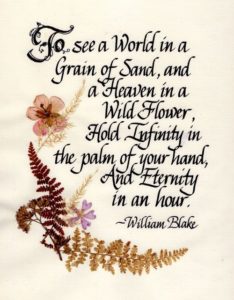

Expressions, quotations, pithy and/or humorous sayings, metaphors…lines from novels, songs, and poetry all inspire me and, often, ignite my imagination, admiration and very often leave me in awe. There are only 26 letters in the English alphabet; it stuns me that new words and phrases come into our lexicon seemingly without end. In this blog, I want to remind myself, and others, of the power and beauty of words – a kind of aesthetic etymological recollection. Very likely, this will be an ongoing blog, that is, open-ended as I remember more ways of perceiving meanings from cogent phrases and add them to this blog over time. As I compose this introduction, I am reminded of what the word ‘inspiring’ means – to be breathing, as one would inspire air. By extension, to con-spire with someone might be viewed as breathing with them; however, conspire is usually taken to be some sense of making plans to create harm or some negative result. In my way of thinking, words elegantly arranged help us breathe together, to understand, to create meanings and inspirations – to see a world in a grain of sand, as poet William Blake famously put it in the poem, Auguries of Innocence.

Years ago, English and Blake scholar Dr Ross Woodman related to me that Blake wrote with a quill-pen and that often, making the shape of a letter predetermined what he composed. True or not, that story adds greater richness to Blake’s expressive genius – his body-hand co-created his poetry. As William Butler Yeats asked,

“How can we know the dancer from the dance?” (Among School Children).

Yeats’ elegant question gives us pause to consider how much some creative acts are so connected to the artist/poet/person that it is almost impossible to separate the creation from the creator. Perhaps the religious and/or spiritual connotations are the ultimate implication of Yeats’ acclaimed query.

Immediately as I note Blake’s elegance, I am transported to his contemporary, William Wordsworth (could any last name be more apt) and his lyrical poem’s I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud opening verse:

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

~

The impact on me is immediate and potent – the expression ‘all at once’ rarely conjures suddenly coming upon a field of daffodils, let alone a crowd or host, both almost personifications of the flowers. What touch of genius to pair ‘crowd’ and ‘host’ not merely with daffodils, but framed with such a gilded adjective as ‘golden’ [daffodils]! And, the poet’s use of ‘I’ reminds me – completely aside from Wordsworth’s intent – of a line from a blog post in

Brain Pickings “.

..the small i, the I lowered from the pedastal of ego.“

Conveying meaning is such an art-form and poets do it so incredibly well. Sometimes it is just so subtle as when a colleague from Eastern Tennessee State University, Don Johnson penned a tribute to his friend’s father in a poem called Grabbling. In the verse, a young man is trying to fathom how a veteran fisherman can catch fish with his bare hands (called grabbling or guddling, a current sport in the southern US) underwater all the while holding his breath for minutes at a time. The opening lines of the poem describe, with awe the ability of the fisherman to remain underwater; a single, 3-letter word grabbed me the first time I read it and has astounded me ever since:

Longer than any of us in air

Or common light could not breathe

He would stay down, fishing

By braille in pools darker

Than the skins of old bibles.

There is a richness to the imagery in ‘fishing by braille‘ and ‘darker than the skins of old bibles,‘ both conveying a sense of reverence for the activity. However, it is the word ‘not‘ in the second line that still astounds me. Not-breathing is the perfect and yet highly unusual use of words to describe holding one’s breath. A less seasoned poet might have used a different set of words but Johnson makes us/me take note of the ‘not breathe.’ I a-spire to be so deft in my word descriptors!

Sometimes it’s a single (often contextually qualified) word – ‘strengths’ is the longest word in the English language with only one vowel – and just as often one line that reverberates with meaning for me, like the Yeats’ dancer/dance question noted above. I used to teach poetry, ostensibly about sport but much more about using sport terminology or images or words to show how and why sport has more meaning than the mere playing of games for winning. In a poem called Pitcher, Robert Francis takes us inside the nuances of pitching a baseball and uses that sport perspective, perhaps, to describe the art of writing poetry. In baseball pitching, the pitcher’s art is “eccentricity” and deception:

The others [we who play catch] throw to be comprehended. He

Throws to be a moment misunderstood.

…

Not to, yet still, still to communicate

Making the batter understand too late.

The last line encapsulates concisely what happens when the batter takes a strike, or, swings and misses and yet within fractions of a second, the batter comprehends exactly what the pitcher did and the batter understands, too late.

Of course, there is no more well known line from baseball poetry than the stupendous last line from Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s, Casey at the Bat. Written in 1888, Thayer’s poem, though classified as ‘doggerel’ or poorly written comic verse, has been the inspiration for countless other poems, Disney movies, operas, novels, and even highly reputed stage-plays like Cats – not bad for so-called doggerel. The poet’s skill in the 51 lines preceding the final line is the hype and build-up of the heroic/hero, in this case “mighty” Casey who advances to the plate as the player who can save the Mudville (= any town in America) team from impending defeat. We are lead to believe passionately in the obvious result. Expectancy fairly bursts in the fans’ hearts; surely the local hero will hit a home run to carry their team to victory. And the truth is, even really good professional batters strike out more than two-thirds of their time at-bat. Part of the thrill of sport is the anticipation, the fans’ fervent hope that the batter will hit successfully, or, the other team’s support for getting batters out. Thayer could have echoed the expectation and stereotype to have Casey hit a home run and save the day. Had he done so, it is very likely the poem would never have been noticed beyond its lowly placement as a filler in the San Francisco Examiner’s 4th page. Instead, Thayer pricks the heroic balloon with

But there is no joy in Mudville – mighty Casey has struck out.

And we, in turn, are crestfallen (the latter a word of pinpoint meaning and used so frequently by one of our best friends). Of course, baseball metaphors have been utilized by many writers; one of those, the highly acclaimed Maya Angelou offered this observation:

I‘ve learned that you shouldn’t go through life with a catcher’s mitt on both hands; you need to be able to throw something back.

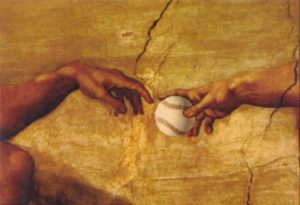

In the same vein, sometimes pictures or images, re-touched, give infinite meanings without words as does this take-off on Michelangelo’s fresco that adorns the Sistine Chapel ceiling, The Creation of Adam [from the hand of God]:

Though not at all a professional baseball fan, I remain amused at the baseball-fingertip-exchange image suggestion. And as the world reels in the midst of the COVID-19 or corona virus pandemic, the creation picture has been adapted to this one:

Often for me, it is the unusual juxtapositions of words or unorthodox descriptions that move me. Louis Jenkins’ Walking Through A Wall narrative verse is an example:

Unlike flying or astral projection, walking through walls is a totally earth-related craft, but a lot more interesting than pot making or driftwood lamps. I got started at a picnic up in Bowstring in the northern part of the state. A fellow walked through a brick wall right there in the park. I said, “Say, I want to try that.” Stone walls are best, then brick and wood. Wooden walls with fiberglass insulation and steel doors aren’t so good. They won’t hurt you. If your wall walking is done properly, both you and the wall are left intact. It is just that they aren’t pleasant somehow. The worst things are wire fences, maybe it’s the molecular structure of the alloy or just the amount of give in a fence, I don’t know, but I’ve torn my jacket and lost my hat in a lot of fences. The best approach to a wall is, first, two hands placed flat against the surface; it’s a matter of concentration and just the right pressure. You will feel the dry, cool inner wall with your fingers, then there is a moment of total darkness before you step through on the other side.

Completely unrelated to the Jenkins’ piece, the image above was taken from art-work in an actual sculpture we saw in 2012 near our apartment on a trip to Paris, France. Literally impossible? Perhaps. And, it’s the reality of the apparent walls or barriers we face in everyday life and how we handle them, at least, as I perceive Jenkins’ creative work mirrored in the sculpture. Robert Frost expressed the same sentiment re facing our dilemmas in the line, “the best way out is always through.”

In the same vein of facing tasks consistently in life, I love the Navy Seal motto:

Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.

I encountered that motto just in the last few years via binge-watching 6 seasons of the 2017-2024 TV show, Seal Team. The motto was utilized regularly in that show. It applies to so much in life and echos a similar sentiment attributed to Lewis Carroll (famed author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). . .

For me, inspirations come from other sources too. So many lines from songs strike me as profound, likely attached to the lyrical quality of the song. For example,

Billy Joel’s Piano Man…

It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday

The regular crowd shuffles in

There’s an old man sitting next to me

Makin’ love to his tonic and gin

He says, “Son, can you play me a memory

I’m not really sure how it goes

But it’s sad and it’s sweet and I knew it complete

When I wore a younger man’s clothes“

Having the old man vocalize and recall his days when wearing a younger man’s clothes is such an elegant way of expressing the man’s recollection of his past. The line is just a richer choice of words than ‘back in the day’ and completely parallel to the older man’s longing and his request of the piano player to “play me a memory.” For myself, I fondly remember wearing a younger man’s clothes in various stages of my life.

In like fashion, I conjure the mental image of the first lines of the Righteous Brothers’ 1965 hit,

Ebb Tide:

First the tide rushes in

Plants a kiss on the shore

Again, how exquisitely perfect an anthropomorphism of tidal water planting a kiss on the shore – how delicate, how profound, how accurate! And in the song itself – see the

Ebb Tide link – the tempo, melody, and vocal tone perfectly match the tidal caress.

For many years, I have thought about what it might be like to do what Mr Bojangles does in Jerry Jeff Walker’s 1968 album of the same name. The

Nitty Gritty Dirt Band re-popularized it into the version with which I am familiar (Neil Diamond’s rendition is too sort of dirgy to me, just not the rhythm appropriate to the feel of the song). Aside from its singers, the lines that intrigue me are more imagistic than musical:

I knew a man, Bojangles and he danced for you

In worn out shoes

Silver hair, a ragged shirt and baggy pants

The old soft shoe

He jumped so high

He jumped so high

Then he’d lightly touch down

As I know the story behind the lyrics, ‘Bojangles’ is the invented stage name of the most famous of all African American tap dancers, Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson. In the song, my interpretation is Mr Bojangles is a homeless man, perhaps drunk-tank incarcerated, who had travelled the US and danced at minstrel shows and honky tonks with his beloved dog for whom he is still grieving 20 year’s after the canine’s death. Mr Bojangles could click his heels, laugh, jump so high, and dance. But what endears him to me is the imagery of him jumping so high, then, deftly, cat-like “he’d lightly touch down.” I don’t know that lightness in dance (I can barely dance without embarrassing myself), that agility – such a soft and delicate manoeuver. Unabashed about his ill-fitting clothing, his worn out shoes, his appearance, his grief, his laughter – and he can lightly touch down, a phrase we now reserve for smooth aircraft landings, at least in pre-COVID-19 days when flying was common.

The image above reminds me of the first time I saw Michael Jackson, that paragon and flawed genius of music and dance, perform his

Billy Jean. It wasn’t his moon walk that struck me, rather it was his agility and the speed with which he so deftly snapped his leg and just his moves so reminiscent of Gene Kelly’s adroitness in

Singing in the Rain. And, of course, there is no softer, more poignant image of delicacy and grace than Carl Sandburg’s

Fog and the feline juxtaposition with an urban landscape:

The fog comes

on little cat feet.

It sits looking

over harbor and city

on silent haunches

and then moves on.

My favourite novel of all time, Heart of Darkness (1902, by Joseph Conrad), I first encountered in grade 11. For some reason, I was quite flummoxed that we had to read such a strange-titled novel whose author was unknown to me and who the hell wanted to read about a heart that was dark. But like the novel-narrator, Marlow who became mesmerized by the serpentine Congo River and concluded – now famously – “the snake had charmed me,” the story, to say the least, captivated me. Conservatively, I have read the book a dozen times since the age of 15. My dog-eared, dilapidated (from recurrent use) hard cover version opened to any page reveals my zeal for the novel; my red, ballpoint-pen underlining of clearly important lines and words is ubiquitous, as are the penned-in marginal notes. What still captures me are the layers and levels of meaning from the literal journey into the Belgian Congo to find Mr Kurtz all the way to the lifelong expedition we all have to the very centre of our souls. The movie adaptation, Apocalypse Now was interesting and entertaining for me; Robert Duvall’s brilliantly deliverd, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning” echoes cinematically Conrad’s character Mr Kurtz dying words, “the horror the horror.” These 4 words are delivered by Marlon Brando in the movie but it is Duvall’s line that conveys more of the horror intended [an admitted word-tribute to Kurtz’s “Intended” in the novel], I think, by Joseph Conrad.

My second son, Joe was named after the novelist, so great was and is my respect for Mr Conrad, let alone for who my son has become. Often so many words and images of the novel come back to me – Marlow sitting against the ship’s mast, the knitters of black wool, the 3 stations, and so many more. However, unlike most of the expressions I recall throughout this blog, it was my consternation over one passage that engulfed me:

It’s weird how out of touch with truth women are. They live in their own world, and there has never been anything like it, and never can be. It’s too beautiful to be real, and if they tried to make it happen it would fall apart before the first sunset. Some well-known fact that we men have been living with since the beginning of time would come and knock the whole thing over.

Charles Marlow visits with his aunt before going by steamer to the Congo. These lines are part of his self-reflection about their conversation as he leaves her. To me, there was an audacity and bravado and judgement about “it’s weird [queer in the original version] how out of touch with truth women really are.” I understood and understand Polish author, Conrad and his Victorian world, his views about colonialism, certainly his feelings on racism. But why would women be out of touch with truth? Years ago, after coming to believe how much truth/s is/are relative, how seemingly opposite perspectives about someone or some situation can both be ‘true,’ I decided what Conrad should have said, or, might have said now is, ‘it’s weird how out of touch with men’s truth women are.” Nothing else troubled me about the diction, the choice of words, the images in that book…but that line vexed me. Strange what impact words can have and what different meanings we can derive from them.

I think too of lines that explode with meaning. Hemingway’s profound, thematic one-liner from The Old Man and the Sea:

Fishing kills me exactly as it keeps me alive.

Subsitute any of our passions or obsessions for the word ‘fishing’ to test Hemingway’s assertion. In perhaps one of the finest books on cultural meanings ever written, Beyond a Boundary, C.L.R. James declared:

What do they know of cricket who only cricket know.

In such a world of specialization, James so gently queries human tendency not to see our world in and from all perspectives. In my academic career, so many erudite books hammered home meanings. In Postman and Weingartner’s profound criticism of and kind of eulogy to outdated pedagogy, Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1971), they asked one very potent question, “What is worth knowing?” That question became a barometer and map for me in deciding what to teach students and how I taught them. As a trained historian, I read, re-read, and read again, Robert F. Berknofer Jr’s A Behavioral Approach to Historical Analysis (1969) and I fervently I came to believe in that author’s claim that history is historiography. In short, no historian can possibly tell about events exactly as they happened in the past. Instead, historians interpret from the past (what most people call history) or fragments from that past in efforts to help humans understand their past. History then depends on the questions historians ask of the past and the methods they use to describe and assess that past. Controversial at the time, there remain many historians who believe they can tell or interpret the past exactly as it happened. I never could.

A professorial colleque of mine, a person with whom I had so many difficulties during my career and yet a man I admired greatly for his brilliance had a wonderful expression about rules. He said,

Rules were made for the guidance of wise people and the blind obedience of fools.

To me, it remains a solid expression of personal responsibility, our freedoms, and our decision-making capacities. In the latter regard, I remember another colleague whose succinct, often-rendered advice to anyone, it seemed, was ‘

not to decide is to decide.’ Similes, comparisons using ‘like’ or ‘as,’ reconfigure, sometimes with exaggeration, my way of interpreting the world. Among many similes, two come to mind, both using the same noun for the analogy. When under stress or overwhelmed, some say i

t’s like trying to drink from a fire hose. A former dean of mine, in describing a person’s high aerobic capacity (the ability to take in and utilize oxygen when exercising) said, s/he

has an aorta (the main, large artery leaving the heart muscle)

like a fire hose. Canadian author W.P. Kinsella was a master of the simile; my favourite one is, “

the moon revealed itself like a magician peeling his silk handkerchief off an orange” (

Shoeles Joe novel). Over my life, I have become a great believer in the huge power and significance of one, 3-letter word in the English language –

and.

And is so much more inclusive than either/or or but and our likely unintended tendencies to be so sure about one way of thinking or perceiving. The word ‘and’ connects in communication, takes me out of chocolate or vanilla choices and into the world of Baskin & Robbins’ 31 varieties, Häagen-Dazs, Halo – not literally but emblematically – and the myriad judgments and important decisions we must make on a daily basis.

There are also ways in which words can be represented without actually being said. For example, in John B. Lee’s wonderful book, The Hockey Player Sonnets (1991) featuring 73 pages of poems inspired by the game of hockey…

…the poet, Lee takes us into the male locker room and a humorous rendition and stereotype of the ‘fuck’ language that permeates male locker room speech in the poem that reflects the collection’s title. Instead of using the actual word, fuck, Lee substitutes (e.d.) for every time the players use the F-shot word in any of its grammatical forms. The result is a humorous and sardonic rendering of predictable locker room swearing without ever using the word fuck and yet every time ‘(e.d.)’ is used we know exactly what’s missing through all 30 lines of the poem:

What about them Leafs, eh! (expletive deleted)

couldn’t score an (e.d) goal

if they propped the (e.d.s) up

in front of the (e.d.) net

Marion Woodman, famed Jungian scholar, speaker, humanitarian (and life-partner of Ross Woodman, noted above), among her plethora of books, authored The Pregnant Virgin: A Process of Psychological Transformation. Among its many, many truisms, one stands out to me, paraphrased below:

It won’t work if you stand in front of a flower and yell, Bloom!

I cannot imagine the number of times figuratively I have stood in front of life-flowers yelling “Bloom!” It is a lesson that the beloved great Dane cartoon character, Marmaduke (Bob Anderson, creator) underscores in a 2022 caricature:

There is a humility and reality to understanding that flower-yelling-folly. Somewhat in parallel, one of my dearest friends has a wonderful proclamation about coincidences. She says,

Coincidences are God’s way of remaining anonymous.

I love Oriah Mountain Dreamer’s, The Invitation, especially its opening lines:

It doesn’t interest me what you do for a living.

I want to know what you ache for

and if you dare to dream of meeting your heart’s longing.

It doesn’t interest me how old you are.

I want to know if you will risk looking like a fool

for love

for your dream

for the adventure of being alive.

To think of being in life and alive by invitation, not by accident stirs my heart. A close second to my Heart of Darkness book fondness is my enduring respect for A. A. Milne’s books on Winnie-the-Pooh and Milne’s wondrously named array of characters and characterizations – Piglet, Kanga, Roo, Tigger, Rabbit, Eeyore, Christopher Robin – and their machinations in the Hundred Acre Wood . Just the image of Pooh makes me smile and so many things I could quote from Pooh’s adventures. I leave this blog with one image and line from those books as I tumble home, always, and in a variety of ways, to words that lift me up, inspire meaning in my life, and carry my imagination to what is possible:

[How inspirational to me is it witnessing Pooh paddling a a water c/raft and he is easily forgiven for not sitting in its tumblehome, or, is he?]