Anatomically. . .

“What a piece of work is a [hu]man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel…William Shakespeare, Hamlet Act 2, scene ii

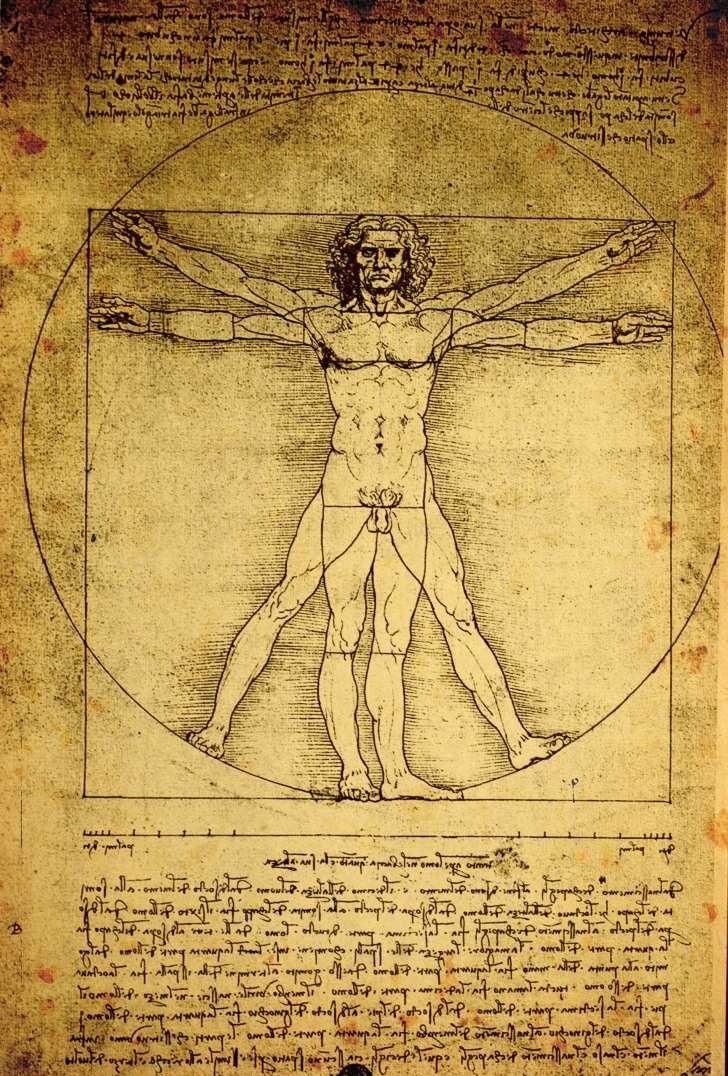

Popliteal fossa, the olecranon process, and the extensor digiti minimi are just some of the hundreds of anatomical terms that have imprinted on my mind for half a century. The human body has been magnetic to me all my life. By that I mean, I have always enjoyed my body and been stunned by its performance capacities; measuring myself against others in sport; marvelling at the incredible capabilities of bodies in exercise, athletics, arts, music, labour; and just generally observing bodies in motion – “in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel” indeed! Most of what I know about the human body comes from my knowledge of how muscles move us. In second year university, a full-year, gross Anatomy course, using cadavers, provided me with a precise language for understanding the body’s structures and functions. In this blog, I want to ruminate about anatomy, its nuances, and its meaning to me – and to society and culture in general – across my lifespan and across time. A pictorial example from one of the world’s greatest artists seems like a corporeal place to start…

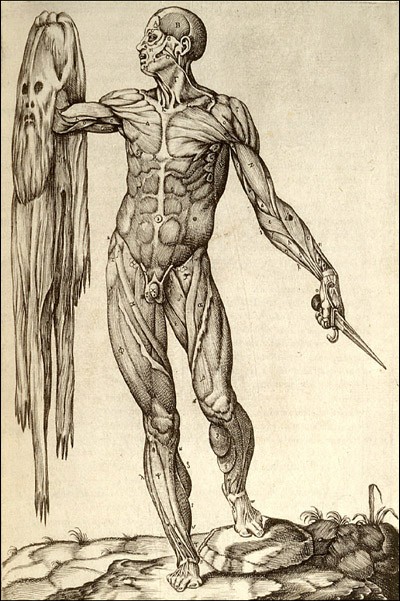

Da Vinci’s fame aside, sixteenth century Flemish physician, Andreas Vesalius is recognized as the founder of modern human anatomy. His renderings of the body, sometimes with distorted proportions, always seem eerie to me, as though he were trying to breathe an eccentric life into skeletal and muscular figures. Nevertheless, his, da Vinci’s, and many other early anatomists made incredible and indelible contributions to understanding the structures and functions of the human body. Today, medicine, physical therapy, physiology, and a host of other disciplines and professions rely upon these anatomical pioneers along with a more modern intricate, sophisticated corpus of ways and means to understand the body’s systems and structures, right down to the cellular level.

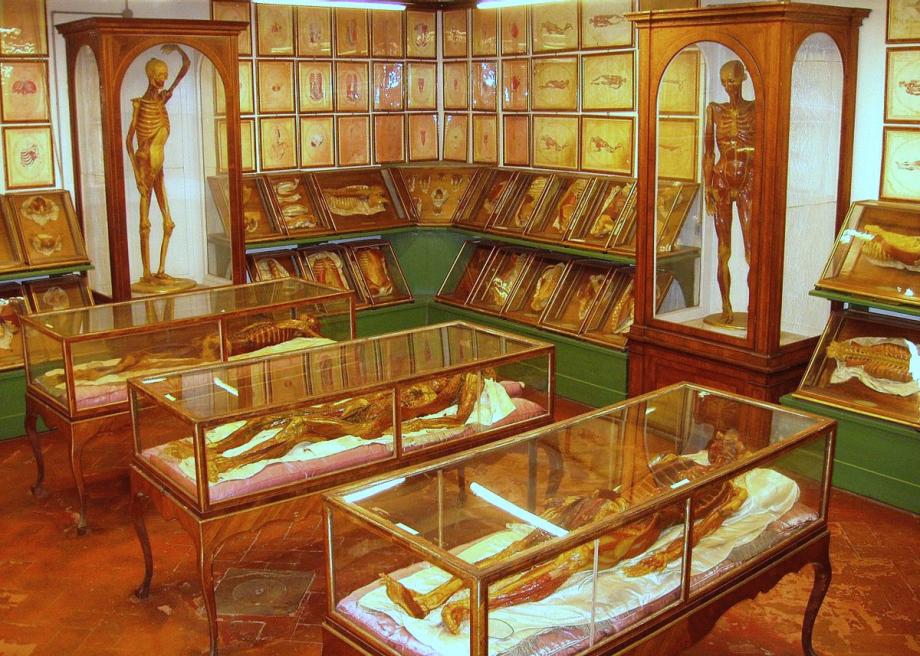

Latin, as I have noted elsewhere in my blogs, was a fundamental building block in my learning of so many subjects not the least of which was anatomy; its terms and body-descriptions made so much sense – the irony of a so-called ‘dead’ language in using dead bodies, cadavers to to study anatomy was not lost on me. Learning gross anatomy by probing and dissecting cadavers is disquieting, at least at first. Science and education in general are indebted monumentally to the individuals who donate their bodies for study; Anatomy professors instill a profound and reverential respect among students who are privileged to work with these human bodies. Many universities use plastic models and/or sophisticated 3D, often virtual technologies to teach the subject; however, viewing and touching actual human tissue is the recognized, ideal way to learn about the body, with one possible exception – the La Specola Museum collection of anatomical wax models:

The Specola collection, often referred to as “the past in wax” was opened to the public in 1775. As one of the narrators in this Specola video opines, they are pieces of “immortal beauty, immortal anatomy.” Created for educational purposes, the idea behind the models was to allow the public to view and learn about the body as well as students enrolled in various science and medical programs. The level of intricacy and detail, even by modern standards, is incredible, so much so that Standford University has created a 3-dimensional learning platform using the various models (noted in the video cited at the beginning of this paragraph). To make the models, cadavers were dissected and made into clay forms and then into plaster moulds which, in turn, were filled with wax to render the final models. The resultant 1400 pieces of art, featuring every part of the human body, are displayed in some 580 showcases throughout the rooms of the museum.

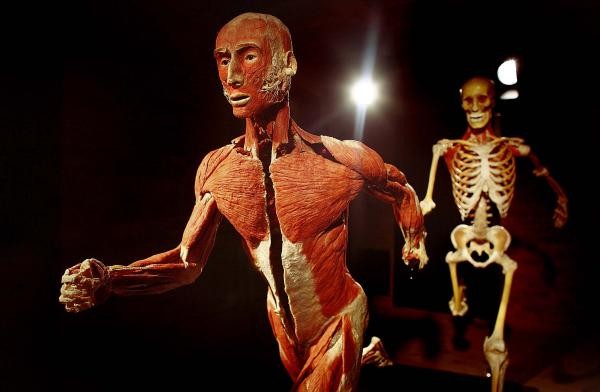

My point in this excursion into the Specola collection is to underscore how much human anatomy can impact us. In our era, the Body Worlds exhibitions are renowned internationally for “…insights into the highly complex structures of the human body and shows what connects us, keeps us upright and in motion, and what makes us laugh and love.” Plastinated (actual bodies that have their water and fat removed and replaced with special plastics), anatomical poses of body-specimens in everyday life take us “under the skin” of humans to mirror facets of humanity that give meaning to our existence: happiness & unhappiness; excess & moderation; gluttony & restraint; chance & destiny. And there are other body exhibitions, traveling or museum renderings of the anatomical wonders of the human body. For more visuals, visit this video describing the Body Works exhibition in some detail. It humours and intrigues me to see the creativity applied to using anatomical representations of humans in daily life from this particular exhibition.

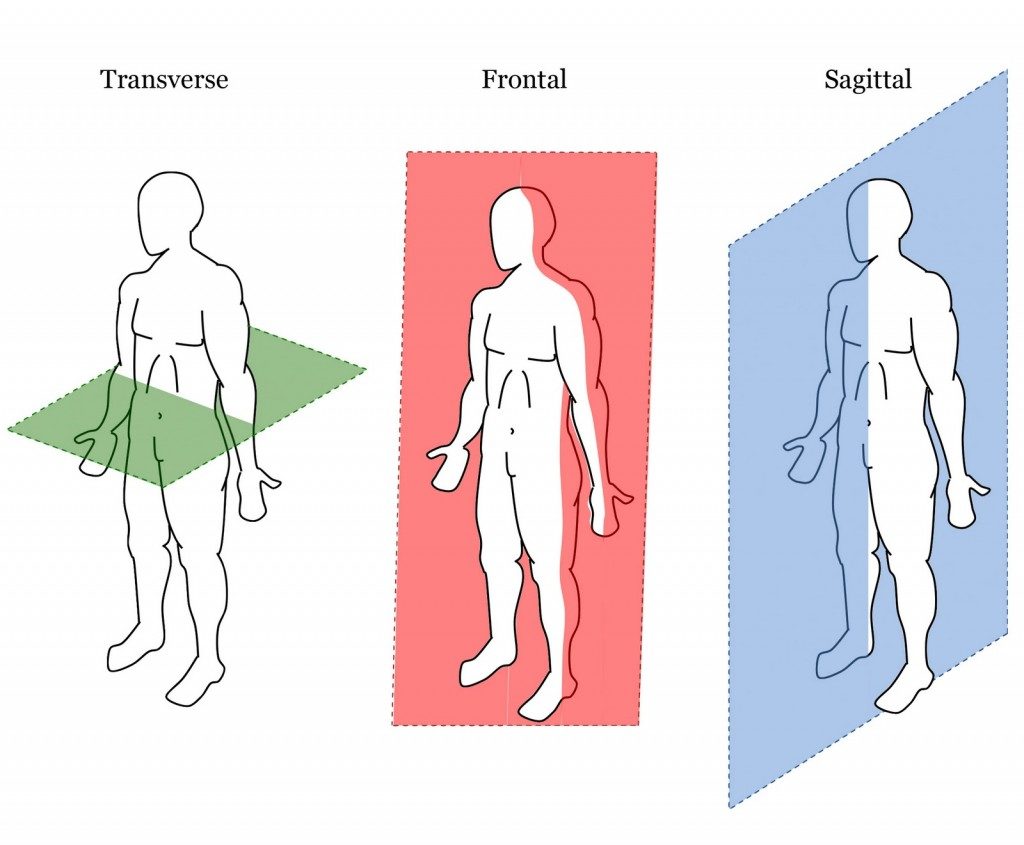

What I learned at a macro level about gross anatomy were the muscular system, the bony skeleton, neural stimulation, ligament structures, and circulatory mechanisms. Of greatest impact on me, was acquiring an understanding of origins and insertions of muscles and tendons and concomitantly how specific muscles acted on bones and joints. It was, for me, akin to putting an envisioned jigsaw puzzle together in that anatomical terms suited human movements with such precision, beginning with the perfect, to me, Latin phraseology. By convention, every anatomical description assumes the body is in the “anatomical position” – da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man sketch depicted at the start of this blog, reflects, for the most part, that position; – body supine, legs straight, arms at the sides, palms up, thumbs out. From the anatomical position, all movement occurs along 3 planes (see the image below):

Thus, there is standardization to describing any human movement according to the plane or cross-section in which the body or body segment moves, together with what’s called the axis of rotation of particular body parts. For example, forearm flexion and extension occur along the sagittal plane; abduction takes a body part, such as the leg away from the body in the frontal plane while adduction (= ‘add’ to) describes movement toward the body in the same plane. And not all movements can be described in simple terms; a series of summersaults, for example, is a fairly complex network of body movements. We are a complicated set of levers when it comes to thinking of different functions of the body and/or its parts.

What I visualize often is that all movement, stripped of imagining the body literally, occurs in arcs or a series of arcs. Where and how each arc intersects with the next arc, when done efficiently, makes for fluid movements; that is, the timing of arc intersection qualifies movement. For example, walking is really a series of near accidents, narrowly avoided. When upright, legs together and we lean slightly forward while moving one leg out to step, if that forward foot lands and we maintain our balance, we take a walking-step (and repeat with the other leg to start walking); should we lean slightly forward without putting one leg out and continue to lean, we will eventually fall. Children, learning to walk then, actually learn how to prevent falling by sticking alternate legs out as they move forward, each time, narrowly avoiding falling accidents. And arcs happen not just in human movement but also in our speech patterms, the latter in terms of how and when we use words and sentences to communicate. For example, in telling a joke, the manner of delivery and especially the timing of the punch line can be thought of one verbal arc intersecting another arc at just the right moment. Thus, just as we try orally to communicate effectively, so too do our bodies communicate, relatively effectively, depending on the stage of learning, in movement series. Playing a game of catch is a form of communication wherein two people want each other to catch the ball; by contrast, a professional hardball pitcher wants to be misunderstood, to make the batter understand too late.

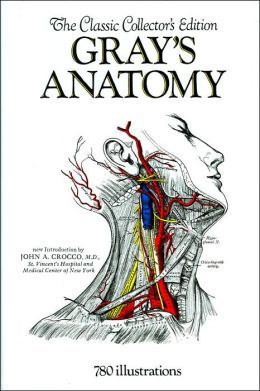

My fascination with how we move might be obvious by now. The exactitude of anatomical language is profoundly accurate and accurately profound. Lateral describes body parts closer to the outside of the body; medial, closer to the mid-line; anterior means in front, posterior, to the rear; superior above, inferior below. Thus, in the anatomical position, the left knee cap (the patella) is medial to the right knee, inferior to the hips, and anterior to the spine; describing the body and/or its movements, using anatomical conventions, is an exact science, captured, as described above in the Specola Collection, Body Works, and detailed in anatomy primers like Gray’s Anatomy…

The Gray’s classic was cleverly adapted using just one different letter to create the title of the TV medical drama, Grey’s Anatomy, as of today’s date, in its 15th season. Learning elements of anatomical language for me, came from university lectures and labs buttressed by Basmajian’s textbook, Primary Anatomy, itself a bit of a classic guide to studying the area. Ironically, art and science were married and mailed to me as a book-of-the-month club subscriber. Early in my academic career, I ordered Canadian author, Robertson Davies’ now-acclaimed novel, Rebel Angels. Unbeknownst to me, the Club sent a complimentary, soft cover copy of Gray’s Anatomy, all 1500+ pages as a bonus for buying the Davies’ work of fiction. As a lover of literature and enraptured by anatomy in all its aspects, I danced inside myself, metaphorically jumping so high and lightly touching down, Mr Bojangles-like, when I opened the book package and comprehended its contents. And at Pentacostal Bible school, in the summer after grade 6, living in Exeter, I was taught the spiritual hymn/song, Dem Bones; both the rhythm and the visualized (at the time) connections of the body’s bones, from foot to head bone and back to toe bone drew me, very likely to my first articulation of the body’s framework. In passing, I recall making a butterfly-shaped corner knick-knack shelf out of wood at that summer school; I see that butterfly repeated in our small business, The Monarch System Inc. The song, now called Dry Bones has been popularized as a children’s song with all manner of visual effects and dances such as the one in this video.

Perhaps as much as the language and depictions and logic of anatomy for me, the other equally attractive lure to human anatomy was and is simply the sheer sounds of anatomical terms. Few know this about me but I have a trait called synaesthesia, a neurological condition that results in a joining or merging of senses that aren’t normally connected. For example, some folks with synaesthesia “see” sounds. In my case, I cannot ever hear a day of the week or think of the days of the week without seeing colours, in my mind’s eye. Saturday is red, Friday brown, Wednesday purple, Thursday azure-blue. While my synaesthesia around days of the week has been lifelong, with anatomy, I memorized/learned it so thoroughly that I see specific muscle groups and am fully aware of their actions as soon as I hear a muscle named or if I see an athlete or my wife cooking in the kitchen, I find myself analyzing the movements to envision different groups of muscles being ennervated. When I use a screwdriver to tighten a screw, I can feel and see both my biceps and brachioradialis muscles whipping my wrist (the distal end of the radius bone rolling over my ulna). But, it’s the sound of muscle names, like the brachioradialus that draws me – I hear the name, see the muscle.

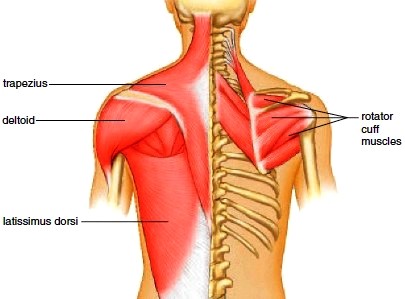

The deltoid – literally meaning triangular – muscle cups the shoulder, gives it its shape and is the major muscle in moving one of the most mobile joints in the human body through a full range of motion, lifting the humerus or upper arm bone out in front of the body, to the side, as well as posterior to the torso, each and all movements dictated by our choice. Akin to its actions, the name deltoid is smooth and is perfectly descriptive of its shape. Structure preceds function, always. Freestyle swimmers have particularly well developed deltoids along with the counterpart muscle, the fan-shaped ‘lats’ or latissimus dorsi, literally, the broadest muscle of the back. the lats clothe most of the ribs of the mid-back, and dovetail toward the armpit to insert on the humerus to permit a variety of shoulder movements including extensions and internal arm rotations. Well developed lats give the broad, kind of upside-down, triangular appearance of the upper back. And just so many other exquisitely named muscle groups – the trapezius muscle of the upper back and neck; the biceps brachii that get false credit for ‘bicep curls’ and well developend upper arms when we flex our elbows – it is the muscle deep to the biceps, the brachialis that really does the work of elbow flexion against resistance; finally, the rotator cuff muscles that arise across the posterior aspect of the shoulder blade and insert on the posterior part of the head of the humerus, in part to keep the latter bone in its socket, and functionally to help raise and rotate the arm.

A great deal that I’ve learned about anatomical functions has come through my experiences with sport/exercise injuries. For example, most recently, I completely severed one of my right, rotator cuff muscles and had to have arthroscopic surgery – the only surgery I had ever had up to that point in my life – to sew and staple the severed tendon back in place. As a racket sport player, I have relied on my rotator cuff muscles all my life; throwing a ball now requires great care not to do so ballistically and re-tear the repair. For two months post-op, I learned to do everything left-handed, having to think carefully about how to do even simple movements like eating. As a marathon runner, I was plagued by plantar fasciitis, a debilitating injury to the fascia or delicate membrane-tissue that surrounds all muscles and organs of the body, in this case, the tendon on that helps form and support the arch on the bottom of the foot. Once soft tissue is inflamed, it requires rest and light stretching to help the scar tissue form and healing to take place. However, with plantar fasciitis, it is very difficult to stay off the foot just because of the need to walk; sleeping at night seemed to be just enough time for some scar tissue to form on the fascia such that when getting up each morning, the tissue is re-injured. Thus, I learned about orthotics and special neoprene insoles to maintain the integrity of the arches of the feet.

My lifelong nemesis anatomically has been my hamstring muscles, the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris that make up the hamstring muscle group so important in knee flexion and hip extension. All muscles work in opposing pairs, agonists are the major group doing the work -the prime movers, while the antagonists provide stability and support to permit the agonists to work efficiently. In my case, I overuse my quadriceps, the four muscles that make up the front thigh; running, in reality, is a quadriceps’ exercise, repeated quad contractions propel us forward. Thus, my hamstrings over the years have become accustomed to a very narrow range of motion and are extremely tight. It has meant being constantly devoted to doing hamstring and lower back stretches. In the same vein – a figurative anatomical expression – yoga, pilates, and rehabilitation exercises have meant that I am able to recuperate and maintain my passion for sport and physical activity.

And so I return to the proportion and architecture of Leonarco da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. There is just such beauty to the human form. and its capacities, structures, and functions. And it has always struck me what a resilient entity is the body and at the same time, what a delicate instrument we are. Some religions implicitly disparage the body somehow seeing humans as essentially a soul, for mysterious, accidental reasons imprisoned in a body. To me, the body is our mortal engine, warranting respect, care, compassion, and reverence. In form and moving, we are, as Shakespeare noted, so very “express and admirable.” Often each day, I tumble home to the lessons I have learned from anatomy, my own body, and the capacities and exquisiteness of the human body.

In recognition of and tribute to him, I want to post two pictures of Dr Glynn Leyshon, my Anatomy professor, colleague, friend, and superb teacher…