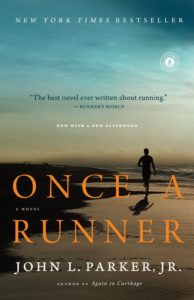

Today, on 28 June 2021 as if to reify and bolster my intention to start to write this blog, a book I had loaned was returned to me. It was this one:

The title always reminds me of the start of every good story, ‘once upon a time.’ In another blog, I have alluded to this book briefly. First published in 1978, Parker’s fictionalized account of Quenton Cassidy’s long distance running discipline, devotion, and physical skill remains the best selling running novel to date with over 100,000 copies sold. There is a sequel, Again to Carthage (2008) and a prequel, Running in the Rain (2015), neither of which appealed to me nearly as much as Once a Runner did and still does. Thematically, the book can be summed up in the author’s words:

You don’t become a runner by winning a morning workout. The only true way is to marshal the ferocity of your ambition over the course of many day, weeks, months, and (if you could finally come to accept it) years. The Trial of Miles; Miles of Trials ~ John L. Parker, emphasis mine

For many years, I included this book in my university teaching of sport literature classes’ fiction lists. The phrase, trial of miles, miles of trials could be applied to so many things in life, not merely in running. And running has been an almost life-long passion that I described in the blog, “run, …Boston” almost 2 years ago. For this requiem, two phrases keep ringing in my ears:

Trial of miles, miles of trials

and, for some months, hauntingly

Once a runner…

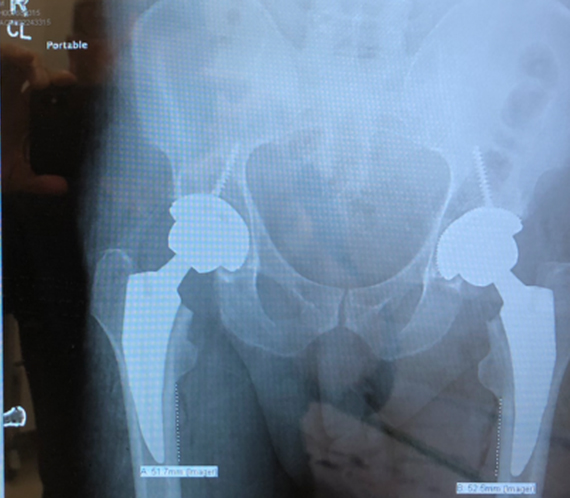

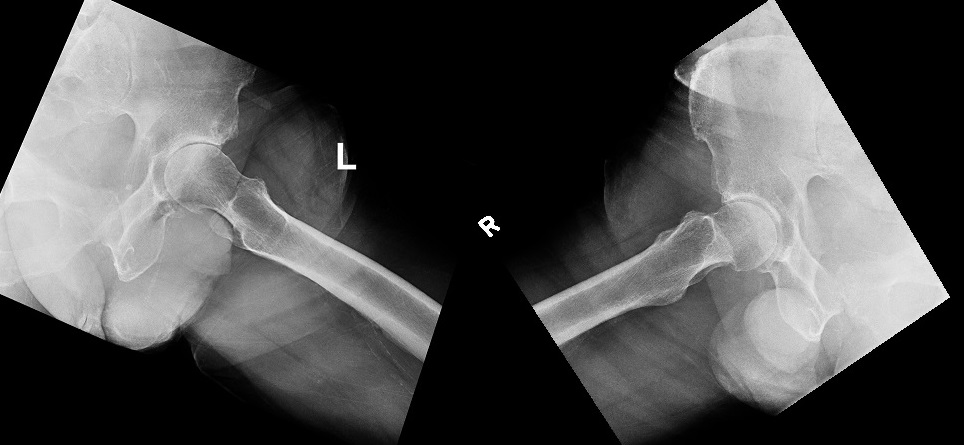

I am now, literally, once a runner. In early May 2021, I was x-ray diagnosed with advanced or severe osteoarthritis (OA) in my left hip; it requires full hip replacement surgery. The resident who first showed me my hips’ x-ray told me I had “advanced OA;” the attending orthopedic surgeon at Western’s Fowler-Kennedy sports medicine clinic, Dr Joseph, first viewing the x-ray in the doorway of the examining room office, some 15 feet away from the small computer screen, said, “oh my, that’s crummy!” Two months later, another ortho surgeon examining my x-rays, offered, in quite matter of fact fashion, “you have bone-on-bone OA.” At first, I wasn’t allowed to get the actual x-ray file; however, I was permitted to take a picture of the computer screen:

Reading x-rays is not my forte and yet, when pointed out, I can see the issue. The image is as though looking at my hips facing me. My left hip is on the right side of the image. The hip is a ball and socket joint so on both hips you can see the ‘ball’ of the head of the femur (thigh bone) inserting into the hip bones. On my right hip (left side of the image), there is space between the femur head and the hip bone; that is cartilage, not an empty space. There is no space between the head of my left femur and the hip bone on that side. And a larger image reveals small bony fragments or spurs that project from the head of the femur articulating with the hip bone joint surface. I have learned that those osteophytes are a major component of the joint pain. From the actual x-ray images…

In this image, my left hip (L) is on the left; right hip (R) on the right side. Comparing the two sides illumines the space between the ball of the femur and my right hip bone versus the lack of space – bone-on-bone – between those surfaces in my left hip.

In this image, my left hip (L) is on the left; right hip (R) on the right side. Comparing the two sides illumines the space between the ball of the femur and my right hip bone versus the lack of space – bone-on-bone – between those surfaces in my left hip.

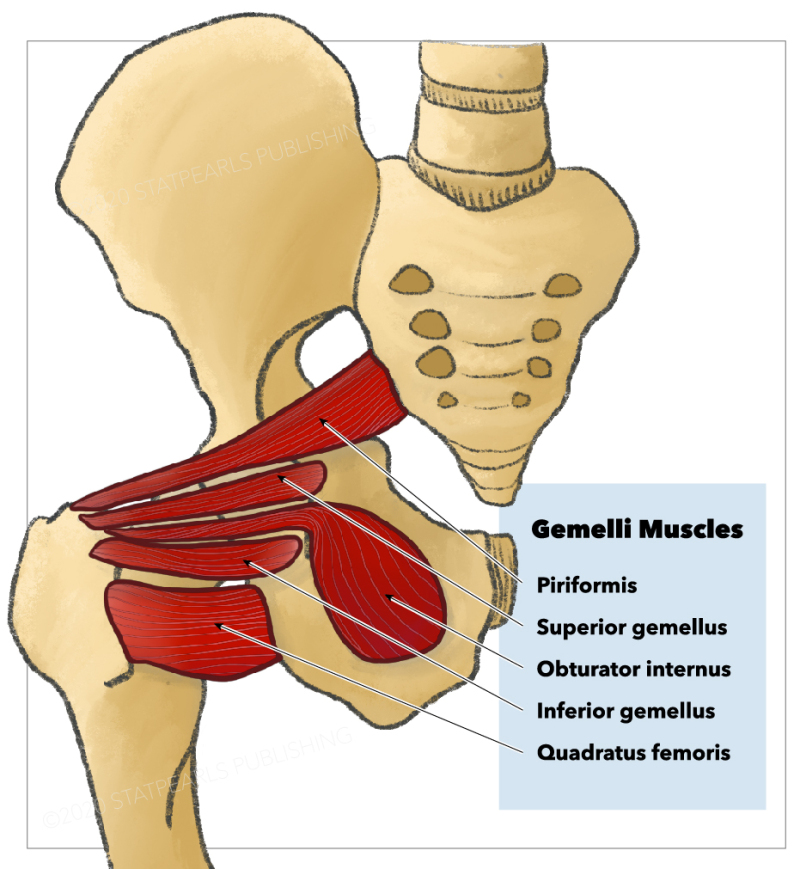

Managing osteoarthritis has become a daily discipline. For some 3-4 months pre x-ray diagnosis, I worked with my physiotherapist. Running had become increasingly difficult as had walking. At times, it felt like my leg wanted to kind of give-out or I would get a very sharp twinge of pain; if running, I was often able to walk for a while then resume running. When I couldn’t resolve the issue on my own I contacted my physio and, because of the Covid situation, we did virtual sessions, via Zoom wherein she would teach me different exercises that focused on stretching and strengthening major muscle groups – hamstrings, quadriceps, piriformis etc – trying to determine what was happening. Turns out, the hip is a complex joint; we even tried to isolate lesser known, smaller muscles like the gemellis, pictured in a right hip schematic below:

I experienced kind of mild relief of pain symptoms but unlike any other running injury I have encountered, progress seemed to be kind of, ironically, 2 steps forward, 3 steps back rather than any kind of progressive relief, even in cutting back on both running and walking. Finally, in late April, we set up our garage with our massage table, fans, and a heater and had my physio do a live visit, each of us sporting medical masks because of the pandemic. She did what is called a 4-quadrant test of the joint and said she felt sufficient restriction to warrant x-rays. Thus, the diagnosis described above.

By the time of the x-rays in early May, it was painful to walk, not impossible or debilitating but very sore. Even sitting meant I had to keep adjusting my position to alleviate pressure on the joint, likely the osteophytes exerting bone-on-bone pressure. Similarly with sleeping; even now I can only sleep on my right side; any downward or sideward pressure on my left knee is painful. On the advice of Dr Joesph, I tried Tylenol, extra strength for 10 days but it didn’t touch the pain. Advil seemed to work better so I went back on that medication and I opted to get 2 injections to manage the pain, a corticosteroid and a substance called hyaluronic acid, the latter a synthetic version of the fluid in all joints, synovial fluid that serves to nourish and cushion articular joint surfaces. Dr Joseph did the injections. With the freezing he did, there was no pain. However, I will never forget when he used ultrasound to guide the needles for the injections and was able to both see inside my hip joint and feel the pressure with needle insertions, he proclaimed, “my friend, you don’t just have inflammation in there, you have a raging inferno!” Not comforting and his declaration gave medical confirmation to the pain I was feeling. Very definitely, the injections have taken the edge off of pain. I still take Advil daily and also a hyaluronic acid oral supplement. So far, some 10 weeks since injections, pain only happens when I forget and pivot my left foot externally or internally. Walking in a straight line is easy, though slow with a pronounced limp. Walking around my home requires the most concentration because of all the turns one makes going from room to room or using stairs.

What was recommended to me was full hip replacement surgery. Early on, I was advised to look into a relatively new surgical technique called the direct anterior approach (DAA). Most hip replacements are done from the side or lateral aspect of the hip; earlier ones were even done from the back. The DAA is touted as ideal because it is much less muscle-invasive and recovery is easier. However, the DAA requires a special and expensive surgical table. After a kind of pre-surgical consultation with our local hospital system, the only locally available DAA orthopedic surgeons have a wait-list of 26 months or more. Covid hospital strain is likely responsible for all “non-essential” surgical wait-times. I was able to find a surgeon locally, at Strathroy Hospital, who does the lateral full hip replacement and his wait list is 7-11 months. He has a very good professional reputation and I have a consultation with him on 26 August. He does the lateral aspect surgery. As my GP, friends, and other folks advised me, by 12 weeks post-surgery, the result is the same. Healing may be slower with the lateral version but getting the surgery done is my paramount interest in getting back to normal function. Because of the injection substances now in my hip, the earliest I could have any hip surgery is 27 November; surgeons are wary of “product” (the injection substances) in the joint which bring high risk of infection until they run their course, presumably after 6 months. I do continue to look for DAA potential surgeries/surgeons in other geographical areas. Below is an x-ray image of full hip replacements of both hips (not mine) to show what the end result looks like:

Bottom line re my ambulatory prowess, I am a limper when I walk. Running is out of the question even just a few running steps. My physio asserts that at some point, I might be able to run a few kilometres post hip surgery. We shall see. How do I feel about all of this? From all I have read and learned about osteoarthritis, it seems I chose my parents poorly – OA is genetic. And, very likely, being a long distance runner, squash, badminton, and hockey player for more than 5 or 6 decades did wear on my joint tissues and exacerbated the OA to the point that it is now debilitating. I feel sad sometimes, wishing I could wake up and walk normally. Doing daily tasks that require weight-bearing is difficult; mowing the lawn especially painful so Jen is now the family “landscape architect,” as she calls herself. And, I have no choice but to manage movement. Unlike any other athletic injury, the OA in my hip can only be ameliorated with surgery and that is very different for me in that it is not something in my body that I can control. Instead, I kind of manage moving every time I walk. I’m not angry or frustrated. There are so many, many people dealing with health and chronic pain issues that are far, far greater than my OA. With hip surgery, I will be able to walk normally, even play my beloved pickleball as long as I do my post-surgical physio exercises. Lots of people I know with hip replacements proclaim how happy they are to be able to function normally. So, I feel hopeful, at times impatient to get the surgery done so I can get to the work of rehabilitation. Until then, I am resolved to move to the best of my ability, ask for help when I need it, and do all the exercises my physio has prescribed to keep my left hip muscles strong and my joint range of motion as flexible as possible. Jen provides the greatest support and empathy and I am extremely fortunate to have such a kind and loving partner in this process and just in life.

What I do need to do is say good-bye to the runner that was within me for so much of my life. As I write that last sentence, in my head I hum Chris de Burgh’s anthem Say Goodbye to It All, a threnody itself and hence this requiem prefaced by my OA context. It is so difficult to put what was always a physical experience into words; running does not translate into language easily. Running was a gift to my body and my being that I relished for 50 years. It was joy; it was agony, sometimes both. It is physical and elemental, a mantle or cloak I put on internally. There is no implement or equipment beyond shoes and apparel, the latter just prerequisites to any run. Often, I thought of Alan Sillitoe’s main character Colin Smith in the novella The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1959). Smith is a working class…

“… troubled young man sent to a reform school after he robs a bakery. A gifted runner, he is chosen to represent the institution in a key long-distance race against a prestigious school. Much of the story is told in flashback and inner monologue, revealing the thoughts of the young man as he struggles with his identity while incessantly practicing in preparation for the big race. The finale finds him enacting a startling gesture of defiance: he stops near the finish line and lets the other runners pass.”

Among the many aspects of the book I ruminated on, I enjoyed Smith’s reflections on running – early morning runs “without a crust of bread in your guts.” There are so many gems about running in the book. What I never felt in running was ‘loneliness.’ I did not feel lonely; when I ran by myself by choice, I felt and exalted in being alone. There is a big difference between alone-ness and loneliness, in my view.

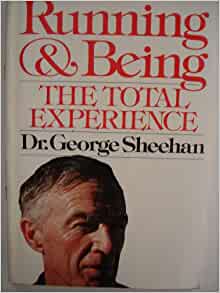

Running alone is special. It is just you and your repeated, pedal thrusts against gravity. The more I ran the more I learned about running, how to run from my hips; minimize upper body movements; move each arm aligned in kind of a juxtaposition with its opposite knee. Running is predicated on your thumbs and their unison trajectory with each knee, all movement directed forward. There is a fluidity of running motion, a groove that moves with and within me. I don’t think I ever felt the vaunted runner’s high, the apparent endorphin-induced euphoria of running in some zone. But I often felt so good, so comfortable in my body that running was easy, a plumb-bob in motion. The guru of long distance running in the 1970s, the decade when I started on that adventure, was a medical doctor George Sheehan. A converted runner, Sheehan had a wonderful, 3-word expression that encapsulated and encapsulates how I felt and feel about running – it is, every single time you run, an “experiment of one.” Each time is a trial of miles and/or miles of trials. I gobbled up Sheehan’s 1978 book . . .

And I drank Sheehan’s kool-aid because I felt it – running was always about being, always a total experience. Just as you can never step in the same river twice, so too no two runs are ever the same. I felt running; sometimes in sync, sometimes the fun left the run (as Quenton often opined in Once a Runner) when it got hard and still you/I ran.

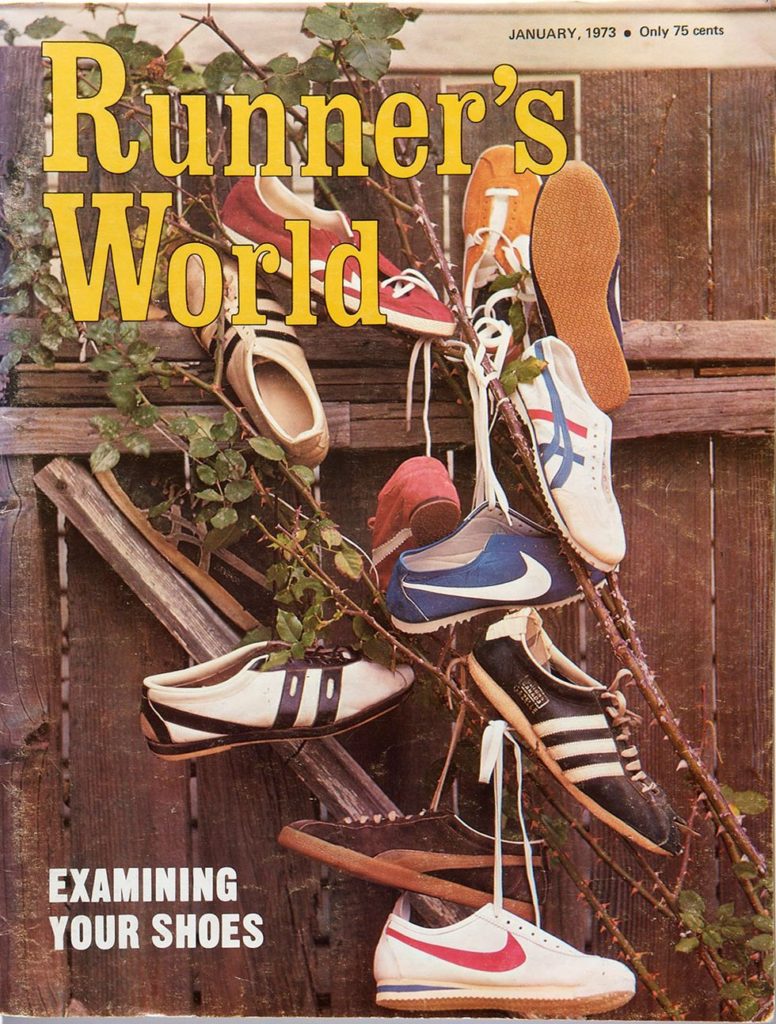

Another important script that bolstered my devotion and addiction to running was Runner’s World, a monthly magazine that has catered to “runners of all skill sets” since 1966

For more than 10 years, I eagerly awaited my subscription mail-delivery of each new issue of RW. The 1973 example above was chosen because it illustrates the kind of shoes in existence in my early days of running. The magazine title was important to me with its singular possessive title, Runner’s not Runners’ and silly as it sounds, to a word-person and grammarian like me, this was a magazine for me personally even though, clearly, it was for runners everywhere. However, the periodical lost its enchantment to me when it became more of a fashion magazine, in my view, than it had served as my window into running advice, news, tips, and stories.

I remember routes and unique events that happened while running those routes. Late in my running career, gifted with a Nike watch from Jen in 2015, I joined the Nike Run Club drawn to its route-tracking and -mapping feature. If I remembered to start the watch on a run, it would record the route and provide a map with distances, splits, places I stopped etc. When I acquired an Apple watch in 2018, I downloaded the run club app for that device. For my first use of the new watch, I was running on a back-country road near a cottage we had rented. As I headed out from the cottage, I started my watch to record the route, as I had become accustomed. However, I was unaware that I could adjust the pre-sets on the new device; the old watch was little more than a monitoring device. At 1 kilometer into my run with just bush surrounding me in a stillness void of people, cars or other cottages, came a disconcertingly loud voice from my watch, “TIME…6 minutes…” and I think I jumped straight up in the air! I had no idea it would be an audible report and I laughed at myself, foolishly relieved it was not a bear or someone shouting at me. What I did enjoy about the Nike mapping was looking at routes traced on the device just to see the different routes, water stops…times, either total or splits per km were never of much interest. My last run was 16 Feb 2021 captured in this map…

The route is one I and we (Jen and/or our dogs) covered many times over the last 20 years, totally within the perimeter of our neighbourhood from our home to the easternmost street in Kilworth and back home. This run was solo and the red and yellow colours at the farthest street and at the end represent the places where I walked because of muscle and/or hip soreness. Sadly, it was my last running effort for all the reasons described earlier. Curiously, I am reminded of Robert Frost’s line from After Apple Picking, “but I am done with apple picking now.” And I feel ‘i am done with running now‘ not as pity, rather as reality, my new normal. I will pick ‘new apples.’

I have so many, many wonderful memories of runs over my half century of running. And I’m not certain when it all got started. My earliest memory of trying running for its own sake – as compared to the running required in a team or individual sport – was sometime in the mid-1960s in high school. One of my friends was on the track or cross-country team and in the off season, he and his team mates would steal wrestling team skipping ropes and tie the third floor mid-hallway fire doors open after classes and run circuits on that presumably deserted floor. Curiously, what drew me to trying out the activity was the fact that my friend had “pigeon chest,” a condition when the breast bone is pushed forward. Somehow, in my mind, I theorized what made him fast was that his chest was decidedly aerodynamic. Thus, I sought to run with him, as I recall, to test out my theory on his ability to run so well. Unable to confirm my odd hypothesis, I think I tried the hallway circuits once and did not get the attraction and pretty much decided continuous running was anathema to me.

My foray into running for its own sake started out as a utilitarian project to lose 30 pounds I had gained during my Master’s thesis writing. In Edmonton, starting my doctoral work at the University of Alberta, I began running a few blocks and built gradually toward a few miles, sporting my squash court running shoes. Buttressed by the then popular grapefruit diet, I did lose the weight in about a year. By the time I started to work at Western University in 1974, running a few miles a day had become a kind of discipline for me – it and I felt good. I was hooked. My colleague and friend, Jerry Gonser, a former miler at the University of Michigan was an outstanding long distance runner and we began running together at noon hours either just the two of us or with other runners, students and/or staff/faculty. Jerry was a veritable fountain of running wisdom with regard to technique, pacing, hill-running, fartleks (speed intervals), and just sheer enjoyment. We ran together for more than 20 years, I think, until he retired from the university. Invariably, Jerry would come to my office and inquire, “Morrow, you ‘goona frog around here all day or go for a run?” The locker room at mid-day in Thames Hall was always filled with people, students suiting up for PE classes, faculty/staff dressing for or showering after working out, always kibitzing good naturedly about events of the day, who was on the A-team for running, what the weather was like for working out, anything and everything.

Within a few years, under Jerry’s tutelage, I was running anything from 5 to 10 miles a day. We had two favourite 5-mile routes; one was the “A. C. (Claude) Turner 5” named in honour of an older colleague and runner who lived near Westminster College and even though he suffered from dementia, came to the university to do physio exercises daily. The AC Turner 5 took us behind Brescia University Colllege into the Sherwood Forest – I loved that we ran through a place with that name, hearkening back to my love of Robin Hood television shows and folklore – neighbourhood. We would do the hairpin turn at Wonderland and Gainsborough (to ensure we did the “full 5” miles), head south on Wonderland and then back toward Western on Sarnia Road, always “doing” Gunn Lane’s steep hill finishing on Brescia Lane. Our other route was the “Jackson 5,” somehow attributed to our friend and fellow runner, Terry Jackson. The route was south on Western Road/Wharncliffe to Blackfriars, over the old bridge, along Albert Street and then north on Richmond and back to Western. After each run, we’d perspire and do sit-ups outside Thames Hall in good weather, if not, straight to the showers, rarely, if ever, talking about the run but just about any other topic. With changing before and after those 5-mile runs, it was about 70 minutes of total time. We averaged 7-minute miles for the runs, fast enough to be challenging and slow enough to talk and listen with reasonable comfort. It was time not-working at work and it was common practice on campus. If we were training for marathons, as I did from the late 1970s to early 1990s, we’d often do 10 mile runs either south toward Commissioner’s Road and back on Ridout or north to Arva and at that intersection either east to Adelaide or west to Wonderland and back into the university. Sometimes, we would do a route that I always found more challenging, through Greenway and Springbank parks, over the footbridge by the Thames Hall golf course and back along Riverside Drive. The 10-mile runs obviously took more total time, the runs 65-70 minutes and so we tended to get changed faster for those runs.

To this day, I don’t know if I loved running or I was addicted, perhaps both. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, I sang my body electric. Whitman’s 1855 poem, “I sing the Body Electric” was divided into 9 sections, each section celebrating some different aspect of human physicality; part of the poem is reproduced below:

Whitman’s phrase/title was popularized in the 1980 Fame musical,

I sing the body electric. For me, those words distill how I felt about running and often while on runs. I am not at all musically-inclined, sadly, but I love pop music. When I ran alone, lines from songs often burst into my head and became ear-worms during whole runs. There was no rhyme or reason which song or verse, certainly never mirroring my running cadence, just lines that repeated themselves over and over along my routes and the beauty was, I could get the words completely wrong and still they would ring true in my running head. There is no way I can recall which song-lines reverberated over the years but I can remember some of them…

I am just a boxer though my story’s seldom told, I have squandered…

We come on the Sloop John B, my grandfather and me

Love is a rose but you better not pick it, it only grows when it’s on the vine

It was a one-eyed, one-horned flying purple people-eater…

I can see Clearly now the rain [often substituted Lorraine, for those aware of this take-off] has gone…

Some velvet mornin’ when I’m straight / I’m gonna open up your gate

Big John, big, bad John…

One night a wild young cowboy came in / wild as the west Texas wind…

Monday, Monday…

I was born under a wandrin’ star…

Barcelona!

Bang the drum slowly play the pipe lowly / To dust be returning from dust we begin

Hello Darkness, my old Friend, I’ve come to talk with you again

Save a horse, ride a cowboy

Raindrops keep fallin’ on my head but just like the guy whose feet…

Bicycle. Bicycle. I want to ride my bicycle…

They call the wind Mariah…

and, most recently,

She thinks my tractor’s sexy; she even digs my farmer’s tan

Those lyrics came to me evanescently as I ran and were often as forgotten after my run as they were remembered.

Often people asked me what I thought about, frequently after they had driven by me running out in the country far from home. I always found it an odd question – what would be any different about my thought process – or anyone’s thought process – just because I was running. And yet with some empathy, I have often wondered what goes through a concert pianist’s head as they are playing some complex opus. My self-response to my thought process was I thought about anything and probably everything – sex, weather, events of the day – there was nothing different about my thinking during running. Often, before retirement, I designed the fundamental points I wanted to make in an upcoming lecture, or, I would think of points I should have made in a lecture just completed. And I would compose research articles, miffed when I got back that I could not recall the ‘brilliance’ of what I had brain-written. Sometimes, perhaps very often, I honestly thought of nothing – I just ran completely focused on the run, how I felt, being fully aware of my body while inside my body. One person, a non-runner said running can’t be fun because runners never smile when they run; a friend reminisced that she saw me in the early 1990s on a country run wearing my “Mona Lisa smile” – some truth to her observation, I suspect. Marathons, those 42.2 km events always seemed to require the most concentration on running. Always checking in with my body, trying not to listen to other runners or compete against them…just stay in my run. Still, distractions crept in – thinking of friends or loved ones or seeing a spectator sitting, relaxed, unburdened by completing a marathon. I had to learn to dismiss those thoughts – not-finishing a marathon, said Jerry, is not an option.

Sundays. Sundays were special running days for me for decades. Saturdays were always my day off running, reserved in winter for pickup hockey games at Western’s Thompson Arena. When training for marathons, Sundays invariably were long-run days and the truth is, I often enjoyed those arduous ramp-up runs – 13 miles, 15 miles, 18 miles, 22 miles – more than I did the marathon for which I was training; the marathon event was almost anti-climactic. I knew within 5 minutes what my finishing time would be based on how I had trained and my acquired sense of pace. In my prime of running, long before I ever started to wear a watch while running, I could tell my pace per mile within seconds, I could just sense it. I knew both the potential of my running body and its limits. Sunday runs became my trial of miles and yet I came to value those long runs that I made them a habit even when not training for and long after I quit marathon events in the early 1990s. At the time, I sustained a hairline fracture of my medial sesamoid bone under my right great toe. After one steroid injection, the medical advice I had was stop running marathons in favour of being a life-long runner or keep training for that distance and eventually, not be able to run. How interesting that the same situation applies now with osteoarthritis except that running is no longer an option. I continued to run long – 13-15 miles – on Sundays into my 70s albeit slower runs gauged in kilometres – 15-20 km to keep the absolute value of the distances – as I aged into my running body. Some runs and races were hard; I had to work for them and during them. For other runs, I floated. If I did a long run or didn’t sleep well or had some other ‘disturbance in the force’ of my running, the impact always happened 2 days after the interruption, not the next day, no idea of the reason.

Injuries for me were relatively rare. I hypothesize that doing other activities like ice hockey and squash, meant my body was not just a running body. In reality, I believe, running is at its core, a quadriceps’ (front thigh muscles) endurance-based regime. Obviously, it is aerobic and demands a good circulatory system – apparently, I chose my parents wisely for that latter gift – but, the repeated thousands of steps commuted linearly, against gravity translated into a premium placed on my quads and all the forces transferred up into my body from my feet. Thus, I encountered plantaris muscle (small, narrow calf muscle) strain, small tears in my hamstrings, back soreness, “blackened” toenails from the ends of my feet sliding into the toe-box of running shoes during downhill running (or sudden stops in squash-playing). Sometimes those injuries required time off running but rarely for more than a couple of weeks. Running with Jerry meant I learned how to run – heel-around-laterally-to-toe foot placement, using my thumbs, running with my hips forward, plumb-bob-like etc and I think that body education kept me relatively injury-free.

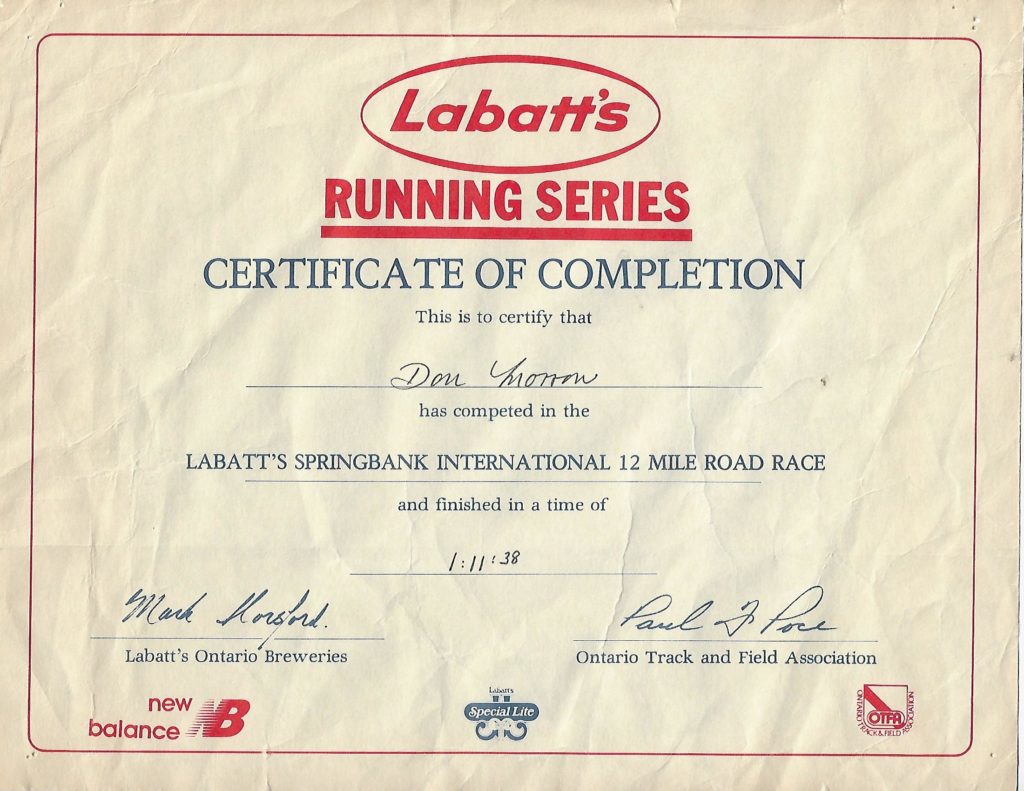

In my experience, I was a better than average runner in terms of pace, speed, and endurance. I enjoyed daily runs, especially Sunday ones much more than races and I did run my share of 5-mile, 10-mile (the local Watford 10-miler from Alvinston to Watford almost annually for many years), 10 km, relay distance races, and marathons perhaps 25 of the latter (see my

run, … Boston blog on marathoning experiences). My favourite race was an unusual distance, 12 miles in the annual Springbank International Road Race that took place in the Fall. Below is the certificate of completion from one of those years, early 1980s I would think:

My time reflects my pace, just under 6 minutes per mile, a tempo I could hold in races up to that distance; in marathons, my rate was consistently 7-minutes per mile. What I enjoyed about the Springbank races was that they were held in London’s park of the same name, 4 laps of the perimeter park road, mostly flat with one hill near the dam, about half a mile from the start/finish line. Heavily sponsored, the event attracted some of the best runners in North America – Bill Rodgers, Frank Shorter, and Canadian Jerome Drayton, come to mind. Of course, I never saw them except for the humbling occurrence on my 3rd lap just reaching the aforementioned hill where, often, the two lead racers or lead pack, lapped me as they sprinted up the hill completing their 4th lap. I distinctly remember one year when Rodgers and Drayton flew past me at the bottom of the hill and where I would run the hill staying on the left edge conserving energy and covering less distance , they were going so fast – probably 4 minute, 30 second miles or better – that they had to swing out to the right to make the turn at the top of the hill without breaking stride. I was in awe of their running gifts and abilities. The other lure to this event was observing the miniature railway tracks, sometimes even the train on each lap:

Springbank Park is famous for its beauty, its renowned Storybook Gardens catering to children’s fairytale imaginations, and the miniature train. For me, on each circuit during the races, seeing the tiny train tracks brought back memories of my dad bringing me and my sisters to the park when we were young and my yearning each time to ride the “Springbank Express.”

Just as with the unorthodox 12-mile event, I think of the many odd occurrences that happened to me on runs. By choice and privilege, I have run with dogs that I or we have owned – Ben, my Irish Setter [Benjamin Patrick, his second name to honour the second name of my good friend in my Undergraduate class]; Temba, our Rhodesian Ridgeback whose running prowess I consecrated in a blog called

His Majesty devoted just to my ten years of adventures with him; Cheko, our magnificent, perfectly proportioned Ridgeback who left us way too early at 6 years; and most recently, our two Portuguese Water dogs, Jazmine and Tiso. Unless I were able to run on deserted trails, mostly they ran on leash beside or in front of me. They were all incredible running mates, each with different personalities and each beautiful to watch in stride and such a comfort to have with me in the silence of our running footfalls. And I talked with them, sharing what I was feeling or thinking, making them aware of something coming up on our routes and just generally revelling in their company.

Other than my menagerie of canine running companions, some of the curious events that happened on my runs are still fresh in my mind’s eye. One very cold, stormy winter day in February, perhaps 25 years ago, I left Thames Hall and headed out the main university gates and turned north on Richmond Street. I was by myself and almost turned back because of the heaviness of the blowing snow. There were hardly any cars around, let alone pedestrians so I stayed on the sidewalk rather than my preference of road-edge, facing oncoming traffic. As I approached the 4 large apartment buildings, I saw a solitary figure, a woman, stooped, her head and face down toward the ground, clad in a huge overcoat and a scarf. She was shuffling very carefully and I adjudged that I needed to be careful because we would likely meet. Wary of scaring her, I slowed my pace. As I neared her, she stopped and her right arm eased out from her side toward me. Just as I came up to her, I saw she was extending an envelope toward me. Without raising her head or looking at me, she said, “drop this in the box please.” In semi-stunned silence and awe, I took the envelope from her; she turned and mosied back toward her apartment building. I checked that the envelope was addressed and stamped and placed it in the mailbox slot about 200 feet up the sidewalk. Her timing was perfect and I was bemused my whole run recalling the experience.

When I lived in north London, my Sunday runs were normally out on the country concessions. Highbury Avenue north of Fanshawe was less busy with traffic than it is now and the Sunningdale and Medway concession roads offered wide shoulders and lots of beautiful homes, horse farms, and golf courses as “my” scenery. Vividly, I recollect being quite stunned at the affrontery and just lack of respect of one farm with a black-faced, porcelain figure, legs-crossed sitting on the edge of a well-wall in the front yard; it was there for years. For some reason, I loved the challenge of running up hills. As an aside, I always wanted to run the escarpment hill on the 403 highway coming out of Ancaster. It was a fantasy because it was 3 lanes of traffic in both directions and always busy and no trail beside the road. But the hill was steep and about 2 miles’ long, I imagined. At any rate, the best hill on my routes in north London, was that one that arose from Adelaide Street ascending west up Sunningdale Road. Often, I used it to do wind sprints when I was training for marathons. One Sunday, my oldest son, Matt asked if he and his best friend Andrew could come with me on my run riding their trail bikes along beside me. I agreed knowing few vehicles traversed the roads along Adelaide, particularly early on a Sunday morning. The boys were perhaps 7 years of age. We left on a cool Spring morning and chatted as we went along. Not immediately conscious of the fact that their bikes were one speed, no gears, I turned onto Sunningdale from Adelaide and accelerated up the hill. Quickly, I realized the boys were not with me, stopped and saw them pulled up and standing beside their bikes unable to negotiate the hill. I smiled, ran back to them, had them mount their bikes, and with one rider on each side of me, I put each hand on the back of their bicycle seats and pushed them up the hill in running stride. I thought nothing of it at the time, just something that needed to happen.

Seasonally, it was as though living canvases were transformed in the landscapes I traversed. I loved trail-running, especially the route around the perimiter of Western’s campus, through the playing fields, down along the Thames river, across Windermere and in behind Huron College on the ‘flats’ used for cross-country races – 5 miles of mostly tree-covered paths. My very favourite trail – aside from the Chuckanut Trail, an out-and-back, gorgeous 7-mile trail near Bellingham, Washington – was the Komoka trail all through the woods and along the south branch of the Thames River:

Autumn, my favourite running season, on the Komoka Park trail…

There are 5 sets of wooden bridges along the Komoka Park trail, this the last set before the upper trail section

Behind our home in Kilworth, I could go out the back gate into the splendour of trails that started in the farmer’s field and progressed into the west end of Komoka Provincial Park; only ice prevented me from running the trails behind our house. There are two scenes I remember distinctly that marked the seasons on that route. One was late-Spring, early Summer tent caterpillars festooning the trees all along the upper path along the quarries. Destructive and icky-looking, they appeared every year. The other was in sharp contrast but still featuring insects. In late September, perhaps early October annually, as the dew got heavier, in two meadowed areas along the trail, the flat expanse in the early morning would be resplendent with what I labelled an orgasm – no idea why but no more odd than a murder of crows or pride of lions or walk of snipes – of horizontal spider webs, hundreds and hundreds of these gossamer lattices. They were beautiful and only appeared for about a week each year.

When I used to teach a week-long canoe-skills’ course at Camp Ak-o-mak near Parry Sound, each morning began at 6:30 with a loud bell rousing everyone up for pre-breakfast run, swim, or canoe compulsory activities to start the day. My choice was to co-lead, with Jerry Gonser, the students on runs through the woods. It was not uncommon to see bears in early September. Etched in my mind is one run over these hilly, gravel roads. All of a sudden, one student right beside me, tripped, fell, did a complete sumersault, landed on his feet and never broke stride. We were stunned, awarded him 10 points for style. It happened in an eye-blink, those moments when everything seems to be in slow-motion, normal time is suspended. That same time-stopping experience occurred once with Temba as we finished our run just behind our own back yard and we were on our cool-down walk at the end of the farmer’s field. As we turned and went up the slight rise near our back yard, we saw the biggest, full-antlered buck I have ever seen. He stood atop the berm, completely still, staring at us. We stopped, Temba’s hackles piloerected but he stood beside me, quiet, kind of on-point toward the wild animal. Slowly, very slowly we backed up; the buck never moved but followed us with his eyes til we got into our yard and shut the gate. Later, I checked with one of my colleagues, an inveterate deer-hunter, related the event to him and he chuckled then opined it was rutting season and Temba, being reddish-brown in colour and large for a Rhodesian, was looking very attractive to the stag.

And then there was the extraordinary ordinariness of running. All my runs reflected discipline and normalcy, patterns of coveted behaviour. My father was the most disciplined person I have ever known. For example, each time he took his shoes off, he would loosen the top two rows of laces, gently lift the tongues, and place them neatly in the row beside all his other shoes. I was amused and wondered, who would ever do that? I did that with my running shoes after each and every run. In the same vein, preparing to run almost never varied for me in 50 years. Late on running mornings, I would do sit-ups, 150 of them based on a firm belief in maintaining strong core muscles, hamstring stretches on my back, legs almost straight up in the air (very tight hams, akin to most runners). Then I would get changed prefaced by a liberal application of petroleum jelly high on the inside of my thighs to prevent chafing – I wonder now how many jars of Vaseline I went through in all those years – then t-shirt, shorts in warmer weather, running tights when colder, sweatshirt if needed (I had 2 of Jen’s Work That Body gym-logo sweatshirts I wore for about 15 years), and always, always my Thorlo-brand socks, mid-calf length, double-layered, perfect for foot comfort:

In fact, every Christmas or birthday, I would request Thorlos as a gift-wish. At the door, whether Thames Hall’s south-facing single exit door 5-stairs, or the foyer of my home front doors, I’d do ankle and calf stretches, and, ironically now with hip osteoarthritis, hip stretches. Then I’d ‘don’ a jacket (loved the long-back, over-the-bum rowing jackets), peaked cap or tuque, gloves or mitts, again, all apparel weather-dictated. For over 30 years, I never took water containers with me on runs. I should have and often ‘stole’ water from hoses coiled beside houses on my routes or pre-planted bottles of water on marathon training runs. For the last at least 15 years, I took water on almost every run, all year and shared it with my dogs at water- and stretch-stops. My fondest water story is that of runs along Oxbow Road past the two golf courses between Gainsborough (or the Nairn Road) and Komoka Road.

I never wore head phones or ear-buds, preferring to be both alone in my running solitude and to be safe in hearing what might be approaching or happening around me. Over the years, it has been my privilege to have run in storied and exotic places like Melbourne and Perth, Australia, Dublin, Barcelona Florence, Pratola Peligna in Italy, Fish Hoek, South Africa, and the perimeter of the Jakarta (Indonesia) International Airport, the latter on a layover en route to Australia, the airport deserted in the early morning except for a single burned or bombed out shell of a car abandoned directly in front of the terminal. For conferences and holidays, whatever city I visited in North America, I would always go for early morning runs, by far the best way to get to know city venues, streets, parks, and waterways. Some of those runs carried more adventures than others; in Louisville, KY, I got lost on a mountain and was rescued by the kindest, backwoods’ mountain men who fulfilled every stereotype I had of them and yet they graciously rendered clear directions back to the University of Louisville; in Manhattan…Kansas (who knew) I was lured to a huge bank of lights I could see even in broad daylight in the distance – it turned out to be one of the largest football stadia I had ever seen, home to the Kansas State University Wildcats; and in late May on a 14-mile run along the banks of the North Saskatchewan River is Saskatoon, the prairie city temperature was in the 30s Celsius and about 10 miles into the run, I tought I was dehydrated and hallucinating in seeing pelicans floating on the cool river – turned out, pelicans do frequent Saskatoon. About the most curious thing I witnessed in my last couple of years of running was kind of statue in the side yard of a house in Komoka, right near a railway underpass; it was and is fully reconstructed, life-sized skeleton of a horse. The owners often decorate it with orange and black ornaments for Hallowe’en; I did a double-take when I first spied it, wondering how long it had been there, perhaps escaping my notice. Was it the remains of some animal they loved? Strange and eerie to encounter every time I ran past.

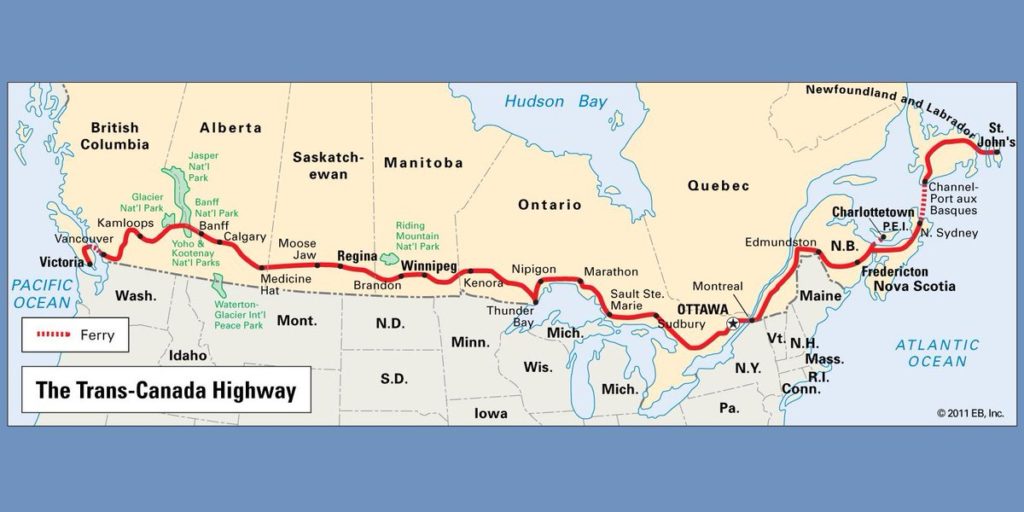

I ran year-round; only two conditions stopped me from running – lightning/thunder storms and temperatures of -20 Celsius or lower, the latter conditions meant the risk of frostbite. Humidity I hated, drained me as a runner but it rarely stopped me from running, just adjusting my distance to shorter routes. Most runs were early- to mid-morning, or at noon hour when working. I far preferred running after dark; somehow it just felt freer but the issue was running on a relatively full stomach from dinner and the runs kind of revved up my metabolism and often I didn’t sleep well. Just for fun, I have estimated the number of miles I might have completed in my half century of running. If I use, conservatively, 35 miles per week for 48 weeks each year, allowing for days off, then each year I ran about 1500 miles. Over 50 years, that’s 75,000 miles or 16 trips across my country’s Trans Canada highway:

Isn’t that something, even hypothetically! And I write that not from my ego but from a place of gratitude and wonder. How many pairs of running shoes did I buy and wear out, careful always to replace them with the slightest wear in their soles. Similarly, how many kilos of ice did I use to cool post-run inflammations and injuries? Coincidentally, as I look at the map above and its labelled cities, I see only one – Nipigon – in which I have not run…a kind of pogo-like set of journeys across the nation over many years.

And I remain, once a runner, once upon my time. Not ever did I do a single distance one step longer than 26.2 miles. I am in awe, to understate my feeling, of athletes who do century, 100 mile runs or triathletes, like my son Joe, who in ironman events swim 2.5 miles, then bike 112 miles, and then run a full 26.2-mile marathon! Over the years, my addiction/devotion to running was encapsulated in Jerry’s proclamation, “you brush your teeth, you run.” It was a fact of habit in my daily life, my experiment of one. Just get out there, no matter the conditions. Do I miss my trial of miles and miles of trials and my sheer exuberance in the act of running? Of course. Writing this blog has been a kind of introspective exposition, a cocktail of movement memories. I needed to say good-bye to it all, in part to lament – my sense of the titled Requiem for this blog – the loss, and also to say my ave or all-hail acknowledgement to my running life, my running being. Today, I might hobble with osteoarthritis when I walk and yet even seeing runners in our ‘hood as I do so, I tumble home to the decades of running rapture I was privileged to experience. And finally, I move on – literally – to new physical endurance activities to manage my new normal, to be in my body now – to pick new “apples.” All to be revealed in my next blog…

In this image, my left hip (L) is on the left; right hip (R) on the right side. Comparing the two sides illumines the space between the ball of the femur and my right hip bone versus the lack of space – bone-on-bone – between those surfaces in my left hip.

In this image, my left hip (L) is on the left; right hip (R) on the right side. Comparing the two sides illumines the space between the ball of the femur and my right hip bone versus the lack of space – bone-on-bone – between those surfaces in my left hip.