Masculinities absorbed

Today, as I turn 71 years of age, I choose to look in my life’s rearview mirror. In particular, I have been thinking about my boyhood in the black and white 1950s.Television shows were in black and white; photographs were black and white – perhaps dreams were too. The 50s were and remain for me enigmatic, mysterious, and compelling all at the same time. Immediately, I think of Edwin Brock’s marvellous poem, Five Ways to Kill a Man…

There are many cumbersome ways to kill a man.

You can make him carry a plank of wood

to the top of a hill and nail him to it.

To do this properly you require a crowd of people

wearing sandals, a cock that crows, a cloak

to dissect, a sponge, some vinegar and one

man to hammer the nails home.

Or you can take a length of steel,

shaped and chased in a traditional way,

and attempt to pierce the metal cage he wears.

But for this you need white horses,

English trees, men with bows and arrows,

at least two flags, a prince, and a

castle to hold your banquet in.

Dispensing with nobility, you may, if the wind

allows, blow gas at him. But then you need

a mile of mud sliced through with ditches,

not to mention black boots, bomb craters,

more mud, a plague of rats, a dozen songs

and some round hats made of steel.

In an age of aeroplanes, you may fly

miles above your victim and dispose of him by

pressing one small switch. All you then

require is an ocean to separate you, two

systems of government, a nation’s scientists,

several factories, a psychopath and

land that no-one needs for several years.

These are, as I began, cumbersome ways to kill a man.

Simpler, direct, and much more neat is to see

that he is living somewhere in the middle

of the twentieth century, and leave him there.

I love the subtleties of the examples of cumbersome ways to kill a man in the first four stanzas – crucifiction, lanced in a jousting contest, gassed in World War I, decimated by an atomic bomb. They are unsettling and suggestive and still prompt ‘hmmphs’ from me when I read them. However, the last 3 lines stung me when I first saw them in my early 40s and they stir me now as well. Born in 1949, I came alive literally in the middle of the 20th century and was left there. While it didn’t kill me – and I don’t think Brock meant ‘kill’ literally – I am a product of my mid-20th century environment. And, I don’t agree that being set down and left there is comparative to the horrific ways to kill a man listed by Brock. Nor do I feel being left here killed me; it most certainly shaped me. As a boy, I was heavily impacted by so many elements, people, concepts, images, and portrayals of what a man ‘should’ be, or, at least held up to youth in North America as a masculine ideal. In this blog, I want to wander back to the 1950s and look at some of the images, projections (literally and figuratively) and ideals I soaked up almost osmotically in mid-century – to ponder and reflect on those concepts now as I try to make sense of their impact on me as a young boy learning to be and do during the 1950s. Why this topic in COVID-19 times of 2020? Who knows…it is where my soul settled today.

What comes first to my mind’s eye is the Lone Ranger – “HiYo Silver Away,” I remember hearing Clayton Moore cry at the end of every episode of the Lone Ranger – the hero spurring and urging his horse, Silver to leave whatever feat of derring-do they completed and ride off into the proverbial sunset…

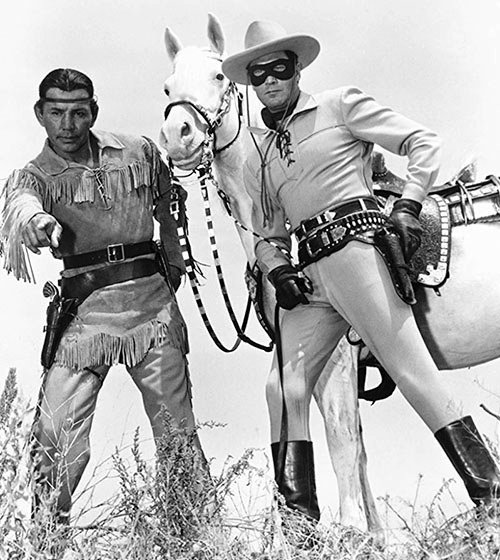

Masked, magnificent, sparkling, immaculate are the adjectives I envision now that inspired me then. Purveyor and dispenser of justice, the legend embedded was of a former Texas Ranger who, while riding with his fellow rangers, was ambushed by outlaws and left for dead. The Lone Ranger did not die but adopted the mask to protect his identity in the pursuit of the bad guys, the latter in abundance every week the television show aired. Canadian-born Jay Silverheels, a full-blooded Mohawk Native, was the Lone Ranger’s faithful companion, Tonto:

Muttering incomplete quasi-sentences, Tonto was rendered to stereotypes of the times and I/we thought nothing of it. Sometime in the 1980s or 1990s, a Toronto columnist wrote a scathing attack on what was reified about the lone ranger concept. I can’t find the article but the gist of it was how many boys were “lone rangered” out of our feelings. Tonto was, as I recall from the piece, monosyllabic and the Lone Ranger never stayed anywhere long enough to experience, let alone sustain a serious relationship, female or male. The columnist made great efforts to show how indelible this alone-ness was imprinted on young boys’ psyches during the 1950s. And very likely it was, my own psyche included. I watched justice meted out from guns; dramatic chases on horseback; heroic deeds saving whomever needed rescuing.

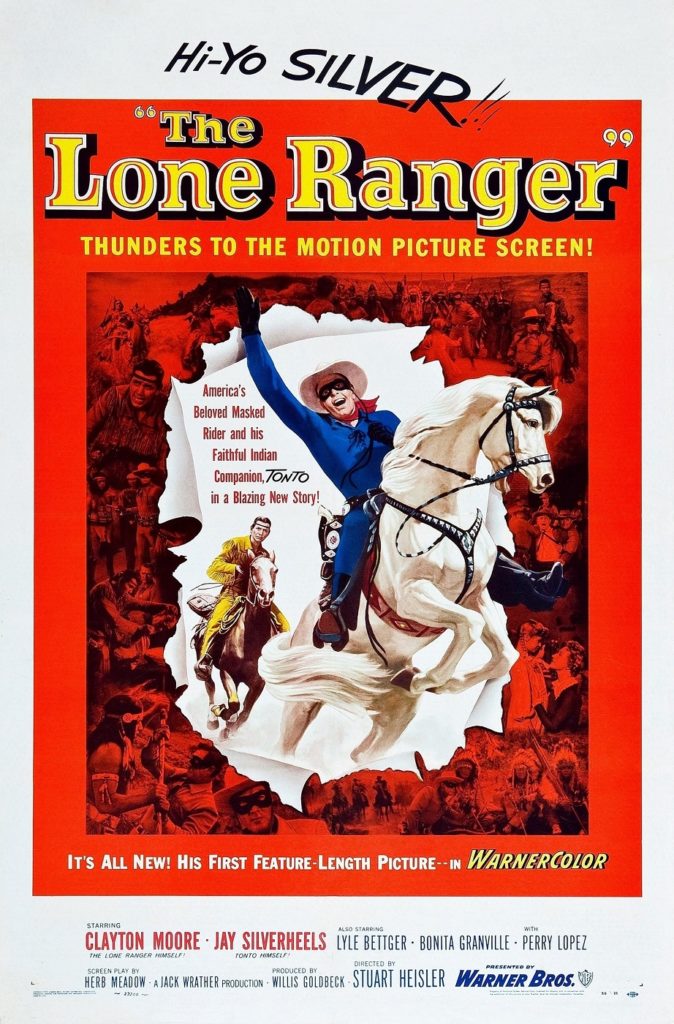

To be clear, the black-and-white of my Lone Ranger did morph into colours, some as radiant and alluring as this 1956 Lone Ranger movie poster:

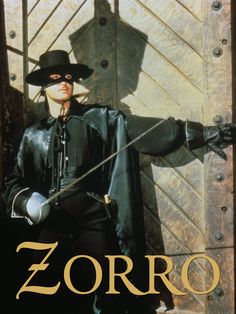

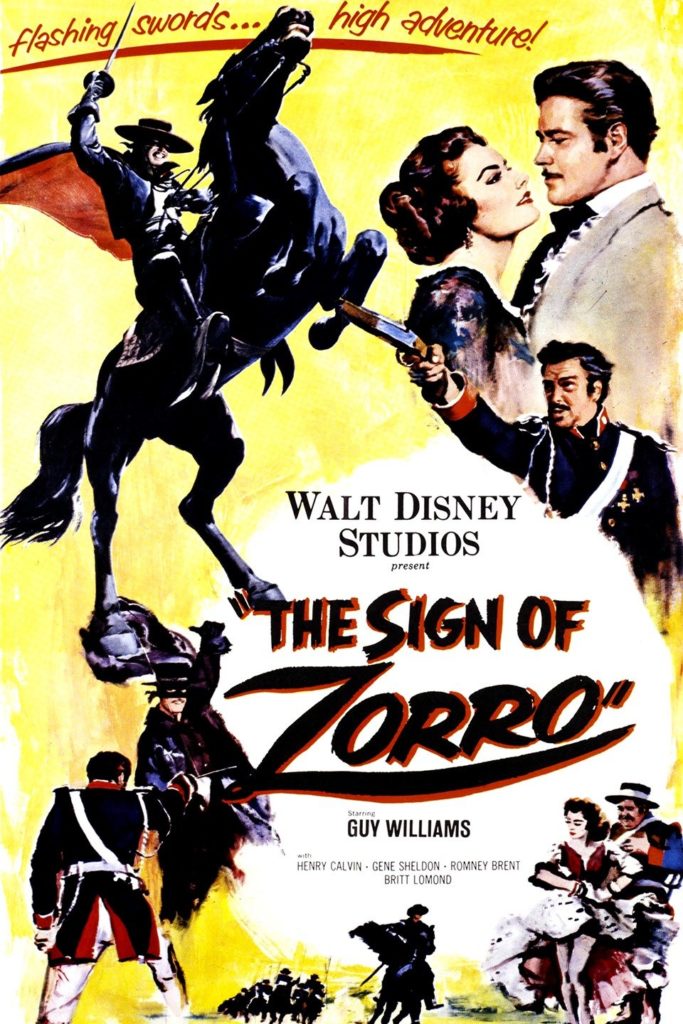

He was a man – clean, white like me, righteous, and so power-ful and heroic. And the mask captivated me just as it did with another of my boyhood televised and absorbed delights, Zorro:

Guy Williams was this masked, swashbuckling, sword-wielding crusader for justice. Zorro was the alter ego of nobleman Don Diego de la Vega. Zorro’s companion was Bernardo (Gene Sheldon), his mute servant, the vocal incompleteness so reflective of the Tonto character in the Lone Ranger even though Zorro seemed to interpret Bernardo’s sign language perfectly. The 1957-1959 series had a clown (don’t all good stories/dramas have clowns – Shakespeare taught us this), a buffoon, the bumbling, so clearly overweiht Seargent Garcia, always outwitted by Zorro, often with the latter’s sword-carved ‘Z’ etched into Garcia’s clothing. Caped, Zorro perpetually seemed to be jumping off buildings, vaulting roof structures, cape and sword always flared…

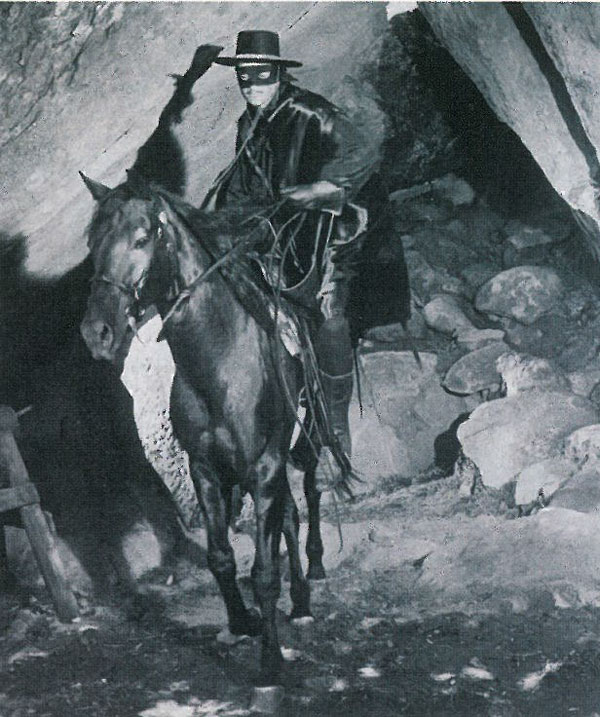

Guy Williams / Zorro was so handsome, so captivatingly cool under any kind of pressure. And it always seemed to be night when Zorro bolted from his cavernous lair beneath his mansion on his black stallion. Tornado (tor-NAH-do, not tor-Nay-do) was Zorros’ steed

The blackness of Zorro, his garb, his horse, and the night rides were counterpoint to the Lone Ranger’s whiteness…literally, for me, the black and white of the 50s. Every tv episode began and ended with the Zorro theme song and my heart raced every time I heard the Mellowmen sing it against the backdrop of Zorro riding, carving, smiling…so heroic, so emboldened and emboldening.

So, I became Zorro, masked, brimmed hat and all…

Me in my Zorro costume, modified mask, brimmed hat (circa 1958 in Trenton), nefariously nestled behind my sister Marnie and our housekeepter, the incomparable Nelly Geedie, my grandmother’s friend.

Me in my Zorro costume, modified mask, brimmed hat (circa 1958 in Trenton), nefariously nestled behind my sister Marnie and our housekeepter, the incomparable Nelly Geedie, my grandmother’s friend.

As I look back now, I remember the Don Diego aspect of Zorro being as alluring or perhaps magnetic in other ways. Guy Williams was incredibly handsome, played a guitar, and attended parties and even talked with women though he too never sustained a relationship either in the tv series or the two Zorro movies that came out in that era, the most prominent of which was the Disney production, The Sign of Zorro:

The suggestiveness of a love-life was certainly resplendent in the movie posters but my memory of the movie was of Zorro’s battles, his athleticism, his fights, and his triumphs over what was clearly evil in the world.

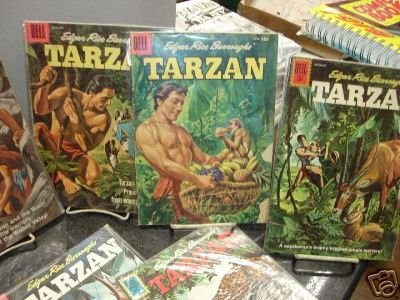

Tarzan of the jungle – not masked and certainly less clothed than the Lone Ranger or Zorro – fit my fifties mold of the male hero. I remember seeing the original Tarzan, Johnny Weissmuller, at movie theatres, I suspect. Embossed in my memory bank is an image of Olympian (1924 Games) swimmer Weismuller carving through often alligator-infested jungle rivers with his perfect, water-slicing crawl stroke, a human Evinrude-like motor:

In learning to swim during that era, I often thought of myself as Tarzan, emulating his stroke. Most assuredly, I longed to swing from vines – a tree-branch, knotted dangling rope with a tied-tire over the river in Exeter was the best I could do. And who among my boyhood friends and me did not try our best to mimic Weissmuller’s famous Tarzan-yell.

Apparently, so endemic of the Tarzan image was Weissmuller’s call-to-the-junlge-wild that it was dubbed in most Tarzan movies and tv shows in the 50s and for decades beyond. Highly stylized, as I see it now, one very skilled editor created a video called The Tarzan Song as a Golden Record of the 1950s. Embellished with all kinds of Tarzan representations from later decades, it does, in my view, portray the chest-thumping power of this “ape-man” and the legend he became. Significantly, Tarzan had a mate, Jane. Who can forget, from that time period, “me Tarzan, you Jane.” And Tarzan wandered his domain, hand-in-hand or co-swinging through the trees with Kala, the ape, presumably the one who raised Tarzan, according to the original novel – Tarzan of the Apes – by Edgar Rice Burroughs. As the Lone Ranger did with Tonto, as Zorro did with Bernardo, Tarzan communicated with Kala, endearingly. With Tarzan, I remember more than television- or movie-versions of Tarzan stories the Dell comics I devoured as readily as I could buy them:

Men then could live in the jungle, save lives, love animals, be powerful (with heart-stirring yell and all), and have a significant other.

In my mind then and now, there was no kinder or gentler 1950s cowboy than Roy Rogers and his beloved, Dale Evans:

Then and now, “happy trails to you,’ the Roy Rogers’ show theme song was just so idyllic:

Others are blue.

Here’s a happy one for you.

Until we meet again.

Happy trails to you,

Keep smiling until then.

Just sing a song, and bring the sunny weather.

Until we meet again.

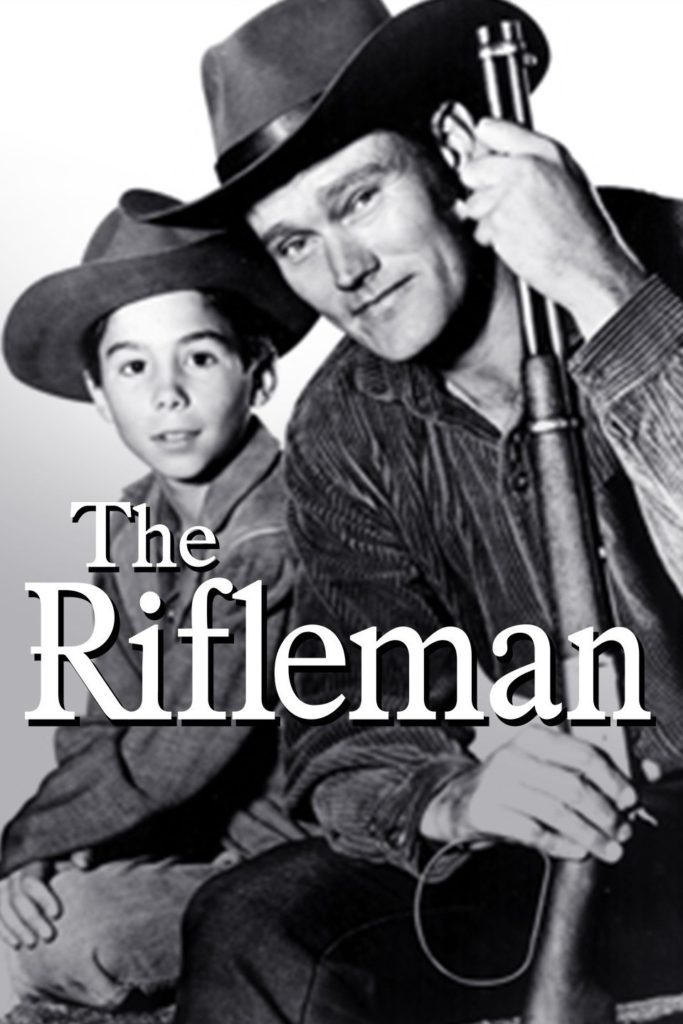

Starting in 1958 and running for 5 full seasons, Chuck Connors played the widowed rancher in The Rifleman. Though I am tempted now to compare Lucas McCain’s widowed status to that of my father, I’m not sure I made the connection at the time. Nevertheless, Lucas lived for his ‘boy’ and wielded his modified Winchester rifle with the big ring lever (in picture above) that allowed him to cock the gun by spinning the ring lever thereby shooting rapid-fire. For a short time, inclusive of its launch, the show was run by famed director, Sam Peckinpah. The square-jawed, homesteading Rifleman with kind of sardonic eyes was a no-nonsense defender of all that was good and right. More peacekeeper than lawman in the 1880s old West, it seemed like everything he did, everyone he shot was in the intersts of fair play, justice, and just being a good person:

I remember the show as compelling but then most westerns in the 50s and 60s were alluring to me. Heroes and men, I learned, could be fathers too, meting out justice from a rifle when needed.

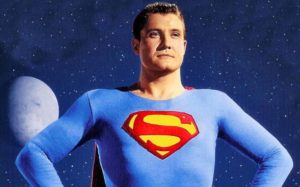

Throughout most of the 1950s, I thrilled to watch the above introduction to The Adventures of Superman, starring George Reeves.The words were riveting, at least to me:

“Faster than a speeding bullet! More powerful than a locomotive! Able to leap tall buildings at a single bound!”

“Look! Up in the sky!”

“It’s a bird!”

“It’s a plane!”

“It’s Superman!”

“Yes, it’s Superman – strange visitor from another planet who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. Superman – defender of law and order. champion of equal rights, valiant, courageous fighter against the forces of hate and prejudice, who disguised as Clark Kent, mild-mannered reporter for a great metropolitan newspaper, fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice and the American way.”

The conviction in the narrator’s voice, his sense of awe and wonder were magnetic. And Superman’s pose:

How could they not see behind his earthly disguise as Clark Kent, the “mild-mannered reporter…”

Even Lois Lane, enamoured with Superman could not see through his ‘mask,’ his Kent-disguise. Having super powers was the main appeal to me of this black and white tv show. What if I could bend steel with my bare hands or use my x-ray vision to the greater good or fly unassisted! Only kryptonite could render Superman to mere mortal status. Akin to Zorro and the Lone Ranger, Superman could not have a romantic relationship though Superman movies of later decades played with the love-life potential. I think I inhaled every Acton comic book featuring Superman.

For the life of me, I have no memory of buying comic books – the store, the place, how much (10 cents?) – I just know I had stacks of them, traded them. That aside, more than cowboys, Superman took me into my imagination, the place where anything was possible for this airborne, caped avenger, this man of steel. And though I hesitate to be tempocentristic or anachronistic re this 50s timeframe theme, the Crash Test Dummies’ Superman Song (1991), its cadence, deep tones, and words are so representative of what I remember about both Tarzan and Superman – every time I hear it now, my imagination returns me to my boyhood days.

Curiously, my 1950s heroes are armed – guns mostly. I don’t remember watching the late 50s show, Yancy Derringer but I recall vividly that I so yearned to own a derringer. On a trip to Kingston hospital to see my mother, just before she died, in a store window I saw a toy one, like this one…

I must have impressed on my father how much I wanted one because he gave it to me as a gift that Christmas. Its holster was plastic and could be affixed into a belt complete with the two bullets. The thrill to me was that it could be concealed in my hand. I am sure now that Brett Maverick had one in the tv series, Maverick:

I must have impressed on my father how much I wanted one because he gave it to me as a gift that Christmas. Its holster was plastic and could be affixed into a belt complete with the two bullets. The thrill to me was that it could be concealed in my hand. I am sure now that Brett Maverick had one in the tv series, Maverick:

And just so suave were Brett (James Garner) and Bart Maverick (Jack Kelly) and their exploits and gambling and heroic prowess. Somehow the decade produced, literally, a fascination with weapons, no less true for the knife wielding Jim Bowie in The Adventures of Jim Bowie tv series:

The television theme song lyricized the Bowie legend and prowess . . .

. . . Jim Bowie was not merely a skilled knife-throwere, he was bold, adventurous, powerful, indestructible, a fighter, and yet ‘tempered’ like the steel blade of his knife. I had a jack-knife and longed for a Bowie-blade, if not to be just like Jim Bowie.

Two other boyhood 1950s heroes entranced me and my imaginative projections onto ‘masculine’ heroes. One was that outlaw, Robin Hood and his band of Merry Men:

Robin was a skilled bowman, robbing from the rich to give to the poor. Friar Tuck, Will Scarlett, and “maid” Marion (my mother’s name) were his companions. Living and thriving in Sherwood Forest, perpetually outwitting the Sherriff of Nottingham’s soldiers – the whole premise was so geared to fanciful escapism and boyhood dreams to be just like Robin. How many bows did I make from tree sapplings and unsupple white twine. Men threw knives, shot arrows, saved poor people, and were always devilishly handsome.

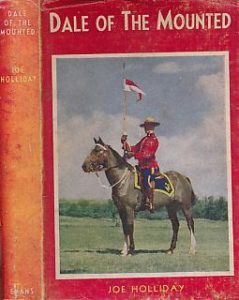

In contrast to Robin’s lawlessness, I read every Dale of the Mounted book – some 12 of them published, as I learn now, between 1951 and 1962 – I could acquire:

I don’t think there was a tv series but the books by Joe Holliday absolutely reinforced my heartfelt certainty that I was destined to become a member of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. There was such wholesomeness to Dale, even in his name. The constable-hero solved cases, was immersed in adventures across Canada and sometimes in places around the world I could only dream about visiting. At one time, I owned an RCMP hat, the stetson so emblematic of Dale and his fellow officers. Despite my father’s employment as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, no branch of the armed forces ever drew me as much as the fictional world of the RCMP enlivened by this series of books.

I arrive back where I started this blog, in reminiscent mood. As I read back on what I wrote, it seems astounding that I had time to do anything else other than absorb tv heroic series. And I didn’t even consider the children’s and cartoon shows I ingested and loved – Casper the Friendly Ghost: the Little Rascals with Spanky and Our Gang; Leave it to Beaver; My Three Sons (started in early 60s, I think); and my very favourite Looney Toons’ character, Foghorn Leghorn

And there were other western series full of impact on and excitement for me, some at the end of the 50s, some starting in the 60s – Hoppalong Cassidy (the earliest of tv westerns), I found William Boyd/Cassidy more of a wooden actor and his horse, Topper just did not ensnare me like Zorro and Tornado); Have Gun Will Travel, the Paladin western whose theme song stirred the tuning fork within my body; Daniel Boone; Gunsmoke (it always seemed more of an adult-appeal western to me); Hawkeye and Chingachgook in The Last of the Mohicans: Bonanza and its Ponderosa family of men (3 sons, one father, interesting concept); and later that impeccable movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Very likely there have been oodles of studies about popular culture in the 1950s and the shaping of boys in becoming men and the masculinities unveiled. Equally certain are the studies of archetypal patterns of white men, gunslingers, the hero as journey, and so forth. And I could look up that research and study their findings like a good academic, but I choose and deliberately chose not to do so. One of my colleagues used to offer, ‘avoid analysis paralysis’ – indeed, so easy and tempting is it to deconstruct and ferret out meanings. Part, a big part of writing this blog for me is just the sheer joy of re-membering and writing my stories and reminiscences.

What I learned in re-exploring my 1950s imprinted memories was the rapture of all those television, comic-book, and sometimes fictional representations of heroes. I loathe guns, always have and I detest violence and yet most of what, or better, who appealed to me brandished weapons, maimed, and killed…for justice but still…. There was an aloneness or an abbreviated, tacit companionship (Tonto, Bernardo, Dale, Jane…) to those men, an independence that I know is a big part of who I am. Long distance running still has huge appeal to me and I have long felt the aloneness – very different than loneliness – of the long distance runner. And there was a wonder-fulness to westerns too – escape, descent, and/or elevation into their lives, their exploits, their challenges that kept me spellbound, absorbed and dreaming, even mimicing their characters. Perhaps my professional historian interests in ‘doing/writing’ biographies (and reading life stories) stems from those men and all of their singular narratives. I remember fondly, from the early 1980s reading Lytton Strachey’s remarkable book, Eminent Victorians and his erudite study of 4 leading figures of that era. By no means is this blog-musing by any stretch equal or even proximal to Strachey’s work; however, it is part of my story of eminent, albeit fictional people who shaped my life from the time I was set down in the middle of the 20th century. Today, I tumble home to those memories and all my projections, to a decade long-ago when I felt so alive – a gift of feeling I cherish and nurture to this day.