Spitfire

My father’s medium, the element wherein he came alive was air. His passion was flying. His achieved rank in the Royal Canadian Air Force was flight lieutenant, equivalent to captain or lieutenant in contemporary armed forces terminology. My dad never knew or met his father, Lorance Thomas Morrow because my grandfather enlisted in the army, fought, and was killed in the First World War in 1917 never making it home to see his new-born son. In turn, my dad enlisted with the RCAF sometime after the outbreak of World War Two. My father would have been in his mid-20s when he enlisted and subsequently fought in the War, a fact very hard to understand and fathom for me now. Did he feel this was his patriotic duty? Was he afraid? Did he think about killing people? Did he kill people? What was it like to be a fighter pilot? He never spoke to me or answered my questions about what he did as a fighter pilot flying Spitfire aircraft during the War. My assumption is the plane in the picture above is a training jet either for him or for training pilots, the latter his passion. Also I would guess this photo was taken sometime in the early- to mid-1950s, judging by his age and body-type in the picture. While I am still in possession all of his flight-plan/record logbooks, they only list unspecific information, very sparse information particularly during the War years.

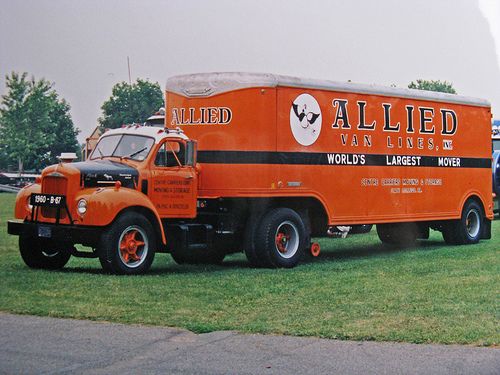

What I do remember is growing up air force. Living in rented homes or PMQs, private married quarters or military housing. My dad going to ‘the mess’ to eat with the boys, his chums. Being aware of search-light beams emanating from air traffic control towers and guiding flyers home at night. Going to air shows – once, when I was around age 7, my dad took me up in a Spitfire or Harvard aircraft, I think, and did loops and other aerobatics, scaring me speechless and to tears. Wearing old flight helmets to play mock-air force games with my friends. Moving to a new ‘post’ every three years, a fact of life I assumed was true for everyone – some friends left in year 1 of our posting, others in year 2, and then we moved at the end of year 3- as we packed our belongings into huge boxes – the very large wardrobe boxes were my absolute favourite ones for using as forts – to be carried by orange, Allied moving vans:

Vividly I still think about making parachutes out of my dad’s handkerchiefs by tying strings to each corner, weighting the open string-ends with some piece of metal or stones then throwing the folded ‘chute to watch it descend somewhat more gently to earth than normal. Seeing my dad’s winter (khaki) and summer (blue) – or the other way around – uniform shirts, impeccably ironed and hanging in his closet. Making model airplanes out of balsa wood or gluing plastic kit pieces together and hanging those models by threads tacked to my bedroom ceiling. Realizing his wings emblem on his air force jackets and hat was special – he had literally earned his wings to fly. Below are 3 images of restored spitfires in flight:

Above, a banked turn, I suspect . . .Spitfires could achieve 350-400 mph top speeds – or 325 knots (nautical miles related to the earth’s degree of latitudes) – and an altitude ceiling of 30,000 feet (just over 5 miles high)

Above, what must have seemed tranquil flying over a rural landscape

Above, more likely how my father would love to fly acrobatically

Inside the cockpit of a Spitfire – home, I suspect, to my flying father; the seat was framed to encase the pilot’s parachute on which he sat with its straps suspended over his shoulders

And the cockpit of a Harvard aircraft, also a home to my dad. I marvel at the aviation skills me must have achieved in all the cockpits he knew

My father suffered a major heart attack at mid-life (41 or 42 years of age), quite literally and very likely a broken heart after my mother died. Faced with the prospect of finishing his career at a desk job, no longer permitted to fly, he chose retirement from the RCAF and returned to his pre-military career selling general insurance, wearing civies as he would call non-military garb. I imagine now that his decision to leave the air force was gut-wrenching. To this day, every time I come to sit on a passenger airliner, I think my dad understood how to fly this craft or at least the mechanisms and skill sets involved in flying such a plane. In fact, I remember quite clearly him teaching me how air currents – he actully used the term, bernoulli’s principle in conveying this to me – affected the lift on airplane wings. He would blow over the top of his hand-held piece of paper resulting in the unheld side of the paper rising upward as a plane would do. Nothing he did, not his physics of flying lessons or aerobatics ever inspired me to follow his air force career although I did try air cadets, briefly, in grade nine but just didn’t enjoy the rigors of what seemed like endless periods standing at attention in uniform for inspection.

I think of his skill, his years of teaching young pilots to fly, to soar, to experience and be competent at the activity he loved. In the 1950s, I remember him travelling to air force bases, mostly out west – Gimli, Edmonton, Saskatoon – to teach at flight schools. After evert stint, he brought my two sisters and I something as a gift when we welcomed him home; I still have a gyroscope and its perch of a mini Eiffel tower he gave me after one of his sojourns:

By placing the long axis end of the gyroscope on the top slot of the tower and then carefully pulling a string attached to the centre disk of the gyroscope, it could be made to spin around its horizontal axis while perfectly balanced on the tower. It absolutely fascinated me. What I did acquire from my father was his love of teaching. Even in everyday life, he had a way of instilling learning for things like household safety – always unplug the toaster before trying to extract a stuck piece of toast; never carry a knife of any kind, blade-up – explaining math calculations, and how to treat others (he devoured Dale Carnegie’s leadership training books like How to Win Friends and Influence People, a copy of which stood in the top shelf of our family’s glass-door book case for years).

What I remember most about my father’s penchant for flight and flying is a story he told us, probably after he retired. More than anything, this story typifies my dad’s joie de vivre, his impishness, his sense of humour, and how I re-member him. Just after he earned his wings, he was stationed in Aylmer, Ontario. He decided he wanted to show off his solo skills to his mother who lived in the nearby town of Simcoe. To get her attention, he did a very low, fly-by near her house. Whether or not she ever saw him, I don’t recall; however, during this stunt, he scared a horse tethered to a milk-delivery wagon and the horse bolted. No one was hurt but my dad was reprimanded. I don’t know how many times I heard him tell about this adventure and every time he did, he laughed hard enough to bring tears to his eyes. There was a ‘spitfire’ component, in the emotional sense of that term, to my father’s personality and character. Perhaps in tribute to him, all my life I have kept this piece of furniture, my “airplane dresser:”

Today, this dresser sits proudly (oh yes, a dresser can be proud …. if anthropomorphized properly) in my/our tool room, its small drawers housing various items like sandpaper, electrical cords…all manner of household items. As far as I know, this was my first dresser as a very young boy and it is untouched by refinishing…just sans one front right let. The coloured, stylized airplane always reminds me of my dad and I have always called it my airplane dresser.

Watching this video about the spitfire, I marvel at the aircraft and my dad’s skills and I tumble home to the memories of my father the flyer and his pilot-passion for his sky-time.