form. I spent a lot of hours in that building, trying my best to imitate – ever my favoured way of learning anything in life – Billy’s prowess at the 5-pin bowling game. Billy’s dad let us bowl for free when the lanes weren’t busy with customers. If we had to do so, we bowled in socks but if we could, we grabbed shoes from the colourful array of size-labelled shoes like this 1950s-style pair from behind the service counter…

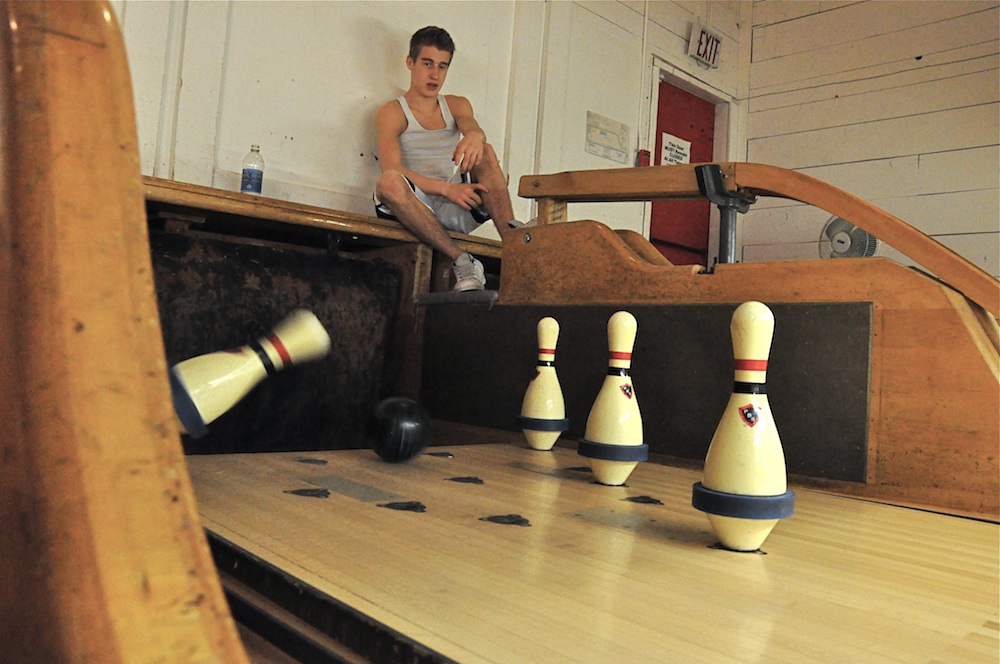

I don’t think automatic pin setting machines were common until the late 1970s. During the 1950s and 1960s when I revelled in the five-pin game, pin boys – if there were pin girls at the time, I don’t remember encountering them – were ubiquitous in bowling facilities. I became a pin boy and loved the job. We sat perched at the back of the lanes just as is depicted in this photo, ostensibly taken in 1951:

I am not the boy in this photo and I have to wonder about its 1951-ness given the water bottle and the style of the boy’s shorts. Nonetheless, the venue, the pins, and the alley all seem authentic to my memory of the era. The pins in this photo are five-pins complete with the rubber ring encircling the widest parr of the pins’ circumference. Note the triangles marking pin placements for either 5-pins or 10-pins. In the two facilities wherein I set pins, there was a barrier that extended from the ceiling such that the pin boys could not be seen, just like in this image of ten-pin games taking place:

Customers could see our hands and arms when we were re-setting pins but otherwise we were not visible.

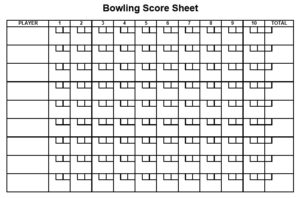

I was paid 5 cents “a line” for the five-pin game and 10 cents a line for the 10-pin game. A “line” referred to the 10-frames on the paper score sheet line corresponding to each player, like this sheet…

Theoretcially, this sheet displays 9 lines, the scoring for 9 players or for multiple games for a smaller number of players. Each line contained 10 frames or 10 times each player bowled during one game. Each player’s score was pencilled into each frame and then tallied into a total at the end of each line. At the end of whatever number of games customers played, they would take their score sheet to the manager who would mark the alley number, time of the game/s, and the name of the pin boy/s. For making the most money, it was best to set pins in the evening or on weekends when most people had the time to bowl and to be assigned two alleys at the same time. Also, league play meant teams of 4 or 6 would play several games translating into more lines for us pin boys. In the image of the boy sitting behind the pins above, he is positioned to set pins for lanes to his left and to his right.

Pin-setting was an art and a real challenge for me in terms of the dexterity and speed required. The “pit” at the end of the lane was about a foot, maybe more lower than the top of the lane itself. Pins knocked down by bowlers and the balls they delivered collected in that pit. My job at the end of each bowler’s frame wast to jump into the pit, grab either one, two or three balls setting each ball on the ball return rack with a gentle shove to deliver them to the front of each lane for the players. In itself, the ball return required just the right touch because the balls were only gravity-driven and had to make it up from floor level to come to rest at the raised portion of the ball rack adjacent to the bowlers’ delivery area. If it didn’t have enough speed, timid pin setters had to walk up the gutter to retrieve the ball. After the ball return, the next step was literally a step when I would set one foot on a lever at the base of the lane. Once depressed, that lever caused metal prongs about 2 inches long to pop up at the triangular markers so that the pins, each with a drilled hole in its base, could be placed precisely in the correct spot for the next bowler. With one foot firmly on the lever, the art was to grab and hold as many pins at their necks or narrowest circumference as possible between my fingers, ideally 3 in one hand, 2 in the other all the while reaching forward with my free leg to set each pin in place as quickly as I could.In the image below, the pin setter’s left foot is depressing the lever and the metal projections can be seen on two of the ten-pin markers near his left arm:

There was a cadence and audible, kind of light clacking rhythm to setting 5 pins each on the extended projections, starting with the centre, head or so-called # 5-pin, then the two # 3-pins, and then lastly, the 2 # 2- or corner-pins (the pin numbers corresponded to their scoring value), my torso receding with each pin or pins’ placement. As the 2-pins were set in place and with deft timing, one would release the foot lever causing the floor projections to recede and jump back to the seated position or into the adjoining lane to repeat the process. Occasionally, a pin or two would fall down if the foot lever were not foot-retracted with just the right pressure release, a situation easily and quickly remedied.

When setting two lanes simultaneously, we were busy literally jumping from and into adjacent pits trying our best to coordinate games so that players were not kept waiting. Kibitzing customers were not appreciated in terms of how much they would disturb our two-lane timing. It wasn’t hard work, just constant. People seemed to respect us although they rarely saw more than our arms. The only ‘danger’ in the job was from smart-aleck bowlers, always men who actually tried to hit us with the pins. In the 5-pin game, you had 3 chances or 3 balls in each frame to try to knock down all the pins; a strike was counted if all the pins were knocked down with the first ball, a spare if all the pins were tumbled on the 2nd ball, and 15 points if it took 3 balls to knock down all the pins in one frame. If 3 balls were delivered without all the pins dropping, the player’s score was tallied by pin number of those pins that had been knocked down. Men or males often prided themselves on how fast and hard they could deliver the ball. When one of the 2-pins were left, some of those speed- and power-cravers seized the opportunity to hit that pin so hard and at just the right angle to cause the pin to jump upward toward and perhaps careen into the pin-boy seated between lanes. We quickly learned who those players were and to be mindful of those who targeted us. When they witnessed such behaviour, proprietors would chastize the offender/s and if they did it more than once, they would be suspended from playing.

If we weren’t pin-setting and if Billy’s father premitted it, we would use our spare – pun intended – time to bowl ourselves. The issue was taking turns pin-setting. Once a week, we were paid, in cash, all based on the number of lines attributed to each pin-boy. If I kept track of my lines, I don’t remember doing so; instead I suspect I trusted Billy’s father. While ten pin lines paid twice as much, setting up ten pins was harder, more time-consuming; I preferred 5-pin and did both games’ setting. When we moved from Exeter to London, I continued to set pins near our house in east London (Dundas and Highbury intersection). The then newly-built Eastown Plaza with its second floor Arcade bowling alley was about a kilometer from my house. I set pins in the summer preceding as well as during my grade 9 year, 1962-63 and I remember two things more distinctly than other job-related memories that year: one, getting paid cash in small, brown envelopes a little bigger than dollar-bill size (like the ones bank tellers often use to give to customers who withdraw cash), always intrigued by how much money I made; two, after my pin-setting shift, I frequented either the Sard restaurant in the Eastown Plaza or I went to the lesser known restaurant – whose name escapes me now – near the Ford dealership closer to my home. The culinary attraction was singular…both restaurants served superb, golden-brown, and crisp french fries with gravy and I was addicted.

I quit setting pins at the end of grade 9 though my interest in bowling itself remained as a recreational outlet occasionally, never in competitive leagues. When I was a student at Western, I remember the old weight room in the very lower level – the bowels or dungeoon – of Thames Hall, the PE builing where I worked. Long and narrow with very poor ventilation, it served as the only weight-training facility on campus during the 1950s and 1960s. From the time I started using it, I was curious about its configuration – why such a narrow structure. A little research uncovered that the building’s founder and greatest advocate, PE Director John Howard Crocker planned to have that area used for a 2-lane bowling alley, a desire that never came to fruition other than the cement shell for the facility. Perhaps they ran out of funds in the post-second world war era when Thames Hall was created (1947). For me, I delighted in knowing we were training in a space intended for bowling lanes and I reminisced about my connections to pin-setting when I worked out in that odd room. Years later, I became aware of all manner of bowling interests among ancient cultures and all kinds of variations like lawn-bowling and a unique outdoor bowling game played by miners in the northeast of Britain. At the other end of the socioeconomic scale, many estates in the western world built elaborate, exquisite bowling facilities that were works of architectural art…like this grand two-lane facility somewhere in Britain:

I made lots of friends in my boyhood pin-setting days; in particular, the joking, taunting, cajoling among busy pin-boys perched across the back of the lanes made the work fun. In retrospect, setting up pins was athletic for me, kind of a self-challenge sport – how fast and how well could I do the job each time in the pit. I don’t recall how we were assigned lanes or what method was used to get us to come to work or if we just hung out waiting for the lanes to get busy. More than a decade after my pin-boy days, setting pins became more and more automated, eventually morphing into fully automated pin-clearing, ball-returning, and pin-setting mechanisms currently the norm. If one image in my mind’s eye and one feeling in my bones remain today, it is of sitting on that perch between lanes, kind of a pediatric king-pin self-satisfied, smiling gently in my boyhood revelry.

What replaced my part-time pin setting jobs was tobacco harvesting tasks delineated in my blog, Hanging Kiln. Something there was about crop-harvesting that seems attached to my earlier summer employments. To this day, out in the country north and south of our home in Kilworth, I ride my bike past various fields of tobacco, like this one on Carriage Road near Delaware…

Looking back on my tobacco years now, these acreages felt like, to borrow Sting’s lyrics, fields of gold, not literally but metaphorically:

Upon the fields of barley

You’ll forget the sun in his jealous sky

As we walk in fields of gold

I noticed when I took these pictures, sometime in late August that the sand or bottom leaves had been primed or picked, those leaves ripe enough for curing in the kilns. As I noted in my blog on this topic, I perceived my work in tobacco harvests during the 1960s solely as a summer job, never connecting the activity to the health hazards of tobacco use and addictions. And now, with acreages greatly reduced because of the health issues, in places where tobacco growing is still permitted (with acreages controlled or stipulated by law) southwestern Ontario, tobacco-producing farms are either resplendent with fields full of the ripening crop or replaced by other crops, like corn. And yet, many farms still retain dilapidated kilns like these..

Like moribund and morbid shrines, seeing kilns reminds me of my late summers in high school and flashes of tobacco-related memory-moments such as: hanging kiln or priming the crop; Swarfega hand-cleaner applied liberally at the end of each day; wet and sometimes, in early September frosty mornings; living alone in my grandmother’s farm house while she boarded and “handed” tobacco leaves on some distant farm; at 14- and 15-years of age, getting up in the pre-dawn mornings at her farm, walking out to the corn crib – the shed-like, open-frame structures wherein corn cobs were stored for drying as livestock feed – where the tractor was parked

and piloting it on the county roads some 4 km to the farm where I worked; driving tobacco-laden “boats” on trailers towed by that red Massey-Ferguson tractor; eating vast quantities of food served by farmers at lunch time; dating the farmer’s daughter, literally, when I worked at Roger and Laura Clarysse’s farm; and riding my Yamaha 80 motorcycle from Simcoe to various farms in early September pre-dawn hours.

I worked in tobacco for four summers during high school. It was hard work and great money; often, I earned more in 5-6 weeks of harvest than my friends made working all summer. Terrified of heights, there were times I struggled hanging kiln. However, much like pin-setting, there was a great satisfaction in filling a kiln each day, or, driving the boats from and to the fields. I revelled in the work, often staying two weeks into high school Fall term to travel to various farms to finish priming top leaves, the “gravy” or profit parts of the harvest that needed to be picked before first frost or hail storms. Either in July and/or at various times during those summer tobacco harvests, I can remember being recruited to help with harvesting hay for Simcoe farmers. It might have happened coincident with suckering tobacco plants as they ripened during July. When hay was ready, it needed to be cut and formed into compact, rectangular bales. Tractors pulled hay-baling machines like the one below…

The machine would gather the rows of cut-hay and compress and twine-tie them into rectangular bundles that were ejected from the back of the baler. Once the full fields had been baled, the job was to retrieve the bales and load them onto wagons…

Bales were rectangular and heavy. Wearing gloves to avoid cuts, we had to grab the thick twine encasing the length of the top of each bale, heft the metre-long bale to hip height, and then shuffle-carry it to the wagon where we knee-lifted it onto the wagon bed to the person who loaded the bales into stacks. The wagon was tractor drawn at a slow pace while we picked up bales about every 30 feet and it was sweaty, hard-work in the summer sun. If we could, we went shirtless and yet long sleeves meant better protection from the loose strands of hay that came out of the bales and clung itchingly to wet skin. The end of the process was to accompany full wagon loads to the barn and then off-load the bales onto a conveyor belt that sent the bales up to the loft for stacking storage, and eventually providing a reliable grass-crop food source for livestock:

For most farms, the whole baling process lasted only a few days. I don’t remember how I was paid or even if it were to help out, sans remuneration, a neighbouring farmer near my grandparents’ farm. I just remember the process and how lucky I was to be part of doing important work. I’m not sure if hay is still baled in this fashion; at one time, hay was harvested by horse-drawn equipment and ‘baled’ in stooks like this:

For most farms, the whole baling process lasted only a few days. I don’t remember how I was paid or even if it were to help out, sans remuneration, a neighbouring farmer near my grandparents’ farm. I just remember the process and how lucky I was to be part of doing important work. I’m not sure if hay is still baled in this fashion; at one time, hay was harvested by horse-drawn equipment and ‘baled’ in stooks like this:

Very likely, the hay was collected into those stooks with pitch-forks, a practice I suspect that goes back to harvesting in feudal times and probably isstill done on Amish and Mennonite farms. Today, hay fields are harvested by massive equipment that gathers the hay and machines it into huge and heavy circular ‘bales’ that require fork-lift equipment for pick-up and storage…

I do know that my tobacco and hay harvesting together with helping my grandparents on their farm [raising chickens, wood-gathering/cutting, and tending to their two huge gardens of vegetables and flowers] lead me to contemplate seriously becoming a farmer. I never did but I think I would have enjoyed that lifestyle.

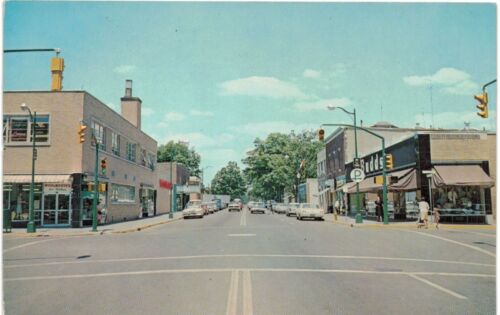

In the summer after grade 13, my Uncle Roy arranged for Richard and me to work in a factory instead of in tobacco. Roy was an accountant for a company in Simcoe called, I think, Canadian Coupling (& Fittings ?) although I can find no online record of that company or anything close to it even though it was a very large facility. The factory floor was huge with all kinds of machines, some of them very large, that cut and shaped steel. By that year, my grandmother had sold and moved from her farm (her 2nd husband, Grandpa Bruce Card had died 5 years earlier) into Simcoe to live in a one-bedroom apartment in Talbot Street. In previous summers, I would stay on her farm; however, her health wasn’t good and Roy asked if I would be willing to stay at a boarding house near Simcoe’s main thoroughfare, Norfolk Street, not far from the high school grounds. This is a post-card depicting downtown Simcoe during the 1960s:

My boarding house was about 4 blocks from this intersection. Many years earlier, perhaps in his late teens, my father worked as a clothing salesman either at the Budds’ Store depicted above on the right street corner or at some store near to that shop. I was aware at the time that dad had worked there and that he often spoke of working at the “British Knit.” My understanding was the full name was British Knitwear Ltd and I can remember how fondly he spoke of working in that factory and store that opened in 1927:

My assumption is that dad was in the retail end sold the knitted merchandise produced by mostly female employees on the looms and the large knitting machines at that venue. Whatever the case, for me, working at the coupling plant felt like both a new adventure for me and a connection to my father’s employments, the latter likely during the mid- to late-1930s in Simcoe.

I cannot remember the name of the woman who ran the boarding house but I do recall the rules about the times breakfast and dinner were served and that she prepared lunches for us to take to work. I paid the boarding fee from my earnings. There were 4 bedrooms with a common bathroom on the second floor in kind of a pentagon formation of rooms off of a large, central hallway and during that summer, I think the rooms were full. One of the boarders had a record player and in addition to the music LPs (Long Play vinyl records), he owned every record released up until that time of Bill Cosby’s comedy routines. Very sadly, at the time, we had no knowledge of the sexual assault crimes – ones that went back to the 1960s – for which Cosby relatively recently was tried, convicted, and jailed. In 1967, I could not get enough of listening to those 78 rpm records and often would come back to the boarding house at the end of my day-shift and sneak into my fellow boarder’s room (or did he give me permission?) and listen to those routines, howling with laughter, tears rolling down my cheeks. I saw Cosby perform at Centennial Hall in London in the 1980s and his humour and impeccable timing and facial expressions were stunning. In absolutely no way do I condone what Cosby did and I am very sad about the tragic impact he had on so many women. In speaking about his humour as a comedian now, I do so not to enshrine him but rather to remember how much the humour he created meant to me. His sketch of a ‘conversation’ between the Lord and Noah re building the Old Testament ark was my faourite. I can still hear the “voompa-voompa” wood-sawing noises that Cosby’s Noah produced while building the ark. I think and know now that his humour fed my story-craving imagination – I could visualize the characters and actions in Cosby’s real-life-hyperbolic routines. The Noah and the Lord skit was not ‘true’ and yet vivid in my mind’s eye and with ‘truth’ embedded in what it might have been like for Noah to build his ark.

My work at the Couplings’ plant was as intriguing to me as were most of my summer jobs. My main assignment each shift was to operate a machine that produced metal adapters and couplings like these ones:

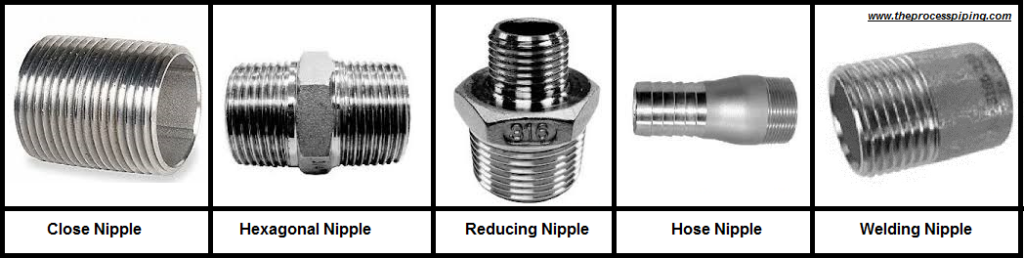

The second image of a coupling is most like the ones I remember making. These steel or metal adapters were used in hose connections, mostly industrial ones, I suspect. For reasons unapparent to me at the time, such adapters were commonly called nipples:

The hose nipple, 4th from the right was the most common one I produced, threaded at one end, layered flanges at the other. And there were other types I cut and shaped…

In plumbing and piping, pipe nipples were and are common connectors used to make a watertight seal when connecting piping to threaded fittings, valves or equipment. I had no idea what their use was in 1967; however, imagine what it meant to a 17-year-old young man to tell his family and friends that he made nipples at a factory.

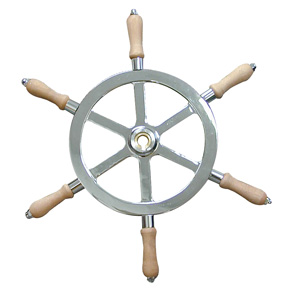

I wish I had a picture of the machine and work-area in which it was situated, but I don’t. We worked either day, 7:30-3:30 or afternoon 3:30-11:30 shifts, alternated about every 2 or 3 weeks. My work station and machine was a raised wooden platform on which my machine was placed. The device was all metal, perhaps 5 feet cubed and kind of a greenish brown. On each side was a thick metal wheel about 2-3 inches in thickness and perhaps 15 inches in diameter, each wheel affixed at its hub to and perpendicular with each side of my machine. The wheel had some 5 or 6 handles on it, sort of like ones you see on boats, like this…

One of the handles extruded longer, about three times as long as the other ones. The function of all handles was to turn the wheel easily to open and close small vices on the interior and at the front of my device, one on my left and one on my right as I faced the machine. Each vice was securely attached to metal runners or sliders that permitted the vices to slide forward and backward horizontally. On the right side, I would use the right wheel to open the vice and insert the raw metal piece of pre- cut-to-length pipe (each piece was anywhere from 3 to 6 inches long and perhaps 1 and 1/2 inches in diameter), then tighten the vice. About 6 inches in front of each vice were extremely sharp metal cutters designed to create either the threaded or flanged end of the pipe. The wheel handles were precision-placed so that the operator/me grabbed the long handle to kind of body-lean and push the pipe-containing vice on its runners into the cutters with just the right amount of force to engage the metal with the rapidly rotating cutters. The cutters were probably turned on as the vices started to slide forward; perhaps they were in constant motion but from a safety perspective, something must have turned them on and off. Oil was projected constantly through metal tubes onto the cutters to reduce the friction between metal surfaces and ease the shaping of the adapter end. Once the cutters caught or engaged the raw material, I did not have to apply pressure at all; the machine cutters whirred pulling the pipe further along the cutters to create the desired end.

When the shearing noise stopped, the cutters receded from the pipe and I would back the vice away from the cutters. Wearing relatively thick rubber gloves, I loosened the vice using the long-handle of the wheel wheel and with my other hand removed the adapter, one end finished. Holding the removed piece in my left hand, I inserted the next raw pipe into the right-hand vice with my right hand, tightened it, and then eased the new adapter into the cutters. As the cutters worked on that new piece, I shifted my weight slightly to the left and put the finished end of the first piece into the left vice, the raw end protruding toward the cutters; then I tightened the vice with the left wheel and eased the left vice encasing the pipe into the left cutters until engaged, then released the pressure. By then, the right one was finished so I went back to my right to begin the right-to-left cycle again. Raw, cut pipe was in a bin on my right and the two-ends, finished pieces went into a bin on my left, to be inspected for quality by the floor supervisor on a regular basis.

The work required precision and timing; each piece had to be set in the correct position along its length in each vice. The cutters would have sheared my fingers with any wrong move so paying attention was paramount in my mind. It was piece-work; counts of the finished product determined my pay. It took a week or so to get the timing down to an art and as always, that was my challenge, the job enhancement I always sought. The plant was either unionized or had work performance standards. Each machine – mine was the only nipple-maker but there were many other machines on the factory floor – had work-rates or quotas for output, kind of reasonable expectations of production each shift. If those were pointed out to me when I started, I don’t recall being told about them; however, I very quickly found out from full-time employees. I certainly knew that the more finished adapters I produced, the more money I made. By my 2nd pay cheque, I was commended by my managers for my performance and output. On the floor, I was leered at until 2 employees took me aside and explained that I was busting the rates, nice for me but for regular employees it meant work expectations would rise dramatically and that was not fair to them. I was told exactly what the quotas were for each kind of adapter and the precise number by which I could exceed those and still stay within prescribed expectations between management and workers. I empathized, I think, and I remember the quotas being just high enough to make the job interesting even though less of a challenge and monetary incentive for me. And I was very fortunate; Richard was assigned to one of the tapping machines where 7 vertical drilling mechanisms ‘tapped’ coupling cores. That machine required a constant, stooped position and just meeting the production rates was extremely difficult.

For my machine, presumably, the number of pieces of each kind of adapter was determined by orders and existing inventory. I never knew; I just made the number I was told to make. With each different adapter, the cutters had to be replaced, or re-set in order to make each adapter end specific to the different adapters (see the images above). Sometimes, with larger orders, the cutters had to be sharpened. Occasionally, the cutters would malfunction and have to be replaced or re-tooled. I was taught how to replace the cutters but breakdowns required me to contact one of the employees in the machine shop. My machine and I happened to be closest to one end of that shop such that when breakdowns did happen, I could call out to the mechanics; one of those men, Paul and I became good friends, at least during our shifts. Short and wiry-of-build, with curly blonde hair, perhaps 40 years old, Paul had a great sense of humour and I told him about the Cosby records and the Noah skit. Thus, each time I called ‘Paul’ in a loud voice, usually with his back to me, he would look up to the ceiling feigning that the Lord was calling his name. Having a sense of humour and enjoying that humour was important in all my summer jobs.

There were situations in this factory job that were part of my responsibility as a machine operator. For example, I had to get the raw materials for each order; clean the metal scrapings from the bottom of my machine and dispose of them in the machine-waste area; re-fill the oil receptacle with the oil that cooled the cutters; keep my area clean etc. The main, non-adapter job I had at the plant was that I was always the person on-call to get the raw steel pipes and take them to the huge cutting machines located behind me. The metal pipes were stored outside the rear door of the shop. When an operator needed pipe, I had to shut down my machine immediately and grab an electric, button-operated panel that was attached to ceiling runners by cables and, in turn, those cables to a hook holding a set of chain-metal straps or a sling that looked something like this:

My sling was 2-slings attached to a hook which, in turn, was suspended from a very thick cable running through a steel pulley at the top near the roof. The belt itself was very thick, expansive, kind of chain-mail material easily an inch thick and perhaps 15 feet long and 8-10 inches wide. At shoulder height, with one hand guiding the suspended sling and the other operating the electric device, I walked the sling out to the yard, found the stacked steel rods, undid one end of the sling and slid that end under whatever number of pipes was needed, say 15-20 metal pipes each about 20 or 30 feet long. The sling had to be spread out such that each ‘arm’ of the sling was fanned out from the approximate center of the stack of pipes in order to lift the raw material. Using the electrical panel, I would slowly tighten the two arms of the sling to take up the slack until the sling-encircled pipes started to lift, each end kind of sagging from the weight. It was obvious right away whether or not the load was in balance; if it wasn’t, I lowered the strap, re-adjusted the two arms and then hoisted the load. A sheer guess would be that each load of steel pipes probably weighed a ton or more.

With the pipes slung at about chest height, I would walk them back into the shop with one hand on one end of the load such that the pipes came into the shop floor aisle length-wise, taking up less space than width-wise and more importantly, making my ability to see other people and avoid collisions much easier than being blinded by a horizontal set of bundled pipes. Once I reached the designated machine, I turned the pipes such that they were parallel to the machine’s loading racks and then eased the pipe-load onto those racks, releasing the straps once the racks took the weight. I enjoyed the task; it brought variety to my job. And there was risk to it. On one occasion when being taught how to do this job, I slipped under the load of pipes to manage the transport better from its other side. The employee teaching me, put his hand firmly on my shoulder, riveted me in eye contact, and told me to stop and very sternly warned me never to do that again. What if the strap failed or the load slipped when I was under it, he said so carefully. I never forgot his lesson and always respected the dangers of that job and its safety-first protocols.

The coupling factory work lasted about 10 weeks that summer. About every 2 weeks, another student and I would be offered an astronomical sum of money (though I can’t remember the amount now), to put on long rubber boots, strip off our shirts and descend into the pit where the massive amounts of waste metal tailings gathered from all the factory’s machines were dumped. We had to shovel and/or pitch-fork these oil-ladened scraps into huge bins which, when full were hoisted up and out of the pit and taken away in trucks to some disposal site. It was hot, sweat-dripping, labour-intensive work that we did outside of our regular shift hours. The oil from that job and from working on my adapter machine seeped into clothing, especially my pants, and our skin pores. For some years after that summer, little oil-filled pustules would appear on my thighs, to-be-popped remnants of my coupling labours.

At the end of my first year of university, the spring and summer of 1967, I secured a job at Emco in London. Its full name was the Empire Brass Company currently with some 140 sales’ locations across Canada, one of the largest providers of plumbing and heating supplies. These two images pre-date my work for the company but they give a good perspective on the size of the enterprise…

I had two separate jobs at Emco that summer. One was probably the most tedious one I ever encountered, just so rote and unrewarding in its requirements. Copper tees – and other copper products, like copper elbows – were produced in prodigious quantities. The finished products looked/look like these…

To manufacture and shape the tee meant that the shell had to be shaped and forged around a lead core. I don’t think I ever saw the machine/s where the tees and elbows etc were shaped; nonetheless, huge containers of the lead-filled copper fittings came to my work station. The latter was basically a huge fireplace or kind of oven, mostly black in colour. In some ways, it looked like an over-sized cooker for french fries. A huge ‘sink’ almost filled with boiling, black oil, had hooks for heavy baskets that looked just like french fry cooking-containers. Armed with asbestos gloves, I transferred tees into the baskets perched above the oil. Once filled to the ideal level, using all of the baskets, some 4-6 side-by-side, I then unhooked each basket and lowered it/them into the boiling oil. I don’t remember how long it took, maybe a matter of 15 minutes depending on the number of immersed baskets. The oil melted the lead into lava-like liquid. I would lift each basket to see when the tees were lead-emptied. Then, I went around to the back of the cooker, set empty moulds in place under a long steel (I think) pipe that extended from the very bottom of the machine, one end of which extended over the moulds. Releasing a valve on the furnace-like machine and with a hook holding the far-end of the tube, I could release the lead-lava that had sunk to the bottom of the sink into its drain without any of the oil – not sure how the furnace ‘knew’ how to do that separation – and direct the tube over each mould until the moulds were full. Once the cooker was emptied and the moulds were full, they were cooled in the air and eventually taken back to the copper-tee-making machines for re-use. The now-empty copper pieces I dumped into bins to be fork-lifted away when full; the copper did not retain any oil that I remember. For weeks, my entire shift was comprised of seemingly endless cycles of repeating this task, the only challenge being to avoid burning myself badly. There was no incentive, just manual labour. I wore a very thick apron and I remember it being extremely hot in a non-air-conditioned factory. And that heat turned out to be a temperature foreshadowing of what was to come later that summer.

Happily, a job came up at Emco in another part of the factory. Along the length of a conveyor belt were a series of core-making machines, the larger of which were called BPs or Duals, no idea of the reason for the names. My machine was the smallest one. I don’t remember much about it except that it was much smaller than my adapter-making machine at Canadian Coupling. In essence, there was a cylinder about 18-inches long and 5 or 6 inches in diameter. I filled it with a very fine, sand’-like mixture, then capped and sealed the tube. With the handle on one side, the cylinder could be flipped 180 degrees to inject a precise amount of sand mixture into a metal, 2-piece, vice-like mould. The mould sealed itself once injected and steam-heat was combined with injected resin, all from buttons I pushed in order to form the mould into a solid shape about 5-10 mm in thickness. Once the injections were finished, I flipped the cylinder upright, released the mould, and removed the finished core with asbestos gloves, placed it on the conveyor line and repeated the process. The cores were put in bins of some kind at the end of the line and then used as templates to shape machine metal parts for automobiles, valves, or machine tools in another work location. The core machine work intrigued me; it required precision, timing, and becoming accustomed to regulating the injections to create a high quality product. And it was piece work that could increase my hourly wage. Students like me worked alongside full-time employees who were kind to us in offering help, teasing us, and making the days more enjoyable than had been the case on my boiling oil, lead-draining furnace.

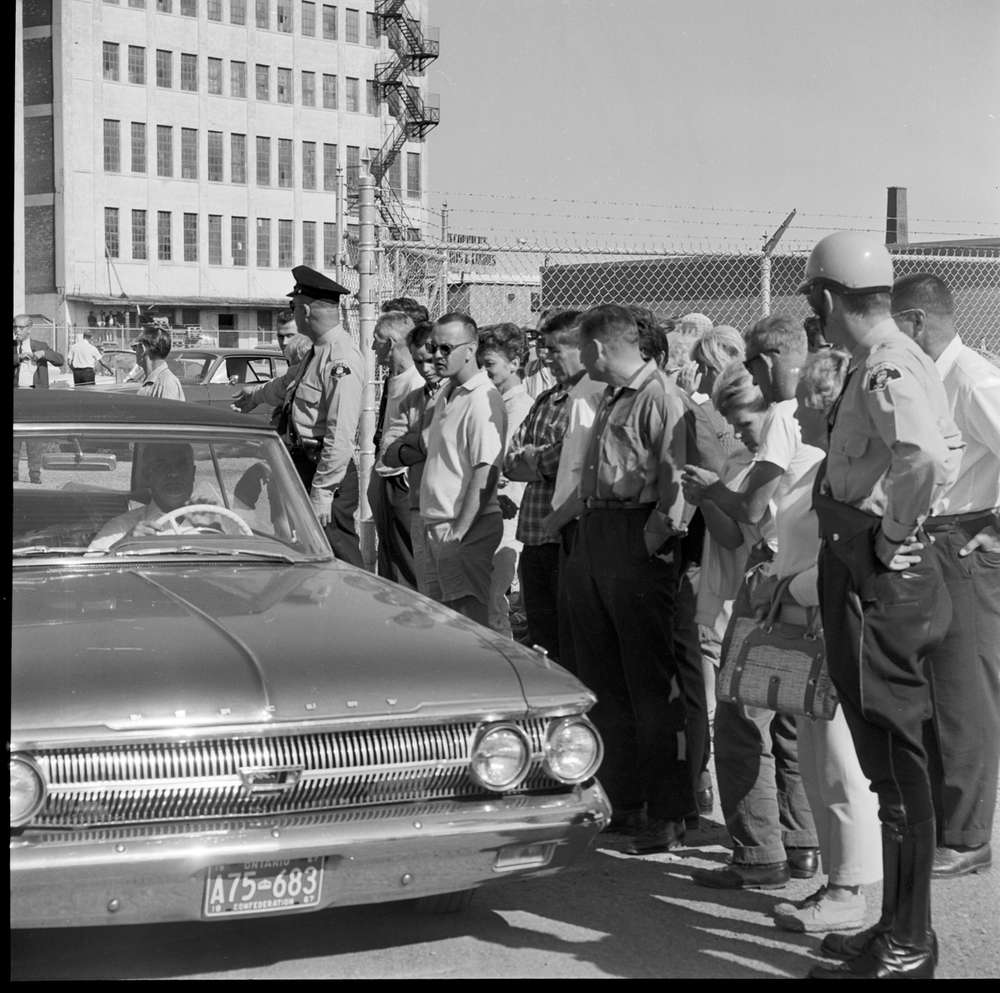

I would have been quite content to finish the summer working on the core machine. However, part way through August, the union workers at the plant voted to go on strike. It became quite contentious with ‘scabs’ hired as the strike dragged on for some 6 months …

Non-union workers had to be escorted by police through the picket lines. We were advised as students not to attempt crossing the lines; it just wasn’t safe. I was really counting on the money from those last 3-4 weeks of employment and searched for other work. A friend told me they were looking for workers at Superior Concrete in Lambeth, a small town just south of London. I applied and was hired right away.

The concrete plant made cement bricks and blocks of all sizes. A huge machine inside the warehouse was operated by skilled workers; it reminded me of images of large blast furnaces. Raw cement was poured into the machine. The operator pushed a series of buttons and manipulated handles of all kinds, all of which were in service of shaping the cement into the appropriated sized bricks or blocks. The image below is a bit smaller than the very large, green one I remember at Superior. Current brick- and block-makers are all automated…

The process required intensive heating of the cement and I assume some kind of resin or hardening substance was used as well. The extremely hot, finished products were hydraulically set on very thick metal trays that the machine operator, in turn, could withdraw from the machine using electronically controlled grips. We had very little to do with this part of the process. However, indelibly imprinted on my memory is the image of occasions when the machine operator had to re-tool the concrete-forming dies inside the furnace-like machine. To do so, he had to make sure the machine’s power was turned off and then climb right inside the machine to do the changeover. Operators had a person they most trusted stand in front of the machine armed with a lead pipe or other weapon; that guard had clear instructions to hit anyone who came anywhere near the machine while the operator was inside. We were sternly warned to stay back during these re-tooling operations – we had nothing to do during such times – and I remember thinking these people risked their lives climbing into the machine – not sure I could have done that.My job was hard labour after the bricks and blocks were formed.

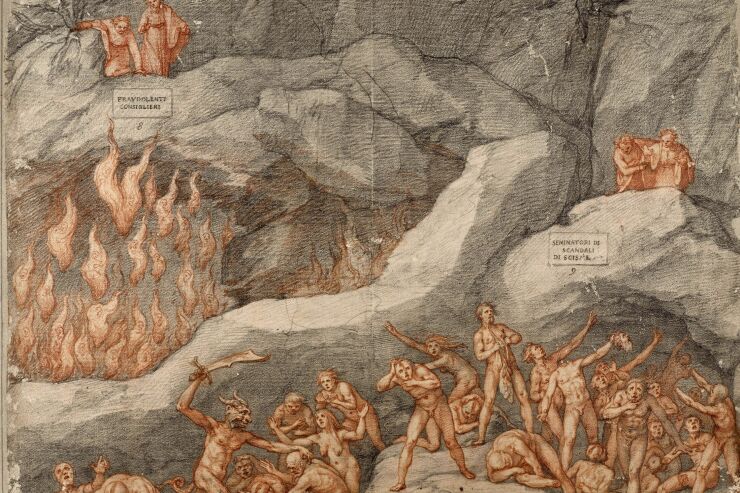

The trays were set onto metal racks kind of like racks of bread that you see in bakeries; each rack apparatus could hold 5-8 levels of trays, depending upon the height of the manufactured raw bricks. Once a rack was loaded by the operator, a fork-lift truck brought the racks out placing them in a line outside. The machine and its operator turned out the bricks/blocks very quickly, likely related to keeping the cement from hardening inside the machine. Within minutes, there were lines of trays, each one about 7 to 8 feet high containing the bricks. Between the trays and racks were placed wooden pallets. Each labourer = me had to stand in front of a pallet and transfer the bricks/blocks onto the pallet and stack them a certain height. The bricks were steaming and radiated heat; coupled with the August humidity and the sun, it was the hottest work I have ever experienced. With asbestos gloves, I removed the bricks from the trays starting at the bottom tray and worked my way up. We actually preferred 12-inch concrete blocks for stacking. Although heavy and hot, because of their size, we could do the job quickly, move to the next tray and pallet and finish the task relatively quickly. What we learned to hate were the trays of bricks that were the size of bricks used in building houses. Though we could pick up two a time, it seemed to take forever to finish a tray; bent over for the most part, it was very hard on the back, constantly moving up and down to load the pallets. Once a tray was emptied, we could almost feel air circulating. During that academic year, in English 021 at Western University, I had studied Dante’s Inferno, a story of Dante’s descent, in 9 stages, into the fires of hell and remembered some of the books’ ghastly hell-images, like this one…

I believe I experienced that kind of inferno that summer. We were soaked with sweat all the time and I remember bringing a huge, picnic- and several quart-sized green thermoses of water. I refilled them several times each shift. We started very early in the mornings and often worked til late in the day, sometimes earning over-time pay if an order had to be finished. Along with tobacco-priming, I believe that job at Superior Concrete was the most physically taxing of my summer employments. I was over-joyed and so relieved when university’s Fall term recommenced in mid-September.

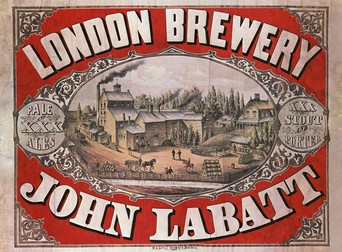

In sharp contrast to almost all of my jobs to that point, my next three spring/summer jobs were just so easy, even delightful to do. I applied to work at Labatt’s – the Labatt Brewing Company, ironically to me – from my family-time and summers spent in Simcoe, Ontario – located in Simcoe Street, London. I could have been assigned to all manner of menial jobs in that plant; somehow, the labour gods smiled on me and I was assigned to work in the shipping area. Labatt’s and London have a long history in the brewing industry, a lot of that history romanticized in images like this 1870 lithograph of the brewery in its infancy…

And one corner of the immense building as I remember it …

In essence, my job was to load beer cases onto the distinctive-looking, beer-coloured Labatt trucks like this one…

The shipping truck-bays were located on the southeast corner of the factory. 4 or 5 trucks at a time could be backed into the bays. Normally, the trucks contained any number of pallets, up to 18 or 20 of them, each pallet stacked with rows of cartons containing empty beer bottles – like the image of one below – that had been gathered from various Brewers’ retail outlets on the drivers’ routes…

Often, the truck stank of residual stale beer in the empties, as they were called. The job was to unload the empties and then re-load the trucks with orders from beer stores across the country.

As full-time employees took holidays, university and temporary workers were hired to replace the vacationing workers. We had to buy white, short-sleeved shirts, green cotton pants, and steel-toed shoes were mandatory. At the start of each shift – day, afternoons, or all-night ‘graveyard’ shifts were rotated each week – the shipping supervisor, always impeccably dressed in long sleeves and black pants, part of the management team style, paired each of us with a full-time employee as well as to a particular shipping bay. He also named 3 students, rotated each 8-hour shift, to work in the “makeup” area. Behind the bays and loading docks were rows and rows of beer cases – 12-packs, cases of 24, all sizes – stacked rows, 8 boxes/cases high on pallets such that the top row was about 6- or 7-feet in total height, from floor to the top of the boxes on the top row. The beer-case-laden pallets, in turn, were stacked 3-high in the long rows:

Most pallets contained one type of beer or ale, pilsener, lager, ale of all varieties. For those of us assigned to the loading docks, one person drove a fork-lift truck for half the shift while the other person worked the large, battery-powered, hand-operated pallet “truck” kind of like this one…

Via the buttons on the handle, the operator could lift and move loaded pallets from and into the transport trucks. The job of the pallet truck operator was to unload the pallets, one at a time, leave the unloaded pallet on the loading dock directly behind the truck positioned in such a way that the fork lift truck driver could easily pick it up and deliver each pallet to a redistribution area where the empties were unloaded, the bottles cleaned etc by workers in another part of the factory. Once unloaded, the process was reversed to load the truck with pallets of beer cases. The fork lift trucks were manual transmission, propane-powered and looked something like this one…

Via the buttons on the handle, the operator could lift and move loaded pallets from and into the transport trucks. The job of the pallet truck operator was to unload the pallets, one at a time, leave the unloaded pallet on the loading dock directly behind the truck positioned in such a way that the fork lift truck driver could easily pick it up and deliver each pallet to a redistribution area where the empties were unloaded, the bottles cleaned etc by workers in another part of the factory. Once unloaded, the process was reversed to load the truck with pallets of beer cases. The fork lift trucks were manual transmission, propane-powered and looked something like this one…

Simply put, I loved this job over the entire 3 summers that I was employed at Labatt’s. Driving the fork lift was a joy and it required skill especially in that it was the back wheels that turned, not the front. The hard-rubber wheels seemed to have good traction on the cement floors. The lane-ways among the stacked beer pallets were easily wide enough for drivers going both directions while carrying full loads and there just seemed to be a code of care and safety especially negotiating corners with drivers kind of peering out over the top of the load. The gear shift was horizontal, to the right of the steering wheel and the clutch was easily engaged and released – I don’t remember drivers stalling at all. If we were given formal training on the trucks, I don’t remember it, more baptism by fire. Two vertical sticks with yellow knobs controlled the operation of the forks; one raised and lowered the actual forks while the other tilted the frame (black in the picture above) back and forth dependent on the angles needed on the forks for picking up loads, carrying them, and setting them down.

The rows of beer cases on pallets were numbered on huge signs above and at the front of the rows. Picking up a pallet from the floor was easy; the real art was getting the 2nd and especially 3rd ones that were stacked on top of each other making the rows very high. Drivers didn’t know until they got to the row – we were given a sheet telling us the brands by row at the start of each shift – whether the pick-up would be the bottom pallet, middle one, or the very top because all the other drivers might be seeking the same brand. I had to get accustomed to getting the forks at just the right height and correct level to slide into the stacked pallets.This is a more modern image but it provides a good visual of what was entailed in picking up the pallets of beer:

For the pallets on top, the forks were easily 20-24 feet above eye level. Great care had to be taken to insert the forks at exactly the right height and angle into a pallet-space about 6 inches in height, ease the truck forward until the back support of the forks just touched the beer cases, then slowly raise the load and at the same time tilt the load very slightly back so as not to catch the beer cases on those cases behind the pallet being retrieved. Adding to the challenge was the fact that the rows of beer-laden pallets were probably 16-20 pallets long. If the row were close to being emptied, then I had to drive into the designated row with a row of full pallets, 3-high on either side of me, kind of like being in a beer-framed cavern. Once the top pallet was loaded, I had to back away just enough to lower the load almost to the floor without touching the beer cases on top of the 2nd pallet of beer or any other cases on the way down. Checking that the load were stable, forks angled back about 10 degrees, the next challenge was backing straight out of the row though made easier by the rear-steering wheels than backing up a car. Once out, driving the full pallet forward was relatively easy. When back at the loading dock, the transport truck was big enough that we could drive the load right into the metal, corrugated cargo bed, set it down, back the fork truck out, and then go get another beer-load while the pallet truck driver came in and moved the loaded pallet tight to the wall buttressed against the previous load. A full cargo load was about 20-24 pallets in two rows along the bed.

The whole shift was a series of truck un-loading and re-loading. We had breaks in our work when drivers pulled out the loaded semis and backed in another truck. Adjacent to the loading docks was the make-up area. Each shift, 3 people would be assigned to that area. We rotated the tasks in that area such that one person drove the fork-lift, the other 2 loaded beer and we switched roles 3 times each shift. The task was to get beer-orders from the supervisor, orders that were for smaller towns’ beer stores where they required smaller numbers of beer cases in smaller sizes. And, in pre-craft beer days, some lesser known beer types’ orders were smaller than a full pallet. The driver would retrieve a pallet of beer, bring it back to the two people on the floor who would then take the required number of cases and load them – it was called, “hand-bombing’ – onto a pallet. It was time-consuming and had to be done in a particular order such that the truck drivers could retrieve the beer for each store in the order in which the towns would be visited along their driving routes. Thus, there was a lot of waiting time on that job and shifts seemed to go slower even though the kibitzing opportunities were greater.

At the back of the shipping area were giant, beer-case-stacking machines. Well above the floor and away from the stacked pallets of beer, were conveyor rails with long, metal-cylinder rollers, like this…

From some other part of the factory, the bottling and packing area would come sealed cases of beer ready for stacking and storing and ultimately, delivery. The belts ended at two stations where an operator at each station received the cartons, and using a suspended, horizontal ‘arm,’ pushed them onto a hydraulic, caster-lined shelf in front of them until rows corresponding to the surface area of a pallet were complete. Releasing the casters, that row of cases was set on the pallet immediately below; the emptied casters were then re-installed and the next row was completed; the process lasted until the 7 or 8 rows of beer were full. The full-pallet rolled out on casters to a pick-up platform to be retrieved by fork-lift drivers who stacked them in the rows. A few times, I got to do the work of the beer-case loading and it was fast work to keep up with the cases delivered along the conveyor belts; I suspect we were asked to do this when operators went on breaks. Interesting to me, the fork lift trucks for this job were bigger than the propane-driven ones and they were battery-operated. The protocol was the drivers of those trucks had right-of-way because they had to get back quickly for their next load.

Shifts over these summers were always enjoyable even graveyard ones. Part of the intrigue for me was getting to know and work with full-time employees who seemed to respect us even though they played all manner of tricks on us. For example, one of the battery-operated fork-truck drivers, Harry Bishop was, to me, the spitting image of Alfred Hitchcock. Round of face, small lips, quite rotund, he was the undisputed king of drivers. Quiet, unassuming, he always seemed to be kind of disinterestedly watching us, perched on his fork-truck throne. When we students were first learning to drive, Harry loved to wait until we got deep into a row retrieving a pallet of beer from the top or third row of the stack, a feat requiring our full attention. His battery-powered truck made no sound and he would deliver a partially- or fully-loaded pallet of beer and leave it on the floor behind us, then watch from a distance to see if we would back up too fast, unaware of the pallet behind our fork-lift truck. I think all of us were victims at one time or another of crashing into Harry’s pallet. The unwritten rule of the plant was you make a mess, you clean it up. Even if I didn’t hit the pallet going in reverse, I’d have to stop, take my truck out of gear and go get help from a fellow driver at the loading dock while Harry feigned ignorance. Floor supervisors seemed to go along with Harry’s shenanigans, all part of the working environment and culture of the job.

Labatt’s had a lounge area for its employees, as well as lunch rooms. A perk was that at each break, two 15-minute ones per shift, each employee was permitted to have 1 free beer. At lunch, each person was allotted 2 free beer. Thus, two-thirds of the way through a shift, some employees had 4 beers working their way through their systems. However, drinking on the job was commonplace though far more insidious. At the start of each shift, one of the drivers at the back, like Harry or those who worked with him, would get a block of ice – I never knew from where, perhaps it was carried in by the colluding transport drivers – put it in a metal garbage can and have bottles or cans of beer set on top of the ice and around it to cool the liquid. Surreptitiously, it was announced among the full-time employees where the can was hidden and they could visit the container for a drink when the supervisor was not around; all manner of signals were in place when the supervisor came back on the floor. There is no way supervisors did not know about this; we, as students knew but we were not allowed to take part, just by convention, I guess – perhaps we might ruin the arrangement, I don’t know. I have never liked the taste of beer, then or now. Thus, none of these break- or lunch- or stealth-beer drinking opportunities were of interest to me. It all seemed then as now to be kind of teen-aged behaviour re ‘hidden’ drinking behaviour. I do believe many of the full-time employees were alcoholics, not just in the shipping area but throughout the plant. By mid-shift, it was not difficult to smell beer-breath from many of the employees, a nasal-fact that could not possibly have gone unnoticed by supervisors. Over the summers I worked there, I had to be careful by mid shift re working with particular employees who were clearly inebriated and therefore less competent, in my view, in operating fork-lift vehicles. The only close-call I had was once on the loading dock when my drunk partner mistakenly put his fork-truck in reverse instead of forward. Had it not been for a very observant, quick-acting fellow employee who grabbed my shoulders and pulled me back, I could have sustained very serious injuries as the trucks were very solid and heavy in weight to counterbalance large pallet-loads of beer.

During the three years I worked at Labatt’s, most beer was bottled. Cans were just making it into the industry. The process for getting the newly-delivered, empty cans to the correct area of the plant meant going to an outdoor shipping bay. The empty cans arrived on pallets like these ones…

The process was the same unloading one though cans were so rarely used, they might make up one pallet on an order. Mainly then, it was just unloading the cans and taking them to store in rows in another location. As might be seen in the picture, there were thousands of cans on each pallet, each row separated by thin cardboard and the full pallet was usually strapped but not covered. I seemed to get more of my share of can deliveries and it always seemed the loads were precarious. Often, when we raised or opened the transport cargo doors, it was a mess of cans all over the truck floor owing, likely, to their light weight. In the same vein, unloading them with the fork truck was done above ground, not from bays where the shipping floor was the same height as the back of the trucks. The job of the pallet-truck driver was to use the device – that itself had to be fork-lifted into the back of the truck – to bring pallets to the edge of the truck bed to be fork-lifted up and away from the truck. It was precision work and it always seemed that we spilled at least one pallet of cans. When we did, we had to hand-stack them, a job reminiscent of my small brick-stacking days though much lighter and cooler work. When spills inevitably did happen, word spread quickly such that we were visited by laughing students and full-time employees eager to witness the event and mock us mercilessly.

The process was the same unloading one though cans were so rarely used, they might make up one pallet on an order. Mainly then, it was just unloading the cans and taking them to store in rows in another location. As might be seen in the picture, there were thousands of cans on each pallet, each row separated by thin cardboard and the full pallet was usually strapped but not covered. I seemed to get more of my share of can deliveries and it always seemed the loads were precarious. Often, when we raised or opened the transport cargo doors, it was a mess of cans all over the truck floor owing, likely, to their light weight. In the same vein, unloading them with the fork truck was done above ground, not from bays where the shipping floor was the same height as the back of the trucks. The job of the pallet-truck driver was to use the device – that itself had to be fork-lifted into the back of the truck – to bring pallets to the edge of the truck bed to be fork-lifted up and away from the truck. It was precision work and it always seemed that we spilled at least one pallet of cans. When we did, we had to hand-stack them, a job reminiscent of my small brick-stacking days though much lighter and cooler work. When spills inevitably did happen, word spread quickly such that we were visited by laughing students and full-time employees eager to witness the event and mock us mercilessly.

Over those Labatt years, I got to know a few of the full time employees quite well, even being invited to dinner with some of them. One employee had a pool in his backyard and after hot-weather shifts, he would invite us over for a swim. One employee, Doug, of whom I was quite fond, had two Doberman pinscher dogs that were magnificent and very friendly canines. Doug was a very smart man, probably in his 30s. He had a vision to start a 10-speed bike store and invited me to invest with him. I had no money to do so and couldn’t even imagine why one would need more than 3 speeds on a commuter bike; therefore I declined. Doug became a very wealthy man from his investment idea.

My last summer job as a student was as doing lawn-mowing at the end of my MA year, 1972. The work was with the Sault Ste Marie Board of Education, mowing lawns of all the elementary and secondary schools attached to that Board. Most of the job was driving a gas-driven reel lawn-mower. I had grown up pushing a reel mower not unlike this one..

My father had a belief that storing gas could result in fires so he refused to buy a gas-powered mower; I was the designated mower for a weekly task that was hard work pushing through grass, short or long. The rider one I used with the Board was huge and I am unable to find a picture of one like it, just a “gang reel” mower that at least illustrates the multi-mower configuration:

Instead of being towed, the one I used was roughly where the tow-bar is situated in the image above. Seated behind its engine, there was one reel behind the tractor and then on each side two more reels adjacent to each other. Thus, I could cut about an 8- to 10-feet swath with each pass on the large school lots. The side reels could be manually raised toward the engine – as they are raised in the picture above – for narrower areas. The job was of minimal interest and I had two tasks that summer. I was determined to finish my Master’s thesis in order to begin PhD work in Edmonton in the Fall. Thus, I sat on the reel lawn mowing machine all day and then sat at my desk all evening writing my thesis. I don’t think I ever had such a physically inactive period of time in my life and I gained almost 30 pounds due to my very sedentary summer lifestyle. Very much like my Emco lead-melting job, I found lawn-mowing to be rote with minimal challenges except for mowing the hill of Sault Collegiate High School…

The grass was never as long as it is featured in this image when the school was demolished in 2001. What is partially apparent in the image is that the hill was very steep and quite long top to bottom. What it meant for cutting was that I had to mow along the width of the hill, starting at the top; for the steeper portions, my co-worker, George Furkey had to stand and straddle the reels on the uphill side of the mower using his weight and my leaning on the seat edge to keep the machine from tipping. I make up that as I gained weight over the summer, the less was the threat to tipping.

Mowing school lawns was pretty repetitive work. The only variations were in doing machine repairs, blade-sharpening, and having to scythe overgrown portions of schoolyards, especially those of rural schools in the Algoma district. What did always interest me was my lawn-partner, George, a retired jack-of-all-trades. Simply put, George was affable and a bull-shitter. Sporting a toupee under his seemingly decades-old, tattered cap, he just loved to talk to anyone about anything. When introducing himself, he always said his last name, Furkey and then, “just like turkey, only with an F.” I heard that umpteen times over the summer. Most conversations he initiated began with, “I suppose…” and then he would get curious with the person/s with whom he was talking. Watching him was like spectating at live theatre; he was just so adept at managing conversations, making up stories, and engaging with anyone. At the same time, he was kind, fun to be with, good to me, and we seemed to respect each other. He did not like riding the reel mower and preferred to use the hand-driven gas mowers and do the trimming work while I did the main parts of the schoolyards. My preoccupation, literally that Spring and Summer was completing my thesis. I did finish it in late July and went back to London for my thesis exam/defense in late August. Doing lawn-mowing seemed like a means-to-an-end – make money for doctoral work – and I just didn’t engage with the work as much as I had in previous summer jobs.

My only other school- or university-years job was one where I stocked shelves in an Edmonton, Alberta liquor store over Christmas one year while doing my doctoral work. Similar to working in the beer industry, my only drinking alcohol interest was the odd drink of rum. Otherwise brands and types of alcohol were foreign to me. My job was just re-stocking labelled shelves. About all I remember from that work is how fast alcohol was purchased at holiday times and how quickly we had to work to keep up with disappearing stock.

All things considered, I enjoyed my summer jobs, some more than others. I did learn the value of hard work; in fact, I immersed myself in it. Part of that immersion stems from my capacity not just to endure work but to challenge myself to see just how well I can endure it. Stunning to me were all the inventions – like the core-making or nipple-making or brick-making machines contrived to fulfill societal demands. I was privileged to get know full-time, hard-working people who had no choice but to do the same tasks, days, weeks, months, and years on end, kind of a mid-20th century Hard Times (Charles Dicken’s mid 19th century novel) industrial legacy writ large in real life; I even gained some appreciation for the reasons some of them drank as much as the Labatt’s workers did. Physical work like that required for tobacco-harvesting, or picking up hay bales, or piling bricks simply appealed to my body’s craving for movement, making tasks efficient, even just sweating. I also know doing hard labour was such a respite from the more intellectual pursuits of high school and university classes.

Finally, I think my penchant and experience for summer work carried into extra work I did above and beyond my full-time university professor role. Beginning in the Spring of 1977 and for the next 30 years, I took on the role of fitness/wellness roles with the Ivey Business School at Western. The School hired me to work with executive business people in two, three-week, back-to-back courses each May and June. In addition to my graduate student responsibilities, committee work, and other responsibilities of my full-time job, I immersed myself as a kind of fitness advisor for the two executive education programs, the Marketing Management Course (MMC) followed immediately by the Productions/Operations Management Course (POMC). Dave Burgoyne, a down-to-earth, “downtown marketing man,” as his colleagues described him was a professor in the marketing field at the Business School. Dave, on one of my mentor’s, Mike Yuhasz’s recommendation hired me to instill fitness and wellness/health components within the business exec courses they offered. MMC typically recruited some 120 participants while the POMC garnered 60-70 people. All the participants stayed in two of the residences during the courses, Medway and Delaware residences. One of my roles was to hire graduate students as fitness instructors and meet the participants each morning, 6 days a week at 6:30 AM and take the executives for a run, jog, or walk. I offered 3 different levels of cardio-respiratory opportunities into which the participants self-selected, each group with a leader including myself. We would do warm-up exercises outside the residences and then do the aerobic activities. the picture below is from the late 1970s – I’d be guessing 1977 – with me in the purple sweatshirt taking a Business School executive group for an early morning run:

The idea was to get folks used to a fitness routine, one that they might carry into their lives post-courses. In reality, I think the business school profs liked the fact that the activities were compulsory; that translated into everyone having breakfast and getting to class on time. Daily, I would put up fitness motivating slogans on the notice boards outside their classrooms, just things to remind them about the importance of a health lifestyle. Often, these fitness phrases were more sarcastic than motivating, as I recall them now. For example, I stole from the Canadian government’s fitness program, Participaction’s logos, ones like ‘don’t run for the bus, you might not make it‘ and ‘roller skate your way to social ridicule.’ I also had an hour with them in class 2 or 3 times a week to talk with them, answer questions about things like nutrition, starting an exercise program, flexibility work, strength-training etc. In the late 1980s, when all the executive education courses moved to Ivey’s executive leadership and learning centre at Spencer Hall on Windermere Road (an off-campus facility inclusive of accommodations, completely self-contained as a learning centre) I was able to integrate programs like yoga into their course schedule.

Part of my learning from these annual summer employment Biz school stints was that derived from watching some of the best teachers I have ever encountered. Ivey’s professors taught exclusively via the case study method and to a person, they were wizards in the classroom, in my estimation. Whenever I could afford the time, with the profs’ permission, I would sit in and observe them teach. Their ability to work the room involving all students, to draw material from the cases studied and from the experiences of the executives were pedagogical lessons in learning engagement for me. At the same time, the money was, as my dean often opined to me, blood money in that I had to keep up my full time professorial work and do the summer jobs. It was exhausting at times; I can remember leaving my running clothes in the dining room when I got up at 6:00 every morning during those six weeks and often leaning up against the wall, half-asleep yearning to go back to bed. Working with the executives was a real challenge in that these were folks, like the full time employees I encountered in other jobs who had real-life experience, much different than the young students with whom I was accustomed to working. Nevertheless, the morning runs were highlights; shaving and showering in the older UWO, Medway residences with the (male) biz profs who joined the early morning runs was a highlight in that so much humour ensued. Dave Shaw, an accounting professor who was gifted with a razor-like wit used to sing Mac Davis’s 1980 hit “oh Lord it’s hard to be humble” while shaving and laughing and he could pull it off brilliantly. Often, participants would roast us profs at the end of the course. One year, they hired a cartoonist to characterize each of us. This was mine and I still have it…

![]()

As with all my jobs – save my nefarious strawberry transgressions – once I was on the job, I tried to give 100 per cent in all the tasks I did, perhaps living into my Uncle Roy’s “if a job isn’t worth doing well, it isn’t worth doing at all.” If I ever had to call in sick, I don’t remember doing so. With the exception of the Labatt’s job, my summer jobs were very physically taxing and tiring; of interest, off-shift or in the evenings, I read or watched television, too tired to do anything else when most jobs required that I be up at 6:00 am. Even in the boarding house in Simcoe, at 17 years of age, unencumbered by parental supervision and owning a motorcycle, the most adventurous undertaking I did was to visit my grandmother who lived 2-3 blocks away. As I finish reading this “tome” about my summer jobs, I am struck by how much detail I remember. I wonder now what safety standards have evolved in some of those jobs and if a young adolescent would be given the kind of living alone freedoms I enjoyed. My perspective is that most work was so repetitive that my body remembers and so the intricacies of the work are kind of imprinted within me. I look back now on all my summer employments, from strawberry-picking to Business School roles and I tumble home to the memories and think of the privileges of having those jobs, the people I met, and the sheer joy of effort, the challenges, and the learning I gained.