Metropolitan Goth

A voice. During the 1960s, Reverend George W. Goth always began his sermons at Metropolitan United Church in London, Ontario with this invocation, “May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in Your sight, O Lord, my strength and my Redeemer.” I didn’t know it at the time but his words were taken from Psalm 19, verse 14. Between 1963 and 1969, I heard those words enunciated carefully, truthfully, sincerely from this bald pate minister in ‘my’ church. Clad in black robe adorned over his shoulders trailing down his torso was his bright red stole or vestment symbolizing his priestly authority as an ordained minister; his was a quietly imposing presence. During each service, when it came time for his sermon, he would cross from the pulpit on the right side of the chancel (see the sanctuary image below), pause when he reached the preaching pulpit on the left side as we all settled into our seats then deliver his “May the words…” doxology. What followed were sermons that, to me, were riveting, carefully crafted, erudite, and delivered devoid of visible notes or even speaking points. He spoke with his hands, smiling often as he rested his elbow on the podium his chin cupped in one hand. He would pause for about 10 seconds quite frequently as if gathering his thoughts or letting ours settle and always engaging the ‘room’ with his eloquence and his demeanor. He had a way of addressing each of us – I felt like he was speaking to me – from those in the main floor pews where my father sat to the balcony on Reverend Goth’s right where I was situated and even to the choir members seated behind him. And when I grew up – or so I mused – I wanted to be a george goth with all of his oratorical skills. In this blog I seek not just to remember Reverend Goth but even more I write to re/learn what I think about my connections with/to religion and spirituality spiraling, conch-like around and from Metropolitan Goth.

Metropolitan’s sanctuary as I remember it from the 1960s

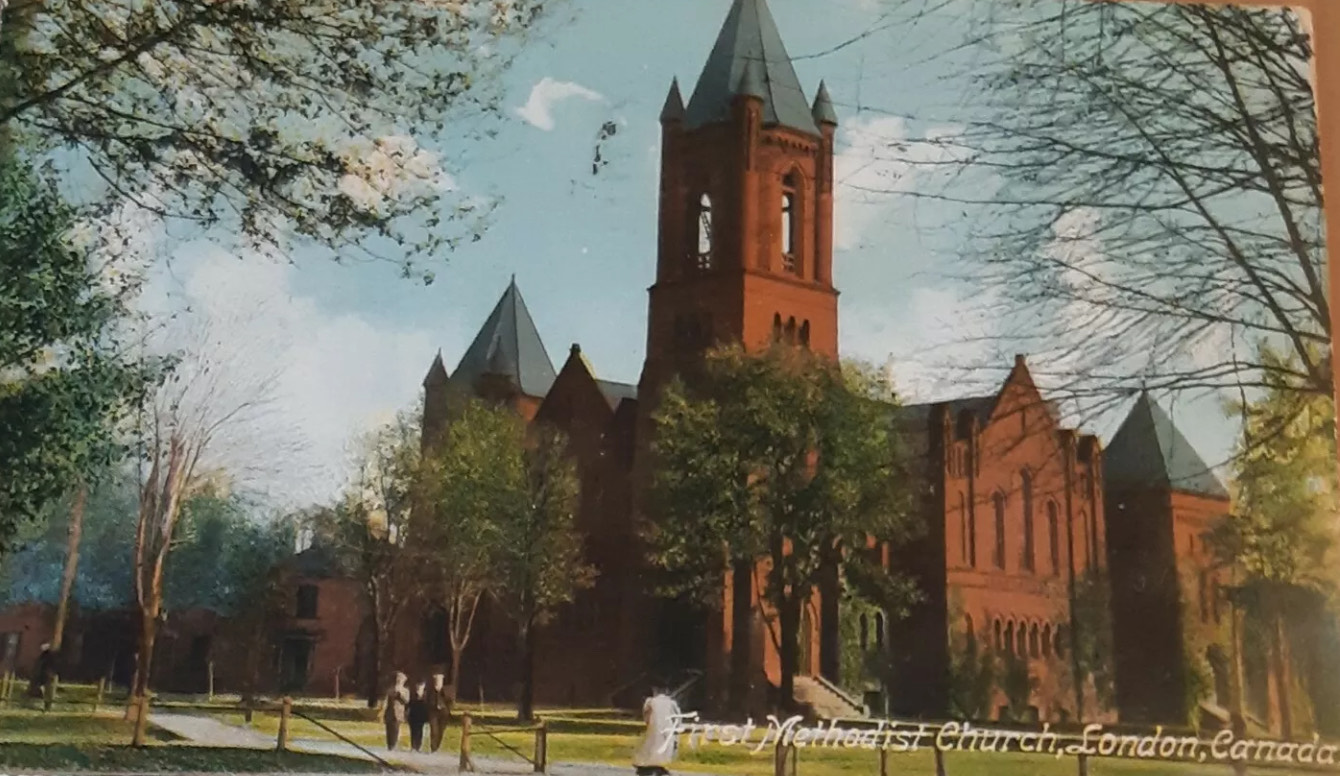

Metropolitan United Church was in itself an impressive edifice; the image below is the west-facing facade of the building located on the southeast corner of Dufferin and Wellington streets. It had and still has a majesty about it just in its structural and ecclesiastical detail.

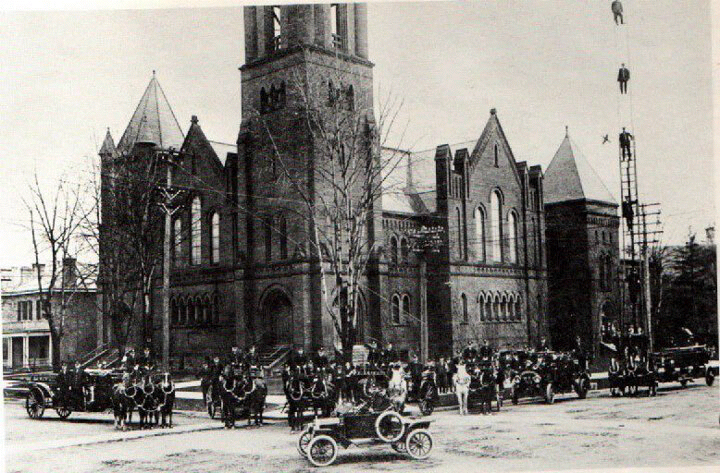

The earliest picture I could find of the church is this one…

Judging from the vehicles and horse-drawn carriages and what I assume is a fire brigade ladder featuring 5 bold persons along its height, the image is from the early 1900s, perhaps 10 years or so after the building’s completion in 1896. A more stylized even ethereal image of the church is this one when it was called the First Methodist Church:

The picture seems sort of fantastical, the hue of the brickwork almost reddish but otherwise fetching, to me, in its stately appearance. Perhaps it’s an artistic rendering, I’m not sure. Intriguingly, Metropolitan’s history dates back to as early as 1833 in temporary quarters with its first fixed structure completed in 1852 when it was known as North Street Church and occupied the southwest corner of Queen’s Avenue (then North Street) and Wellington Street. The North Street building was destroyed by fire in February 1895 and the conflagration story can be read at this site. Its 1896 replacement, First Methodist was re-named Metropolitan when the United Church of Canada was formed as a national body in 1925 and is now the largest Protestant denomination in the country.

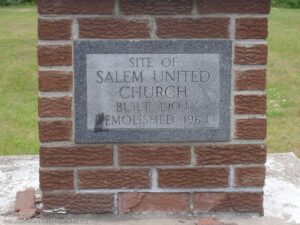

George Goth was appointed Metropolitan’s minister in 1948 and resigned in 1975. The United Church in general had been a staple institution during my youth. On the farm in Simcoe, every Sunday afternoon, my grandparents and any grandchildren staying with them attended Salem United Church located on highway 3 about 2 miles from their farm . . .

Salem United Church 1904-1964 plaque commemorating the edifice

and it was just a given that we went to church sitting on chairs amongst a very small congregation of farm folk and sang dirgy hymns – I can still hear my grandmother’s voice raised high in homage to the words of those devotional anthems, my own voice a bare whisper of respect to the rural requiems. My father was raised in the United church and my mother in the Presbyterian church. In fact, mom’s father was a Presbyterian minister. The two denominations merged into the United Church of Canada and as early as I can remember, our family of origin attended United churches. I suspect we attended church at the air force bases where we resided, in Centralia and Trenton; I have a vague recollection of the Trenton church. The most vivid memory I have of attending church in my elementary school days is that of Exeter United Church pictured below:

Located in James Street, just a few blocks from our home, we attended Sunday School every week when we lived in Exeter during my grade 6 to grade 8 school years. Vividly, I can remember those Sunday classes and my absolute a-religious focus on vaunted attendance records to earn the coveted Robert Raikes’ attendance pin each year:

While not an exact replica, the idea was clearly a Christian recruitment effort to instill regular Sunday School attendance, the name stemming from the person who initiated the Sunday School system as a form of working class social reform during the late 18th century in England. Getting each year’s pin was a ceremonial adventure and the medal-like badge was para-militaristic – befitting the son of an air force pilot-father – and a great source of pride, although totally devoid of any connection to Sunday School learning, just the accomplishment in and of itself in my boyhood experience. In fact, I do not have one retained memory of any Sunday School lesson short of learning the Protestant catechism via a popular instruction manual in question-and-answer format. That handbook had been used since the 16th century Reformation to teach core Christian doctrines, including the Ten Commandments, Apostles’ Creed, Lord’s Prayer, and sacraments, serving as a foundational tool for educating believers, especially the young, across Christian denominations. I do remember being enrolled by my father in Exeter’s Pentacostal Tabernacle church’s vacation bible school likely a summer respite for my dad as a single parent looking for something safe for his pre-teen son during the summer. My only memory from that experience was in wood-crafting a butterfly-shaped – its ‘wings’ at 90 degree angles to each other – corner sconce or shelf that hung in our homes for some years. Any differences between the United church and its Pentacostal counterpart were not apparent to me at the time.

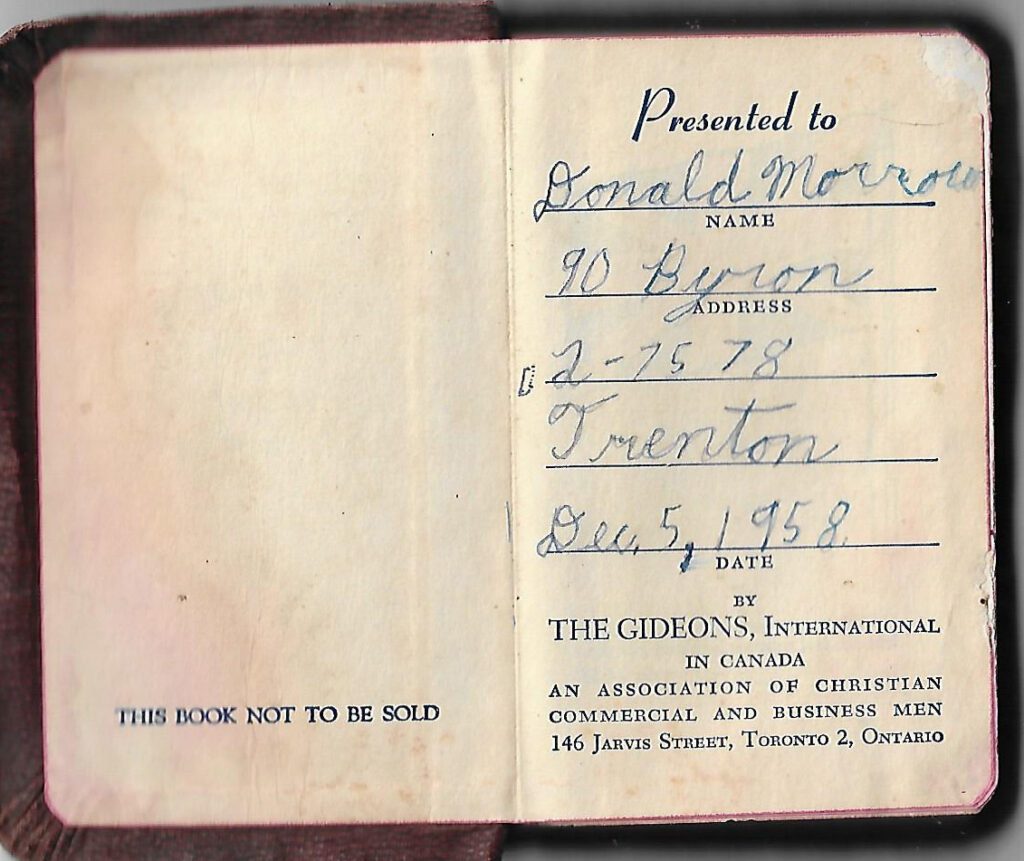

Thus, my indoctrination into the Christian United church began early and was fostered by my parents and grandparents. Church-going was normalized – it was a fact of every Sunday’s routine. I know I was baptized, very likely as a baby at some church in London when we lived in Dolton or Linwood streets before we moved to the air force base at Centralia. Other than the Raikes’ pins, an other memento of my United Church affiliation is this New Testament bible, the oldest personal religious relic I have retained and I know not the reason I have kept it:

Only 5 inches tall by 3 inches wide, I suspect it was given to Sunday School participants, on the occasion of their/my first communion. We lived at 90 Byron Street in Trenton where my father was stationed:

The house hasn’t changed much; I remember the small apartment building next door, an external milk-delivery cupboard with a small door at the side of the house, and that heating was via a coal-fed furnace. I was 9 years of age when I received this New Testament Bible as my signing and completing the inside presentation page attests:

The Gideons were an integral component of the international Christian dogma enterprise; they were and remain an evangelical group on a mission to spread “the Gospel.” As their current website avows:

Our single mission is to win others for the Lord Jesus Christ by strengthening one another, sharing the Gospel message, and distributing copies of God’s Word in hotels, hospitals, shelters, and other places where people often seek hope.

Thus, my little New Testament was a literally “shared” fragment of the Gideon industry. “Gospel” roughly translates as ‘good news’ and in Christianity it encapsulates a message about salvation by a divine figure, a savior (Jesus), who has brought peace and other benefits to humankind. My sense throughout all my Sunday School Christian priming was that attending church was more a routine, a lived experience…something we did as a family. However, I was never grabbed by religion in the sense of belief or doctrine. What I enjoyed was the regimen, the rewarded attendance, doing what almost every other person I knew did. Not to be disrespectful at all, but the Protestant Kool aid of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit/Ghost were more like apparitions or representations of the religion than beliefs for me both then and now. Curiously, I retain a distinct early childhood memory that the ‘second coming’ – marking eternal salvation – would take place physically at the small cemetery located in Centralia when ‘he’ (Jesus) would come to “judge the quick (those alive) and the dead” (Acts 10:42). That cemetery was/is just a cluster of headstones that my 5- or 6-year-old self assumed contained the remains of all humanity awaiting the second coming:

The graveyard’s (named Hick’s Bible Christian Cemetery, I recently discovered) deceased judged to be worthy, I imagined would be drawn skyward ghost-like into heaven. My childhood imagination even connected the air force base searchlight as useful both for night-guiding planes and the wisps ascending into heaven. Those ‘sinners’ not worthy in the judgement, presumably stayed there or went to hell to be tortured for eternity – how ‘christian’ was the notion of the fires of hell, as I came to question Christian doctrine in my late teens.

When we moved from Exeter to London in 1962, I’m not sure how my dad selected Metropolitan as our church of choice. I speculate that because it was a block away from the location of the YM-YWCA where my parents were married, perhaps Mom and Dad attended Metropolitan when they lived in London (in various streets – Victoria, Dolton, and Linwood) during the 1940s/early 1950s.

I believe this was my parents’ home in Victoria Street. My mother, pictured above lived there when dad was overseas during WW II

Regardless of the reason for the our church choice, the fit seemed easy. We moved into our rented home at 1305 Dundas Street (long since demolished and now occupied by an auto parts’ store), technically in the east end of London – at Highbury and Dundas – diagonally across from my high school, Sir Adam Beck Collegiate Institute. Metropolitan church was less than a 10-minute drive, perhaps 4 km in distance. At first, I think we attended church services with my father. To this day, I see him in my mind’s eye when he entered the sanctuary, went to his favourite pew on the main floor, right side of the pulpit (to Rev Goth’s left), about 6 rows from the front. Every time, he went into that seat – he was always early – he sat on the edge of the pew and leaned his forehead onto his sideways turned right fist and remained in that position for a few minutes. I always assumed he was in prayer. He never spoke to us about this; it just seemed to me to be his humble supplication before God. There are no kneeling benches in Protestant churches as there are in Catholic and Anglican churches and this act it seems was my father’s postural form of embodied contrition and/or reverent respect.

My younger sister, Marnie and I went to Sunday School; Marnie was in classes on the lower floor, I believe. My Sunday ‘school’ was quite unique. Now in high school, I had outgrown conventional sunday schooling; instead, a group of us, teenagers met in an upstairs (balcony level of the sanctuary) room shortly before 11:00 every Sunday during the school year. There might have been 10-15 of us at different times and we had a parent ‘leader’ whose role was to initiate and moderate discussions on any topic – rarely purely religious ones – we chose. To me, it was an alluring way to foster discussions where the bottom lines were listen to and respect each other. I can’t remember any of the topics but I did make friends with several students from different high schools across the city. I fancied myself quite dapper, even resplendent in my brown suit that came complete with 2 pairs of pants when I bought it. I felt it blended perfectly with my brown loafers that my father insisted I shoe-polish every Sunday extracting the wooden shoe-box crafted by my grandfather with its flip-over, hinged lid footrest on the upturned cover and the box itself replete with shoe polish (black and brown), rags, and brushes designated for each colour. Dad had taught me how to tie a Windsor knot in the narrow ties that were in fashion then; I believe I owned exactly one tie. What made those classes/discussions even richer was the coordination of attending Rev Goth’s sermons. Someone would knock on the door as the ongoing service was nearing the time for his sermon. Quietly, we would be ushered, literally, into the balcony area to Rev Goth’s right. Thus was my introduction to and some 5 years of riveted attention to this ‘voice,’ this sermonizer nonpareil.

Very likely, Reverend Goth’s texts and ideas were starting points for our next week’s teen group discussion topics. To me, he brought me into the literature, not only of the Bible or scripture as literature but to theological scholars like his most frequently cited ones such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Paul Tillich, Reinhold Neibuhr, and Karl Barth and likely many others whose names I have forgotten. Rev Goth would teach me/us about their perspectives on religion, society, and cultural connotations along with connections to Biblical passages and precepts. Somehow, Goth’s oratory made meaning for me, meaning about religious precepts, about ‘thinkers,’ about religion seen through a prism of refracted interpretations. For example, one Paul Tillich maxim I have retained is this one, “the opposite of faith is not doubt; it is certainty.” The faith and the faithful always seemed like trite expressions; Protestants were and are supposed to have ‘faith’ and we or I were never quite sure from whence faith was derived – from Raikes-induced attendance, from reading scripture.? If, as Tillich asserted, certainty is the opposite of faith, then I could align with the concept of faith without, lemming-like for me, becoming one of the faithful. That precept was akin to my comparable belief that the opposite of love in not hate; it is fear. Lessons like Tillich’s very likely became discussion points at our Sunday group discussions. For me, they were also my first real engagements with the literature and world of religion, at least the Christian religion. I was hooked, enchanted by Rev Goth and by the larger implications of religion, theology, intellectual literature, and meaning.

And I had lots of religious experience comparatives to those of Metropolitan Goth. When I worked in tobacco during the 60s, my girlfriend, Maureen Clarysse grew up in the Catholic church; often I accompanied Maureen and her family (her father, Roger was the farmer for whom I worked in tobacco harvests) to a small, rural Catholic church. To my delight, the services were conducted almost entirely in Latin, not an uncommon Catholic ecclesiastical practice at the time. I fancied myself quite the Latin scholar, studying the subject every year throughout high school, and focused my attention on self-translating and then, on the drive home, telling the Clarysse family – they had no knowledge of Latin, just ipso facto respected the service components delivered in that language – what I gleaned from their church’s Latin liturgy. At Beck high school, I was a member of the Key Club, a sort of junior Kiwanis club that is actually the oldest and largest student-led service organization for high schoolers. In addition to doing public services like yard-clean-ups throughout the city, we voluntarily attended church services all across different denominations in London. The latter practice was fascinating to me in learning about the different forms of Christian (and Jewish) religions and religious doctrines and practices were celebrated in services. And I constantly measured the various church ministers’ sermons against those of Rev Goth; his were incomparable, in my view.

In many ways, for me Rev Goth was a kind of physical- and voice-embodiment of Mr Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s famous 1899 novella, Heart of Darkness. I was introduced to the narrative in Grade 11 and, although initially resisted by me as a ridiculous story, very quickly the book absolutely fascinated me. Marlow, the protagonist journeys up the African Congo and ultimately connects with Kurtz who has been rapacious gleaning ivory from Africa’s interior and gone mad doing so. I see the novel as apocryphal but more importantly, allegorical – the journey of a man (Marlow) into the centre of his own soul. Kurtz has become a demigod (to the natives) and gone mad. All along the river, Marlow keeps hearing tales about Kurtz’s voice, his power of persuasive speech and, once face-to-face with Kurtz, he quite fittingly likens Kurtz’s bald head to an ivory ball:

The wilderness had patted him [Kurtz] on the head… it had caressed him and—lo!—he had withered; it had taken him, loved him, embraced him, got into his veins, consumed his flesh, and sealed his soul to its own by the inconceivable ceremonies of some devilish initiation

Through much perhaps subconscious extrapolation on my part, Goth and his voice were representations or echoes of my study of and about Kurtz. As Marlow was enchanted by Kurtz, I was charmed, as enraptured by Goth as Marlow was by “the snake [Congo River) [that] had charmed me” in the river’s pull toward Kurtz. I am aware of three of Rev Goth’s sermons that were recorded and kept in Metropolitan’s archives. One of those is his 4 February 1973 sermon, The Call of the Deep. When I found and listened to this recording while researching information for this blog, Goth’s voice came rushing back to me even though hearing versus hearing-and-seeing him are quite different for me. And I can’t help but notice now just how eerily and coincidentally similar Goth’s vocal timbre is to that of Marlon Brando cum Colonel Kurtz’s tonality in Apocalypse Now, a Vietnam war revamp of Heart of Darkness. Dare I say there is a goth-ic similarity?

There was so much to the allure of Metropolitan even in its literal meaning as of or belonging to a mother city {from the Greek words mētēr (mother) and polis (city)}. For example, my older sister Sandi was a soprano member of the church choir during the 1960s. Studying vocal music at Western, she was frequently the service’s soloist. It was stunning to me to watch-listen to her sing – my sister – clad in her light-blue choir gown singing in front of everyone at Metropolitan. Not kosher to do so, I always wished the congregation would clap when she finished her solos. Sandi’s boyfriend and future husband, Paul Mennill was a choir member as well. Reverend Goth married them in 1967 and Sandi told me recently that she was baptized also by Goth. It amused me, sitting in the balcony above the choir loft and observing Sandi, book in her lap, reading or studying during Rev Goth’s sermons. Perhaps she was multi-tasking; I could not imagine doing anything else but listen to Goth. For a couple of years, after I became a licensed driver, my ‘job’ was to drive Sandi to choir rehearsal preceding the service and return home to chauffeur Dad and Marnie to the service itself. On the family trip home post-service we often stopped to pick up a half-gallon carton (wax-coated and very common then) of ice cream from – I believe – the Parkview Dairy Bar not far from our home.

Ice cream in a half-gallon box in 1960s simple chocolate or vanilla choice days

Reverend Goth’s voice resonated in me for years as did all of my Sunday School upbringing. Visiting friends in North Bay once, I attended a Baptist church service and heard a Reverend Moffat – subsequently, I called him the muffet when recalling the experience – get red-faced, neck veins popping while delivering a sermon called ‘please don’t eat all the raisins.’ The sermon was about his growing up during the Second World War and having to treasure treats like succulent raisins. I retain no idea of how he connected his text to religion. But what struck me was his speaking passion; it was impressive, illuminating in its own right. Delivering speeches became a focus for me. When Reverend Goth was away, Metropolitan’s sermons were provided by the church’s other – associate – minister, Reverend Anne Graham. She was a delightful person, kind and gifted with a warm handshake and full eye contact given to us as we were greeted by her in the narthex exiting the church after the service (I have no memory of Reverend Goth shaking hands in that area nor, actually of ever speaking directly to/with him). As a speaker, Reverend Graham was so-so and in fairness, Reverend Goth was a hard act to follow. Because of Goth’s speaking prowess, as an Undergraduate student I became focused on observing professors style of delivery – how they taught, how they spoke, and how they did or did not engage with us/me. Many of my profs in Phys Ed (now Kinesiology) were stunning teachers and in contrast others seemed bored or lacking any formal teacher training; some profs merely read verbatim, the whole lecture from the textbook and called that teaching and I was quite incensed fully aware that I could read when what I wanted was meaning, delivery, and discussion. I did what was called a ‘double major’ Honors’ degree and my other major was English literature. Profs in that discipline had a distinct advantage in that they always taught about and with good literature and I would listen to anything and anyone about good fiction, essays, and poetry especially from the literary canon (the benchmarks of literary quality).

Concomitantly, there is a literary quality to Christian religion and worship, its liturgy or the structured, public way people worship, involving set prayers, rituals, songs, and readings that guide congregations’ collective service. Rituals and routines were a major component of my attraction to church or church-ness. Communion, for example, partaking of the bread and wine, metaphorically or symbolically the body and blood of Christ, was and is sacred – termed, in fact, one of the sacraments – in the Christian religion. The altar from which the pre-prepared wine-that-is-really-grape-juice and small squares of bread often bears the communion inscription carved on its front, Do this in remembrance of Me, words echoed by the minister in delivering the sacraments. The silver trays, like this one…

were stacked on the altar along with silver plates of bread squares. After serving themself, the minister served the ushers who, in turn, carried the bread and wine to be passed along the pews to be taken and ingested by parishioners. The glass vials of grape juice were very small and had to be extracted gingerly and carefully from their tray-holder; once consumed, the backs of the pews had fixed slots, like the one below, into which the empty glasses could be stored. The clicking of those communion glasses being inserted into their resting slots reverberated for several minutes in the otherwise hushed ceremony.

I liked the ritual; it felt like an honouring of the church even if the literal notion of the body-and-blood went beyond my ability to accept. During the delivery of the sacraments, the organist often played a very softened background musical piece. Often one of the most famous hymns, Praise God from whom all blessings flow would be sung by the whole congregation normally preceding communion; it is difficult not to know most of the words to that hymn to most regular church-goers. And so too do the words of the Apostles Creed, the succinct doxology summarizing Christian beliefs, reverberate for me, recited so often in services:

I believe in God,

the Father almighty,

Creator of heaven and earth,

and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord,

who was conceived by the Holy Spirit,

born of the Virgin Mary,

suffered under Pontius Pilate,

was crucified, died and was buried;

he descended into hell;

on the third day he rose again from the dead;

he ascended into heaven,

and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty;

from there he will come to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and life everlasting.

Amen.

I knew it by heart, still do, and once again, it seemed to me to be the thing to do-recite than it was any confirmation of my belief system. Its title, Apostles’ Creed is attributed to Jesus’ 12 apostles or disciples famously depicted in the painting of the Last Supper, the meal partaken by them the night before His crucifixion:

This is a rendering of perhaps one of the most famous paintings in the western world, Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece, his rendering of the event. I remain more interested in that representation than whether or not such an incident ever occurred. da Vinci’s Last Supper is the painter’s still-capture of the prophetic moment Jesus announced to his 12 apostles that one of them (Judas, not-named as the Biblical story is told) would betray him, turn him over to the priestly authorities who would crucify him, and the disciples react in shock. Thus the painting etches both the significance and the ‘reality’ of the Christian belief system centering on the Son of God – it reifies or bolsters and perhaps reinforces Christian faith.

Biblical literalism never captured my thoughts, ideas, or beliefs about organized religion. It never mattered to me whether Biblical stories, Old Testament or New Testament were/are true. Did Moses actually receive the Ten Commandment tablets from God on Mount Sinai? Did Moses ever part the Red Sea? My father often told the only religion-motif joke I ever heard from him when he said, ‘and the Lord said to Moses, come forth…but Moses came fifth and lost the race.’ Dad was a quarter-mile sprinter in his youth and very much enjoyed that quip devoid of any sense that it might be perceived as slightly sacrilegious. Did Adam and Eve ever exist as the first humans named on the Old Testament? The couple, it is said, were placed in the Garden of Eden and disobeyed God by eating forbidden fruit – the apple – from the Tree of Knowledge leading to their expulsion (the famous “Fall of Man”) and introducing sin and mortality into the world. It just doesn’t matter if these things actually happened; it is the intention behind the Biblical stories and their impact on belief systems that interests me. They are a way of humans looking at themselves through the mirror one form of religion. To me, they are not true stories; they are stories of truths that enable Christians to perceive and grasp their beliefs and integrate those beliefs and stories into their worship.

In the same vein, there are so many exquisitely written (and re-written) Biblical passages that, for me, go well beyond any religion as important precepts for living life with humanity and respect. For example, the famous Sermon on the Mount, ostensibly delivered by Jesus, renders us the Beatitudes, 8 blessings that embody espoused Christian values of kindness, respect, and equity:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God. Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Matthew 5: verses 3-10, King James version

Christian or agnostic or atheistic, these are clearly expressed ways of perceiving humanity in all its dignity and completeness. So too is there a comfort in the Old Testament’s 23rd Psalm, commonly referred to as The Lord is My Shepherd:

The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters. He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me. Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

23rd Psalm, King James’ version

Attributed to Kind David, Israel’s famous warrior king, and often called the Psalm of David, the comfort for me is in the Psalm’s language and imagery…the softness of ‘shepherd,’ ‘pastures,’ ‘paths,’ even the ‘shadow of death’ has a mellow quality.

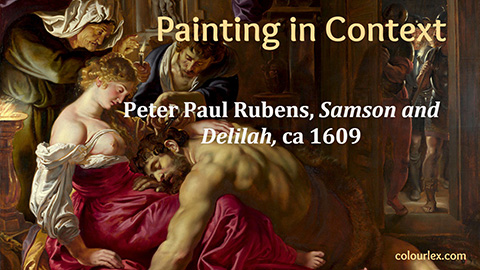

Biblical stories mesmerized me – in the book of Judges, Samson was preternaturally strong, his secret prowess was in his uncut hair and he was betrayed for money by his lover/wife Delilah. Captured, chained, blinded, and hair shaven, Samson summons his strength and brings down the temple of an ancient peoples, the Philistines. The story resonates with meaning even in the name-word, Samson synonymous still with the concept of strength and in a multitude of well known classic works of exquisite art like this one:

Embedded in the story are all manner of implications about strength of conviction/belief, betrayal, the ‘sin’ of lust etc. Finally, my favourite story is that of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego from the Book of Daniel (Chapter 3). These three young Jewish men refused to bow to and worship a golden idol. As punishment, Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar had them thrown into a fiery furnace; however, God protected them because of their faith and they emerged unharmed. Again, the story has all manner of connotations about worship, faith, punishment in the fiery furnace of hell, false gods etc. Why I like it is purely sonorific, the richness of the names Meshach (me-shack), Shadrach (shad-rack), Abednego (a-bed-knee-go), and Nebuchadnezzar (ne-boo-kad-nezz-er) – all euphonous, pleasing, even melodious, the latter literally so as rendered by jazz and blues’ great, Louis Armstrong’s “Shadrack” first recorded in 1938. Just being able to say the 4 names is still fun for me.

Equally enchanting to me is the sheer architecture of places of worship, consecrated structures that are literal testaments for the faithful…

The interior of the Synagogue, completed in 1882, Florence, Italy

Siena Cathedral, Siena, Italy; constructed in the 13th century

These and many, many other mosques, churches, synagogues, and magnificent places of worship around the world are majestic buildings that inspire (so exquisite they put your breath back in, not take it away) beholders regardless of their beliefs.

At some point in the late 1960s, I began to think about a career in the ministry lured mostly by the prospect of speaking from the pulpit, aping Reverend Goth. Those thoughts were buttressed by my mentor’s teachings about the history of the body in western culture. Professor Jack Fairs – see my blog honouring him, Jack – was erudite, funny, devilish, and meticulous in his delivery of lectures. Technically, Jack was not a good teacher – he wandered from his lessons; he read from his notes; he told jokes; filled blackboards with information; gave us reams of ditto-printed quotations and diagrams. And yet, he was absolutely, indefatigably engaging! What particularly inspired me was his carefully researched connections of religion to cultural views of the body. Humankind, he opined, were souls for mysterious, accidental reasons imprisoned in a body – the ghosts rose from my Centralia graveyard. He took us/me through centuries of examples of how the Christian church and theologians disparaged the body in favour of the divinity attached to the soul; after all, it was the soul that went to heaven, the body died. Jack reinvigorated my allure to the complex, multifaceted aspects of organized religion that Reverend Goth had first instilled in me.

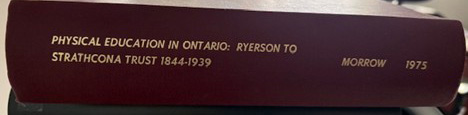

Jack’s teaching about the body and religion in western culture prompted me to ask questions about how that had played out in Canada, a geographical area rarely mentioned by Jack. By the time I started my doctoral dissertation at the University of Alberta, I was clear about my topic of choice, Reverend Adolphus Egerton Ryerson.

My completed 408-page dissertation in hard copy; full version here

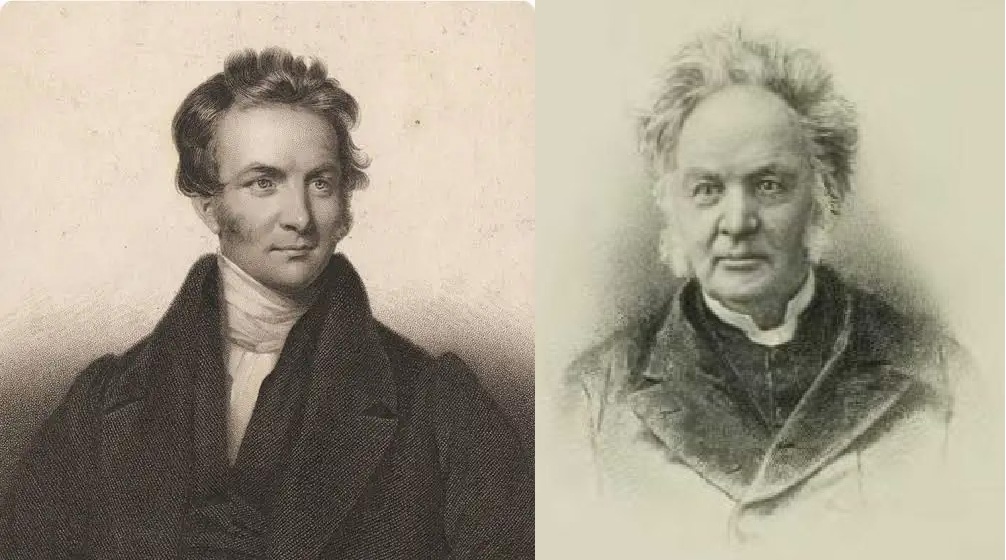

Ryerson is credited as the founder of Ontario’s public education system and my particular focus was on his impact in creating and instilling curricular physical education in those schools. Prior to becoming the province’s first Superintendent (now Minister) of Education (1844 to 1876 was his term of office), Ryerson had served his first occupation as Methodist minister. Methodism is a Protestant Christian tradition that began in the 18th-century Church of England as a reform movement led by John Wesley; it emphasized personal holiness, disciplined living, evangelism, and social service. It evolved into distinct denominations like the United Church. Metropolitan was called First Methodist Church until it was renamed 1n 1925 in becoming part of the United Church of Canada. My knowledge of Ryerson stemmed from the fact that he was born in 1803 in Charlotteville, then a hamlet in Norfolk county not far from where my father and his parents’ family lived. Port Ryerse, a reasonably well known Lake Erie fishing village near Port Dover visited often when I was young, was named after the Ryerson family:

Egerton Ryerson in his saddle bag preacher prime (1830s) and in 1880, 2 years before his death on the right

My initial attraction to Ryerson stemmed from reading about his first occupation as a “saddle bag preacher,” that is, an itinerant Methodist preacher beginning at 22 years of age. It was a kind of missionary post or occupation and he was assigned to a circuit near York (now Toronto) which took him 4 weeks to cover on horseback and by foot. During each month, he was expected to conduct 20-30 church services in addition to personal visits. Roadways were in extremely poor condition during the 1830s and 1840s and combined with the hardships of weather, seasonal variations etc made me infer he was a man of physical strength and considerable religious conviction. My finding was that Ryerson was an ascetic – he lived frugally and I imagined I would have enjoyed his saddle-bag life if only for its physically taxing toll. I almost immediately equated Ryerson-the-minister with the lyrics and sentiments of the song, Reverend Mr Black (Beach Boys, released in 1963) especially its first verse:

It just seemed like such a rhapsodic and soulful encapsulation of Ryerson and the more I read about him in my dissertation research, the more I felt like I too could be a modern circuit rider, not literally but definitely idealistically. Ryerson was an embodiment of the Protestant work ethic, a faith-based concept espousing the values of discipline, diligence, and frugality, denigrating idleness (the devil finds work for idle hands etc). Ryerson wrote:

…I did more than an ordinary day’s work, that it might show how industrious instead of lazy, as some have said, religion made a person. I studied between three and six o’clock in the morning, carried a book in my pocket during the day to improve odd moments by reading reading or learning, and then reviewed my studies aloud while walking out in the evening.

A.E. Ryerson, The Story of My Life, 1883, pp. 342-3.

Ryerson’s father was Anglican, his mother, Methodist and her influence on her six sons must have been considerable because 5 of them became Methodist preachers, religious pioneers of the Canadian wilderness. Historian C.B. Sissons was Egerton’s biographer, penning, literally, Egerton Ryerson: His Life and Letters (1937, Vol 1 and 1947 Vol 2), the tomes testament to Ryerson’s prolific writing. As much as his circuit rider career appealed to me, it was another collection of letters from 1859 to 1881 published as, My Dearest Sophie: Letters from Egerton Ryerson to his Daughter (edited by Sissons) that caught my attention and I read those letters and Sissons’ editing cover-to-cover. Interestingly, the book is now available in a 2021 format, hailed at its selling source as “This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it”:

My reading was in its earliest format and it was as though Ryerson revealed his innermost, unvarnished thoughts about education, religion, life, children, sports, and politics. There was an impatience and intolerance about Ryerson. The founder of Ryerson Press and with Ryerson University (now Toronto Metropolitan – coincidence? – University) named after him has been brandished with the notion of being an architect of the appalling national Indian residential school system. A statue of him was erected in the late 1880s at the Education Department buildings and subsequently moved to the Ryerson campus mid 20th century, cleaned annually by students with toothbrushes as an initiation ceremony:

Ryerson statue, circa 2005 defiled, destroyed, and thrown into Toronto Harbour in 2021

The destruction of the statue and the renaming of the university were coincident with the horrific discovery of the buried remains of children from residential school grounds across the country. My knowledge of his involvement in the residential school movement was that he was aware of its development in the seeds of those schools during his tenure as Superintendent but not involved in either the founding or running of that system; in fact, he died, I believe, the year before the schools were created federally in 1883. Ryerson, no different than most Christian ministers and educators of his time was evangelical in his perspective and was well aware of the issues facing Indigenous peoples. More information on Ryerson’s prolific writings, public and professional life, and his role re the residential schools is very well covered and documented in this Wikipedia posting.

My study of Ryerson was the culmination of my various exposures to Protestant religion to that point in time. Had I not found immediate employment as a university professor the year before I completed my doctoral dissertation in 1974, I might well have entered the ministry, or, at least applied to do so. My attendance at church waned in the early to mid 1970s. By the late 1970s, living in north London, we elected to attend Siloam United Church, a small rural-based church then located at the northeast corner of Highbury Avenue and Fanshawe Park Road:

Siloam United Church, circa 1980; it was opened as the Siloam Methodist Church in 1892

My interest in Siloam was rooted in its history as a Methodist-founded organization dating back to the early to mid-19th century and directly connected to the labour law movement and reform history of the British Tolpuddle martyrs. The Tolpuddle story can be gleaned at this site as well as from this narrated video connecting the martyrs to Siloam. My lure to Siloam was related to the fact that 5 of the 6 ‘martyrs’ emigrated to the London area and were responsible for the establishment of the small church community that became Siloam. The name Siloam is taken from the name given to a pool on the edge

of Jerusalem which is mentioned several times in the Old Testament; literally it means ‘artificially fed.’ In the New Testament (John 9), one of the miracles attributed to Christ was an incident where Jesus told a blind man to wash in the pool of Siloam; the man does so, regains his sight and this act is perceived as one illustrating ‘blind’ faith, spiritual in/sight, and divine power.

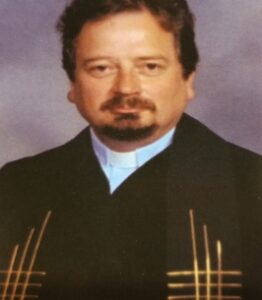

My personal involvement in the Siloam church was one of family attendance at first and then one of service to that church, the latter the closest I came to any ministerial leanings I entertained. Siloam was very small in size and its community was welcoming and friendly. I remember the first minister I encountered there, Rev Ron Pocklington, affable, light brown-bearded, bespectacled, with an infectious chuckle. His sermons fitted his personality – straightforward, Biblically-based, and reverent. What always amused me was for every hymn that was sung at Sunday services, watching him move furtively from the very small pulpit, up 2 or 3 steps and into the choir loft to take his place in the tenor section of the choir and then return delicately on the precarious tiny route to his pulpit. By far, my most personal connection to a minister was to/with my friend, Reverend Douglas Hallman (1948-2019):

While not the most flattering image of Doug, it does capture his mustachioed, soul-patched wry smile, cherub-like visage, and ministerial robes. In the latter regard, I remember his customary, sharp robes at Siloam – dark blue, priestly top, white clerical collar, and very prominent, small (2.5 by 1.5 inches, perhaps) wooden cross on his chest, suspended from a black cord around his neck. Doug succeeded Ron Pocklington at Siloam and Doug served` there from 1981 to 1986. Interestingly, Doug was born Walter Joseph Hazlett in Nova Scotia. When he was 9 or 10, he was adopted by the Hallman family and chose the Christian names, Douglas Ward.

Just before Doug was appointed to Siloam, I was nominated and elected to chair the church’s official board, the primary governing body of every United Church local pastoral charge; the board is/was responsible for the oversight of the religious and secular operations. It was initially a 3-year term and I was re-elected for a second term. At the time of my selection, I had just been appointed as my Faculty’s Undergraduate chairpersonship and in many ways, I saw the Siloam position as a complementary administrative position – administering at the university and ad-ministering – the closest approximation to the ministry that I ever achieved – at Siloam. As the chair of the ministerial selection committee that brought Doug to London, it was my purview to greet him and his wife, Dianne at the manse. Most Protestant churches provide a house (manse) for the minister and their family. Siloam’s manse was more than a century old – it pre-dated the church building – when Doug and Dianne moved into the house and I remember that congregation volunteers spent many weekends cleaning up the yard, painting the interior, installing a new roof and other almost patchwork renovations in preparation for the new minister. Upgrades and all, it was almost an ascetic experience living in that house, cold and damp in winters and roasting hot in summers.

Over the next five years, I came to know Doug very well, considered him a close friend as well as a minister. We were the same age, he one year older, almost exactly so as his birthday was July 28th, mine the 27th. And he knew about my ecclesiastical upbringing and soft-bent toward the ministry. I think in many ways, Doug was kind of a glimpse into what I might have done had I chosen the ministry though his talents were far greater than mine. Doug was musically gifted as a classical pianist and occasionally, modest by nature, he would play pieces for his congregation outside of church service hours. He related to me that he attributed his ‘call’ to the ministry as a literal one listening to a radio program – I have forgotten the specific details and loved the down-to-earthness of his calling – and he just knew he needed to devote himself to ‘the cloth.’ He was deft in his ability to conduct church services and his sermons were carefully composed often experiencing what he called “Saturday Night Fever,” a loose allusion to the 1977 musical, because of the weekly angst he went through figuratively – maybe literally – praying his words would have meaning and be well received. For me, they always did. The only beef about his job I ever heard him utter was his mild disdain for what he termed “Christmas and Easter Christians” – those Christians whose only connection to the church was attendance at services on those two occasions, no other visible homage to church; I believe he viewed them as somewhat hypocritical, Christian in name only. I liked Doug, admired him tremendously. I retain many memories about our friendship and his nuances from the pulpit. In the latter regard, the one that stands out indelibly is his re-enactment verse, Little Cabin in the Woods. It was a verse that he sang and recited with all manner of gesticulations to children transitioning during the service from the sanctuary to Sunday School:

In a cabin in the woods

Little man by the window stood

Saw a rabbit hopping by

Knocking at his door

(Frightened as can be)

“Help me, help me, help,” he said

Or the hunter will shoot me dead”

“Little rabbit, come inside,

Safely to abide.”

Itty bitty cabin in the woods

Itty bitty man by the window stood

Saw a rabbit hopping by

Knocking at his door

(Frightened as can be)

“Help me, help me, help,” he said

’fore the hunter shoots me dead”

“Come little rabbit, come with me

Happy we will be.”

Great big cabin in the woods

Great big man by the window stood

Saw a rabbit hopping by

Knocking at his door

(Frightened as can be)

“Help me, help me, help,” he said

Or the hunter will shoot me dead”

“Come little rabbit, come inside,

Safely you may hide.”

For the life of me, I cannot remember Doug’s point but I was always amused the multiple times he enacted the verse by his affective tone and the actions – mock-rifle aimed and waving, Doug grinning unabashedly at ‘Or the hunter will shoot me dead.’ This 2019 video of the children’s verse, its lyrics and actions is so reminiscent of Doug’s rendition. Looking at the words now, I perceive its implications for safety, kindness, and compassion, all values I know Doug felt and espoused. At some point either during Reverend Hallman’s ministry at Siloam, I first encountered the contemporary (composed in 1963 and included in the United Church hymnal or hymn book) hymn, Lord of the Dance with its vibrant, up-beat tempo that can be heard here. It is so far removed from the drone-and-dirge of traditional hymns, so much more celebratory in its invitation to dance one’s beliefs:

Dance, then, wherever you may be;

I am the Lord of the Dance, said he.

And I’ll lead you all wherever you may be,

And I’ll lead you all in the dance, said he

It just contrasts so starkly from the hymn-singing we did at my grandparents’ church, Salem United or at Metropolitan. At the same time, in revisiting this blog, I am aware that its third verse might be interpreted as anti-Semitic, blaming the Jews for the death of Christ.

My ‘gift’ to Doug when he arrived in London was to entice him to go for a run with me. He was not a runner and I was hooked on long-distance runs and marathons. Intending to run a couple of miles at most, Doug insisted that we keep going and we ended up completing 10 miles out in the country north of the church on a warm July (I think) day, an incredible accomplishment, if not foolhardy in hindsight. Doug also had an intellectual bent; he was a thinker regarding all kinds of topics. I reconnected with him sometime around 2008 when he invited me to join a discussion group studying the meaning of scriptures and other religious’ texts. I attended a few of the discussions but was not drawn to them. Two years later, 2010, I saw an advertisement for a Brock University philosophy society reunion. One of the featured speakers was Doug. He had lived in that region for a period of time and in some ways kind of ‘accidented’ into the engagement. Some years before the Brock society meeting, someone asked Doug to speak about the religious story-line authenticity of the the popular novel, The Da Vinci Code (2003, Dan Brown). As the ad described his connection to the novel:

Hallman has given numerous talks and media interviews and eventually wrote a book about the Dan Brown novel, a fictional yarn about Mary Magdalene being the wife of Jesus and mother of his child. It wasn’t an association the Brock alumnus (MA ’94) sought out at first. The task of explaining the novel’s facts and fictions was more or less assigned to him when the Niagara Institute of Faith and Culture asked him to speak on the topic.

“It got big attendance because the novel had just been released. People from the whole area attended,” Hallman recalled. “By the time I had finished with all the invited talks, I had about 600 pages. I’m not sure I’d have read the book if I hadn’t been invited to speak on it.”

Looking ever so erudite and still chubby, cherub-cheeked for the 2010 event…

I wish I had seen the posting earlier than post-event…I might have attended just to hear him. My understanding is that Doug compiled his research into a roughly 600-page manuscript or document, self-published it and privately circulated the book in which he sought to analyze the theological and historical claims of the novel. Apparently, Doug produced substantial material on the subject and it was used mostly for his lectures, interviews, and presentations rather than being published through a mainstream commercial publisher. Doug reached a milestone in 2018 and was recognized for his 40 years of service to the ministry. Sadly, in April of 2019, about a year after re-marrying, he succumbed to complications surrounding prostate cancer. Graciously, fully aware of our friendship, Dianne contacted me with the news of his passing along with a link to his obituary. Douglas Hallman literally wore his faith and his religion on his vestments’ sleeves. Friend first and foremost, he was in many ways my last/ing connection to organized religion and the embers or ashes of any aspirations I might have entertained for the ministry.

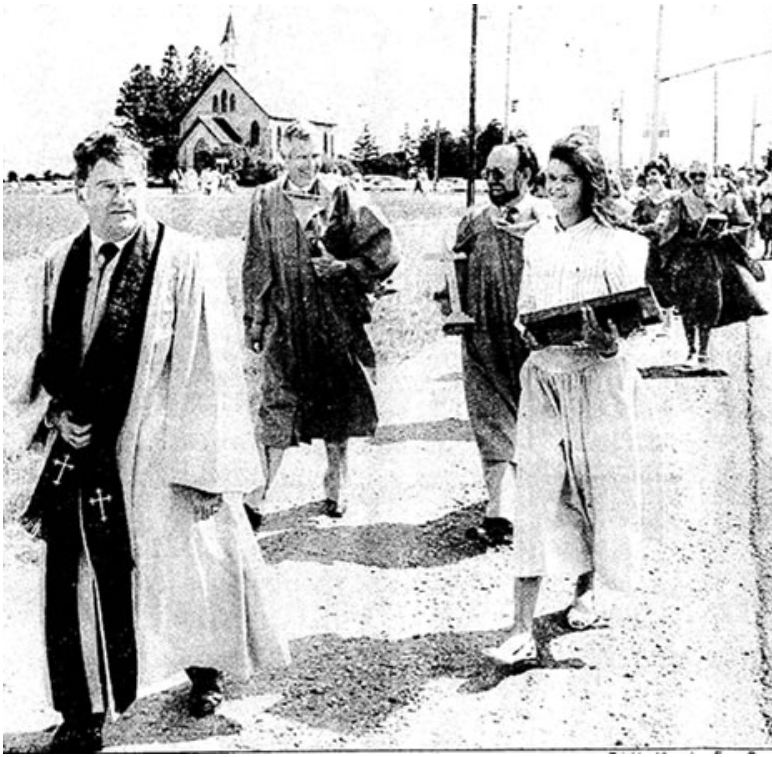

When Doug left Siloam, I had one year remaining as chair of its official board. Its new minister, Reverend Ken Martin I remember as quiet in demeanour, deep-set eyes, curly salt-and-pepper hair and I had some connections with him professionally and personally during that year especially through our involvement in acquiring land and planning for the construction of a new church building a few hundred meters west of the old church on Fanshawe. On 26 June 1988 Rev Martin conducted the last service at the old church then he led the whole congregation walked down the road to the new building and completed the day’s service of worship:

Newspaper sketch of Rev Martin leading the congregation to the new building

Siloam United Church circa 2000

My tenure at Siloam continued sporadically into the early 1990s. Our sons attended Sunday School there; however, it seemed all of our interest in church attendance waned, certainly mine did. What replaced my involvement with organized religion was my involvement with a different community called the Shalom community. Lawrence – I knew him as Laurie – Stibbards and his wife Joy Davey built the community in London. Lawrence, a minister and family therapist was best known to me as a therapist and retreat leader and I attended many of his (and Joy’s) retreats held at The Schoolhouse – an aging facility that had been a school house in decades past – near Brussels, Ontario. For me, there was a spirituality to those retreats that I had not felt or experienced within the confines of religion.

At those retreats and in therapy with Lawrence, I learned so much about what I came to see as a much wider perspective on spirituality than I had gleaned within church walls. I read widely within and about the Gnostic Gospels and Gnosticism, all deemed heretical by many Christian-focused scholars. Even more, I read voraciously anything I could about Jungian psychology and that perspective coincided far more closely with what I believed about human existence. In particular, Jungian psychologist Marion Woodman was an inspiration to me; her book The Pregnant Virgin was/is replete with Jungian inferences and examples about the feminine principle in life. One line stands out from that little book: “It won’t work if you stand in front of a flower and yell, Bloom!” It was my absolute privilege to nominate Marion for an Honorary Doctorate degree from Western University and even more of an honour to introduce her to Convocation when her doctorate was bestowed on her on 5 June 1995. The imp in me met the imp in her when, to assuage her nervousness, I had everyone in the entire Alumni Hall ceremony stand up and wiggle their whole body as a dog would shake water from themself in emerging from a swim; it was an exercise Marion did in leading her professional retreats. Having academics – the stage assembly especially – do so was a memory I treasure and Marion beamed during the shake-down.

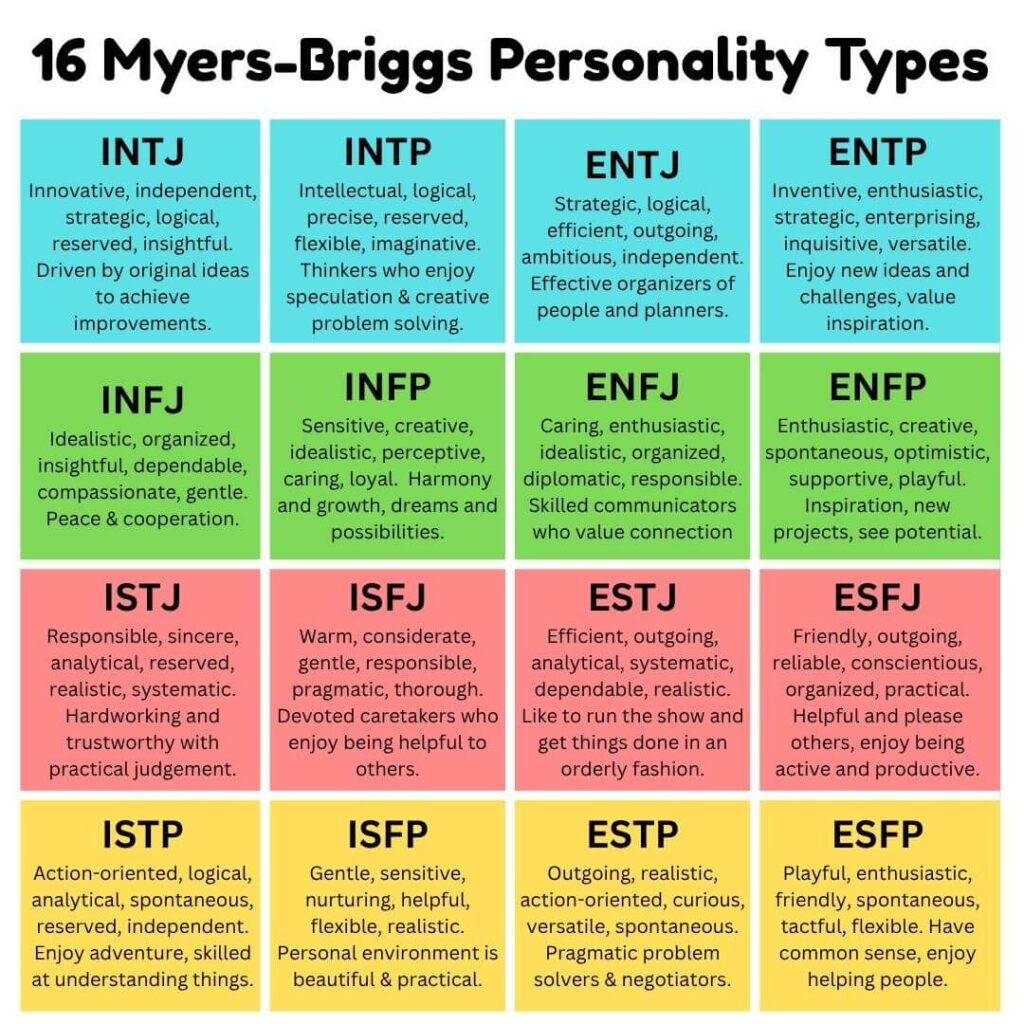

More generally in terms of Jungian psychology, I was drawn to Jung’s Man and His Symbols (1961) as insights that delve into and un-mask the symbols – like circle, snake, water, tree etc. – we live with, often unaware in ordinary life to the felt-reality of the collective unconscious, archetypes, the shadow, projection, dreams and dreaming, individuation, and personality types, the latter coinciding with my previous learnings about and training in using the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) to understand and elucidate 16 distinct personality-based perspectives and typified behaviours:

The 16 MBTI Personality Type chart; my own preference is ENFP

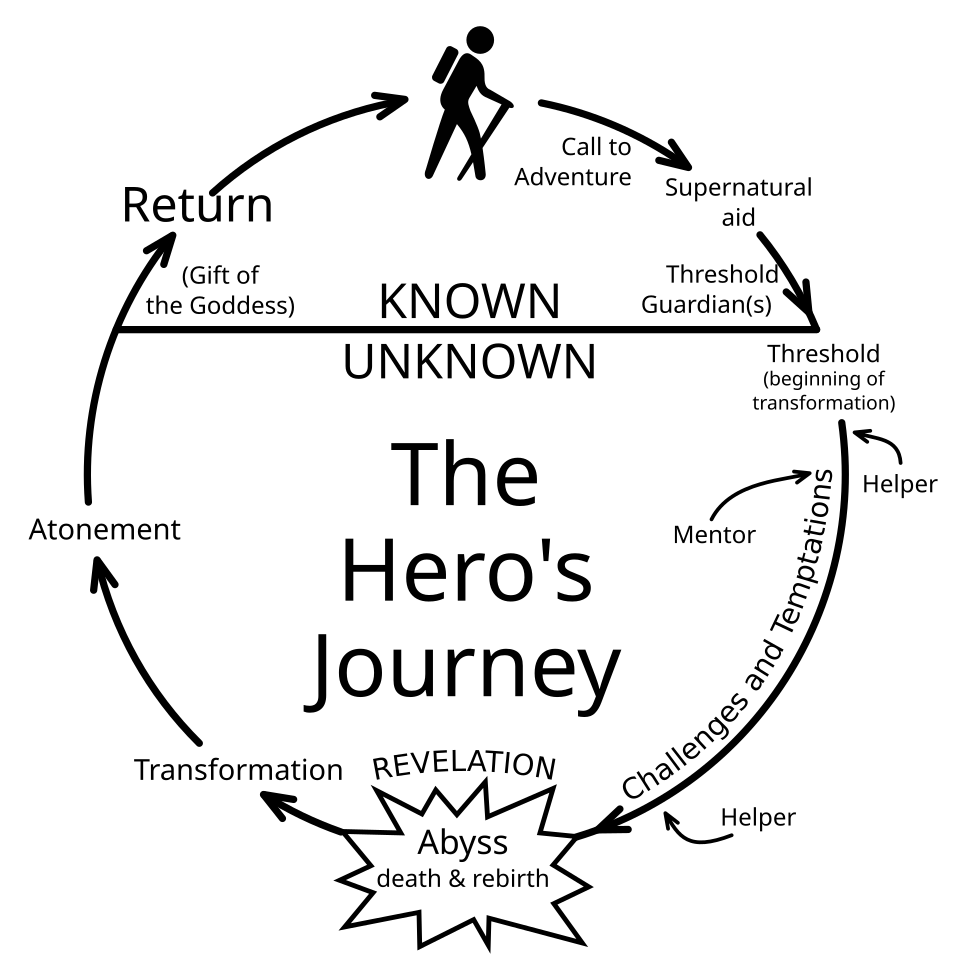

In the same vein, I devoured Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces published in 1949 – my year of birth. The text examines the common themes and archetypes found in myths worldwide; Campbell argues that these stories reflect fundamental human experiences and desires. My whole career was predicated on researching and writing stories mostly revolving around sport history. Stories, fiction or non-fiction were always stories of truth if not “true” stories. The basic story-line of any narrative – the ‘heroic’ journey, or the monomyth, as Campbell termed it – is departure from existing location or way of being, initiation or ordeal entering into a new way of being or learning, and then return to the original way of being/location to integrate insights or new ways into continued life. Conceptually, the monomyth unfolds as . . .

To me, this paradigm made and makes more sense as a universal principle – even, as sacrilegious as some might perceive it – applied to the story of Christ as one of mythic proportion rather than literally true. It is, for me, the fabric of humanity, the path we all ‘walk’ in life’s journey, each of us our own myth. When I taught university sport literature courses, as I did for 25 years, the departure-initiation-return framework was a constant refrain in our discussions about any novel or story.

Thus, myths and archetypes explored, unfolded, and made rich in Campbell’s works (his 4-volume Historical Atlas of World Mythology has been in my library for more than 25 years) felt like I had arrived – my ‘return’ after Jungian initiation? – back/at my own beliefs. I treasure and wholeheartedly believe in Robert Fulghum’s credo and ‘storyteller’s creed’

I believe that imagination is stronger than knowledge-

That myth is more potent than history.

I believe that dreams are more powerful than facts-

That hope always triumphs over experience-

~ Robert Fulghum, All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten, emphasis mine

Myth is often equated with the notion of a falsehood, a widely held but untrue belief. How often do we hear, “oh, that’s just a myth!” My view is myth is much more “potent” and of far greater significance than its untrue connotation. I see myth as

The system of basic metaphors, images, stories that informs the perceptions, memories, & aspirations of a people

So we get, for example, the myth of Sisyphus – the god-man sentenced for eternity to push a huge bolder up a hill only to have the bolder roll back down to the bottom and he having to start his herculean task once more never ever getting to the summit to complete his task. Clearly, that myth is literally not true but its truth can be understood by anyone who has ever attempted a task that is overwhelming and seemingly endless – a Sisyphean task. In many respects, I perceive Biblical stories as myths – Samson and Delilah mentioned above or the burning bush of God delivering the 10 commandments to Moses or Jesus feeding the multitude, 5000 people from 5 loaves of bread and 2 fish (the latter described in Matthew 14: 13-21). It just does not matter to me whether these events actually happened, it’s the meaning of the stories and the importance attached to the stories that are important.

Mystics and mysticism stem from the concept of myths. Their writings illuminated my imagination and passion for learning something much deeper, to me, than organized religion. I read from works by and about Meister Eckhart, 13th century Catholic priest, theologian, philosopher, and mystic who famously, eloquently, and elegantly said, “If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough.” Hildegard of Bingen, 12th century abbess, writer, and ‘mystic,’ and Julian of Norwich, the 14th century English anchoress (a kind of religious hermit) best known for her writing Revelations of Divine Love, one of the earliest English language works written by a woman were eye-opening for me. The 13th century Sufi mystic, Jalaluddin Rumi crafted poems that oozed spiritual connection and a divinity that was far more universal than any single ‘right’ religion. I remain a staunch admirer of his poetry, this little verse exemplary of his works and a favourite of mine:

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

There is a field. I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

The world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase each other

Doesn’t make any sense.

The first two lines resonate/d more for me than any ideas of sin and sinning from Christian religion.

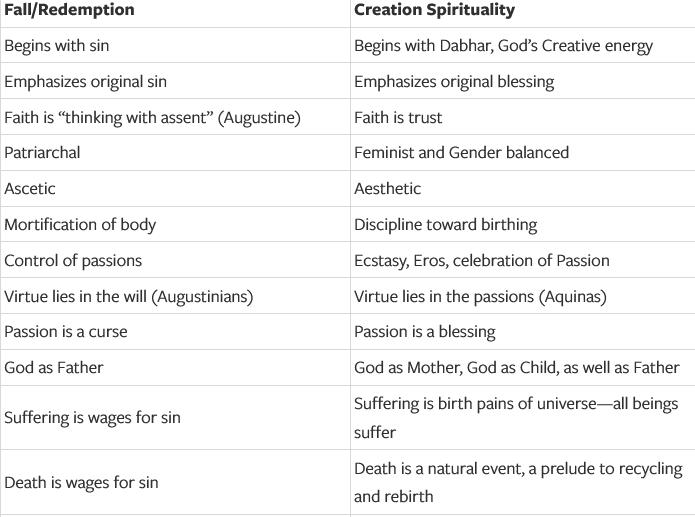

Somewhere along that path of ingesting meaningful texts, Laurie Stibbards introduced me to the works of Matthew Fox. Fox is/was a Dominican (Catholic) friar who was silenced and later expelled by the Vatican for his progressive views before joining the Episcopal Church. By far Fox’s most inspiring text, to me, was his book, Original Blessing; A Primer in Creation Spirituality (1983). In essence, instead of Christianity’s incipient insistence that every human is born in original sin stemming from the “fall” of Adam and a life of redemption-seeking, spiritual theologian Fox espouses the exact opposite – humans are born/created in original blessing. Some of the contrasts between the Biblical/Christian Fall/Redemption theology and that of Creation Spirituality are these:

Extracted from Fox’s website as a sample of his more complete table of contrasts

I was thrilled that Fox was basically a heretic, in the eyes of conventional, Catholic religion. Even more, his ideas and the constructs of Original Blessing were so informative and all-encompassing for me and I immersed myself in Fox’s writings and their more down-to-earth and realistic ideas about spirituality in a more universal form than any sect of organized religion. I think of how many times in my life I literally recited the Christian Lord’s Prayer, “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name, thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread…” (Matthew 6: 9-13). For me, it became a recitation and I rarely connected it with reverence, the words just did not reverberate. Then, while looking at some of Fox’s other writings – The Coming of the Cosmic Christ, many of his books on mystics like Eckhart, and One River, Many Wells – I happened upon a version of the Lord’s prayer translated from the original Aramaic or language spoken around the start of the Christian era 2000+ years ago:

O Thou, the breath of Life, your Name shines everywhere!

Release a space to plant your Presence here.

Envision your “I Can” now.

Embody your desire in every light and form.

Grow through us this moment’s bread and wisdom.

Untie the knots of failure binding us, as we release the strands we hold of others’ faults…

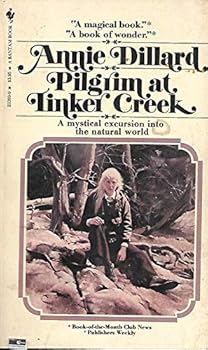

Perhaps I would have memorized these words as platitudes similar to my recitations of the common version of the Lord’s prayer. And yet ‘breath of Life’ seems so much more reverent than ‘Our Father’ and the image of a male, bearded, all-knowing God sitting on heaven’s throne and the standard prayer’s over-emphasis on sin, temptation, trespasses, and the evil-devil. I regard Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

as the closest modern book approximating the spiritual writings of the ancient mystics. Her exploration of nature and ruminations on life – like the one below – are profound and mind-magnetizing:

Our life is a faint tracing on the surface of mystery, like the idle curved tunnels of leaf miners on the face of a leaf. We must somehow take a wider view, look at the whole landscape, really see it, and describe what’s going on here. Then we can at least wail the right question into the swaddling band of darkness, or, if it comes to that, choir the proper praise.

Within a few years of studying Original Blessing, a Shalom community friend and I were invited to teach creation spirituality as a continuing education min-course offered by Western University. I was absolutely delighted to co-teach the course – we taught it 2 or 3 times, if memory serves. For me, it was the perfect blend of teaching and quasi-preaching, the latter an aspiration burning since my Reverend Goth-would-be-orator days.

I am fully aware of the ironic connections among Salem United Church < > Siloam United Church < > Shalom community. The roots of my relationships in and around religion and spirituality are simply complex, one person’s = my w/restling with religion, circling around or better tilting at steeples figuratively. Writing about people like Goth, Hallman, Ryerson, Eckhart, Hildegard, and Fox and about events in my religious upbringing and about theological concepts and writings has been like drawing a thread of religious/spiritual filaments woven into the spiritual fabric of my life and my beliefs. It seems trite and important to say I truly am ‘thinking on paper’ – albeit, I am fully aware, in epic narrative form – in this blog, intending only to reflect and in no way to preach rightness or wrongness about any religion or belief system. I truly don’t judge people of any particular faith or religion. In fact, my ecclesiastical visits to different denominational churches such as those attended when I was a high school Key Club member remain cherished components of my memory. So too am I in awe of the rituals and practices of Jewish peoples – Shabbat; the lighting of the Yahrzeit candle on the anniversary of a father’s death; the significance of Yom Kippur traditions – most of these learned at the gracious, inclusive invitations of our deeply cherished friends.

At the same time, I shudder at the oxymoronic notion of “religious” or “holy” “wars” – there is absolutely nothing religious or holy about any war – and the horrific impact of depraved, cowardly acts like the Catholic Crusades of the 13th century or currently widespread, odious anti-Semitism. Even the subtleties of the Baptist theology in singing “Joy, Joy, Joy” where the word is acronymic for professed and ingrained priorities in life of Jesus-Others-You (‘You’ always last, ideally instilling selflessness in believers) strikes me as quasi-religious cloaks stultifying the development of healthy self-esteem Similarly, active evangelical Christianity where that religion’s ‘gospel’ and its colonial dispersion are held as the one true word is just so exclusionary of other significant religious and philosophical belief systems practiced by Hindus or Muslims or Buddhists. As I grew older and more constructively critical of United church doctrines, the less I could resolve the ‘Christian’ belief that one had to/has to believe in Christ to be ‘saved.’ How institutionally egocentric and exclusionary! The whole notion and concept of original blessing just seems more alluring, honouring, and respectful of humanity in all its glory. So I tumble home in this extensive blog to my ruminations and memories about my learning from organized religion, the oratorical grandiloquence of Reverend George Goth and my journeys and experiences connected to a lifetime of being a student and self-steward of/about religious/spiritual schooling, learning, and questing.