courts … fives to pickleball

The allure of playing anything is timeless, universal. Play, in the game or activity sense (as compared to a theatrical play), is indefinable – there are no synonyms. We can play cards, monopoly, a piano, sports, lotteries, and so forth; however, one cannot point to something, as you would a fork or a tree, and say, “there, that’s play.” Play, as I see it, is an attitude. In an earlier blog – Jeu…what if… I discussed the more esoteric and perhaps academic-oriented meanings attached to play/games/sport. What I seek to do in this blog is to ruminate about my new-found fascination with a rapidly growing and very popular game/sport with the rather curious name of pickleball. In doing so, I also want to reflect on the meanings I have derived from playing all manner of court-based, racket sports and their antecedents and my experiential connections to pickleball.

For some years, I have longed to find a new sport to play, something that would cater to my need to move physically, challenge my athletic abilities, and mostly to feed my mind and/or my lifelong interest in being in the attitude of play. A sport junkie in many ways, I cannot remember ever being inactive. And yet, watching sport or observing others play has very little appeal to me. It is the experience of play that magnetizes me. More than any other forms of play, games, and/or sport, it is racket sports that have balmed my soul. Something there is that transforms me when I hold a badminton/squash/paddleball/racquetball/tennis, even table tennis – and now pickleball – racket. Courts, racket courts feel like home – their boundaries are clear, their lines are defining, and the creative possibilities once their games have begun are infinite. They place a premium on tracking, whether ball or shuttlecock, on hand-eye coordination, and most elegantly on touch – soft hands, quick wrist, shot preparation, service, stroke execution, and deception – all of these roll into decisions that become non-conscious – what some call unconscious competence – in the seconds or fractions of seconds that flash inwardly in the quality of making – and not-making – shots. As to the magnetic, seemingly indescribable allure of pickleball in particular, I read somewhere that someone said, “It’s a dopamine fountain.” And it’s true – an addiction that transfixes me.

Does it matter, this business or craft or profession of playing games? After all, “it’s just a game!” Is it? Better than anyone else, William Hazlitt (1778-1830), an English writer now considered one of the moste eminent critics and essayists in the history of the English language, eulogized about his friend John Cavanagh, the greatest fives – handball – player of Hazlitt’s era:

“It may be said that there are things of more importance than striking a ball against a wall — there are things indeed which make more noise and do as little good, such as making war and peace, making speeches, and answering them, making verses, and blotting them; making money and throwing it away. But the game of fives is what no one despises who has ever played at it. It is the finest exercise for the body, and the best relaxation for the mind. The Roman poet said that ‘Care mounted behind the horseman and stuck to his skirts.’ But this remark would not have applied to the fives-player. He who takes to playing at fives is twice young. He feels neither the past nor future ‘in the instant’. Debts, taxes, ‘domestic treason, foreign levy, nothing can touch him further.’ He has no other wish, no other thought, from the moment the game begins, but that of striking the ball, of placing it, of making it!”

~ The Death of John Cavanagh, by William Hazlitt, published in the Examiner in 1817

Indeed. When captivated within and by any game, nothing else does matter. Does playing at fives – presumably denoting five fingers of the hand – or any other racket/sport make a difference in the world? Are such games just a toy-world universe? When in the attitude of a game, when playing, there is an engagement, a thrall that is all-consuming, as Hazlitt so eloquently wrote in his homage to Cavanagh above.

A brief description or characterization of fives is important, if not merely for game- and game-evolution context. One of the oldest, if, arguably, the oldest fives’ court is that of famed Eton College (Berkshire, England), pictured below:

There is no back wall, sort of a 3-sided squash court with an odd structure on the left side-wall; both the game and the derivation of that unique structure are explained in this clip, What is Eton Fives? The game is still played and can be seen in a more modern iteration and court – doubles’ game in progress – illustrated below:

John Cavanagh, an Irish Catholic by birth, was a house painter, so adept at fives that he played for wagers, sometimes for dinners at various courts throughout England. Hazlitt, an avid player himself, described Cavanagh’s play in this fashion,

Whenever he touched the ball there was an end of the chase. His eye was certain, his hand fatal, his presence of mind complete. He could do what he pleased, and he always knew exactly what to do. He saw the whole game, and played it; took instant advantage of his adversary’s weakness, and recovered balls, as if by a miracle and from sudden thought, that every one gave for lost. He had equal power and skill, quickness, and judgment. He could either outwit his antagonist by finesse, or beat him by main strength….[he] never volleyed, but let the balls hop; but if they rose an inch from the ground he never missed having them. There was not only nobody equal, but nobody second to him. It is supposed that he could give any other player half the game, or beat him with his left hand. ~ extracted from Hazlitt’s essay, The Indian Juggler (full text here).

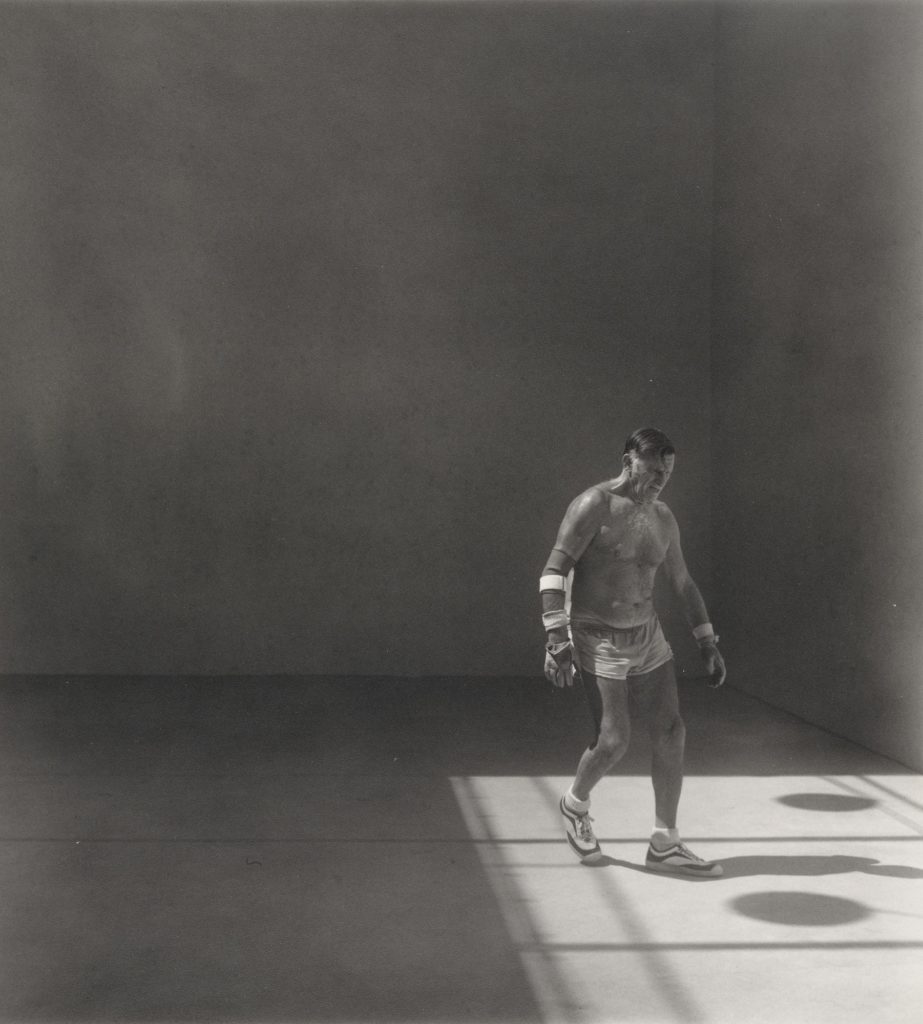

My point is not to proclaim or laud either Cavanagh or Hazlitt. Instead, I seek to find words to express the meaning of being enraptured, totally enveloped by a game, in Cavanagh’s case, to be so good at it, so aligned with his game that no one could beat him at his craft. Modern, 20th century handball, played in 4-walled, often wooden courts became popular in singles’ and doubles’ versions at private sport clubs, universities, and other venues. Like its fives’ ancestor, handball requires one to be adept with both hands, each of which can be gloved. As an Undergraduate, I tried handball on wooden courts in the PE building, Thames Hall, at Western University. My hands were always swollen from the ball impact on un-gloved palms for a few days after playing handball; regardless, this non-racket, court game held very little appeal to me. The game can be and still is played on one-wall courts, outdoor 3-wall courts and its devotees proclaim, ‘all you need is a ball and a wall.’ I remember handball as a 4-wall court game, somehow its courts buried in the bowels of athletic facilities; it was a taxing, sweaty game, played by men – and by women too – who looked like gladiators in their attire and hand/arm-ware – the image of Jerome Leibling below is representative of my mind’s eye recollections about the sport:

Handball is still called fives with one of the most prominent venues located at the sports-venerated Rugby Public (= private school, in North America) School. Below is an image of a recent British Nationals’ Fives championship hosted at the Rugby courts:

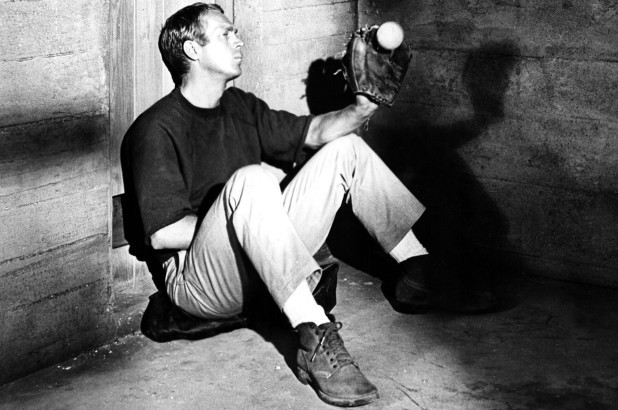

And, although he used a baseball and glove, the movie scenes of Steve McQueen, in The Great Escape (1963), repeatedly incarcerated for his failed prison escape attempts, seated in ‘the cooler’ playing catch with himself , throwing the ball against the cell-wall portrays so demonstrably, the riveting call of ball-to-wall play/games:

For me and many, many others, there is something about a court game with or without walls that enchants its devotees and players. Pictured below is a real or royal tennis court:

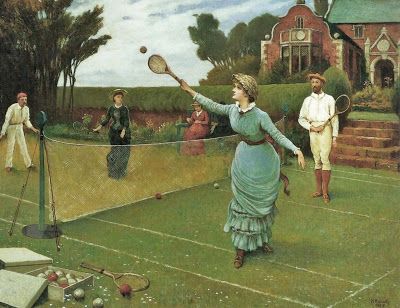

The modern game of tennis is derived from this indoor court game played by the elite on English and French courts. Reputedly, the oldest real tennis court was commissioned and built by King James IV sometime early in the 1500s; King Henry VIII played real tennis – he “held court” then in more ways than one. Royal tennis is complex in its rules and scoring with use of the walls, the roof of the small gallery, and even the windows deemed in-play. The racquet was/is more pear-shaped and lopsided, likely to impart spin on the balls, themselves typically manufactured from cloth, by hand.. Note the height of the net; serving has to be done underhand. Wall-free tennis, lawn tennis was not ‘invented’ until the mid- to late-nineteenth century:

The outdoor court game could be played on almost any surface and women, at least those from the upper class in Victorian society, did play the game. In some caricatures and daguerrotype (camera forerunner) renderings of early lawn tennis, there is evidence that serving was underhand, as it was in the royal/real court game and that serving may have been done from a diamond shaped area marked out in the middle of the court, not at the baseline. In the latter regard, some images show the service-return areas to be in the back two-thirds of the courts rather than extending from the net for the front two-thirds of the court as is the case today. It is interesting that in the early forms of both real and lawn tennis, the net is low and volleying – hitting the ball before it bounced – seemed to be the norm in shot-making. Personally, I have never played lawn tennis; instead, I took to its hard-court version in high school, playing on tarmac courts during spare periods and mostly for long hours on hot Summer days, quaffing 26-ounce bottles of Coca Cola after matches with my friends.

Two other court racket sports evolved either from the indoor tennis game or perhaps from the example set in fives’ courts – racquetball and squash.

Above is a very modern, glass backwall image of a racquetball court. Of all the indoor court games, my personal experience is that racquetball is the most demanding physically, with hand-ball a close second. While the court width is about the same as a squash court, a racquetball court is almost 10 feet longer and the ceiling is very much in play. Most shots are up and down the side walls, either driven hard along those walls or lofted high in the air. Players spend most parts of rallies hitting the ball “safely” such that they hit it off the ceiling so that it then bounces off the front wall and then ricochets off the floor bouncing high along either side wall; a well-hit ceiling shot is usually retrieved near the backwall, high above a player’s head. Thus, the power-demands of hitting the rubber-ball with a kind of sawed-off tennis racket are considerable and the longer court means players build up a lot of momentum in repeated accelerations, pivots, and stops.

Squash. For more than 50 years, since mid-high school, I have played the game of squash from an intercollegiate competitive level to (mostly) recreational. For the first 15 years, I played hardball or American squash; the ball was harder (did not compress), the courts were narrower, and the sideline boundaries higher than the international game played almost exclusively now. I spent hours and hours of time on the court with my mentor – of squash and academic interests – Jack Fairs, he who was and is so skilled at teaching the game. I learned more about court positioning, strategies, shot selection, stroke deception (making your opponent ‘see’ something different in shot preparation and execution that what you would end up doing with a shot), angles, drop shots, service (hard and lob), controlling the ‘T’ or central part of the court, boast (2- or 3-wall) shots, how to cup the ball to impart under- or back-spin, and reverse corners. If not on the court, I could read Jack’s articles on squash; one title in particular stood out then as it does now, “A Portrait of the Phlegmatic Server” wherein Jack made a case for using the service as an offensive weapon, to force your opponent to make a safe or defensive shot or even to make an error, not merely to put the ball in play.

Jack directed me to legendary world champion Hashim Khan – of Cavanagh ilk in his domination of squash during the 1950s and 1960s – and his book, Squash Racquets: The Khan Game, a text dictated to a professional writer who left its syntax in the broken English Hashim used in rendering his knowledge of the game. As stoccato as the writing was, there was so much to be learned from Khan’s experience. I bought and cherished a small arsenal of coveted Bancroft wooden rackets, gut-strung, and relished my time learning, playing, competing in, and, by the late seventies, teaching squash to Physical Education students. As a slight aside, of all the students I coached or taught in any sport, by far the individual who picked up squash skills the fastest is my wife, Jen, and I say that without reservation or exaggeration or bias – she just oozed racket skill acquisition talent in what to her was a brand new sport. See the image below of Jen learning to hit a forehand squash shot – her racket preparation, getting her body low to the ground, especially her left leg, reaching her non-racket hand toward the ball, all of those are elements not normally acquired until a few years after playing squash; Jen learned these skills within a few months, seemingly by athletic osmosis:

At one point, during the seeming throes of completing my dissertation, I was hired by the London Squash Club to become its club-professional, a post I turned down in deference to completing my degree and becoming a university professor. During the early 1980s, I joined the that squash club as a paying member and turned my attention to schooling myself in the international version of squash. The modern, international court is imaged below:

Played with a much softer ball, one that actually could be compressed or squashed between two fingers, this more widely-played game placed a premium on longer rallies, slightly different stroke mechanics, and demanded more aerobic fitness than what I had experienced in hardball squash. Throughout the last 3, almost 4 decades, this game and I have been co-dependent. My introduction to the softball game was at The University of Alberta in 1975 when I defended my doctoral dissertation; a young phd-student, Craig Hall, just beginning his graduate work, offered to play squash with me when I came to Edmonton on leave from my full time professorial job at Western to complete my graduate work. I recall being quite thrashed in performance and outcome of those games. However, Craig eventually became a colleague at Western and he and I played squash once a week for more than 40 years; he remained interested in tournament competition and became far more adept at the game than I ever did. And I cherish the times he and I spent at-play on the London club courts.

While keeping score and winning in sports is, by definition, the apparent outcome of all games, I was never possessed of enough ‘killer-instinct’ to become dominant in this game or in any court- or sport-game I played. In fact, I spent hours hitting a tennis ball against the outdoor, bricked west wall of my high school gymnasium, more interested in what I could do with my racket rather than how well I could do in game outcomes. My quest and belief in every game I played in any form was to play the best I could; if my opponents did the same, then we co-created a game magnificence that tanscended, at least for me, merely winning games and matches. To play well in anything I do is my deepest desire. Renowned American football coach, Vince Lombardi is reputed to have said, “winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” Implications abounded in such declared, chest-thumping adages as winning beats anything that comes in second; being second in a sport is being the first loser; to end a game in a draw or tie in sport has the same satisfaction as kissing your sibling, etc. What I discovered Lombardi actually said is this: “winning isn’t everything, the process of winning is.” There is a huge difference in the two maxims. I believe/d in the process of playing, otherwise why not just play the final minute of any contest!? I am reminded of Rudyard Kipling’s lines from his well known poem, “If” – If you can meet with triumph and disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same. Although often used as inspirational words at sporting venues, for me, winning a game is not a triumph, losing not a disaster even though fans and players of elite sport often behave as though that were the case. I love the word ‘impostors’ from the Kipling verse – they are impostors because they represent people’s aggrandized perceptions of them, especially in games/sports. Winning is ephemeral; playing and being at-play is exquisite and so much more satisfying than the final score.

For me, there is a euphoria in playing court games. As Ken Dryden so elegantly expressed it in The Game, his 1983 classic treatise on the meaning of ice-hockey to him, “the game breathes.” One of my most treasured, published academic articles that I penned was “Timelessness and Historicity of the game in Ken Dryden’s The Game” (in Sport History Review, 2006; see this link for an updated, 2019 version of that article). A lot of what I believe about games comes from Dryden’s magnificent book. Games have a life of their own, archetypically – as mother is an archetype, a universal encapsulation of a concept beyond one specific mother. Dryden opined that we bond with a game; games have tempos and moods; we wait for a/the game; there is an endless panorama of games. He proclaimed:

…what I enjoy most…now is the game itself; feeling myself slowly immerse in it, finding its rhythm, anticipating it, getting there before it does…(page 136 of The Game).

I concur wholeheartedly; games are felt in the moment. The courts, in my case, may be exactly the same in dimension, rules of play, and so forth. And yet every game of badminton, tennis, squash is different in the moment we play it/them.There is never a tedium, same-old, same-old, at least not to me; I held the same view about teaching – I felt I did not teach a subject/area, rather, I taught students – there is a chasm of difference. Dryden was and is unique in his ability to see his game, hockey, introspectively, to watch it kaleidoscope in front of him:

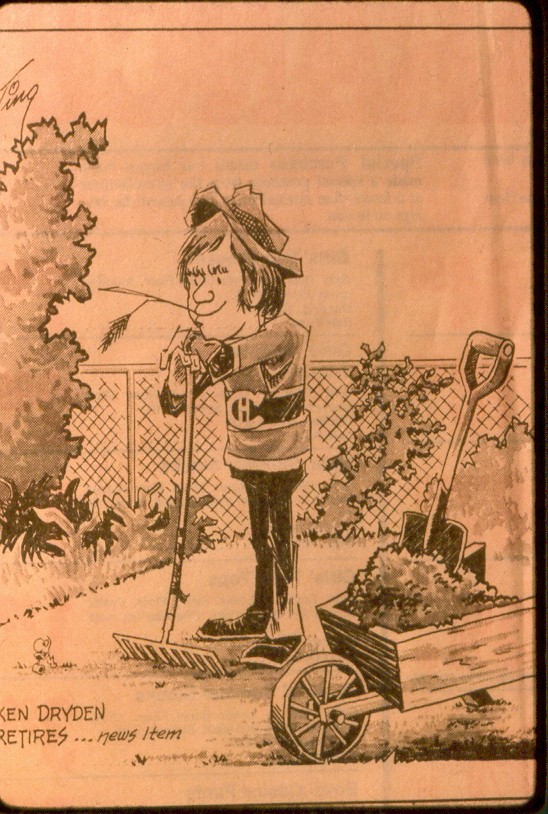

And when Ken Dryden retired, his image was so cleverly captured – transmuted from his omniscient goaltender pose, leaning on his stick watching his game unfold on the ice-scape in front of him to the same stance but leaning on a garden rake, by cartoonist, Merle Tingley/Ting:

~ The London Free Press, 11 July 1979, reprinted by permission with purchase

In late August or early September of this year, I made a very difficult decision to leave squash, to give up my decades-long membership at the London Squash Club, to retire from its game. While badminton was probably my ‘best’ sport in terms of skill – certainly it was my earliest learning about court games – and while I revelled in the feel of feather birds/shuttlecocks on my Yonex rackets and the penetrating cold of the luxurious green-backgrounded courts and draped lights of the Woodstock Badminton Club, it was squash that kept me in the court of racket games. At 70 years of age, I still felt and feel that I can play squash reasonably well, enjoy its game-ness…and I was done and it was not an easy decision. What has replaced my love of court games is pickleball. And it seems even the Woodstock Badminton Club (where I played often during high school), illustrated below, has merged badminton with the escalating demand for and interest in the newer game:

There are different narratives about who and when pickleball was invented and named. It seems it came about on the US west coast in the mid-1960s. Regardless of its name, it draws on elements of badminton (the court dimensions are almost identical to those of badminton), tennis (the net looks about the same as a tennis net, just slightly lower), and its forerunner paddleball. The best description of the game is that it is like playing table tennis on a court the size of a badminton court; the strokes in the two games are very similar. In high school, our PE teachers introduced us to one-wall – two walls if we played on either end of the painted, concrete-block walled gymnasium – paddleball with wooden rackets and a rubber ball that resembled the core of a tennis ball. And in university, we were able to use the 3, wood-walled (4-walled) courts in Thames Hall for recreational paddleball. The game was so popular at Western that there were tournaments played at the intramural level complete with as many spectators as could crowd in the restricted ‘gallery’ space above the courts. At the time, there were locker room attendants who handed out towels, gym-strip, and sports’ equipment from the ‘cage’ or large storage room at the locker room entrances. One of the attendants, Andy Biemans, started his own business making and selling the wooden rackets – for $5.00 each, if memory serves – I still have mine; it hangs demurely, in a place of honour, just underneath some 12-guage electricial wire, in my tool room…

White-adhesive taped on the edges and grip, the rackets had a wrist-strap likely to ensure the racket did not slip from our grip and hit another player unintentionally. Played in the equivalent size to a squash court, paddeleball games could be played as a singles,’ doubles,’ and a very unique cut-throat form; in the latter, it was 2 against 1 with the server continuing to serve as long as that person won the rally. The cut-throat game placed quite a premium on fitness because of the need to cover the full court against two players. Cut-throat may be possible in handball but not in squash because of racket length and the danger of hitting other players, although 3-player drills were/are common in squash. Net-based racket sports could have 2 players on one side using the doubles’ boundaries and the one player on the other side using singles’ lines. In paddleball, I preferred singles with cut-throat a close second and loved the doubles for the challenge of strategy and moving with 3 other people in the court space. The ball was like a racquetball ball except that it had a small hole punctured in it; otherwise, the ball would have moved too fast in the small court.

It seems tautological that pickleball morphed from paddleball, badminton, and tennis elements. The current pickleball racket and ball are pictured below:

Opinions differ on the reason for the game’s name – by consensus, it seems to be named after one of the founder’s dogs, Pickles who loved to chase the playing-balls when the game was in its infancy – hence, pickleball. There is a video, somewhat lengthy, that describes the game’s origins. The core or interior of the current paddle is usually made of some polymer with tensile, honeycomb-structured strength and the exterior or facing material is of graphite or fiberglass or most commonly now, carbon fiber. Pickleball balls are synthesized from plastics, are about 3 inches in diameter, perforated with holes, and weigh an ounce. The game is played indoors and outdoors (often on converted tennis courts); when played outdoors, the ball utilized is slightly heavier with more holes to adjust for wind factors that are not an issue with the indoor game. In the picture of the pickleball courts below, I am struck by how similar the court structure and net height is to early lawn tennis described earlier in this blog:

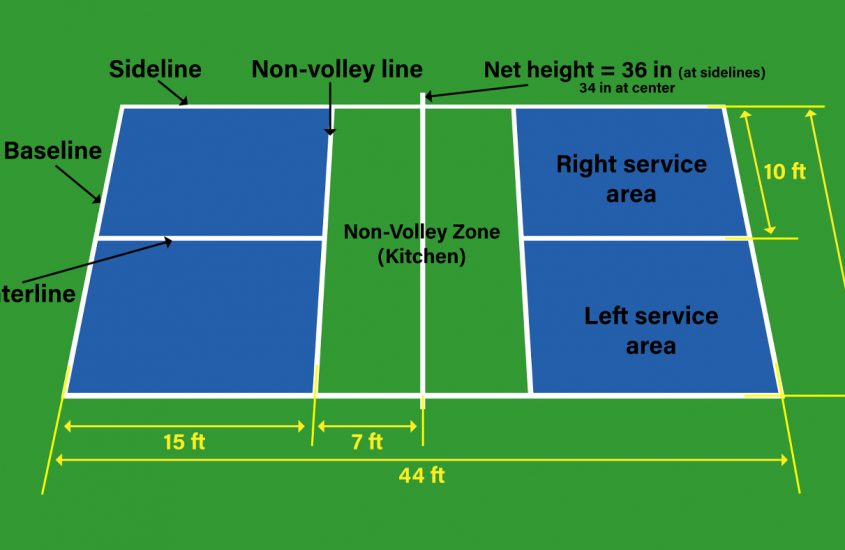

What makes the game intriguing to me and its devotees is the brilliant idea to incorporate a “kitchen” or ‘no-volley area 7 feet from the net on either side:

Of interest, if pickleball is played on a badminton court with only badminton lines, the 7-foot line is really 6 feet, 5 inches and that half a foot difference is noticeable to experienced players. The term kitchen is likely derived from the terminology of the game of shuffleboard; in the latter game, it is the area behind the primary scoring zones – if you land in and/or your disc is pushed into that kitchen, 10 points are deducted. In pickleball, you cannot stand in the kitchen when striking the ball unless the ball has already bounced in that non-volley zone. The whole game strategy and shot-making revolves around player positioning relative to the non-volley line (that line is considered part of the kitchen so you cannot have any part of your foot on the non-volley line when hitting the ball). Because of court-demand, most recreational and tournaments games are doubles – two people on each team – and I’ve utilized doubles in describing the game and my experience with and allure to that form of the game.

Briefly, service is underhand, performed behind the baseline to the diagonally opposite court, attempting, for the most part, to have the ball land near the opponent’s baseline. No part of the hand can be higher than the wrist when contacting the ball during service and the service motion at ball-contact must be below the waist or navel. Service return is usually focused on deep returns – to the baseline – as well. Each game goes to 11, you can only score on your own service, and you have to win by at least 2 points; for example, an 11-10 score requires the game to continue at least one more point to 12-10, or longer if the score is tied 11-11. In general, the overall strategy of each rally is for one team to gain court advantage by getting both players to the non-volley line while trying to keep the opposing team’s players at the back of the court. For most games, unless an error occurs in serving (server misses the return court, hits the net) or returning service (return player hits the ball out of the boundary lines or into the net), the heart of the game centres around – some say the game actually starts with – the “third shot.”

Players can hit the ball flat, with underspin, or topspin in efforts to force the opposing players to make an error. Because the paddle is relatively smooth compared to a tennis racket, creating spin off of the racket takes practice and is not as pronounced as in strung racket sports. Players cannot hit the ball in the air, that is volley it, until after the third shot has been hit. Thus, the tactic of hitting the third shot, assuming a good, deep service return is to hit the ball low enough and with very little pace such that the opposing team is forced to let the ball bounce in the kitchen and then, with a low bounce, hit the ball up to other team or dink the ball just over the net to bounce in the serving team’s kitchen. In higher player skill level play, about two-thirds of the game’s shots are ones of ‘dink’ or soft, well controlled shots, low to the net, landing in the kitchen with both sets of players standing just behind the non-volley line. More recently, the pro and recreational games are trending toward hitting harder, offensive shots – getting into very fast, hard rallies called fire-fights – rather than the dinking premium. Players can lob the ball, hopefully toward the back of the court, as both an offensive lob or as a defensive lob when caught out of position. If you watch even a few or the rallies in this men’s world doubles’ championship pickleball match, it provides a more vivid profile of the game’s dink-shot nature, court-positions etc.

For me, the game has been refreshing, skill-demanding, challenging, and fun experiences I have ever had in a racket-sport game. It is not as aerobically taxing as doubles’ tennis or badminton; however, it requires a lot of concentration, so much so, that it seems as mentally-exacting as it is physical-skills’ rigorous. To paraphrase baseball great, Yogi Berra ‘the game is 90% mental, the other half is physical.’ A player needs to have court awareness regarding the opposing team’s location, their shot selection, your partner’s position, the best next shot selection, moving in concert with your partner – it’s a dance, really, where players side-shuffle in tandem – watching the ball at all times, not making unforced errors, being patient in waiting for offensive opportunities, and so forth. In learning the game, there has been a lot of skill transfer from squash, paddleball, and tennis in hitting ground strokes, forehand and backhand after the ball has bounced. In those strokes, the ball can be hit very hard but unless well-placed or if your opponents are out of position of if your opponent has hit too short a lob (you can do overhead smashes with balls that are hit high, as long as you are not in the kitchen), shots with a lot of pace are not as effective as well-placed shots and/or shots that force the opposing players to hit the ball up from a low bounce. Whereas squash shots come from a lot of torque and wrist-control, more and more I find that pickleball places a premium on bending my knees and using more full-arm and body upward and outward momentum with different grip strengths and a firmer wrist especially for dink shots and third shots – more like table tennis shots.

So I arrive back where I started this blog, exploring court sports, the feel of hand- and racket-games. In pickleball, I have learned more about how to split step at the moment of an opponent’s ball contact; to stay out of no-person’s land, that is, getting stuck half-way between the no-volley line and the baseline, too vulnerable to too many of the other team’s shot repertoire; to do the kind of side-step dance at the 7-foot line, in concert with my partner and the other team members’ lateral movement; to use more topspin that my ingrained underspin from tennis and squash; to punch-volley to a target area – often toward my opponents’ feet – when returning a shot coming at me with pace or speed; to side-step or shuffle to retrieve dink shots, not do cross-over steps; to both protect the middle from offensive shots and to use the middle of the court when making shots – ‘up the middle solves the riddle,’ as one of my game friends reminds me; to think at least one or two shots ahead once the third shot has been established; to both feel and hear the ball when it comes off the sweet or ideal spot on my racket; never to take my eye off the ball even trying to ‘see’ the ball coming off my racket; to vary my shots – the odd lob serve, for example – to decrease opponents’ anticipation; to stop wherever I am when an opponent is making ball contact; to move my feet always to get into position to hit every shot, even pivoting to step back from a deep shot in order to get ready to hit it effectively; to make my third shots carefully transititioning 3rd to 5th to 7th shots; to learn watching others play; and mostly to be so enchanted with being at-play in the game that I could just roll over and butter myself regardless of the score. There are levels of play in pickleball, from 0 or beginner to level 5, indicative of game mastery. I suspect I will strive toward five-ness (how could I not) residing as I am now comfortably at about a 3 or 3.25, but only because it’s the striving that bewitches me.

Meaning, I know, resides in people not words or activities or doing or being – it depends where you find meaning in life – in playing a musical instrument, in doing mathematics, in designing or building houses, it matters not – and where we choose to put our energies, our awareness, and our attitude/s toward a game, life’s game, any game. I am aware of the enticement, even seduction of any game-court to me. Something there is about a net dividing a court – see this video clip about portable table tennis nets – and perhaps there are deeper meanings to play than just play. I think, for example, of Hermann Hess’s futuristic novel, The Glass Bead Game (Magister Ludi – Master of the Game) and his poignant metaphor that could be about both his bead game or an apt description of 4 players moving on a pickleball court:

I read, and saw those hieroglyphic forms

Couple and part, and coalesce in swarms,

Dance for a while together, separate,

Once more in newer patterns integrate,

A kaleidoscope of endless metaphors-

And each some vaster, fresher sense explores…

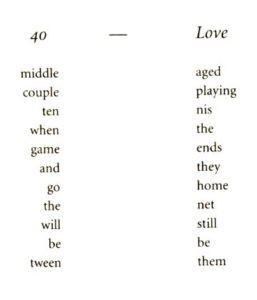

And there is Roger McCough’s wonderful “tennis” poem, 40 – Love that takes us under the court-surface of the game:

Something there is about a court, a net, a ball or projectile of some sort, a racket, and most of all, a willing suspension to unnecessary obstacles, that just is so magnetic and all-consuming. I have loved playing any racket game – even learning poona, the Indian version of badminton using a knitted, light ball – and one day I’ll see what some say is the fastest racket game in the world, pelota or jai alai, the Basque racket game, now so popular as a spectator sport with rampant gambling in Florida – video here – played with a cesta racket on an elongated, 3-wall court:

Something there is about a court, a net, a ball or projectile of some sort, a racket, and most of all, a willing suspension to unnecessary obstacles, that just is so magnetic and all-consuming. I have loved playing any racket game – even learning poona, the Indian version of badminton using a knitted, light ball – and one day I’ll see what some say is the fastest racket game in the world, pelota or jai alai, the Basque racket game, now so popular as a spectator sport with rampant gambling in Florida – video here – played with a cesta racket on an elongated, 3-wall court:

A jai alai or pelota court, doubles game in progress. The one, open or non-wall side of the court reveals the game’s spectatorial appeal. This game too has remnants of early royal, real, or court tennis.

The newest, at least to me, of court-racket sports is padel (pronounced pa-dell, accent on the first ‘pa’ syllable) tennis. A variant of an enclosed form of tennis called platform tennis (never popularized), the game was invented in Acapulco sometime around 1969. it seemed to root itself in Spain such that by the early 2000s, there were 500 padel clubs in that country. By one 2019 estimate, there are now more than 11,000 padel courts in Spain, 8000 in Argentina, and more than 500 in each of Brazil, Italy, and France. Public courts are now available in 57 countries worldwide. The first world championship took place in Madrid in 1992. Since then, padel has grown very rapidly to become a very popular court-sport in Europe, South America, Scandinavia, the UK, Latin America, eastern countries like China where there is huge investment in the new sport from the powerful Chinese Tennis Association, and the United States. The game is played in an enclosed, 4-walled, kind of scaled down tennis court like this one:

The 10 by 20-metre court, its markings, and net remind me of early lawn tennis and in style of play, padel combines, tennis, squash, and pickleball – the walls are in-play just as they are in squash. There is a cute cartoon video here that explains the game visually. Hailed by one writer as “the biggest sport you’ve never heard of,” some feel padel is the fastest growing sport globally. The ball differs little from a tennis ball, just slightly less air pressure inside the padel ball and the racket looks like this:

Scoring is exactly the same as regular tennis and the serve is underhand, the same as in pickleball. Padel is growing exponentially with outdoor courts being the norm. Intriguingly, one personally-owned yacht, the 98-metre, Aviva has a full-sized indoor padel court in and on which crew, passengers, and owner are encouraged to play. In our country there is now the Canadian Padel Tennis Association, a private organization founded on Tobin Island in the Ontario Muskoka region. The association is the leading authority for padel tennis in Canada. The CPTA is the home of the first indoor padel tennis court in Canada. It would seem that just like pickleball, padel as a game or sport is easy to learn, tough to master.

For now, I I tumble home to and revel in pickleball, the people I play with, and the elusive wizardry of the game. It is a passion of my play…a game I play with my passion as I tumble to a new court-home…with one eye open to padel’s growth and development in Canada, but my feet ‘dancing’ on pickleball courts.