run, … Boston

… more than 40 years have passed since my first Boston marathon in 1978. Learning to run, doing something so elemental, challenging, peace-enhancing, quiet, and just so very physical has been a joy and a privilege for which I give thanks every day. This blog stems from a piece I did a few years ago. The events leading up to that Boston and my lifelong passion in being a runner are imprinted within me as though it were yesterday…

Running, in my early life, had always been a means to an end – the fastest way to track down a squash ball or a badminton shuttlecock or to get underneath a quarterback’s pass in high school. The 12-minute run – Cooper’s biggest aerobic hoax (his 1968 bestseller, Aerobics) played on an unsuspecting public – always lasted at least 2 perceived hours and left me in paroxysms of hyperventilation and pantomimes of fatigue in high school and university. Running was a chore. When I ballooned more than 30 pounds starting graduate work, something there was that whispered to me, ‘run now,’ no less audibly than the Marabar Caves whispered ‘Esmiss Esmoor’ to Mrs Moore in E.M. Forster’s celebrated A Passage to India. There was no rhyme or reason to the allure just the unbridled logic of the felt need to burn calories and once accomplished, I assumed, running could be easily jettisoned from my life.

In the early 1970s, specialized running shoes were not easy to acquire. Converse All-Stars were my prized possession ever since being given a pair when I made my high school basketball team; they would suffice as thick-soled, canvassed cushions against the cold Canadian clime. Running, I surmised, couldn’t be any different than learning to walk – just a faster series of near-accidents, narrowly avoided. Up on the balls of the feet, long strides, high-knee lifts…who needed lessons to run? Starting at a few blocks, increasing the distance exponentially – at 22 years of age, every new progression seemed to be a steep function – running became a daily ritual. In combination with the grapefruit diet popular at the time, pounds came off quickly, clothes fit better, sleep was easier, squash games were won more frequently, and the means-to-an-end became a process, time to go inward – I found I could think and run, be physically and mentally acute at the same time, who knew. In that first year, running became a feeling, often a yearning for the next run, and very rapidly, less an activity to complete or endure.

By the mid-1970s, I thought I was pretty good at this new hobby. Running was a companion to me, a fluidity of my daily life. 5-mile (now 8 km) runs were my norm and I even spent a small fortune in sending money to Helsinki to buy state-of-the-art Karhu, Finnish running shoes – a set of ordinary trainers and a pair of luminous, orange racing flats that weighed less than an ounce. Nike Cortez shoes were available in my home town but the Finnish shoes were prized, even weighed and ogled at by two of my colleagues, both of whom were superb distance runners. All the sun long I was running (Dylan Thomas’ Fern Hill’s verses of unfettered joy often rang in my inner ear on the roads).

And there was a curious, quiet, even abnormal appeal to long distance running in that runners were relative rarities on the roads, often the object of drivers’ inadvertent attention or even derision for taking up space on their, the drivers’ roads. Careless motorists making right hand turns out of streets or parking lots often, it seemed, looked left but only to their right occasionally, if at all, before beginning their turn. Wary runners cursed them and shared their best stories of payback. Dave, one of my fellow runners, ill-tempered likely from carrying a full time job while being enrolled in an almost full-time professional degree program, raising a family, and trying to maintain his marathon racing interests, had experienced too many close calls out on his long runs. As he started out on one of his training runs, a driver did the right-hand turn, no- look maneuver; Dave deftly skirted the right-rear bumper and with an open, flat-hand, smacked the back of the vehicle, then quickly lowered himself prostrate on the ground behind the car, feigning unconsciousness. The startled driver braked the car and bolted out her door and scuttled toward him, hands on her cheeks in abject shock at what clearly she had done. After a long few seconds, Dave turned over, pointed his finger at her and said, ‘Never again!…look both ways!’ Very likely, she never forgot.

Dave-running stories were near legendary; local, locker-room lore was such that he reputedly went through the back doors of a taxi sedan whose cabbie had stopped his vehicle directly across the pedestrian-designated walkway at a traffic light. Dave deftly opened one door, crawled through the unoccupied back seat, scowled at the driver and exited the other rear door. Once, impatient at being forced to wait to cross the railway tracks because of a slow, shunting train, Dave actually rolled under one of the moving cars to get to the other side and continue his run.

Coming back from a run at work one day, engrossed in my pace, doing my finishing kick in the last half mile, one of my colleagues, Jerry, running in the other direction on the other side of the street made a derisive comment about my ball-of-the-feet, kind of tippy-toe running style and concomitant hang time between steps. That comment from Jerry, as much as it stung at the time, was the beginning of some 25 years of learning about and thrilling to run long distances. I became a running disciple to this University of Michigan former miler and apparent fountain of long distance running wisdom. The whispered ‘run now’ from my earliest lose-weight running experience morphed into ‘run better’ and I soaked up Jerry’s advice like a human sponge as though my instinct knew running could mean so much more than just running. What does he know of running, who only running knows, with apologies to C.L.R James and his famous quotation about cricket.

Emboldened with a subscription to Runner’s World and having read Sillitoe’s, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner 1962 classic story some years ago, I sought out my own ‘loneliness,’ less lonely than the word might imply and more the solo privilege and feeling of running long distances, the process of each run. There is a huge difference, in my view, between being lonely and being alone. Many are those who have asked me, as people often ask runners: ‘What do you think about on those long runs?’ ‘Why do you run?’ ‘Why do you run so far?’ ‘Aren’t you always tired?’ ‘How do you sweat that much?’ Three words from Johnson’s poem Grabbling became the my stock reply, some variation of, ‘Get wet Boy’ – just do it – in later years. Comparably, I remember a friend of mine at the Squash Club where I play who, when I asked why he drove a Corvette, responded with, “have you driven one?” No, was my reply, and he said, “then I can’t tell you why.”

Jerry taught me the seemingly most bizarre truism of running – all running begins with the thumbs. Arms, he said dictate how your feet move and how you hold your hips and torso quiet and still. As one thumb goes forward, forearm parallel to the ground and driven fully in the direction of the run, the opposite knee goes in concert with the thumb. Pace then, is set by the thumbs; simple bio-mechanics of efficiency. Sprinters, Jerry noted, ran on the balls of their feet but sprinting is not long distance running; in the latter, you land softly on one heel, roll forward onto the outer edge of that foot and then plant your foot to coil inwardly, crescent-like over the whole ball of the foot and push off on that part of the foot to complete the stride under the great toe. Length of stride was not the issue, rather the rapidity of foot turn-over from the front to the back foot was the distance runner’s gait-quest. The logic was easy, and it was hard, initially, for me to break my racket court, burst-running habits and yet my body felt the insightful lesson’s rightness. Running downhill, lean your hips forward, let the hill do the work; running uphill, envision a plumb-bob traversing your torso from between your hips to the tip of your head – do your work with the hill, not against it – more gems from Jerry.

As the 1970s decade progressed, so did my allure to running. Turns out that although one exercise physiologist told me never to run after that expert forced me to endure one of the terrible, 12-minute trials in my pre-running addiction days, I did have a genetic gift (I chose my parents wisely), an extremely high maximum oxygen uptake (VO2, in exercise physiology terminology), a rare aerobic ability to take up and utilize oxygen very efficiently over long periods of time. This high VO2 was laboratory-determined when I was coerced by my exercise physiologist colleagues to run on a treadmill – I loathe treadmill running, to this day – while they monitored my heart rate and gathered several Douglas bags of exhaled carbon dioxide, the latter to use in calculating VO2. Buoyed by the gradual integration of Jerry’s bio-mechanical advice and affirmed by my body’s innate oxygen-processing capacity, I ran my first 5-mile race. Zealous to do well, I went out way too fast and learned my first race-running lesson in lactic acid pain. But it was the aftermath of the race when both Dave and Jerry smirked at me and proffered that the 5-miler would lead me to 10-milers and then to half-marathons and then to an actual marathon. I scoffed at their predictions, just not on my radar, if I even had a vision for this running life beyond the daily joy of running for its own sake. And yet there was a seer-like truth to the tentacled embrace with which long-distance running seems to envelope its devotees and I was no exception.

By 1976, I found I could do 10 miles easily in just under 60 minutes and the lure of completing a marathon drew me omnivorously to become the center of my daily universe, my escalating preoccupation with 26.2 miles knew no boundaries. I was aware that Jerry annually ran the Boston Marathon – that vowel-laden, ethereal mecca-race that drew real runners on the third Monday of every April, Patriots’ Day. And proudly, I also knew that the Hamilton, Ontario, Around-the-Bay road race was 3-4 years older than Boston, from an era when the term ‘marathon’ could be applied to almost any long-distance race of about 20 miles. I was also cognizant of the fact that Jerry ramped up his normal, daily runs toward his Boston training some 8 or 9 weeks before the marathon. Running Boston, meant you had to qualify by running an age-appropriate, qualifying time in another marathon. So be it, I thought, and I invited myself into the Sunday-morning marathon training group that Jerry lead annually starting in late January or early February. The plan was obvious – qualify in some less renowned marathon and then do the Boston.

Hard as the mid-winter training was, I devoted my time and energy to the rigors of running 18-23 mile runs on Sundays and 8-10 miles daily during the week, Saturdays off to rest up for Sunday’s big run. Jerry’s view was ‘you don’t leave your race on the road,’ so never do the full marathon distance. Instead, he said, teach your body to stay on your feet running much longer, albeit slower than your planned marathon time. All made sense and that first marathon-training, 2-month period seemed to crawl by; it was painful and I felt always on the edge of physical fatigue, at times sparked only by my overwhelming zeal to do Boston. I had to qualify within one year of any Boston-year; I chose the newly-created Ottawa marathon in late May, anticipating the Boston in the next calendar year.

Completing my first marathon and qualifying was a success but not without its share of teaching and learning. I would be shod in my new Brooks’ shoes and clad in white Adidas’ shorts with 3 red, obviously racing stripes on each side. Two nights before the marathon, I got food poisoning – not in the pages of Jerry’s running book. A druggist recommended enterovioform tablets, designed to quell what the pharmacist called loose bowel motion. Dehydration, I knew, was absolutely anathema to runners so I saturated myself with water over the two days before the event. Came race day, a bright, blue May-sky morning in Ottawa and the ‘motion’ was quiet; just in case, I put two of the beige tablets in a small plastic wrap and pinned it inside the front waist band of my pocket-less, Adidas’ shorts, along with two extra Carefree gum sticks. Confident I could hold pace, I smirked on the starting line recalling Jerry’s 2 pieces of last minute marathon running advice: 1) “look like a brook trout” at the start because if you don’t, you will carry that dejected visage during the last 5 miles when the finishing, agony-struggle of a marathon begins; and 2) his antithetical refrain to a consistent, planned, and sound race pace, “go out hard, pick it up in the middle, and kick at the end.” The race was an out-and-back route, starting at Carleton University, north toward downtown Ottawa, then west along the full length of The Parkway, turn around at its end, and re-trace the course back to Carleton.

All went well; astutely, I planned my race and raced my plan, kept on a steady, comfortable pace. A minor, but very painful hamstring cramp hit me at about 16 miles but I worked through it and got back to pace and that cocky, feel-good, I’ve-got-this- one-easily illusory state of mind. At 21 miles, just near the federal Parliament buildings, two runners came up beside me; one of them had run with me earlier in the marathon but had left the race-course to use a toilet. That runner asked the me directly how I was doing and kept on asking me similar questions. Taken aback by the ongoing questions, I asked why he was so curious about how I was doing. He replied, ‘Well, I’m concerned…you seem to have shit yourself.’ I looked down and sure enough, my white shorts were tinged brown throughout the crotch area. All I could think about was how much I must be dehydrated and didn’t even know I had evacuated myself. Should I stop, get help, where would I get help, how could I not have felt anything? From some mental recess, I remembered the enterovioform pills and reached inside the waist-band for the tablets in an effort to at least do something in self-care. There were none, the sweat-dampened cellophane wrap had opened and the two brown tablets had absorbed themselves into the sweat of my shorts thereby creating the now-embarrassing legacy of crotch-stained apparel directly in front of my nation’s seat of government. Relieved, but not literally, the enterovioform-story became one of my favourite running adventure experiences to share on long training runs in later years. More to the only salient point, I qualified for the next year’s Boston.

All I knew about “Bean town” was derived from the city’s sporting events – the famed Red Sox with Fenway Park’s Green Monster wall and Eddie Shore’s and Bobby Orr’s Bruins in the NHL – and some vague memories of learning to recite parts of Longfellow’s poem, Paul Revere’s Ride. In the weeks before my Boston-qualifying marathon, I went to Boston to experience the race, sort of second-hand. It was 1977, the year Canadian Jerome Drayton – his name of origin was actually Peter Buniak but he adopted two other famous runners’ names – won the marathon, a clear sign that I too could do Boston. The feeling of observing the race for me was that of voyeur or being in athletic stasis like one of Tait McKenzie’s renowned sport sculptures whose figures were always caught in moments neither involved or uninvolved in their event. Watching long-distance runners run felt contradictory; there was no way to join the run or feel part of it for me until I was one of them. What this spectatorial Boston marathon debut did do was harden my resolve to qualify a few weeks later, though unknowingly, enterovioform embarrassment and all.

An eternity passed until Boston training build-up began the following Winter. The running group always met early on Sunday mornings at Jerry’s house located in the subdivision of Sherwood Forest, Robin Hood’s hood, I joked. In pre-water-belt days, group members either hid Mason jars of water at strategic points along the routes the night before or they were hydrated by the kindness of Terry, my good friend (pictured in the Watford Road Race image above) who met us every 5 miles or so with fresh water. Getting accustomed to running with water in the belly was essential and drinking water before a run or race as well as forcing water into the body was vital to long- distance running to avoid dehydration and/or cramping.

Weekly long-runs built from 13 miles – “just to get a feel for how much work had to be done ,” said Jerry – to the longest, 22 miles about 3 weeks before race-day. For me, those Sunday runs were the essence of long-distance running and training. I could see and feel my body transform into litheness. I learned pace and in the longer runs I experienced the threshold of when fun left the run, when the early run chatter and stories became silent and the footfalls, occasional spitting, farting, and nasal-clearing became the dominant sounds of what that year’s book-released running hymn, Parker’s Once A Runner coined as the trial of miles and the miles of trials. Long distance runners are each an experiment of one, according to the then-running aficionado, George Sheehan who coined the phrase in his talks and books on the process of running.

Between Sunday runs, Wednesdays were truly hump-days, the hardest runs of the week mentally, usually 10 milers, often at slightly faster than anticipated race pace. Speed work to me was a lesson in awe and humility. Jerry taught me how to fartlek, to speed-play or run very hard for the distance between, for example, two telephone polls, then slow the pace for 3 or 4 sets of polls, then repeat the faster intervals. These once or twice a week speed-spurts hurt; my quadriceps ached for days. And yet the almost joined-at-the-hip sense of lowering my torso and centre of gravity into the ground and committing to speed with Jerry was a kind of corporal, mutual respect in fast-paced synchronicity. The voice of experience in Jerry said these fartleks were money-in-the-bank, a reserve from which to draw during the actual race. And the last two to three weeks before Boston were tapering ones with gradual decreases in both weekly mileage and Sunday run distances. About 8 days before the race, I tried the contemporary wisdom of carbohydrate depletion, protein-enriched diet for 4 days followed by 3 days of carbs’ loading with no running. While never attaining the vaunted runners’ endorphin-induced high, I did experience a vivid, alluring desire to run under a passing school bus 3 days into the carbs’ depletion phase, a craving some part of my apparently high-jacked amygdala told me ought not to be indulged.

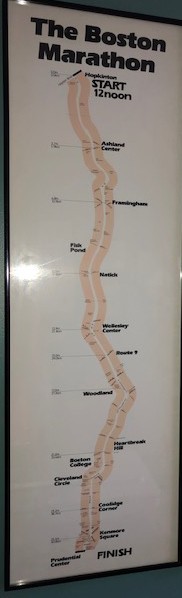

Hopkinton, Massachusetts, the little town where the Boston began, was a carefully measured 26.2 miles from the Prudential Center. The difference between and among the Boston Marathon and any other marathon was and is the experience of running the race and its traditions. To run Boston mindfully is to run its history and engage in an event where every physical and mental and emotional fibre is tested and re-tested by an unrelenting and unforgiving course populated along its length by more than one-and-a-half million people who come out to cheer the runners in their yearly, Spring pilgrimage in and homage to running. Hopkinton was woefully unequipped for the arrival of some 12,000 runners, most officially qualified, some not, who descended on the little town by school-bus loads beginning at 6:30 AM the morning of the scheduled high-noon starting time. Bags of post-race clothing were left at the finish line and the issue became what to wear during the hours before the marathon start. Jerry advised old-clothing, the last of which could be doffed at the starting line or early in the race; in case of rain and/or wind, bring a garbage bag, pierced with a head-hole and two arm holes at the bottom of the bag such that it could be worn upside-down for warmth and rain protection.

The feeling for me in Hopkinton was more of being bloated than pre-race jitters. I had not run in 4 or 5 days and my body yearned so fiercely to move. Eating carbs in the days leading up to the race super-saturated my muscle and other cells with water, crucial to surviving both “halves” of the race, the first 20 miles and especially the last 6. Hydrating in the morning was forced and it had the obvious effect on the thousands who needed to use the portable toilets or more likely the woods surrounding the public school grounds where most of the runners congregated. One of my most enduring, strangely so, memories of that Boston was one from, of all things, a urinating event in the Hopkinton woods. The line-ups to the toilets were long and the obvious choice, at times the most pressing need was to find a tree and pee. On one such bladder-relieving occasion, I, generally going about my own business but fully aware of hundreds of others in the open woods, noticed a young woman entering the area. It was only 7 years since women had been allowed officially to run the Boston and men far outnumbered women. Nevertheless, entering the arboreal lavatory area came said young woman, the only female, it seemed, in the woods. What would she do among a forest of men and how would she do it, I wondered. Some 200 yards away, with her back to the school and to me, she squatted on one knee, stuck her other leg straight out from her hip, pulled her shorts aside at the crotch and peed! It was a revelation, an unanticipated moment of another creative athletic stasis, strange as the incident and its impact on me may have been. Crotches then seemed to punctuate my first two marathoning experiences.

And the Karma of my forested semi-voyeurism, I knew, could be a bitch. Runners ambled to the starting line starting about 11:30. Small signs identified sections where runners could organize themselves, on the honour system, by qualifying times, each area separated by ropes set up at intervals across the road. Runners at the very back of the thousands amassed behind the starting line would be several minutes before they actually began to move. As the last minutes ticked away toward noon, the ropes were dropped and the throng collapsed into each other, accordion-like, in a natural quest to get closer to the starting line. Crammed and surrounded by other runners, mild retribution struck when someone urinated on my leg, the offender unidentifiable in the crowded conditions but the result stored in one now very-damp sock.

The early miles were ones of pre-race release, even surrounded literally by hundreds of runners; finding space and pace to run seemed easy. Jerry and most of the other runners from his training group were ahead of me and I knew enough about the course to run within myself, acutely aware of other runners but more listening to my own body, my own running rhythm. The day before, I strolled Boston Commons and watched in amusement when a seemingly dormant man sprung up from behind Paul Revere’s headstone in the Granary’s graveyard and chanted the whole Longfellow poem before resuming his prostrate posture. Shortly after that recitation-event, I drove with my friends along the entire Boston course, just to see it as though doing so would give some advantage. For most of that drive, we were situated behind a group of Japanese men in a large, perhaps 3/4 ton truck. The men, runners or maybe runners’ coaches, were filming the road with video cameras, intent on capturing its contours backwards, all 26 miles of them, I assumed, to learn the nuances of the running route.

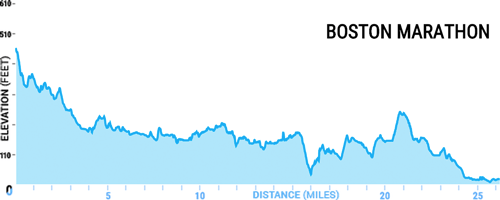

What I knew about the Boston marathon, I committed to memory from conversations on the long Sunday runs. What distinguished the actual race course from most, if not all other marathon routes was the fact that the Boston was 17 miles of slight downhill, followed by 4 miles of hills and plateaus between the hills, and then 5 miles of slightly steeper declinations to the finish line. To run Boston was to run with control and with respect for its terrain, especially the undulations; the idea was not about finishing – the survival shuffle in the last few miles of long Sunday runs were about accustomizing the body, and especially the mind to the demands of physical endurance – but the race was about thrival, I knew, and that meant running within one’s own limits. PBs or personal bests were not likely to happen at Boston, at least not for 98% of its devotees.

By the time I came into Ashland, 4 miles into the race, I could feel myself sweating, could swimmers ever feel that, I wondered bemusedly. More significantly, I could sense the run in my core. The wind quartered into the pack providing an ideal, natural coolant and my stride was gentle, anticipating and reflecting with each step my 6:50 per mile pace for a planned, just-under 3-hour finishing time. Ashland, I remembered, had once been the start for the race, pre-1920s when a marathon was any long race of about 20 miles. Some years after the 1908 London Olympic marathon race when the starting line had been pushed back 4+ miles to enable the royal family to witness the event’s start, the marathon distance became the now-conventional 26.2 miles – God Save the King or Queen indeed, I thought, with 22 miles to go.

The legendary, eccentric Australian athletics’ coach, Percy Cerutty reportedly opined that anyone could run 20 miles, but not everyone could run 26 miles. And as Cerutty’s marathon aphorism came to mind, I pictured the eccentric coach leading his bare-foot running charges up the Outback’s sand dunes on their training runs. Heading out of the town, it seemed minutes of time rolled through my imagination about Ethiopia’s marathon runner nonpareil, Abebe Bikila, he who ran races in his bare feet, even in winning the 1960 Rome Olympic marathon over the cobbled streets of that ancient city. I gave a silent tribute to my Brooks’ runners cushioning each heel-toe step buffered too by my favourite Thorlo socks, they who never slid down or bunched or, in their double thickness, were less likely to create blisters even with one dampened sock.

Framingham, the next town, seemed to come up quickly, one long stretch of buildings at around 7 miles. I recollected the data from the well-known Framingham heart studies and pondered what I thought I knew from their longitudinal results about heart health, physical activity, diet, and other lifestyle factors that were only beginning to be studied. Strangely, it occurred to me, at just under a third of the way through the marathon, that training for and running marathons was unquestionably unhealthy. For some, it was an obsession – I could admit, uneasily, to that fact too – for others, a personal quest for athletic achievement, aerobic fitness, and just an endurance contest. As primed as my body could be to run 26.2 miles, it was an absurd goal, always with my body on the edge of ill health. Injuries from over-training loomed precariously and often, over the years, landed with a semi-debilitating thud – bouts of neuromas; dropped metatarsal arches; plantar fasciitis (I would wake up and crawl to the bathroom to avoid putting pressure on the arch of my foot); iliotibial-band syndrome; and ‘blackened’ toenails wrought by jamming the nail-bed of unsuspecting toes on the inside toe-boxes of running shoes.

Mentally, in the 8-week build-up, every aspect of daily life was funneled toward training, all other life activities, except eating, were a distant second. Marathon racing was a preoccupation that became all-but an occupation in terms of time and attention. Running through Framingham felt like coursing through the literature on physically active lifestyles – Cooper’s 10-year old tome now a classic in the literature and the United Kingdom-based studies on bus-drivers versus conductors, mail carriers versus mail sorters, and the Type A versus Type B research on personalities and cardiovascular issues – all seemed to coalesce in my mind’s eye as I headed straight out of town toward Fisk Pond.

At Natick, I completed 10.5 miles, an easy day’s workout distance back home. Sweat now soaked my navy blue t-shirt and my nylon shorts wicked water to my feet. Vaseline applied to the inside of my thighs was an important preventive measure against the long distance runners’ bane of friction induced ‘crotch-rot.’ 10 miles; check in with yourself Jerry said, see what you’re feeling. Will this race come easy or will you have to work for it, every step an effort. For me, nothing was sore and though completely in silence against the din of other runners, I felt in a kind of cocoon of comfort, a knowing-ness that it was not about finishing; it was indeed about the proverbial, one racing-step at a time. And, Jerry had also said on the previous day’s drive over the course, when you get to Natick, don’t forget Tarzan Brown.

Stories and sayings and running lore came out of Jerry like exhumations from a cornucopia of treasured truths, or half-truths, I rarely knew the difference. Never quiet on a training run, Jerry seemed comfortable with almost any topic but sports were the focus of his storytelling best and marathon stories were the top gun of his lexicon. Inept, in his view, NCAA basketball coaches didn’t know if the ball were stuffed or pumped, he lathered. Ice hockey was a slippery surface sport; light rains happened to keep the dust off baseball infields; and rowers were the only athletes praised for racing backwards. When running became too easily media-linked to deaths from over-training (more likely from pre-existing heart or other health issues), Jerry made his charges promise something to him. Blessed with a self-professed million-dollar body but a five-cent neural system that impacted his cardiac rhythm, he told his fellow runners that if they were ever with him and he keeled over while on a run, they were to find a tennis racket and stick it in his hand before they called an ambulance – this he said would buttress him from any claim that running killed him.

Jerry, this ancient marathoner held his fellow runners spell-bound with two rhyme-stories and I was to hear them at least a score of times over the next two decades. One was about the building of a ‘clunge,’ a fictitious structure that required half the US armed forces and most of the world’s intelligence services’ expertise and assistance, and Jerry could string its narrative for miles just to alleviate the tedium and mental fatigue during a hot-day’s long run. The second one I smirked inwardly about as I pulled into Natick – Ode to a Toad Who Lay Dying in the Road, Jer’s saga about a poor toad, told in perfect rhyming couplets while running the last few miles of a Sunday run, to remind his charges about mental toughness. Don’t get caught by the bus, he said, in reference to giving up in a marathon. Or, don’t let the bear get you at 21 miles, that anaerobic threshold crossing-point – the start of the second “half” of a marathoon – where the marathoner’s body switches from carbohydrate fuel to fat metabolism and the feeling often is like you are shouldering an extra weight, about that of a grown bear

But it was the Tarzan Brown narrative of the incomparable Native American marathoner from Rhode Island who excelled at long-distance running that occupied the images in my mind as I moved through Natick. Tarzan was not merely fast, he was unconventional, unpredictable, and a legend on the Boston course. He had won the event twice in the 1930s and seemed to be invincible. In 1945, he decided to make a comeback, was among the 4-person lead pack coming into Natick when, according to Jerry, for no apparent reason at all, he jumped the fence and dove into the lake, as if in tribute to his contemporary, Johnny Weismuller, the jungle-Tarzan of Hollywood fame. Tarzan Brown just smiled and waved as he bobbed up and stayed in the lake, never resuming his race. Some say the event never happened or that it took place much later in the race, perhaps in the Charles river. Nevertheless, Tarzan was a raw runner and I think that’s why Jerry respected him and this lake-story, and he wanted all runners to remember Tarzan as they ran through Natick. To run Boston attentively – mindfully, in the current vernacular – is to re- experience its folklore.

Over the next couple of miles, I started to think about coming up to the half-way mark of the marathon. I remembered my own favourite Boston marathon story, a kind of mirror image, in time, of the Tarzan one. Canadian Bruce Kidd was a world- class middle distance runner in the 1960s. Bruce once told me that the only marathon he ever ran was Boston. Never qualifying, he was invited to the event because of his running prowess. The Boston has been run in sweltering heat (over 114 degrees in the early 1970s) but for Bruce, his Boston was bitterly cold and there was very little fat on his honed, running frame. At the time, in the mid-1960s, spectators could drive along one side of the highway because there were not nearly as many runners. Bruce, in the lead pack, similar to Tarzan’s 1945 run, somewhere around the mid-point of the marathon, was freezing from the light rain and wind. As some of his friends drove alongside Bruce, one asked how he was doing, and jokingly inquired if he wanted a ride. Bruce said he just couldn’t imagine anything more alluring than that warm car so he got in the back seat and never ran anything approaching the marathon distance again.

As I began to feel the weight of almost 90 minutes of running, my quads started to ‘talk’ to me from the imperceptible downhill topography, and then the much-vaunted noises of Wellesley reached my ears. Jerry told us about the Wellesley College girls but I had assumed it was a Clunge or one of his Toad tales. And yet, as the College building came into view, the spectators, about 4-6 people in depth on both sides of the highway seemed to converge toward the loudest-sounding part of the road. Directly across from the College, the Wellesley girls, some draped from College windows and many lining both sides of the street, screamed as the runners were funneled through them with no more space between them than for two runners side-by-side. Tradition and experience said if you wanted to slow down enough, one or more of the girls would kiss your cheek, a feat which in most cases would seem to be less than alluring given sweaty bodies and the need to slow down to receive the peck. How could I not, I thought to myself – what would I tell Jerry if I didn’t. Whether I actually accomplished this embrace or not, I perceived I had and I grinned, very likely the only grin of any proportion until long after I finished this race.

In reality, the Boston Marathon begins shortly after Wellesley, the adrenaline high of the College greeting now subsided, the course veers left around the Newton-Wellesley hospital grounds at about 16 and a half miles. Mentally, I knew what was coming and for some curious reason, it seemed like walking for a while was a good thing to do and so, I did. I even thought, ‘I could go into the hospital, they would help me.’ And I realized, there was nothing wrong; I had committed to the race and stopping just wasn’t an option. The fleeting respite of rest ended with some Samaritan offering me ice-water and soft words of encouragement

The hills of Newton loomed. I knew the hill synonymous with Boston, Heartbreak Hill, notorious for purportedly bringing runners to their psychological knees, was the third of four hills, not the last one, as some runners believed, very likely adding to their heartbreak when they hit Chestnut Hill, the fourth one. Heading into the first hill just after mile 17, heeding the plumb-bob body posture wisdom, I actually felt relief in running uphill after so many miles of slight, but constant braking on the downhill course. Part way up that hill, I saw an orange-lettered sign, neon perhaps, I couldn’t tell, that gave the time of the top 3 male runners at that point of the course. I did the math and realized in absolute amazement that the lead runners were hovering just under a 5-minute per mile pace or close to 2 minutes per mile faster than I was running. Clearly, I mused, they chose their parents wisely.

I pushed through the first three hills admiring the splendor of the homes in the Newton area. Crowds were thick, 10 or more on each side of the road some of them telling runners just how ‘good’ they looked (a sure sign to runners that one was actually looking anything but ‘good’) and lying in understating, albeit with good intentions, about how far they had to go to the finish line. As I started up Heartbreak Hill, I grabbed two cups of water, one I poured over my head and neck, then my thighs and the other to drink. As I tossed the paper cups, there was a spectator with a hand-crafted sign that showed a steep hill personified with its tongue sticking out. Was it a derisive, heartbreak-hill mocking runners or was it a tribute to our tenacity and achievement? Did it matter unless runners made it matter? Reaching the top, I graciously accepted the cheers as one male runner slid past me just at the crest of the hill. I noticed the passing runner because he wore a full buffalo head piece, thick with black fur, about 18 inches high, complete with horns. A sign on the runner’s back said, ‘Save Lake Tahoe.’ I didn’t know what part of the lake needed saving but I couldn’t help but wonder if the runner had worn that top the whole distance and if so, how he had sacrificed the area of his body that dissipated the most heat, the top of the head.

Right on cue and lifting my spirit after the hills, I spied the giant Citgo emblem as I crested Chestnut Hill. It was much more than commercial; it was literally a foreshadowing sign. Jer had told all of us, when you first see the Citgo logo, you are exactly 5 miles from the finish line. And in the same breath, he reminded our group, not to let down our commitment to finishing; never, he said, finish the race before it’s done. It was a flash of realization; 80% of the run was done and, mentally and physically, it was the start of the last half of the marathon. More pressing than heeding Jer’s advice or celebrating the Citgo sign, was the very strong aching in my quads as I rounded Cleveland Circle over the cobble-stoned street. It felt as though an ethereal Voodoo practitioner was gleefully stabbing my thighs with ice-picks. There seemed to be just no give to my cement-like thigh muscles.

Distinctively, perhaps in a distractive effort, I vividly remembered my third-year physiology lecture content on the sliding filament theory of muscle contraction. The principle held that the two protein elements in muscle, myosin and actin, were neurally activated to twitch in contraction and actually slide across each other, in effect, alternately shortening and lengthening the muscle fibers to do work. I also knew that genetically, each person has a certain proportion of fast twitch and slow twitch muscle fibers. Presumably, sprinters had more of the former, marathoners more of the slow twitch. What I fathomed clearly was neither physiology or genetics could help me now; my filaments seemed to have abandoned both the theory and sliding/contracting practice. I knew I was likely experiencing some degree of dehydration, lactic acid build-up in my thigh muscles, the workhorses of all running events, along with the worst of marathon’s enemies, mental fatigue. The longing was to drink large quantities of water and to walk; water was still important but at this stage, no amount of water, I realized would slake either my thirst or relieve my quads and walking would just breed more walking.

Without question I knew I was now metabolizing fat and I also realized I had trained for this thigh-ache feeling by running long downhills in training runs and by running miles 10-15 of the 20 mile runs in a minute-per-mile faster than anticipated race pace for that 5-mile interval. My mental faculties, diminished as they were, knew what my body wanted to deny, simply this, I had the capability to keep running even though everything in my head told me I needed to quit. Fellow runners by the scores were walking; some just sat down and wept, white-salt stains on their t-shirts and some of the men with ‘number elevens,’ 2 parallel, thin strips of blood running down their tops from sweat-induced nipple abrasions. It seemed like it took forever to recommit to the race, to self-talk my way along Commonwealth Avenue, its tree-lined center park offering shade that was out of reach. The crowd was screaming; police on horseback steed-rumped spectators back in effect buffering runners from collisions. And somewhere I saw the Green Monster and somehow I climbed over a bridge that made Everest seem small. In that last mile, my thighs burned and consciously with determination, my body-thoughts went to my thumbs, let them carry the run. As I turned a sharp but careful right onto Hereford Street, I saw one woman actually crawling on the road, grim finishing determination in her movement and when I looked back, a wide-eyed vacancy returned my brief glance and I couldn’t help but notice her sweat-lathered mouth and face; I ached for her and so wanted to help her and knew both that I couldn’t physically assist her and she wouldn’t want me to help.

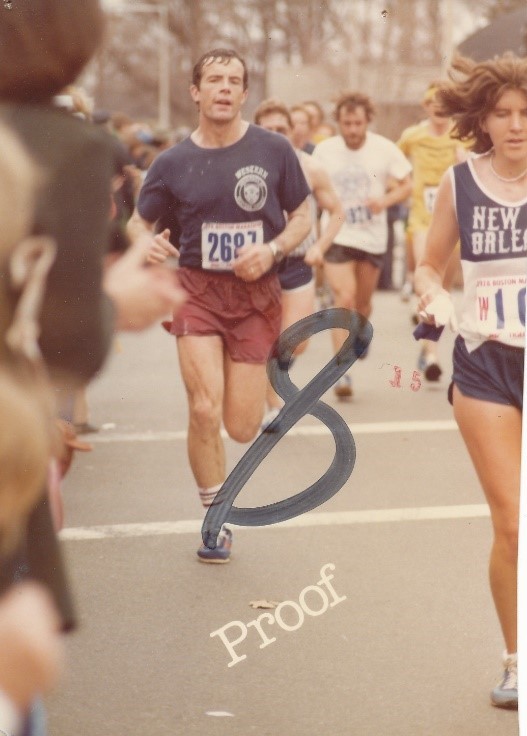

Would that the last two blocks could feel euphoric! Instead, I felt a kind of abject joy of the finishing effort, saw the 2:58 time as I crossed the finish line. Someone handed me a tinfoil blanket and a can of beer, a Schlitz I think, and no liquid ever tasted as good. In the bowels of The Pru, I retrieved my clothing bag and then decided sitting down before I undressed or got in the shower was the best thing to do. Runners were sitting on open toilets, others were being ushered to first-aid areas some with re-hydrating IVs attached to their arms. Uncontrollably, I started to shake and shiver for minutes and I just could not conceive of how to get undressed, let alone get up, least of all shower. At the same time, I felt the inner, deep satisfaction of having run as fast as I could run, for 26.2 miles and completed The Boston at that. One doesn’t do Boston; I learned Boston is about being a runner, not doing a marathon. And then Jerry came, clothing changed, and wordlessly removed this young man’s shoes and undressed and dressed him in act of what the young man felt at the time was an absolute feat of human kindness. Often, I tumble home to my memories of that Boston marathon.

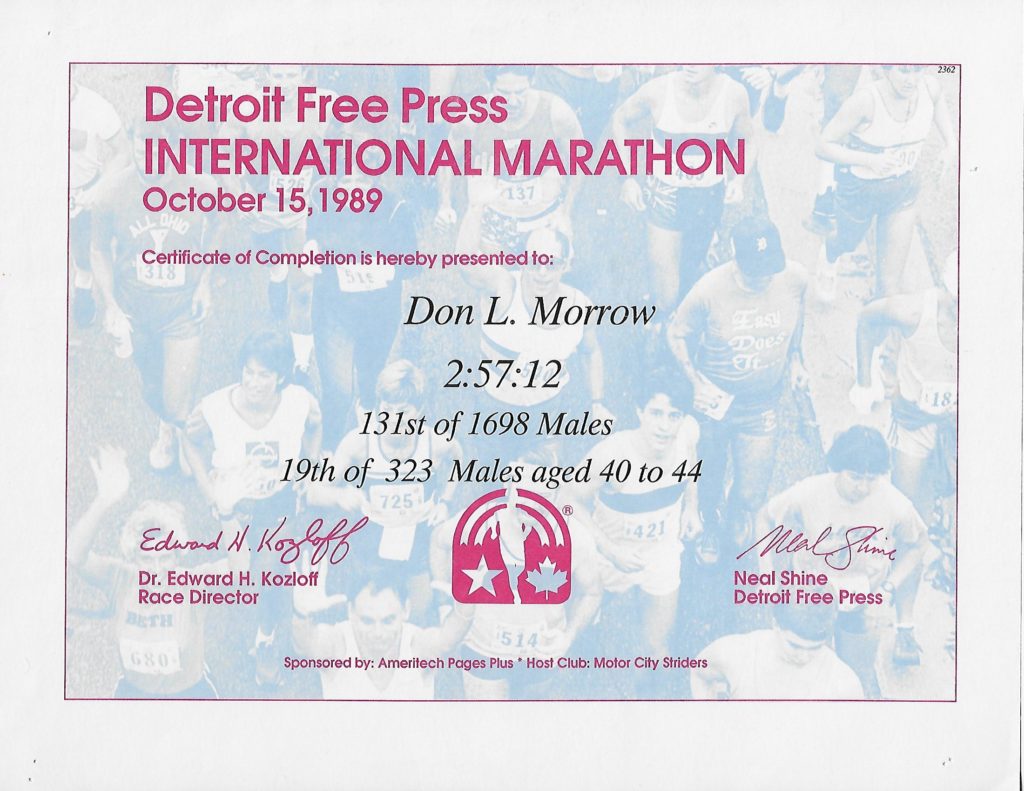

…over my running life, I completed more than 20 marathons, including two other Boston races. The only certificate of marathon completion I kept is this one from the 1989 Detroit marathon:

I ran Detroit twice, both times a kind of out and back C-shaped, flat-terrain circuit through police-guarded downtown areas to the exquisite Huntington Woods’ area finishing with a full lap of the perimeter of Belle Island. My time was among my best performances. In 2011, one of my sons ran his first Boston in 2:48, a full ten minutes, or, almost half a minute per mile faster than I ever did – perhaps he too chose his parents wisely. All three of my Boston marathon finishing times were within 3 minutes of each other. However, the real legacy given from Boston to me, has been an adult lifetime of daily, devoted, disciplined long-distance running. Finally, see my blog part tribute, part beatitude to my later in life, 10-year running companion, our Rhodesian Ridgeback, Temba at His Majesty.